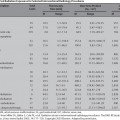

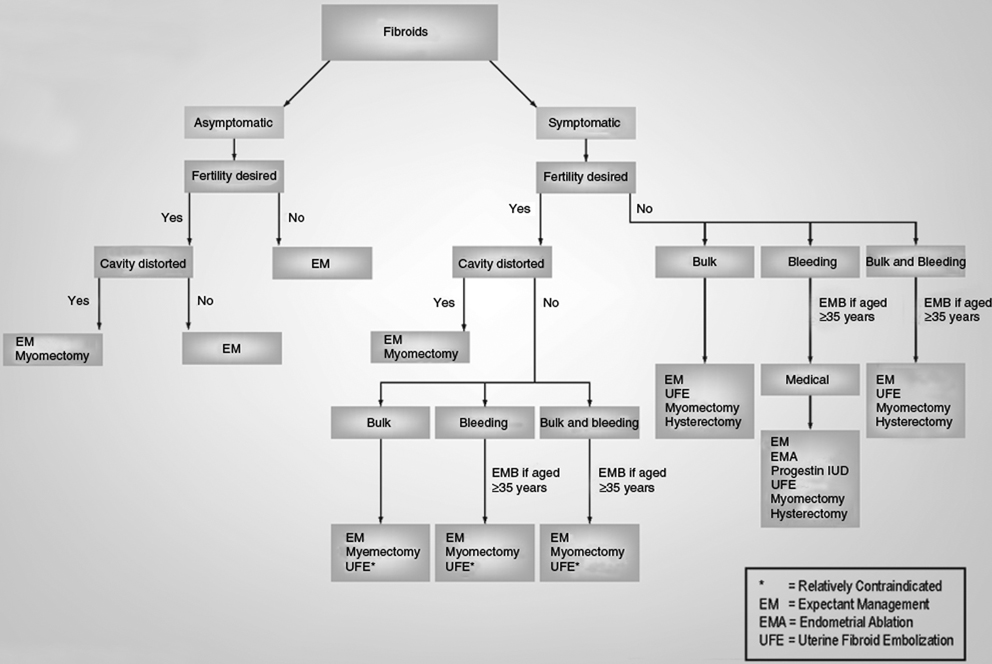

9 Clinical Perspective: Uterine Fibroid Embolization (Gynecology) Jay Goldberg Until the late 1990s, the primary reason for obstetrician/ gynecologists (Ob/Gyns) to involve interventional radiologists (IRs) in the care of their patients was focused in primarily two Ob/Gyn treatment areas: (1) the drainage of pelvic/abdominal fluid collections, and (2) embolization for acute pelvic hemorrhage. The 1995 publication in Lancet authored by Jacque Ravina, M.D., a French gynecologist and colleagues, which presented uterine artery embolization (UAE) as an effective primary fibroid therapy, completely and permanently revolutionized the interventional radiologist’s involvement in women’s health, as well as their relationship with the Ob/Gyn.1 Embolization aimed at stopping bleeding in the acute setting may be a uterine sparing and a potentially life-saving treatment option for both gynecologic and obstetric patients. For gynecologic patients, the most common scenario would be having declining hemoglobin levels in the first 24 hours postoperatively. A specific example might be a woman with delayed arterial bleeding at the cervical stump following hysterectomy. Selective arterial embolization may be preferable to surgical reexploration to both identify the origin of and treat the bleeding. This approach may be especially desirable in the patient with complicated medical conditions, extensive adhesive disease or with bleeding that might be difficult to control surgically, such as in the Space of Retzius following a Burch procedure for urinary incontinence. Postcesarean delivery patients may similarly benefit from selective embolization in the same clinical situation of declining hemoglobin levels thought to be due to arterial bleeding soon following delivery. The more common scenario when embolization might be considered in obstetrics is the patient with an immediate postpartum uterine hemorrhage following vaginal delivery. This is usually caused by uterine atony that has been nonresponsive to the usual interventions of uterine massage, uterotonic medications (pitocin, carboprost tromethamine, misoprostol, and/or methylergonovine), and possibly uterine curettage. Rather than directly proceeding to laparotomy for the specific purpose of obtaining surgical access for uterine artery ligation, uterine compression suturing (B-Lynch), hypogastric artery ligation (rarely performed and not currently a recommended intervention), or hysterectomy, the obstetrician may attempt uterine packing followed by UAE. The uterus is tightly packed with gauze, placed transcervically until it hopefully leads to compression that is sufficient to stop or significantly decrease bleeding. A decision must then be made to just observe the patient or to proceed with UAE, during which time blood products might be given, depending upon the hemodynamic stability, estimated blood loss, and starting hematocrit. The goal of embolization of both uterine arteries for such patients would be to decrease overall uterine perfusion and arterial pressure by blocking its major blood supply, hopefully leading to decreased uterine bleeding. Collateral blood supply to the uterus almost always supplies perfusion sufficient to prevent uterine necrosis. In theory, embolization of the uterine arteries in the postpartum patient bleeding from a nonresponsive uterine atony sounds like a better option than laparotomy and vessel ligation or hysterectomy. However, there are several factors that may limit its clinical effectiveness and practicality. Most obstetrical areas do not have the fluoroscopy equipment necessary for embolization, requiring an often hemodynamically unstable patient to be transferred to another area of the hospital. If the patient becomes more unstable during transport or in the radiology suite, a potential disaster could occur. Additionally, with most births occurring after usual work hours or on weekends, an IR may not be readily available, delaying the embolization. Also, in cases of postpartum uterine atony not responding to embolization attempt, surgical intervention has been further delayed with additional blood loss, putting the woman at greater risk for disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC), hemorrhagic shock, and death. Patients that are hemodynamically unstable are usually best served by being quickly taken to the operating room. However, not all patients are candidates for this type of intervention. Most IRs prefer the patient to have an international normalized ratio (INR) <2, often requiring time to sufficiently replace blood products. Even in postpartum patients with bleeding successfully abated following bilateral uterine artery embolization, there may be significant morbidity, including the risk of complete uterine necrosis. The majority of patients stable enough for the time required to transfer them to the radiology suite and for the embolization procedure would probably have been sufficiently treated with uterine packing and blood transfusion alone. Obviously, it would be impossible to have the power sufficient for a randomized trial assessing the added benefit of UAE added to uterine packing in severe postpartum uterine atony. One final consideration for the Ob/Gyn is that a patient who requires an exploratory laparotomy to correct a surgical complication will be much more likely to file a lawsuit than one whose condition was effectively treated by minimally invasive transcutaneous or transvaginal techniques performed by an IR. This is another reason why embolization in this setting has become an increasingly accepted option for treatment. Uterine fibroids are the most common tumors of the female reproductive tract, occurring in 20 to 70% of women between the ages 30 to 50 years. Black women are most frequently affected, whereas white women, Asians, and Scandinavians have lower incidences. Tumor size varies widely and many women have multiple fibroids. Patients may be asymptomatic with diagnosis on palpation of a firm, enlarged uterus on routine examination or on an incidental finding at imaging. Others may present symptoms such as menorrhagia, intermenstrual bleeding, pelvic pain/pressure, dyspareunia, urinary frequency, abdominal distension, infertility, and pregnancy complications. Given the nature and severity of these symptoms, fibroids can have a significant impact on quality of life.2 Most symptomatic women eventually seek medical treatment. There are many fibroid treatments available, their selection based on many factors, including bulk symptoms, bleeding symptoms, and desire for future fertility/ uterine preservation (Fig. 9.1). Medications used to treat fibroids include analgesics, usually nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and combination estrogen/progestin oral contraceptives (OCPs). Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists (e.g., leuprolide) can temporarily reduce fibroid volume by up to 40% while also decreasing vaginal bleeding.3 However, their significant side-effect profile (e.g., vasomotor instability, mood swings, bone loss) and the fibroids’ quick return to baseline upon discontinuation of therapy primarily restrict use to temporary tumor reduction prior to surgery. Fig. 9.1 Algorithm for the treatment of uterine fibroids. (Image courtesy of Jefferson Fibroid Center, www.jeffersonhospital.org/fibroid)

Embolization for Indications Other Than Uterine Fibroids

Uterine Fibroid Embolization

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree