CHRONIC OTOMASTOIDITIS AND ACQUIRED CHOLESTEATOMA

KEY POINTS

- Non–contrast-enhanced computed tomography can establish the extent of disease with precision and help with sometimes markedly alter surgical planning.

- Soft tissue changes alone are nonspecific and cannot exclude the presence of chronic erosive middle ear disease.

- Ossicular erosions can be seen in both erosive chronic otomastoiditis and cholesteatoma.

- Both bone and soft tissue changes are critical to proper assessment.

- Imaging can occasionally drastically alter the diagnosis and medical decision making.

INTRODUCTION

Etiology

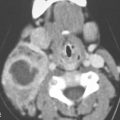

Acquired cholesteatoma is a complication of recurrent acute otitis media (AOM), chronic eustachian tube dysfunction, chronic suppurative otitis media (CSOM), and chronic otitis media with effusions (COME). These conditions may be manifest by recurrent pyogenic middle ear infections, negative middle ear pressure, and tympanic membrane perforation. Since this disease may be related to acute or chronic eustachian tube dysfunction leading to decrease in intratympanic pressure and secretory otitis media, adults with unilateral disease and an obstructing lesion along the eustachian tube must be excluded (Fig. 111.1). Tubal dysfunction increases the risk of respiratory-borne pathogens ascending the tube to infect the middle ear.

During AOM and CSOM, the tympanic membrane typically becomes thick whereas it becomes thin with COME and eustachian tube dysfunction. Squamous epithelium may grow through or within the areas of perforation and retraction pockets. The continuous sloughing of this normal desquamating epithelium within the confines of the middle ear produces a cholesteatoma. Alternatively, chronic otitis media (COM) can lead to squamous metaplasia of the middle ear, respiratory epithelium, and the same sequence of events. Such chronic inflammation can also lead to the middle ear mucosa turning into a mass of essentially chronic granulation tissue that will erode surrounding bone, including the ossicles. This process may go on to dense mucoid impaction sometimes referred to as “glue ear” or end-stage retractile fibrosis.

Acquired cholesteatoma usually arises in the pars flaccida, the superior portion of the tympanic membrane also known as the Schrapnell membrane, and extends into the Prussak space. Synonyms for pars flaccida cholesteatoma are Prussak space cholesteatoma and attic cholesteatoma. Less commonly, the cholesteatoma arises from the pars tensa of the tympanic membrane, extending into the facial recess and tympanic sinus sometimes referred to as sinus cholesteatoma. Cholesteatoma can also extend or originate in the anterior epitympanic recess, posing a surgical risk to the anterior genu and proximal part of the tympanic segment of the facial nerve.

FIGURE 111.1. Chronic serous otitis media in an adult. Axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance image obliteration of the left middle ear cavity and mastoid is caused by obstruction of the eustachian tube due to an early infiltrating nasopharyngeal cancer (arrows).

Prevalence and Epidemiology

This is a common sporadic condition that is seen in all age groups. In adults, unilateral COM with or without cholesteatoma must be considered due to an obstructing eustachian tube mass, possibly cancer, until proven otherwise.

Clinical Presentation

The clinical setting of CSOM and physical findings including a perforated tympanic membrane and visible cholesteatoma usually make radiologic “diagnosis” of cholesteatoma a moot issue. In this case, they present for imaging to establish the extent of disease. Patients may also present with CSOM without obvious cholesteatoma or infection; this prompts a search for a mass obstructing the eustachian tube, especially if the disease is unilateral and in an adult (Fig. 111.1). Other complaints that might be attributed to this disease include otalgia, headache, and conductive or mixed hearing loss.

The otologic surgeon may also be looking for complications of CSOM, with or without cholesteatoma, and mastoiditis. This can expand the type of clinical presentations in the preceding paragraph to include vestibular symptoms (nausea, vomiting, dizziness, vertigo) and, if acute, those associated with possible intracranial spread of disease discussed in conjunction with acute otomastoiditis discussed in Chapter 110. Since the imaging study must be performed with contrast when looking for complications, it is essential to establish if this is a serious clinical consideration when setting up a particular patient’s protocol.

Pathophysiology

Anatomy

A thorough knowledge of the following normal anatomy and its normal variations is essential in evaluating this disease state and is discussed in detail in Chapter 104 and summarized here.

For the primary site of disease origin:

Middle ear, including the tympanic ring and membrane, scutum, Prussak space, ossicles, tympanic sinus, and facial recess; mastoid, including the mastoid antrum, Koerner septum, central mastoid canal, and sigmoid plate

Middle ear, including the tympanic ring and membrane, scutum, Prussak space, ossicles, tympanic sinus, and facial recess; mastoid, including the mastoid antrum, Koerner septum, central mastoid canal, and sigmoid plate

For spread beyond the mastoid and middle ear:

Roof of the middle ear and mastoid, perilabyrinthine air cell tracts

Roof of the middle ear and mastoid, perilabyrinthine air cell tracts

For facial nerve complications:

Entire course of the facial nerve through the temporal bone

Entire course of the facial nerve through the temporal bone

For spread to the inner ear:

Round window, oval window, cochlea, and semicircular canals

Round window, oval window, cochlea, and semicircular canals

For complications related to intracranial spread:

Sigmoid sinus, jugular bulb, petrosal sinuses, other major dural venous sinuses, vein of Labbé, and inferior surface of the temporal lobe

Sigmoid sinus, jugular bulb, petrosal sinuses, other major dural venous sinuses, vein of Labbé, and inferior surface of the temporal lobe

Pathology and Patterns of Disease

Chronic Nonerosive, Erosive, and Adhesive Otitis Media

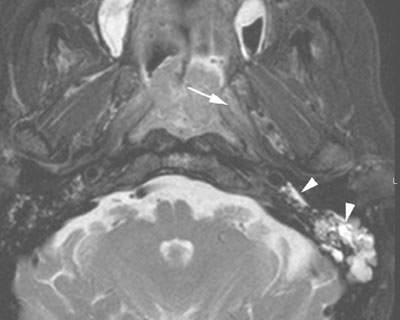

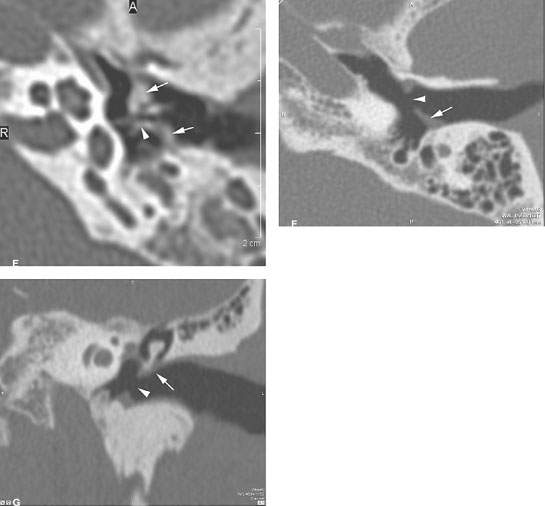

The tympanic membrane may appear thickened, retracted, perforated, and/or calcified (Fig. 111.2). The first three changes are nonspecific and may be an acute or chronic change. Calcification or at least increased density of the tympanic membrane and/or the middle ear contents is due to COM with tympanosclerosis, a condition associated with a high pO2 resulting from tympanostomy tubes or perforation. The dense material is due to a hyalinizing reaction of ossicular ligaments, middle ear, and mastoid mucosa and submucosa of the tympanic membrane. It is simply due to progressive calcification of granulation tissue surrounding these structures (Fig. 111.2). Dense calcification or ossification beyond the tympanic membrane to the ossicles and ligaments is indicative of advanced disease (Fig. 111.3). This process may lead to ossicular fixation and obliteration of the round window niche and mastoid. This worsens the prognosis for osseous reconstruction. It is rarely seen in ears not violated by tympanostomy tubes or by perforations of the tympanic membrane. On computed tomography (CT), these changes may appear relatively subtle, being manifest by increased density and thickening of ossicular ligaments, lateral fixation of the ossicles, and indistinctness of the usually obviously patent round window.

Active granulation tissue can result in osteoclastic resorption of the ossicles or bone of the mastoid and in extreme cases otic capsule. This process has been called chronic erosive otitis media (Fig. 111.4). The associated rarefying osteitis can facilitate the spread of disease intracranially, to the labyrinth or to major vascular structures. The ossicular erosion as seen on CT may be indistinguishable from that caused by cholesteatoma. The long process of the incus is most subject to erosion (Fig. 111.4). In cholesteatoma, the soft tissue findings usually appear more localized and ossicular displacement may be seen. However, chronic erosive otitis media and cholesteatoma commonly coexist; the main role of imaging is to show the extent of disease rather than to “make a diagnosis.” Cholesteatoma may also obstruct the mastoid antrum and may promote infection or inflammation in the mastoid (Fig. 111.2C). Postobstructive cholesterol granuloma may then be seen in the mastoid. The diagnosis of cholesteatoma is usually obvious to the otologic surgeon (Figs. 111.5 and 111.6); exceptions to this include early congenital cholesteatoma (Fig. 111.7) and those that occur in congenitally deformed ears discussed in Chapter 105 (Fig. 107.2).

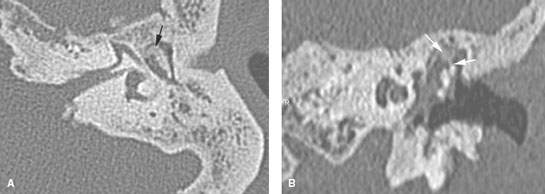

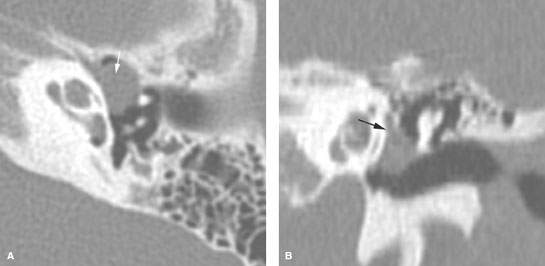

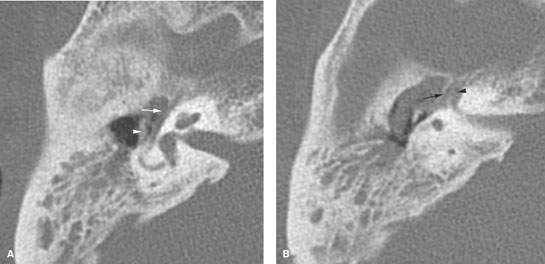

FIGURE 111.2. A–E: Tympanic membrane (TM) changes in chronic middle ear disease. Mild tympanosclerosis manifest by a thick, dense TM (arrows in A) with retraction and perhaps calcification (arrow in B). This was associated with chronic otitis media and a mastoid cholesteatoma. Note the blunted scutum (arrowhead in A) and the erosion of the Koerner septum (arrows in C) as well as remodeling of the antral wall (arrowhead in C). In another patient, tympanosclerosis is seen in its advanced form with thickening retraction and likely calcification (arrows in Dand E) and incorporation of the incudostapedial joint (arrowhead in E) in the extensively thickened TM. F, G: Thickened tympanic membrane (arrows) and a large central perforation (arrowheads).

The soft tissue changes seen in these and other middle ear abnormalities are nonspecific. Mucosal inflammation and granulation tissue will enhance. On noncontrast magnetic resonance (MR) or CT, mucosal thickening, submucosal edema, granulation tissue, tumor, and cholesteatoma are indistinguishable (Fig. 111.8). Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance (CEMR) may distinguish cholesteatoma as a nonenhancing mass from inflammatory diseases (Fig. 111.9). Recall that cholesteatoma may coexist with granulation tissue and that loculated fluid in the middle ear or mastoid will not enhance. So while CEMR might be able to distinguish cholesteatoma from other middle ear abnormalities in selected cases, the usual ease of clinical diagnosis and the potential pitfalls of imaging diagnosis make the expenditure of resources unnecessary for this purpose alone except for in highly selected circumstances (Figs. 111.8 and 111.9). Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) might help with differentiating these disease processes, but it is likely cost justified only in highly selected cases (Fig. 111.8.F–H).

FIGURE 111.3. Chronic adhesive otitis media. On the left (A, B), soft tissue changes are seen in the middle ear cavity in a patient with long-standing otitis media. Secondary to the inflammation, fibro-osseous material has formed in the epitympanum, resulting in fixation of the malleal head to the epitympanic tegmen.

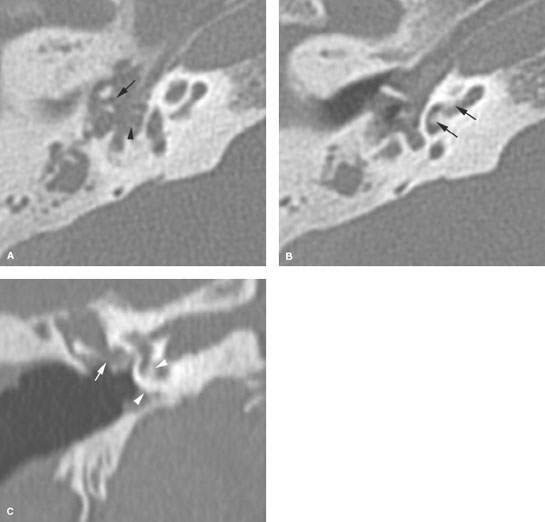

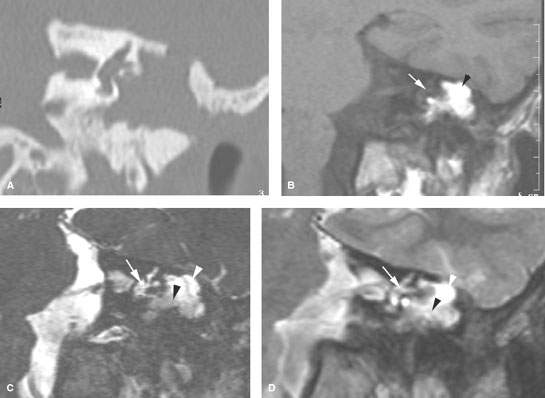

FIGURE 111.4. Chronic erosive otitis media. Tissue fills the middle ear cavity. A: The malleus head and incus body are eroded (arrows) but the stapes is not eroded (arrowhead). B: There is secondary fibrosseous change in the cochlea (arrows) C: The fibrosseous obliteration started from the round window (arrowheads). The incus long process is demineralized. On four contiguous axial computed tomography images, opacification of the middle ear due to otitis media and mastoidectomy cavity is seen. The long-standing otitis media resulted in erosive changes of the head of the malleus and the long process of the incus.

Cholesteatoma

The tympanic membrane often becomes thickened when inflamed or infected and retracted and/or perforated when the disease is more quiescent. Squamous epithelium may grow through or within the areas of perforation and retraction pockets. The tympanic membrane collapses on the promontory, incus, and stapes. This pocket deepens until exfoliated skin can no longer migrate laterally, which results in the trapped debris, along with body heat and moisture, promoting growth of microorganisms. Secreted toxins stimulate a host inflammatory response, including recruitment of white blood cells, formation of granulation tissue, and more rapid turnover of the squamous epithelium. Alternatively, COM and certain toxins can lead to squamous metaplasia of the middle ear, respiratory epithelium, and the same sequence of events.

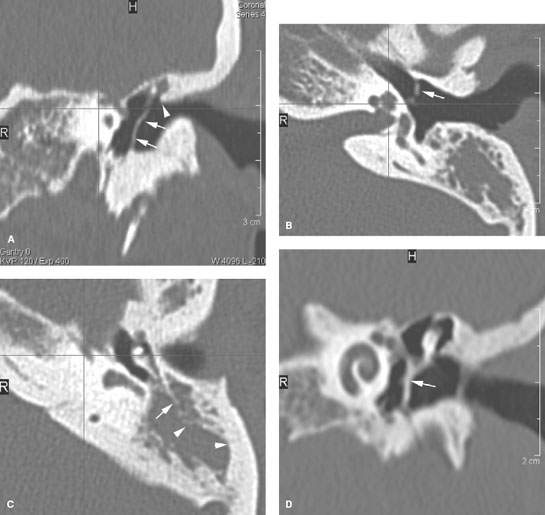

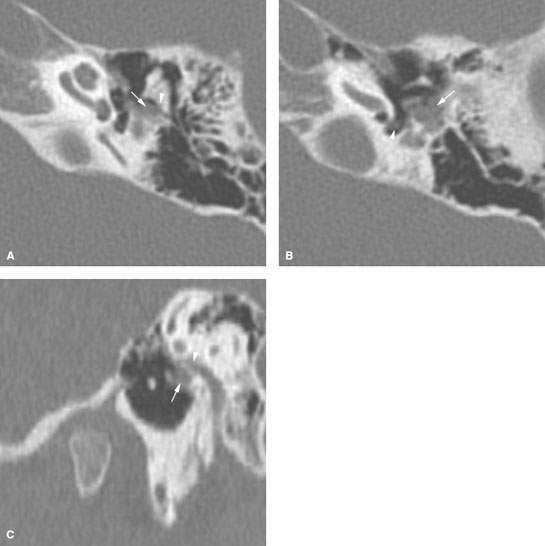

Once formed, cholesteatoma becomes a disease that can spread within the tympanic cavity and mastoid to points very remote from the site of origin. It can also “grow” beneath or along the periosteum; thus, some of its extent might not be visible by inspection of the mucosa during surgery. Particularly important are extension to the anterior tympanic recess and first genu of the facial nerve (Fig. 111.10), tympanic sinus (Fig. 111.11), and along air cell tracts to the petrous apex; all of these extensions of disease may be unanticipated prior to imaging and markedly alter the surgical approach. Erosion of the bone over the lateral semicircular canal is not uncommon and can lead to injury of the membranous labyrinth that can result in deafness and dizziness (Fig. 111.10E); such erosion of the posterior semicircular canal is far less common.

When seen as an isolated finding, cholesteatoma is usually round to lobulated, well-circumscribed masses (Figs. 111.5–111.10). Acquired cholesteatoma most commonly originates in the Prussak space, lateral to the ossicles (Fig. 111.5). The adjacent scutum, the lateral wall of the epitympanic recess, is often eroded. The ossicles may be normal, displaced, demineralized, or eroded (Figs. 111.5–111.12). The long process of the incus is most subject to erosion. The imaging confirmation of cholesteatoma depends on identifying a soft tissue mass that erodes bone in a circumscribed fashion, generally centrally within the upper mesotympanum and/or mastoid and may displace or erode the ossicles. This is in contrast to more diffuse erosive but uncommon diseases such as eosinophilic granuloma, tuberculosis, and tumors that cause much different erosive patterns.

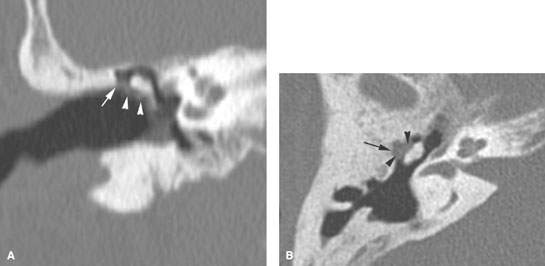

FIGURE 111.5. Acquired cholesteatoma in the Prussak space (pars flaccida cholesteatoma). On axial images, a soft tissue mass is seen lateral to the ossicles (A, B). The coronal plane shows that the mass is located in the Prussak space and has caused erosion of the scutum.

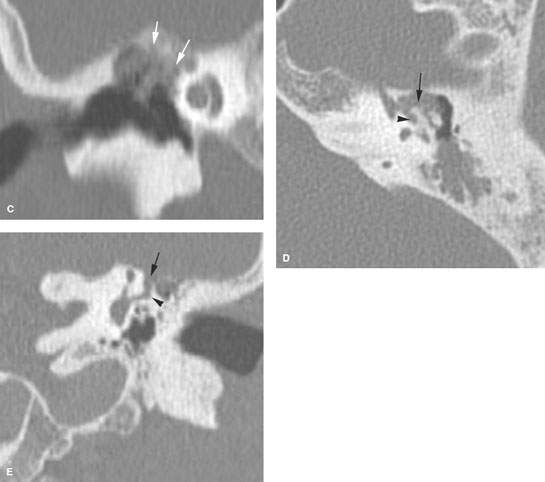

FIGURE 111.6. Pars tensa cholesteatoma. The cholesteatoma (white arrow) originates in the posterior superior part of the tympanic membrane and extends into the facial recess (arrowheadin A) and more medially into a small sinus tympani (arrowhead in B). C: Also note the subperiosteal extension (arrow) along the external auditory wall coming close to the facial canal (arrowhead).

FIGURE 111.7. Congenital cholesteatoma. A round soft tissue mass is seen on the promontory, inferior medial to the ossicles (arrows in A and B).

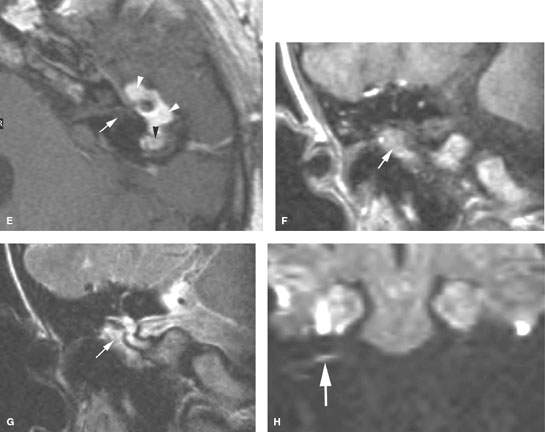

FIGURE 111.8. Two patients with surgically proven cholesteatoma. A–E: Patient 1. In (A), the coronal computed tomography study shows cholesteatoma within the middle ear cavity and eroding its roof. In (B), the non–contrast-enhanced T1-weighted (T1W) image shows the cholesteatoma to be bright (arrowhead). The vestibule is shown as a landmark for the plane of section. In (C), the steady state image again is shown with the vestibule (white arrow) for reference. Note that the material within the middle ear and mastoid shows a brighter signal superiorly (white arrow) than inferiorly (black arrowhead). In (D), a T2-weighted (T2W) image is shown to correlate with the steady state image seen in (C). The vestibule (arrow) identifies the comparable plane of section, and the variable signal intensity of the cholesteatoma is shown by the white and black arrowhead. (continued) In (E), the contrast-enhanced T1W image shows variable signal intensity of the material in the middle ear and mastoid (white and black arrowhead). The vestibule marks the plane of section (arrow). There is not obvious contrast enhancement because of the inherently increased signal intensity. F–H: Patient 2. Non–contrast-enhanced T1W image in (F) shows high intensity material within the middle ear cavity that also is of relatively high signal intensity on the coronal T2W image in (G) (arrows). In (H), the arrow shows restricted diffusion on an echo planar, b 51,000 image (arrow), suggesting cholesteatoma that was surgically proven. (Case courtesy of R. Hermans.)

Cholesteatoma may spread along pre-existing air cell tracts to the perilabyrinthine region and even to the petrous apex; this behavior is seen in both the congenital and acquired form of the disease and, if noted, can help the otologic surgeon anticipate the possible need to extend the usual approach into these more remote sites of involvement (Fig. 111.10).

Particularly tenacious cholesteatoma, especially recurrent disease, may spread subperiosteally. This is sometimes difficult to recognize even at surgery. In highly selected cases, high-resolution T2-weighted MR may show such spread beneath the dura or periosteum that borders the middle and posterior cranial fossa; this could also be of value in surgical planning (Fig. 111.8).

While cholesteatoma can usually be dissected from the facial nerve canal, it is useful to understand whether the bony covering is dehiscent compared to the normal side, or if the disease has followed the canal toward the anterior genu. The facial recess and tympanic sinus are often diseased; absence of CT abnormality in these excludes all but minimal mucosal disease at these important sites (Figs. 111.10–111.12). The bony covering over the lateral semicircular canal may also be noted.

The primary sign of a cholesteatoma on CT or MR is a soft tissue mass. Cholesteatoma may coexist with granulation tissue, fibro-osseous changes, mucosal inflammation, fluid, or even other less common masses; thus, the presence of abnormal soft tissue is a nonspecific finding. This leads to significant limitations of CT and MR in distinguishing between cholesteatoma and other soft tissue abnormalities. The diagnosis is less important that the disease extent for medical decision making.

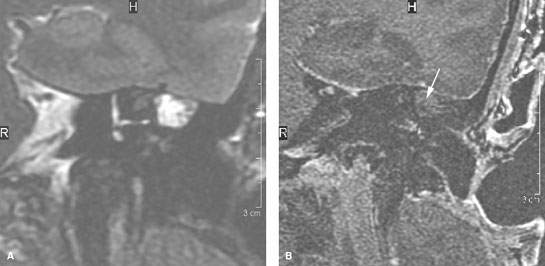

FIGURE 111.9. A, B: Magnetic resonance study of a patient with a proven cholesteatoma that behaves somewhat more typically than those seen in Figure 111.8. Coronal T2-weighted image (A) shows the cholesteatoma in the mastoid antrum to be bright. T1-weighted image with contrast in (B) shows no enhancement (arrow).

Pathologically Altered Function

Middle ear and mastoid disease primarily causes conductive hearing loss.

Advanced disease can cause labyrinthitis and lead to vestibular dysfunction and sensorineural hearing loss (Fig. 111.10). Advanced disease can also lead to facial weakness, and nerve function may be completely and irreversibly interrupted due to COM.

FIGURE 111.10. A, B:Patient 1.Advanced cholesteatoma spreading to involve the anterior genu of the facial nerve region. In (A), the axial image through the epitympanum shows the eroded ossicles (arrowhead) and cholesteatoma eroding into the facial canal (arrow) just posterior to the first genu. In (B), a section slightly cephalad shows the first genu of the facial nerve (arrowhead) and a remaining thin bony remnant with extensive adjacent cholesteatoma (arrow). (continued) C: Patient 2. A coronal image of a situation similar to that in (A) and (B) showing cholesteatoma spreading within the roof of epitympanum and causing demineralization of the overlying bone that extends to cover the lateral aspect of the first genu of the facial nerve (arrows). D: Patient 3, illustrating how cholesteatoma can spread through bone or beneath the periosteum as it invades the region of the first genu. The cholesteatoma has followed the first genu of the facial nerve anteriorly and medially (arrow) to grow into the lateral aspect of the petrous apex. A component then also extends posteriorly (arrowhead) toward the lateral semicircular canal. E: Coronal section of Patient 4. The cholesteatoma grows toward the petrous apex (arrow) and extends not only medially but also inferiorly to produce an erosion of the lateral semicircular canal in a slightly atypical fashion from directly superiorly (arrowhead).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree