Chapter 10 Clinical Breast Problems and Unusual Breast Conditions

The Male Breast: Gynecomastia and Male Breast Cancer

Broad categories of conditions causing gynecomastia include high serum estrogen levels from endogenous or exogenous sources, low serum testosterone levels, endocrine disorders (hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism), systemic disorders (cirrhosis, chronic renal failure with maintenance by dialysis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), drug-induced (cimetidine, spironolactone, ergotamine, marijuana, anabolic steroids, estrogen for prostate cancer), tumors (adrenal carcinoma, testicular tumors, pituitary adenoma), or idiopathic (Box 10-1). Gynecomastia can occur at any age, but it may be seen in particular in neonates as a result of maternal estrogens circulating to the fetus through the placenta, in healthy adolescent boys 1 year after the onset of puberty because of high estradiol levels, or in older men as a result of decreasing serum testosterone levels.

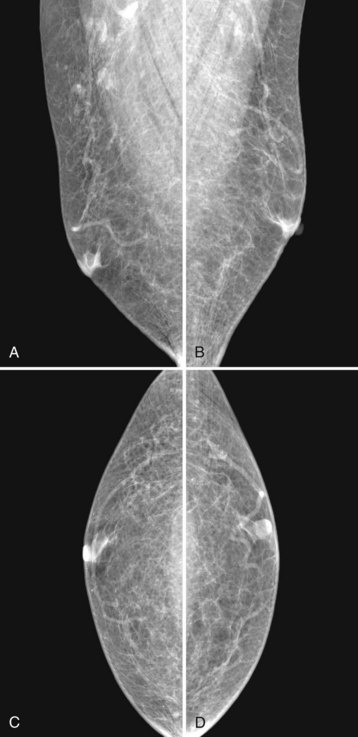

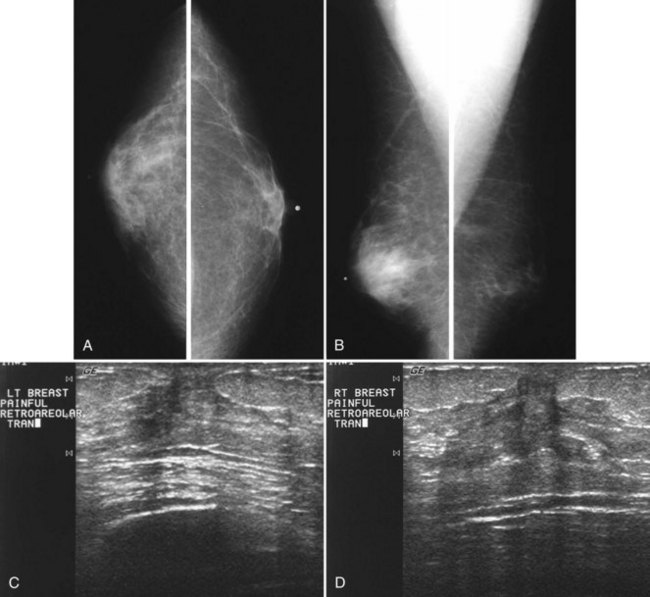

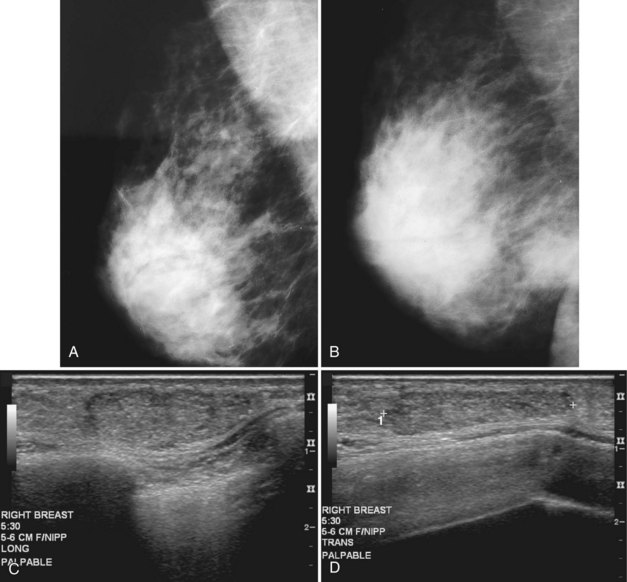

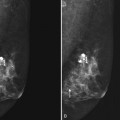

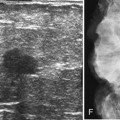

Mammography is performed in men in the same fashion as in women. On the mammogram, the normal male breast consists of fat without obvious fibroglandular tissue, and the pectoralis muscles are usually larger than in women (Fig. 10-1A to D). In both pseudogynecomastia and in women with Turner syndrome, mammograms consist mostly of fat, similar to the normal male breast (see Fig. 10-1E and F).

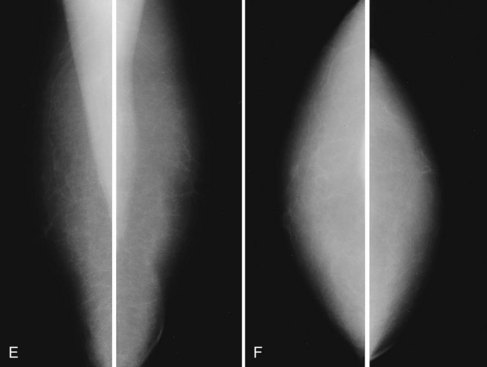

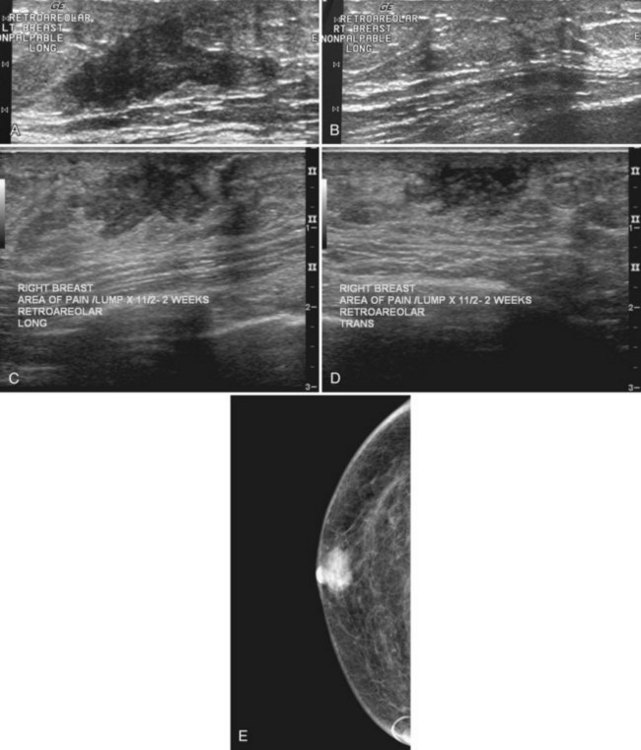

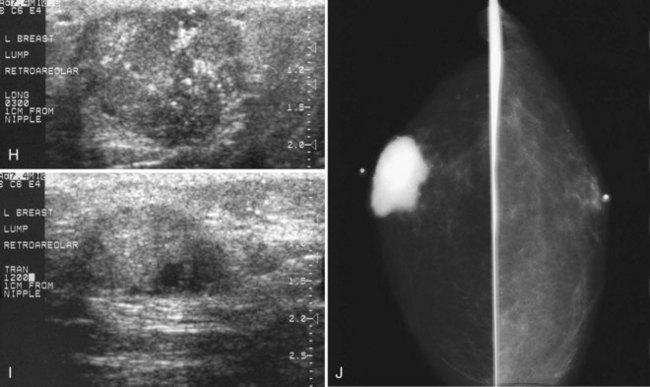

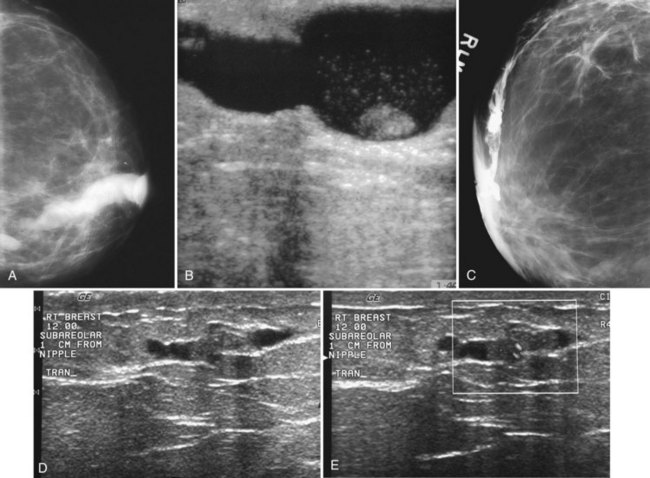

On the mammogram, gynecomastia is shown as glandular tissue in the subareolar region that is symmetric or asymmetric, unilateral or bilateral. In a large series by Gunhan-Bilgen and colleagues, gynecomastia was unilateral in 45% and bilateral in 55% of 206 cases on mammograms. In the early phases of gynecomastia, the glandular tissue takes on a flamelike dendritic appearance consisting of thin strands of glandular tissue extending from the nipple, similar to fingers extending posteriorly toward the chest wall (Table 10-1). With continued proliferation of breast ducts, the glandular tissue takes on a triangular nodular shape behind the nipple in the subareolar region that can be symmetric or asymmetric (Fig. 10-2). If the etiology of the gynecomastia is not eliminated, the proliferation may progress to the appearance of diffuse dense tissue in the later stromal fibrotic phase that is irreversible (Fig. 10-3). On ultrasound, gynecomastia shows hypoechoic flamelike, fingerlike, or triangular structures extending posteriorly toward the chest wall from the nipple (Fig. 10-4). Pseudogynecomastia shows only fatty tissue on the mammogram and is distinguished from gynecomastia by the absence of glandular tissue.

Table 10-1 Mammographic Appearance of Gynecomastia

| Type | Mammography | Gynecomastia |

|---|---|---|

| Normal | Fatty breast | N/A |

| Pseudogynecomastia | Fatty breast | N/A |

| Dendritic | Prominent radiating extensions | Epithelial hyperplasia |

| Nodular | Fan-shaped triangular density | Later phase |

| Diffuse | Diffuse density | Dense fibrotic phase |

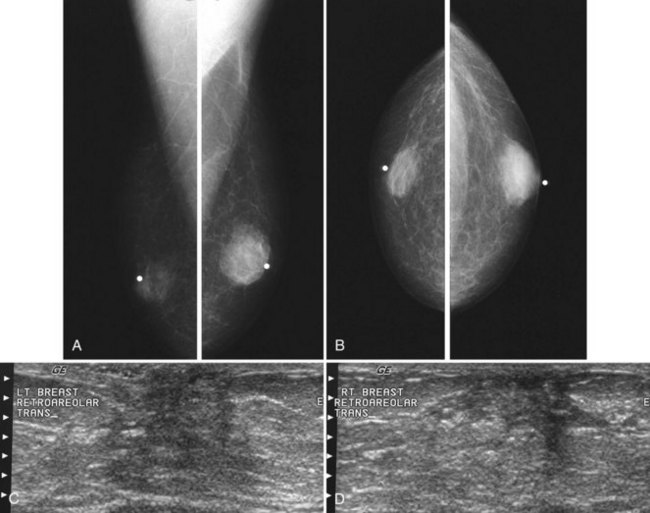

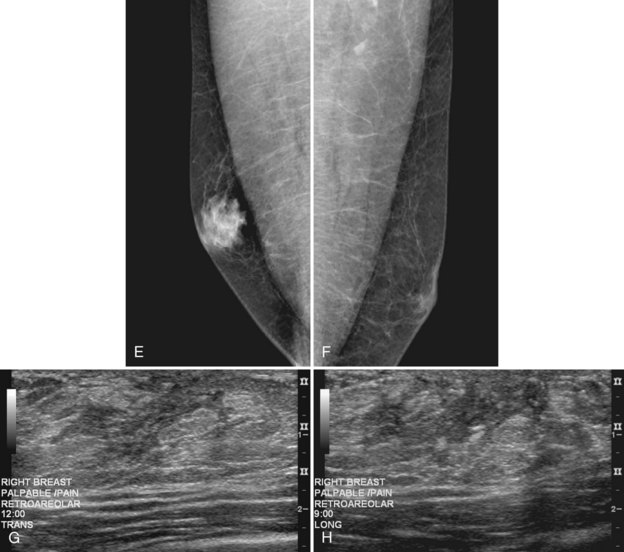

Male breast cancer accounts for less than 1% of all cancers found in men and is usually diagnosed at or around age 60, older than the mean age for the diagnosis of breast cancer in women (Box 10-2). Male breast cancer has the same prognosis as breast cancer in women, but it is often detected at a higher stage than in women because of delay in diagnosis; up to 50% of men have axillary adenopathy at initial evaluation. Risk factors include Klinefelter syndrome, high estrogen levels such as from prostate cancer treatment, and the development of mumps orchitis at an older age. Male breast cancer is generally manifested as a hard, painless, subareolar mass eccentric to the nipple. When not subareolar, cancers in men are usually found in the upper outer quadrant. Clinical symptoms of nipple discharge or ulceration are not rare in association with male breast cancer.

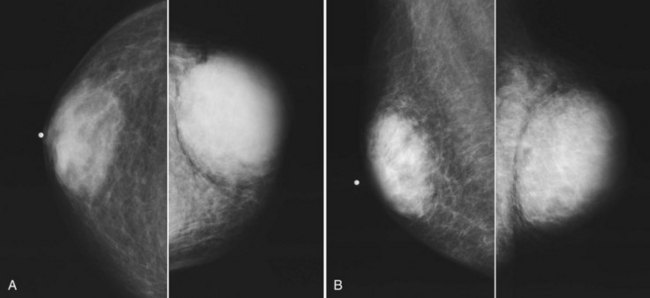

On mammography, male breast cancers are generally dense noncalcified masses with variable margin patterns located in the subareolar region (Figs. 10-5 and 10-6). Calcifications are less common in male than female breast cancer, although calcifications may be present. On ultrasound, male breast cancers are described as masses with well-circumscribed or irregular margins. Concomitant findings of skin thickening, adenopathy, and skin ulceration are associated with a poor prognosis. Breast cancers in men have the histologic appearance of invasive ductal cancer in 85% of cases, with most of the remaining tumors being medullary, papillary, and intracystic papillary tumors. An associated component of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) may be present. Invasive lobular carcinoma is rare. Treatment of breast cancer is the same for men as for women and consists of surgery, axillary node dissection, chemotherapy, radiation therapy for invasive tumors, or any combination of these treatments; the prognosis is identical as that for women.

Pregnant Patients and Pregnancy-Associated Breast Cancer

Pregnancy produces a proliferation of glandular breast tissue that results in breast enlargement and nodularity; rarely, the condition progresses to gigantomastia or enlargement of multiple fibroadenomas. Breast masses are difficult to manage in a pregnant patient because of the surrounding breast nodularity and size increase over time. Most masses occurring in pregnancy are benign and include benign lactational adenomas, fibroadenomas, galactoceles, and abscesses (Box 10-3), but the diagnosis of exclusion is pregnancy-associated breast cancer.

Pregnancy-associated breast cancer is defined as breast cancer discovered during pregnancy or within 1 year of delivery (Box 10-4). The incidence of breast cancer in pregnant women is 0.2% to 3.8% of all breast cancers, or 1 in every 3000 to 10,000 pregnancies. Most pregnancy-associated breast cancers are invasive ductal cancer. These cancers are generally manifested as a hard mass, but they may be associated with bloody nipple discharge or findings of breast edema. The usual initial imaging test in a pregnant patient is breast ultrasound. Many patients are reluctant to undergo mammography because of concern about the effect of radiation on the fetus. However, if cancer is a clinical concern, it is important to perform mammography as part of the evaluation and in particular to detect the presence of suspicious calcifications that are often nonpalpable. The amount of scattered radiation delivered to the fetus is minimal and can be further reduced with lead shielding. Swinford and colleagues showed that breast density on mammography ranges from scattered fibroglandular density in pregnant patients to heterogeneously dense or dense breasts in a lactating patient. In their series, mammography was as useful as it is in nonpregnant women with clinical signs and symptoms of breast disease. In lactating patients, breast density can be reduced on the mammogram by pumping milk from the breasts before the study.

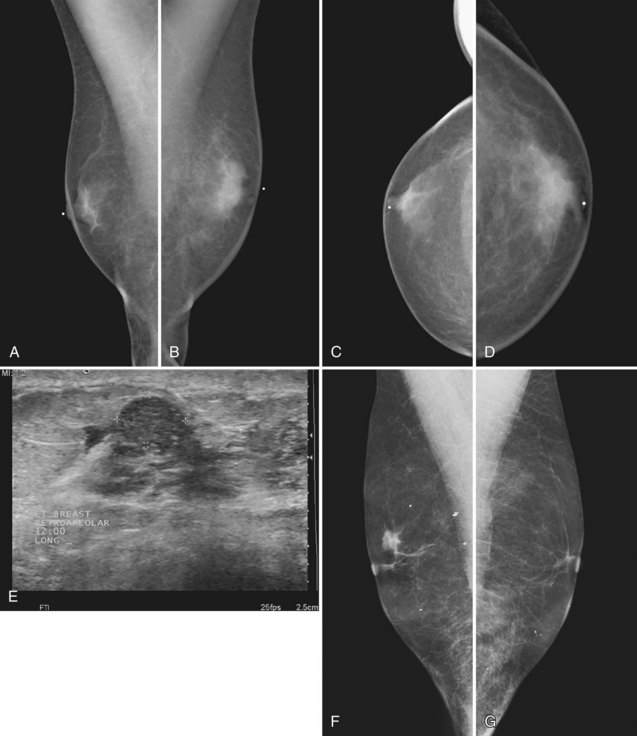

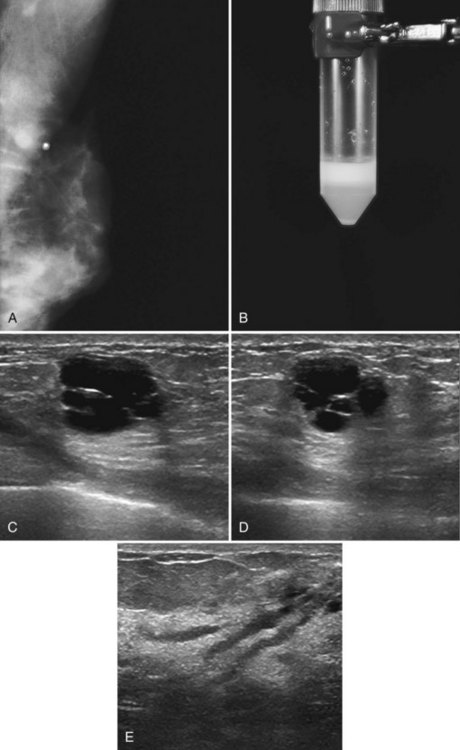

Benign conditions are the most frequent cause of breast masses in pregnant or lactating patients, and cancer is much less common. Lactational mastitis is a common complication of breast-feeding in which the breast becomes painful, indurated, and tender, usually as a result of Staphylococcus aureus infection. A cracked nipple may be the port of entry for the infecting bacteria, but it can be prevented by good nipple hygiene and care, along with frequent nursing to avoid breast engorgement. Treatment is administration of antibiotics and continuation of breast-feeding. On occasion, antibiotic therapy is not sufficient to treat mastitis. If a hot, swollen, painful breast does not respond to antibiotics, ultrasound may identify an abscess and guide percutaneous drainage. On mammography, an abscess is a developing asymmetry or mass in a background of breast edema; it does not usually contain gas and is frequently located in the subareolar region (Fig. 10-7A and B). On ultrasound, abscesses are fluid-filled structures with irregular margins in the early phase, but circumscribed margins develop in the later phase as the walls of the abscess form. The abscess may contain debris or multiple septations, which may be drained under ultrasound guidance, but some residua may remain because of thick debris. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous drainage may be curative in small abscesses or palliative until surgical drainage can be performed in large abscesses. Some investigators report using ultrasound-guided aspiration, with abscess irrigation and instillation of antibiotics directly into the abscess cavity, to aid in resolution of the abscess.

Both fibroadenomas and lactating adenomas are solid benign tumors diagnosed during pregnancy. Growth of preexisting fibroadenomas may be stimulated by the elevated hormone levels of pregnancy, and the fibroadenoma may become clinically apparent. Infarction of fibroadenomas has been reported in the literature during pregnancy as well. Presenting as a firm, painless palpable lump that occurs late in prgenancy or during lactation, the lactating adenoma is a circumscribed, lobulated mass containing distended tubules with an epithelial lining. The mass can enlarge rapidly and regress after cessation of lactation. Ultrasound typically shows an oval, well-defined hypoechoic mass that may contain echogenic bands representing the fibrotic bands seen on pathology (see Fig. 10-7C and D). Whether lactating adenoma represents change stimulated by hormonal alterations in a fibroadenoma or tubular adenoma or whether the tumors arise de novo has not been resolved.

A galactocele produces a fluid-filled breast mass that can mimic a benign or malignant solid breast mass. On mammography, a galactocele is a round or oval, circumscribed mass of equal- or low-density (Fig. 10-8A and B). Because a galactocele is filled with milk, the creamy portions of the milk may rise to the nondependent part of the galactocele and produce a rare, but pathognomonic fluid-fluid or fat-fluid appearance on the horizontal beam image (lateral-medial view) at mammography. Ultrasound shows a fluid-filled mass that can have a wide range of sonographic appearances, depending on the relative amount of fluid and solid milk components within it. Galactoceles that are mostly fluid-filled have well-defined margins with thin echogenic walls (see Fig. 10-8C to E). Galactoceles containing more solid components of milk show variable findings, ranging from homogeneous medium-level echoes to heterogeneous contents with fluid clefts. Both distal acoustic enhancement and acoustic shadowing may be seen. The diagnosis is made by an appropriate history of childbirth and lactation, with aspiration yielding milky fluid and leading to resolution of the mass. Aspiration is usually therapeutic.

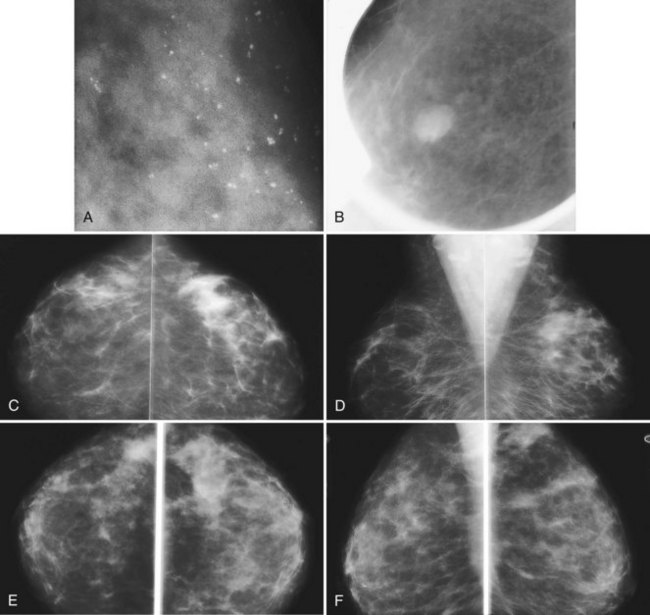

Probably Benign Findings (Bi-Rads® Category 3)

Mammography detects small cancers, but it can also uncover nonpalpable benign-appearing lesions indeterminate for malignancy. Fine-detail diagnostic mammographic views and ultrasound in appropriate cases show that some indeterminate findings are typically benign and the patient can therefore resume screening. Other findings have a low probability (<2%) of malignancy after an appropriate workup that serves as a baseline for follow-up studies (Box 10-5). Sickles, Varas and colleagues, and Yasmeen and colleagues have independently provided data that Breast Imaging Reporting and Database System (BI-RADS®) category 3, or probably benign, findings carry a less than 2% chance of malignancy. Probably benign BI-RADS® category 3 lesions were found in 5%, 3%, and 5% of all screening studies after recall in their series, respectively. Probably benign findings included single or multiple clusters of small, round or oval calcifications; nonpalpable and noncalcified, round or lobulated, circumscribed solid masses; and nonpalpable focal asymmetry containing interspersed fat and concave scalloped margins that resemble fibroglandular tissue at diagnostic evaluation (Fig. 10-9).

Box 10-5

Probably Benign Findings (BI-RADS® Category 3)

Found in 5% of all screening cases after recall and diagnostic workup

Clustered small round or oval calcifications at magnification mammography

Noncalcified oval or lobulated, primarily well-circumscribed solid masses

Asymmetric densities resembling fibroglandular tissue at diagnostic evaluation

From Rosen EL, Baker JA, Soo MS: Malignant lesions initially subjected to short-term mammographic follow-up, Radiology 223:221–228, 2002.

Nipple Discharge and Galactography

The most frequent causes of both nonbloody and bloody nipple discharge are benign conditions. The most common mass producing a bloody nipple discharge is a benign intraductal papilloma, with only approximately 5% of women found to have malignancy at biopsy. The bloody nipple discharge associated with papillomas is due to twisting of the papilloma on its fibrovascular stalk and subsequent infarction and bleeding. Other causes of bloody discharge are cancer, benign findings such as duct hyperplasia/ectasia, and pregnancy as a result of rapidly proliferating breast tissue. Causes of nonbloody nipple discharge are fibrocystic change, medications acting as dopamine receptor blockers or dopamine-depleting drugs, rapid breast growth during adolescence, chronic nipple squeezing, or tumors producing prolactin or prolactin-like substances (Table 10-2).

| Color | Cause |

|---|---|

| Clear or creamy | Duct ectasia |

| Green, white, blue, black | Cysts, duct ectasia |

| Milky | |

| Bloody or blood-related |

The mammogram is frequently negative in the setting of nipple discharge (Table 10-3). Mammographic findings described in association with nipple discharge include a negative mammogram, a single dilated duct in isolation, or a small mass containing calcifications in either papilloma or malignancy (Fig. 10-10A to D). Ultrasound is frequently negative in women with nipple discharge, or fluid-filled dilated ducts without an intraductal mass in the retroareolar region may be seen. Solid masses in a fluid-filled duct may represent debris, a papilloma, or cancer.

Table 10-3 Imaging of Nipple Discharge

| Modality | Finding |

|---|---|

| Mammography | |

| Ultrasound | |

| Galactogram | |

| Magnetic resonance imaging |

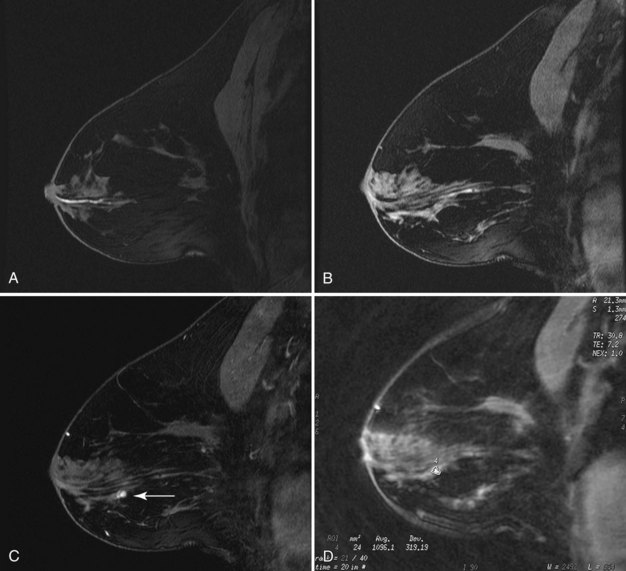

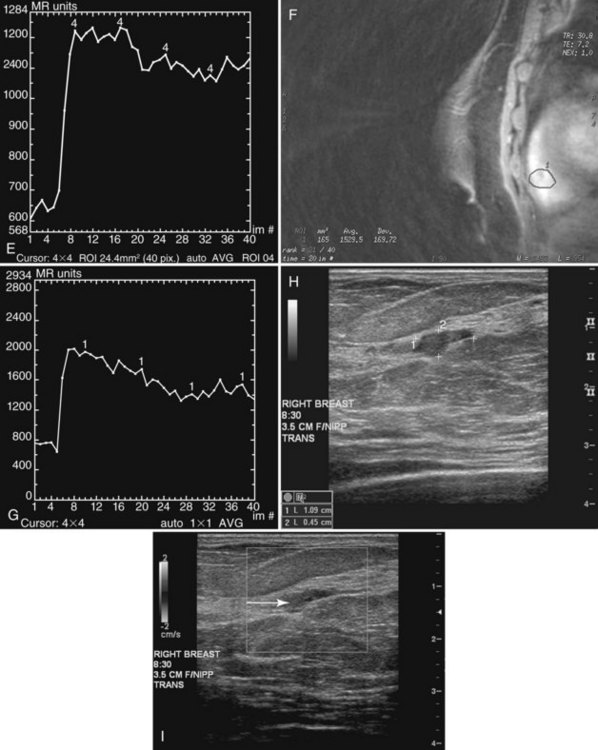

Papillomas on MRI deserve special mention because they mimic cancer by producing a round enhancing mass that frequently has rapid initial early enhancement and a late plateau or washout on kinetic curve analysis, indistinguishable from invasive cancer (Fig. 10-11). For this reason, papillomas are a common cause of false-positive MRI-guided breast biopsies. On MRI, intraductal papillomas can have three patterns. The first pattern is a small circumscribed enhancing mass at the terminus of a dilated breast duct, corresponding to the filling defect seen on galactography. The second pattern is an irregular, rapidly enhancing mass with occasional spiculation or rim enhancement in women without nipple discharge; this is the pattern that cannot be distinguished from invasive breast cancer. Finally, despite the presence of a papilloma, MRI may be negative, with the papilloma undetected on both contrast-enhanced and fat-suppressed T1-weighted studies.

A normal duct arborizes from a single entry point on the nipple into smaller ducts extending over almost an entire quadrant of the breast. Normal ducts are thin and smooth-walled and have no filling defects or wall irregularities (Fig. 10-12A). Ductal ectasia is not uncommon; occasionally, normal cysts or lobules fill from the dilated ducts (see Fig. 10-12B

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree