Diagnosis of CNS viral infections is challenging; yet, significant progress in laboratory diagnosis of CNS infections has come through applications of serology and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to CSF and tissues. Advances in molecular and laboratory techniques, together with neuroimaging, epidemiologic, and surveillance efforts, are yielding greater success in CNS viral diagnosis and treatment.

Some viruses, such as herpes simplex and rabies, specifically target the brain; for hundreds of others, the central nervous system (CNS) is an unusual but potentially devastating site of involvement. The pathogens range from common to rare, acute to chronic, and mild to fatal ( Table 1 ). Signs of primary infection vary from subclinical infection, detected only by the presence of antibodies, to systemic febrile illnesses with nervous system symptoms (headache, lethargy, photophobia) or frank meningeal or parenchymal CNS disease.

| Family | Genus | Virus or vernacular name | Abbreviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Herpesviridae | Human herpesvirus | Herpes simplex virus-1 (or Human herpesvirus 1) | HSV-1 |

| Herpes simplex virus-2 (or Human herpesvirus 2) | HSV-2 | ||

| Varicella-zoster virus | VZV | ||

| Epstein-Barr virus | EBV | ||

| Cytomegalovirus | CMV | ||

| Human herpesvirus 6 | HHV-6 | ||

| Human herpesvirus 8 | HHV-8 | ||

| Cercopithecine herpesvirus | Simian B virus | B virus | |

| Picornaviridae | Human enterovirus | Poliovirus types 1–3 | Polio |

| Coxsackievirus gp A, gp B | Coxsackie A or B | ||

| Echovirus types 1–33 | Echovirus | ||

| Enterovirus types 70,71 | AHC | ||

| Flaviviridae | Flavivirus | West Nile virus | WNV |

| Japanese encephalitis virus | JE | ||

| St. Louis encephalitis | SLE | ||

| Murray Valley encephalitis | Murray Valley | ||

| Kunjin | Kunjin | ||

| Tick-borne encephalitis (Central European encephalitis) | TBE-W | ||

| Tick-borne encephalitis (Far Eastern encephalitis) | TBE-FE | ||

| Powassan | POW | ||

| Louping III virus | Louping Ill | ||

| Kyasanur Forest virus | Kyasanur Forest | ||

| Modoc virus | Modoc virus | ||

| Rocio virus | Rocio | ||

| Dengue type 1–4 | Dengue | ||

| Hepacivirus | Hepatitis C virus | HCV | |

| Togaviridae | Alphavirus | Eastern Equine Encephalitis virus | EEE |

| Western Equine Encephalitis virus | WEE | ||

| Venezuelan Equine Encephalitis | VEE | ||

| Everglades | EVE | ||

| Semliki Forest virus | SF | ||

| Me Tri virus | Me Tri | ||

| Rubivirus | Rubella (German measles) | Rubella | |

| Bunyaviridae | Bunyavirus | California serogroup (includes California encephalitis, La Crosse, Jamestown Canyon, Snowshoe Hare in US and relatives: Tahyna, Batai, Inkoo in Europe) | California serogroup |

| Phlebovirus | Rift Valley Fever virus | Rift Valley Fever | |

| Toscana virus | Toscana | ||

| Rhabdoviridae | Lyssavirus | Rabies | Rabies |

| Australian bat lyssavirus | |||

| Vesiculovirus | Chandipura virus | Chandipura | |

| Paramyxoviridae | Morbillivirus | Measles | Measles |

| Unclassified | Hendra | Hendra | |

| Nipah | Nipah | ||

| Rubulavirius | Mumps | Mumps | |

| Respirovirus | Human Parainfluenza | Parainfluenza | |

| Orthomyxoviridae | Influenza A virus | Influenza A | Flu A |

| Influenza B virus | Influenza B | Flu B | |

| Retroviridae | Lentivirus | Human immunodeficiency virus 1 | HIV-1 |

| Human Immunodeficiency virus 2 | HIV-2 | ||

| Deltaretrovirus | Human T-lymphotropic virus 1 | HTLV-1 | |

| Human T-lymphotropic virus 2 | HTLV-2 | ||

| Polyomaviridae | Human polyomavirus (formerly papavovirus) | JC virus (agent of PML) | JCV |

| BK virus | BKV | ||

| Arenaviridae | Arenavirus | Lymphocytic choriomeningitis | LCMV |

| Lassa Fever virus | Lassa Fever | ||

| Junin virus | Argentine Hem. Fever | ||

| Machupo virus | Bolivian Hem. Fever | ||

| Parvoviridae | Parvovirus | Parvovirus B19 | Fifth disease |

| Poxviridae | Orthopoxvirus | Variola virus | Smallpox |

| Vaccinia virus | |||

| Monkeypox virus | Monkeypox | ||

| Reoviridae | Coltivirus | Colorado Tick Fever virus | CTFV |

| Eyach virus | Eyach | ||

| Seadornavirus | Banna virus | BAV | |

| Rotavirus | Rotavirus | Rotavirus | |

| Adenoviridae | Adenovirus | Adenovirus (serotypes 7, 12, 32) | Adenovirus |

Viral meningitis, an inflammatory response to viral infection of leptomeningeal cells and subarachnoid space, is characterized by fever, headache, photophobia, stiff neck, mild lethargy, or drowsiness. The presence of more severe alterations in consciousness, such as confusion, behavior disorders, stupor, or coma, leads to consideration of other diagnoses. Viral encephalitis, the manifestation of brain parenchymal viral infection, may be diffuse or focal. In diffuse encephalitis, altered mental status and seizures are early signs of disease. Focal findings, such as aphasia, visual disturbances, hemiparesis, movement disorders, or ataxia, if present, reflect predilection of some viruses for specific brain regions or cell types. Many patients with encephalitis also have associated meningitis (meningoencephalitis) and, in some cases, involvement of spinal cord or nerve roots (encephalomyelitis, encephalomyeloradiculitis). On the other hand, some viruses (rabies, simian B virus) produce encephalitis without meningeal involvement.

Diagnosis of CNS viral infections is challenging for several reasons. The physical findings may be nonspecific, ie, the basic clinical features of most types of viral meningitis or encephalitis are similar. Host factors can influence the clinical phenotype, with the same organism causing meningitis in a normal host also causing encephalitis or complex syndromes in immunocompromised patients. Rapid diagnostic tests are available for some but not all viruses. The sensitivity and specificity of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is equivalent to serology for some viruses (West Nile virus [WNV]). Serology may show cross reactivity with related viruses. Culture diagnosis can be difficult, time-consuming, or unavailable. Time is critical because it is the brain.

Diagnostic decision making begins with a detailed history, with attention to recent travel, insect or animal bites, immunizations, occupational or other potential exposures, or immunosuppression. Then, physical examination findings, neurologic findings, laboratory tests, and imaging studies produce further guidance and support. The physician uses clinical, imaging, and laboratory studies to narrow the field, paying particular attention to diagnoses for which agent-specific treatment is available.

Physical examination aids to diagnosis

Specific physical examination features provide clues to the diagnosis of individual viruses. Viral exanthems are helpful when they occur. Vesicular eruptions occur at sites of inoculation of herpes simplex viruses and in dermatomal distribution when latent varicella zoster virus reactivates. “Hand, foot, and mouth disease” with vesicles on palms, soles, and buttocks, signifies enterovirus infection. Maculopapular rashes occur with EBV after ampicillin treatment; as “roseola” with human herpes virus-6 (HHV-6); and in Colorado Tick fever (CTF). A maculopapular rash beginning on the face/chest and extending downward is measles. Confluent erythema over the cheeks or distal purpura is seen with parvovirus .

Respiratory, ocular, cardiovascular, or systemic signs and symptoms point to additional diagnoses. Pharyngitis occurs with adenovirus or enterovirus (as “herpangina” or vesicles on the soft palate). Conjunctivitis is seen with adenovirus, enterovirus, or St. Louis encephalitis (SLE); and retinitis with cytomegalovirus (CMV), WNV, measles, rubella. Parotitis is associated with mumps or lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV); orchitis with mumps, LCMV, or EBV; and lymphadenopathy with mumps or LCMV. Pneumonia is caused by influenza and parainfluenza; and myocarditis/pericarditis by enteroviruses, and gastroenteritis with rotavirus. Arthritis is associated with LCMV or parvovirus infections; myalgias with arboviruses; mononucleosis syndromes with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) or CMV . High viremias typical of arboviruses cause “fever-arthralgia-rash” syndrome of WNV, CTF, Toscana (TOS), and Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus (VEE).

Neurologic aids to diagnosis

Besides the fever and signs of meningeal involvement characteristic of meningitis, patients with encephalitis will have evidence of either diffuse or focal brain involvement. Patients with encephalitis commonly have confusion, behavioral changes, or altered level of consciousness. Furthermore, every possible type of focal neurologic disturbance has been described in viral encephalitis. Specific signs and symptoms reflect sites of infection, inflammation, and injury.

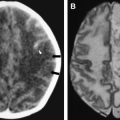

Focal findings commonly encountered include aphasia, hemiparesis, ataxia, hyperkinetic or parkinsonian movement disorders, and cranial nerve deficits. Focal examination findings in a patient with encephalitis raises the possibility of herpes simplex virus type-1 (HSV-1) encephalitis ( Fig. 1 ) and necessitates neuroimaging studies to exclude brain abscess, subdural empyema, cranial extradural abscess, septic venous thrombosis, or infectious vasculitis with ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke and establish the safety of proceeding with the lumbar puncture. In cases with apparent involvement of spinal cord and/or nerve roots (encephalomyelitis, encephalomyeloradiculitis), spine MRI is performed to exclude compressive lesions.

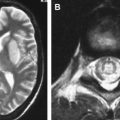

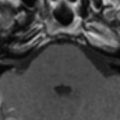

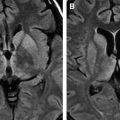

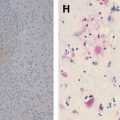

HSV-1, accounting for 10% to 20% of viral infections of the CNS in the United States , is a common etiologic agent of focal viral encephalitis in North America. Japanese encephalitis (JE) virus is the most common cause of focal viral encephalitis in Asia ( Fig. 2 ) where there are 30,000 to 50,000 cases and 10,000 deaths from Japanese encephalitis each year . Other viruses causing focal encephalitis are WNV, St. Louis encephalitis virus ( Fig. 3 ), varicella zoster virus (VZV) ( Fig. 4 ), HHV-6, EBV, enteroviruses, Powassan’s virus, La Crosse virus, the equine encephalitis viruses, measles, Nipah virus, tick-borne encephalitis (TBE) viruses, and Influenza A .

Despite a large number of candidate viruses, a more limited group of viruses is responsible for most cases in which a specific cause is identified. In the United States, the most common causes of acute aseptic (viral) meningitis in both adults and children are enteroviruses and the most common causes of viral encephalitis are herpes simplex virus and arboviruses . Seasonal and geographic predilections for arboviruses and enteroviruses can be useful in their diagnoses. Arbovirus and enterovirus infections occur predominantly in summer, sometimes as classical seasonal epidemics. CMV, EBV, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), VZV, and measles are less common, and other causes are rare. The less frequent pathogens may be associated with immunodeficiency, and testing for additional viruses is justified in these patients. Animal exposure or occupational data raise the possibility of other rare causes of meningitis and encephalitis: herpes (simian) B virus, LCMV, or rabies. Worldwide, there are tens of thousands of deaths from rabies each year . The more common causes of myelitis or motor neuronitis in the United States are WNV, the nonpolio enteroviruses, and HSV-2. Lumbosacral radiculitis without myelitis also occurs with HSV-2 and WNV ( Fig. 5 ).

Another form of encephalitis not due to direct viral infection of brain parenchyma but instead due to an alteration of normal immune function following recent viral infection or vaccination is acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) ( Fig. 6 ). It is a monophasic demyelinating syndrome characterized by rapid development of focal or multifocal neurologic dysfunction and may follow vaccination or acute viral illness by 1 to 3 weeks. Postinfectious encephalomyelitis followed an estimated 1 in 1000 cases of measles, usually within 2 weeks of the rash . Before introduction of non-neural human diploid cell vaccine against rabies, postvaccination encephalomyelitis was estimated at 1 per 3,000 to 35,000 recipients for vaccinations prepared in rabbit brain or 1 per 25,000 recipients of duck embryo rabies vaccine . After primary smallpox vaccination, ADEM rates were reported as 1 in 4000 to 1 in 80,000 and after revaccination, from 1 in 50,000 to 1 in 450,000 . The clinical signs and symptoms—sudden fever, seizures, loss of consciousness, or focal deficits—can be identical to acute viral encephalitis. The onset of postinfectious or postvaccination disease is usually more abrupt and the ADEM patient need not be febrile.

Neurologic aids to diagnosis

Besides the fever and signs of meningeal involvement characteristic of meningitis, patients with encephalitis will have evidence of either diffuse or focal brain involvement. Patients with encephalitis commonly have confusion, behavioral changes, or altered level of consciousness. Furthermore, every possible type of focal neurologic disturbance has been described in viral encephalitis. Specific signs and symptoms reflect sites of infection, inflammation, and injury.

Focal findings commonly encountered include aphasia, hemiparesis, ataxia, hyperkinetic or parkinsonian movement disorders, and cranial nerve deficits. Focal examination findings in a patient with encephalitis raises the possibility of herpes simplex virus type-1 (HSV-1) encephalitis ( Fig. 1 ) and necessitates neuroimaging studies to exclude brain abscess, subdural empyema, cranial extradural abscess, septic venous thrombosis, or infectious vasculitis with ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke and establish the safety of proceeding with the lumbar puncture. In cases with apparent involvement of spinal cord and/or nerve roots (encephalomyelitis, encephalomyeloradiculitis), spine MRI is performed to exclude compressive lesions.

HSV-1, accounting for 10% to 20% of viral infections of the CNS in the United States , is a common etiologic agent of focal viral encephalitis in North America. Japanese encephalitis (JE) virus is the most common cause of focal viral encephalitis in Asia ( Fig. 2 ) where there are 30,000 to 50,000 cases and 10,000 deaths from Japanese encephalitis each year . Other viruses causing focal encephalitis are WNV, St. Louis encephalitis virus ( Fig. 3 ), varicella zoster virus (VZV) ( Fig. 4 ), HHV-6, EBV, enteroviruses, Powassan’s virus, La Crosse virus, the equine encephalitis viruses, measles, Nipah virus, tick-borne encephalitis (TBE) viruses, and Influenza A .

Despite a large number of candidate viruses, a more limited group of viruses is responsible for most cases in which a specific cause is identified. In the United States, the most common causes of acute aseptic (viral) meningitis in both adults and children are enteroviruses and the most common causes of viral encephalitis are herpes simplex virus and arboviruses . Seasonal and geographic predilections for arboviruses and enteroviruses can be useful in their diagnoses. Arbovirus and enterovirus infections occur predominantly in summer, sometimes as classical seasonal epidemics. CMV, EBV, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), VZV, and measles are less common, and other causes are rare. The less frequent pathogens may be associated with immunodeficiency, and testing for additional viruses is justified in these patients. Animal exposure or occupational data raise the possibility of other rare causes of meningitis and encephalitis: herpes (simian) B virus, LCMV, or rabies. Worldwide, there are tens of thousands of deaths from rabies each year . The more common causes of myelitis or motor neuronitis in the United States are WNV, the nonpolio enteroviruses, and HSV-2. Lumbosacral radiculitis without myelitis also occurs with HSV-2 and WNV ( Fig. 5 ).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree