Fig. 35.1

Mitral valve (long arrow) and aortic valve (short arrow) in view. Note the minimal leaflet excursion of the aortic valve cusps

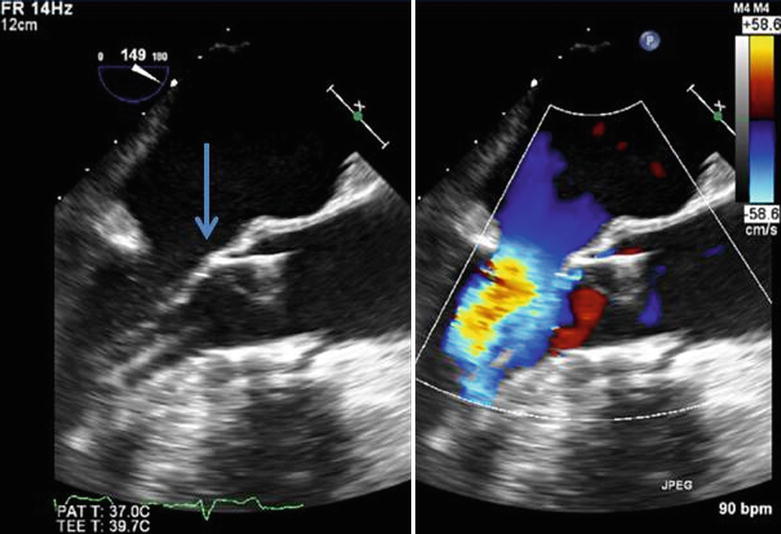

Fig. 35.2

Moderate aortic regurgitation prior to TAVR

Fig. 35.3

3D TEE of the aortic valve. The extent of calcium deposition can be appreciated from this short axis image. The echolucent areas along the base of the cusp commissures are dropout artifact of the image and do not represent true openings (arrows)

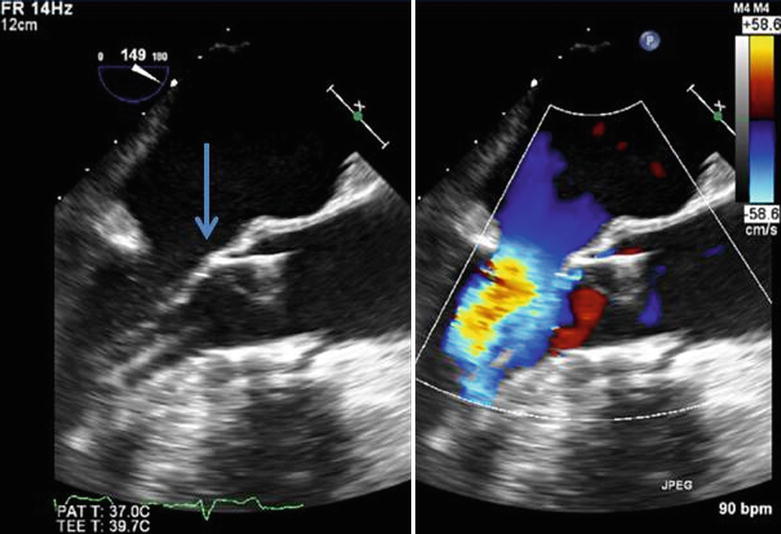

Fig. 35.4

Severe transvalvular aortic regurgitation immediately post TAVR

Fig. 35.5

Arrow shows trace paravalvular aortic regurgitation (left) and severe transvalvular aortic regurgitation (right)

Fig. 35.6

Aortic flow reversal along descending aorta, consistent with severe aortic regurgitation (arrow denotes duration of diastolic flow reversal)

Fig. 35.7

Decision is made to recross the deployed transcatheter valve and place a second transcatheter valve within the first (valve-in-valve). Arrows show the guide wire (short arrow) and bioprosthetic leaflet (long arrow) during diastole

Fig. 35.8

A second bioprosthetic aortic valve has been deployed and there is no longer any transvalvular aortic regurgitation, with trace paravalvular aortic regurgitation (arrow)

Fig. 35.9

Fluoroscopy of transcatheter valve-in-valve, immediately prior to deployment (left) and post deployment (right)

Case 2: Mitral Regurgitation

If the valve is deployed too high in the aortic root, it can lead to coronary ostia obstruction or upward valve embolization, but if it is deployed too low in the LVOT, it can lead to downward valve embolization or restriction of the anterior mitral leaflet with resultant mitral regurgitation (MR). One of the major benefits of TEE over other imaging modalities for TAVR is that it can help the operator discern the distance of the bioprosthetic valve to neighboring intracardiac structures in real-time, including the mitral valve. It is unclear what high-risk features can lead to anterior mitral leaflet restriction or how to manage it as there are is a paucity of published cases, but as will become evident by the case that follows, it is a potential complication of TAVR. This is a case of a bioprosthetic aortic valve that was deployed too low in the LVOT, leading to restriction of the anterior mitral leaflet and the development of mitral regurgitation.

Case 2: P.I

An 88-year-old male presented with history of aortic valve stenosis, coronary artery disease status post CABG, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, cerebrovascular disease, and diabetes. TTE showed LVEF 72 %, a mean AV gradient of 48 mmHg, and an AVA 0.8 cm2.

Patient Underwent

1.

Balloon aortic valvuloplasty with a Z-MED 22 × 40 mm balloon

2.

Transcatheter aortic valve implantation using a 26-mm Edwards Sapien valve via femoral approach (Figs. 35.10, 35.11, 35.12, 35.13, and 35.14)

Fig. 35.10

Severe aortic stenosis with no evidence of mitral regurgitation

Fig. 35.11

Moderate mitral regurgitation (arrow) as a result of a low-lying bioprosthetic aortic valve restricting the movement of the anterior mitral leaflet

Fig. 35.12

Arrow shows where the anterior mitral leaflet comes into contact with the distal portion of the struts on the bioprosthetic aortic valve, restricting its motion

Fig. 35.13

A different patient with severe mitral regurgitation as a result of transient left ventricular dysfunction (stunning) after rapid ventricular pacing required for TAVR deployment

Fig. 35.14

Patient in Fig. 35.13 showing a marked decrease in mitral regurgitation after recovery of left ventricular function

Case 3: Aortic Root Hematoma

An extremely rare but serious complication of TAVR is aortic annulus rupture. This complication usually occurs during balloon valvuloplasty of the aortic valve or during valve deployment, with an incidence of aortic annular rupture of approximately 0.50 % [3, 4]. High-risk features that can predispose patients to aortic annular rupture include a heavily calcified aortic annulus or a narrow sinotubular junction. Correctly sizing these structures is of critical importance in limiting this complication. Efforts must be made to limit overdilating a small and calcified aortic annulus or sinotubular junction.

The consequences of aortic annulus rupture can be devastating, including death. It is possible to manage some of these patients conservatively with blood pressure control and reversing anticoagulation, but there are circumstances when they may need cardiopulmonary bypass in preparation for cardiothoracic surgical repair. This is a case of aortic root hematoma that was quickly noticed by TEE. The operator was able to limit its extent, preventing annular rupture and tamponade by aggressively controlling the patient’s blood pressure and reversing anticoagulation.

Case 3: S.C

An 83-year-old female presented with history of severe aortic valve stenosis, coronary artery disease status post CABG, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, atrial fibrillation, and severe mitral regurgitation. TTE showed LVEF 50 %, mean AV gradient of 51 mmHg, AVA 0.5 cm2, severe mitral regurgitation, and moderate-to-severe tricuspid regurgitation.

Patient Underwent

1.

Balloon aortic valvuloplasty using 18 × 50 mm Z-MED II balloon

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree