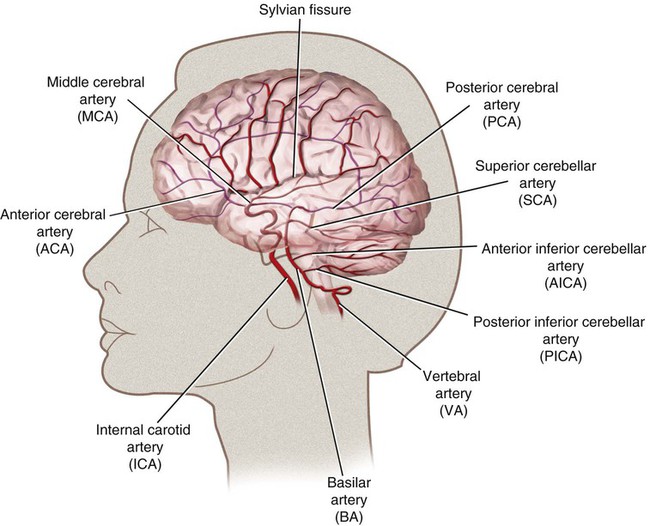

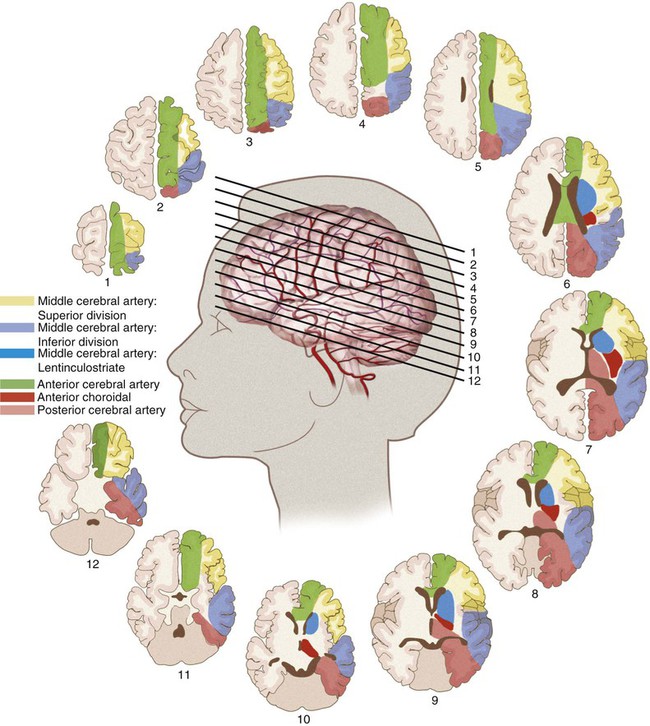

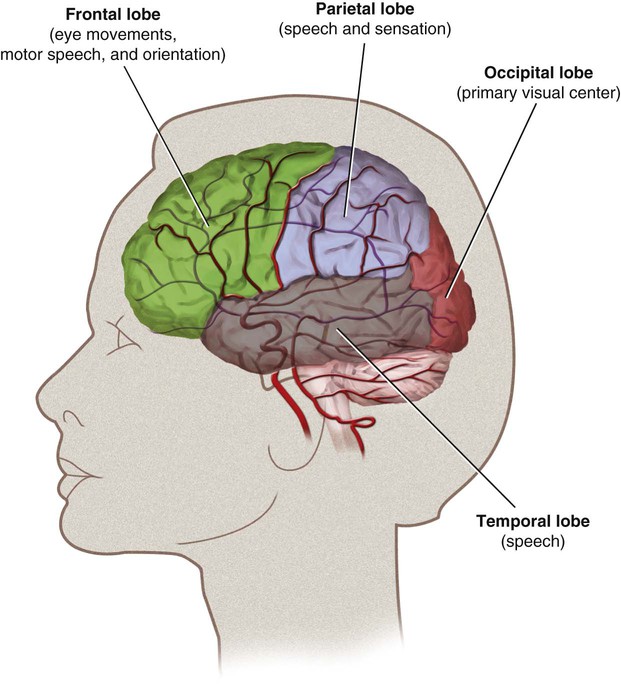

The literature reports various rates of complications from 0% to 28%1; however, the technology for cerebral angiography has gone through extensive improvement over the course of this time. Dion et al. found that in patients undergoing cerebral angiography for any cause, within the first 24 hours there was a 1.3% neurologic complication rate.2 In the ischemic stroke/transient ischemic attack population there was a 4% neurologic complication rate, with 1% of those deficits being permanent.1 Additionally, 23% of patients undergoing cerebral angiography were found to have silent infarctions on diffusion weighted imaging.3 This is important when considering the overall disease burden a patient will accumulate. The anterior circulation is derived from the internal carotid arteries. The primary branches are the anterior cerebral artery (ACA) and the middle cerebral artery (MCA). The ACA supplies most of the anterior medial surface of the brain’s cortex. The MCA divides into three major branches. The superior division supplies the frontal lobe cortex above the sylvian fissure and the perirolandic cortex. The MCA inferior division supplies the temporal and parietal lobe cortex behind the sylvian fissure. The MCA territory supplies most of the cortex on the dorsolateral convexity of the brain (Fig. 90-1). The posterior circulation is derived from the vertebral arteries, which merge into the basilar artery and then form the posterior cerebral arteries (PCAs). The vertebral arteries are divided into four segments, of which the fourth segment is completely intracranial. The two vertebral arteries merge into the basilar artery at the pontomedullary junction. The basilar artery travels up to the pontomesencephalic junction, where it splits to form the PCAs. The basilar artery feeds the pons and midbrain through small perforator arteries. The PCA feeds the medial occipital cortex and medial temporal lobe. The vertebral arteries feed the cerebellum, specifically the posterior inferior cerebellar arteries (PICAs), and the basilar artery gives rise to the anterior inferior cerebellar arteries (AICAs) and the superior cerebellar arteries (SCAs) (Fig. 90-2). The cerebral hemispheres are each divided into four lobes. The frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital lobes are each responsible for distinct functions. The frontal lobe directs eye movements, motor speech, and orientation. The parietal lobe controls speech and sensation. The temporal lobe is responsible for speech, and the occipital lobe is the primary visual center (Fig. 90-3). Strokes affecting the deep territory cause a motor weakness (hemiparesis) involving the face, arm, and leg all on the same side. In the event the proximal left MCA is occluded, a patient will develop a stroke involving all three branches. This syndrome will combine all the symptoms with a right hemiplegia, hemianesthesia, homonymous hemianopia, and global aphasia (receptive and expressive) with a left gaze preference (Table 90-1). TABLE 90-1 Artery, Cerebral Localization, and Physical Examination Correlations ACA, Anterior cerebral artery; MCA, middle cerebral artery; PCA, posterior cerebral artery. From Blumenfeld H. Neuroanatomy through clinical cases. Sunderland, Massachusetts: Sinauer Associates; 2002.

Cerebral Functional Anatomy and Rapid Neurologic Examination

Review of Cerebral Circulation

Neurovascular Anatomy

Functional Anatomy

Left Middle Cerebral Artery Strokes

Artery

Lobe

Sign

Right ACA

Frontal, parietal

Left leg weakness

Right MCA: superior division

Frontal, parietal

Left arm/face weakness, hemineglect

Right MCA: inferior division

Temporal, parietal

Profound hemineglect, right gaze preference

Right PCA

Temporal, occipital

Left homonymous hemianopia

Left ACA

Frontal, parietal

Right leg weakness

Left MCA: superior division

Frontal, parietal

Right face/arm weakness, nonfluent aphasia

Left MCA: inferior division

Temporal, parietal

Fluent aphasia, right visual field cut

Left PCA

Temporal, occipital

Right homonymous hemianopia

Cerebral Functional Anatomy and Rapid Neurologic Examination