Clinical Presentation

The patient is a 24-year-old female who presents acutely with low back pain and urinary incontinence. She has seen several physicians and has had several emergency room visits in the last 6 months for escalating back and leg pain. She had an imaging study that demonstrated a small focal disc herniation at L3-4. She has been taking over-the-counter pain medications ever since. This afternoon she took a nap and when she woke up she felt that her feet were swollen. She cannot move her toes. When she went to the bathroom, she lost control of her bladder. She feels numb from the waist down. Her legs show a sensory deficit at the lower outer mid leg in approximately the L5 distribution. She has intact hip flexion and knee extension. She is unable to flex or extend her ankles. She has intact distal pulses. She has brisk symmetric patellar reflexes. She has no Achilles reflex and a Babinski reflex cannot be obtained on either side.

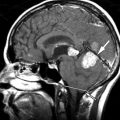

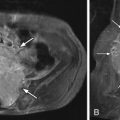

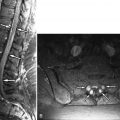

Imaging Presentation

Sagittal and axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance (MR) images reveal a very large soft tissue mass extending posteriorly to occupy the entire spinal canal at the level of the L3-4 disc. This mass appears to be connected to the L3-4 disc and has similar signal intensity to disc material. The findings are compatible with a large disc herniation. On the axial T2-weighted MR image, there is obliteration of the normal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)–containing thecal sac from the disc herniation, which incorrectly makes this image look T1-weighted ( Fig. 14-1 ) .

Discussion

Cauda equina syndrome (CES) has been defined as low back pain, unilateral or usually bilateral sciatica, saddle sensory disturbances, bladder and bowel dysfunction, and variable lower extremity motor and sensory loss including paraplegia. The clinical diagnosis of CES should not be made unless there is bladder, bowel, or sexual function abnormality.

The cauda equina is formed by the nerve roots caudal to the level of the conus medullaris. The cauda equina syndrome can result from any lesion that compresses the cauda equina and causes a dysfunction of multiple lumbar and sacral nerve roots. The most common etiology of CES is a large central lumbar disc herniation at the L4-5 or L5-S1 level. Patients may be predisposed to CES if they have a congenitally narrow spinal canal or an acquired spinal stenosis. Some other etiologies of cauda equina syndrome include a traumatic injury, neoplasm, spinal anesthesia, spinal epidural hematoma, abscess, late stage ankylosing spondylitis, inferior vena cava thrombosis, and iatrogenic causes such as chiropractic manipulation or postoperative complications. There is no gender or race predilection for CES; however, atraumatic CES is most often seen in adults secondary to surgical morbidity, disc degeneration, neoplasm, and abscess. If a young adult presents with CES, a large midline disc herniation should be suspected.

Patients with CES often present with bilateral leg symptoms that include sciatica, weakness, sensory changes, and gait disturbances. The symptoms can vary greatly: from mild paresis to complete paralysis, paresthesia to complete anesthesia, difficulty walking to inability to ambulate. There can be minimal to no back pain. Bowel or bladder incontinence can present alone or in combination. The urinary incontinence of CES is due to overflow from an asensate bladder with high volumes. Most clinicians divide CES into two categories: CES with established urinary retention or incomplete CES in which there is reduced urinary sensation, loss of desire to void, or a poor stream, but no established retention or overflow. It is important to know whether the patient is incontinent to urine at the time of presentation because this has a very poor prognosis.

The diagnosis of CES begins with a good history and the finding of any of the classic symptoms of CES. A physical examination can narrow the differential. With CES, the patient’s reflexes may be diminished or absent. Hyperactive reflexes may signify a lesion above the cauda. Likewise, a positive Babinski sign should lead one away from the diagnosis of CES and toward an upper motor neuron lesion. The urinary bladder can be catheterized to evaluate for a significant urine volume with little to no urge to void.

Discussion

Cauda equina syndrome (CES) has been defined as low back pain, unilateral or usually bilateral sciatica, saddle sensory disturbances, bladder and bowel dysfunction, and variable lower extremity motor and sensory loss including paraplegia. The clinical diagnosis of CES should not be made unless there is bladder, bowel, or sexual function abnormality.

The cauda equina is formed by the nerve roots caudal to the level of the conus medullaris. The cauda equina syndrome can result from any lesion that compresses the cauda equina and causes a dysfunction of multiple lumbar and sacral nerve roots. The most common etiology of CES is a large central lumbar disc herniation at the L4-5 or L5-S1 level. Patients may be predisposed to CES if they have a congenitally narrow spinal canal or an acquired spinal stenosis. Some other etiologies of cauda equina syndrome include a traumatic injury, neoplasm, spinal anesthesia, spinal epidural hematoma, abscess, late stage ankylosing spondylitis, inferior vena cava thrombosis, and iatrogenic causes such as chiropractic manipulation or postoperative complications. There is no gender or race predilection for CES; however, atraumatic CES is most often seen in adults secondary to surgical morbidity, disc degeneration, neoplasm, and abscess. If a young adult presents with CES, a large midline disc herniation should be suspected.

Patients with CES often present with bilateral leg symptoms that include sciatica, weakness, sensory changes, and gait disturbances. The symptoms can vary greatly: from mild paresis to complete paralysis, paresthesia to complete anesthesia, difficulty walking to inability to ambulate. There can be minimal to no back pain. Bowel or bladder incontinence can present alone or in combination. The urinary incontinence of CES is due to overflow from an asensate bladder with high volumes. Most clinicians divide CES into two categories: CES with established urinary retention or incomplete CES in which there is reduced urinary sensation, loss of desire to void, or a poor stream, but no established retention or overflow. It is important to know whether the patient is incontinent to urine at the time of presentation because this has a very poor prognosis.

The diagnosis of CES begins with a good history and the finding of any of the classic symptoms of CES. A physical examination can narrow the differential. With CES, the patient’s reflexes may be diminished or absent. Hyperactive reflexes may signify a lesion above the cauda. Likewise, a positive Babinski sign should lead one away from the diagnosis of CES and toward an upper motor neuron lesion. The urinary bladder can be catheterized to evaluate for a significant urine volume with little to no urge to void.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree