Carcinoma of the uterine cervix is the third most common gynecologic malignancy in the United States. According to the cancer facts and figures from the American Cancer Registry (ACR; Atlanta, GA), there were an estimated 11,000 new cases and 3800 deaths in 2008. The increased use of the Papanicolaou test as a screening tool for cervical malignancy in countries with fully developed health care systems has resulted in a decrease in the incidence and mortality rate of invasive cancer, whereas the incidence of preinvasive disease has increased. The survival rate for invasive cervical cancer, however, shows only minor improvement.

Disease

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common malignancy of the cervix, accounting for approximately 85% of all cervical carcinomas. The remaining 15% of cervical carcinomas include adenocarcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma, and undifferentiated carcinoma, which tend to have a poorer prognosis. The relative incidence of adenocarcinoma is increasing because the Papanicolaou screening test is more sensitive in detecting squamous cell carcinoma. Established risk factors for developing of cervical carcinoma include human papillomavirus infection, early sexual activity (especially with multiple partners), cigarette smoking, and immunosuppression.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

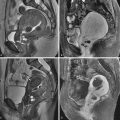

The cervix, separated from the uterine corpus by the internal os, is composed of the intravaginal portion and the supravaginal portion or isthmus ( Figure 33-1 , A ). The squamous epithelium lining the vaginal mucosa extends to cover the intravaginal cervix, whereas the supravaginal cervix is lined with mucin-producing columnar epithelium. Cervical cancer originates at the squamocolumnar junction (SCJ). During aging the squamous epithelium grows to cover the columnar cells, and the SCJ migrates cranially into the endocervical canal. This physiologic migration of the SCJ accounts for the exophytic growth pattern of cervical tumor seen more commonly in younger women and the endophytic growth pattern seen more commonly in older women ( Figure 33-3 , A ). The average age at diagnosis of patients with cervical carcinoma is 45, but the disease can occur in younger women and during pregnancy as well.

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation

Patients with cervical carcinoma may remain asymptomatic and are diagnosed routinely during screening with the Papanicolaou test. When symptomatic, patients usually present with abnormal vaginal bleeding such as intermenstrual bleeding, postcoital bleeding, or postmenopausal bleeding. The involvement of the pelvic sidewall can result in pelvic pain in some patients. Patients with advanced disease may present with symptoms secondary to invasion of adjacent structures such as flank pain caused by involvement of the ureters and resultant obstructive uropathy, or hematuria as a result of tumor invasion of the urinary tracts and the urinary bladder. Involvement of the rectum may result in bowel symptoms in some patients.

Imaging Indications and Algorithm

Accurate staging of cervical carcinoma is crucial to patient management. The current staging system for cervical carcinoma is based on the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) classification. This is a clinical staging system that defines the staging of cervical carcinoma based on clinical assessment, physical examination under anesthesia, colposcopy, endocervical curettage, hysteroscopy, cystoscopy, proctoscopy, intravenous urography, barium enema, and chest radiography.

Inaccuracies in clinical staging have been consistently reported, and clinical staging underestimates the disease compared with surgical staging in 15% to 36% of the patients. Van Nagell et al. found understaging in 22% of stage I tumors, 39% of stage II tumors, and 38% in stage III tumors, as well as overstaging in 38% of stage III tumors. Inaccuracies in clinical staging are predominantly related to difficulties in assessing and estimating endocervical tumor size and evaluating parametrial, pelvic sidewall, urinary bladder, and rectal involvement. In advanced cases there is an inability to assess distant metastasis. In clinical practice many of the radiologic and endoscopic studies outlined in the FIGO criteria are not used; rather, there is increased use of computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in clinical staging. Cross-sectional imaging modalities such as CT and MRI have yet to be incorporated into the FIGO staging algorithm. The reasons cited for this include high cost, lack of availability, and interobserver variability. This is especially true in the underdeveloped countries of the world, where screening is less common and invasive cervical cancer is more prevalent.

Although the FIGO clinical staging system does not assess lymph node metastasis, this is an important prognostic factor that also affects treatment planning. Lymph node status is predicted clinically and pathologically by the stage of the disease, tumor volume, and histologic grade. The obturator lymph nodes are typically the sentinel lymph nodes in cervical carcinoma. They are found along the lateral pelvic sidewalls where the obturator vessels enter the levator ani muscles. The lymphatic drainage of the tumor parallels the venous drainage. Lymph node involvement is also dependent on the extent of the local tumor and involvement of adjacent structures. Extension of disease into the parametria and pelvic sidewalls can result in involvement of the external iliac lymph nodes. Rectum extension can result in involvement of the inferior mesenteric and paraaortic lymph nodes. Paraaortic lymph nodes may also be involved when there is tumor extension to the pelvic sidewall or the lower third of the vagina. Involvement of the lower third of the vagina can result in involvement of the inguinal lymph nodes as well. The use of cross-sectional imaging such as CT and MRI allows detection of enlarged lymph nodes, which the radiologic studies outlined in FIGO criteria are unable to demonstrate. Furthermore, apart from lymph node status, large tumor volume and tumor extension to the uterine corpus, which have important prognostic and therapeutic implications, are also not addressed in the FIGO clinical staging system.

In staging of cervical carcinoma, it is imperative to identify early disease that can be treated with surgery or surgery combined with chemotherapy and radiation therapy (stage IA to IIA) from advanced disease that precludes surgery and must be treated with radiation therapy or combined radiation and chemotherapy (stage IIB to IV). The available imaging modalities must be used and directed to help answer this clinically crucial question.

Imaging Technique and Findings

Radiography

Chest radiography outlined in the FIGO criteria is performed in staging to identify pulmonary masses from cervical carcinoma metastases. Pulmonary metastases, however, are a late manifestation of advanced cervical carcinoma. Chest CT will be a more sensitive modality in identifying small pulmonary metastases in clinically high-risk patients.

Intravenous urography is an investigation listed in FIGO criteria. It is sensitive in demonstrating the extent and the level of hydronephrosis in patients with advanced cervical carcinoma.

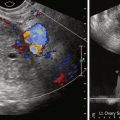

Ultrasound

Transabdominal ultrasound (US) can be performed to identify hydronephrosis resulting from involvement of the distal ureters by the primary cervical tumor. It is also useful in screening for hepatic metastases, which again are a late manifestation of advanced disease. Transabdominal and transvaginal US have a limited role in assessing the local extent of the primary cervical tumor. Assessment of locally advanced tumor with parametrial and pelvic sidewall involvement is suboptimal with US. This is due to the small field of view and limited soft tissue contrast resolution.

Computed Tomography

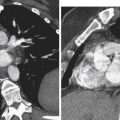

CT is a widely available and robust imaging modality, useful for staging of distant metastasis in advanced disease. It has limited value in the local staging of early cervical carcinoma because of the inferior soft tissue contrast resolution in the pelvis compared with MRI. The major limitation of CT in local staging is the inadequacy in differentiating between tumor, normal cervical tissue, and parametrial tissue. Visualization of the primary tumor is difficult, and CT is predominantly used in assessing distant metastasis and lymph node status ( see Figure 33-10 , A ). According to the ACR Appropriateness Criteria for staging of cervical carcinoma, CT has been assigned an appropriateness rating of 5 compared with 8 to 9 for MRI (rating scale: 1 = least appropriate, 9 = most appropriate). There is a consensus in the published literature that the value of CT increases with higher stages of disease, and it has limited value in evaluation of early parametrial invasion in stage IIB disease. A recent American College of Radiology Imaging Network trial reported that CT has a sensitivity of 14% to 38% and specificity of 84% to 100% in detecting parametrial invasion. CT and MRI have been found to have similar sensitivity and specificity in lymph node assessment. Similar to MRI, CT depends on size criteria as well, and hence lymph nodes with microscopic metastasis will be missed. In addition to assessing distant metastasis and lymph node status, CT is also used for image-guided interventions and also radiotherapy planning.

Magnetic Resonance

Cervical anatomy is accurately demonstrated on high-resolution, small field-of-view T2-weighted images. Normal cervical stroma is uniformly hypointense, and the mucosa lining of the endocervical canal is hyperintense on T2-weighted images. The internal os is defined as the level of entry of the uterine vessels and separates the lower uterine segment from the endocervix. The caudal portion of the cervix protrudes into the vagina and is surrounded by the vaginal fornices (see Figures 33-1 and 33-2 ). At the lateral aspect of the cervical isthmus, the pericervical ligaments comprising the uterosacral and cardinal ligaments form the parametrium. These are mildly hyperintense on high-resolution T2-weighted images (see Figure 33-1 , B ).

The vagina is divided into the upper, middle, and lower third. The lower third of the vagina has a different embryologic origin from the proximal two thirds of the vagina. The vaginal vault is uniformly hypointense whereas the vaginal mucosa is hyperintense on T2-weighted images.

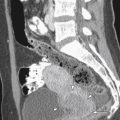

There is an increasing role for MRI in staging of cervical malignancy. MRI is not used for detection of carcinoma but for staging of cytologically or histologically proven disease. MRI has superior accuracy in determining the size and location of the tumor, be it demonstrating a tumor with an exophytic or endophytic growth pattern. The superior soft tissue contrast resolution of MRI makes it an ideal imaging modality for staging of cervical carcinoma. In a study comparing MRI staging with surgical staging, Hricak et al. reported overall similar staging accuracy of MRI (81%) and FIGO (79%). In patients with stage II and above disease, the overall accuracy of MRI decreased to 74%, whereas that of FIGO clinical staging decreased to 53%. The superiority of MRI over clinical staging in advanced disease has consistently been reported. Similarly, MRI surpasses CT in evaluation of local extent of the tumor, showing increased accuracy in assessing depth of cervical stroma and parametrial invasion. MRI has been found to be a cost-effective staging tool. In a cost-effectiveness study of patients with cervical carcinoma, those who underwent MRI as the initial staging procedure required fewer tests and procedures compared with those who underwent standard clinical staging and imaging. Using the ACR Appropriateness Criteria, MRI has been assigned a rating of 8 for stage IB1 tumors and a rating of 9 for stage IB2 tumors and above.

T2-weighted sequences are the most important sequences for staging of cervical carcinoma because they provide optimal contrast resolution between the tumor and the cervical stroma. High-resolution, small field-of-view images are performed in axial, coronal, and sagittal planes. Optional oblique plane images perpendicular to the axis of the endocervical canal may be performed, and this may further improve staging accuracy. The cervical tumor is moderately hyperintense on T2-weighted images and in contrast to the homogeneously hypointense normal cervical stroma. In general, staging of cervical carcinoma with MRI is based on the classification system of the FIGO clinical staging system ( Table 33-1 ).

| Primary Tumor (T) | ||

|---|---|---|

| TNM Categories | FIGO Stages | |

| TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed | |

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumor | |

| Tis * | Carcinoma in situ (preinvasive carcinoma) | |

| T1 | I | Cervical carcinoma confined to uterus (extension to corpus should be disregarded) |

| T1a † | IA | Invasive carcinoma diagnoses only by microscopy Stromal invasion with a maximum depth of 5.0 mm measured from the base of the epithelium and a horizontal spread of ≤7.0 mm; vascular space involvement, venous or lymphatic, does not affect classification |

| T1a1 | IA1 | Measured stromal invasion ≤3.0 mm in depth and ≤7.0 mm in horizontal spread |

| T1a2 | IA2 | Measured stromal invasion >3.0 mm in depth and not more than 5.0 mm with a horizontal spread ≤7.0 mm |

| T1b | IB | Clinically visible lesion confined to the cervix or microscopic lesion >T1a/IA2 |

| T1b1 | IB1 | Clinically visible lesion ≤4.0 cm in greatest dimension |

| T1b2 | IB2 | Clinical visible lesion >4.0 cm in greatest dimension |

| T2 | II | Cervical carcinoma invades beyond uterus but not to pelvic wall or to lower third of vagina |

| T2a | IIA | Tumor without parametrial invasion |

| T2a1 | IIA1 | Clinically visible lesion ≤4.0 cm in greatest dimension |

| T2a2 | IIA2 | Clinically visible lesion >4.0 cm in greatest dimension |

| T2b | IIB | Tumor with parametrial invasion |

| T3 | III | Tumor extends to pelvic wall and/or involves lower third of vagina, and/or causes hydronephrosis or nonfunctioning kidney |

| T3a | IIIA | Tumor involves lower third of vagina, no extension to pelvic wall |

| T3b | IIIB | Tumor extends to pelvic wall and/or causes hydronephrosis or nonfunctioning kidney |

| T4 | IVA | Tumor invades mucosa of bladder or rectum, and/or extends beyond true pelvis (bullous edema is not sufficient to classify a tumor as T4) |

| Regional Lymph Nodes (N) | ||

| TNM Categories | FIGO Stages | |

| NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed | |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis | |

| N1 | IIIB | Regional lymph node metastasis |

| Distant Metastasis (M) | ||

| TNM Categories | FIGO Stages | |

| M0 | No distant metastasis | |

| M1 | IVB | Distant metastasis (including peritoneal spread, involvement of supraclavicular, mediastinal, or paraaortic lymph nodes, lung, liver, or bone) |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree