Fig. 17.1

Contrast-enhanced voiding urosonography (ceVUS): Pre- (a) and post-intravesical (b) administration of ultrasound contrast agent. A duplex kidney on the right with reflux of the ultrasound contrast agent into the upper moiety (arrow). (Courtesy of Kassa Darge, MD, PhD, CHOP, Philadelphia, USA)

Since the late 1990s, ceVUS has gained widespread acceptance to diagnose VUR in Europe. Using intravesically administered microbubbles, ceVUS can also monitor the filling and voiding functions without harmful radiation. VUR and even infrarenal reflux can be clearly visualized (Figs. 17.2a–c, 17.3). Several recent papers show that transperineal ultrasound during voiding allows for reliable assessment of urethral pathology, indicating that this early restriction for ceVUS has been overcome [23].

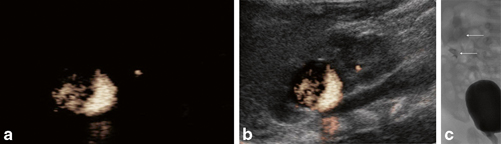

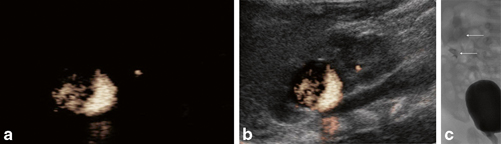

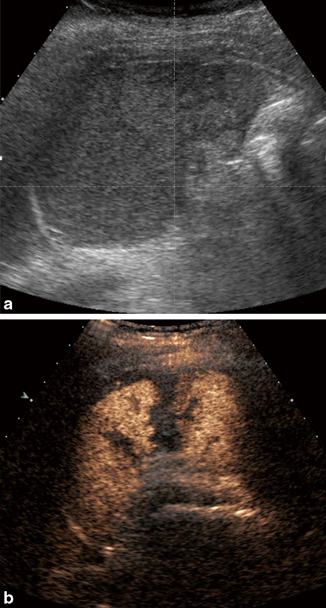

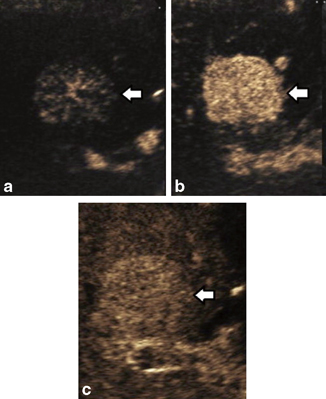

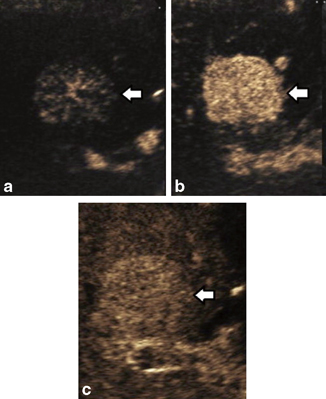

Fig. 17.2

Contrast-enhanced voiding urosonography (ceVUS; a and b): Images of the right duplex kidney after intravesical administration of ultrasound contrast agent. The scan is a dedicated contrast-specific modality showing a duplex kidney on the right with reflux in both, the upper and lower moieties. For comparison, the voiding cystourethrography (VCUG; c) also demonstrates reflux in both moieties in the same patient. (Courtesy of Kassa Darge, MD, PhD, CHOP, Philadelphia, USA)

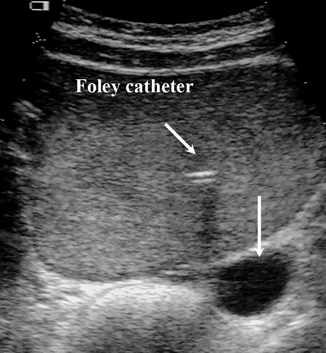

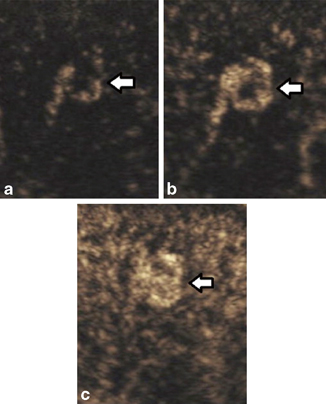

Fig. 17.3

Contrast-enhanced voiding urosonography (ceVUS): the bladder is filled with echogenic ultrasound contrast agent. The left terminal ureter is dilated (arrow). However, there is no reflux of microbubbles into the left ureter. (Courtesy of Kassa Darge, MD, PhD, CHOP, Philadelphia, USA)

The most recent meta-analysis of all the comparative studies of ceVUS with VCUG and DRNC in children included more than 2300 children with more than 4600 pelvi-ureteric units. Using VCUG as the reference method, ceVUS had a sensitivity of 90 % and a specificity of 92 %.

High correlation of reflux grading between the two methods was noticed. Severe and higher-grade VUR is more commonly detected on ceVUS as compared to VCUG [1].

The combination of contrast-enhanced urethrosonography with ceVUS has enabled exquisite depiction of urethral pathologies, including posterior urethral valves [24]. The visualization of intrarenal reflux is easier with ceVUS [15, 25–27].

Promoted by the Uroradiology Task Force of the European Society of Paediatric Radiology (http://www.espr.org/taskforce/uroradiology/), VCUG and DRNC are increasingly being replaced with ceVUS in European pediatric radiology centers.

Abdominal Trauma

Abdominal ultrasound is commonly used to evaluate blunt abdominal trauma. However, the technique is unreliable for the detection of parenchymal lesions, and intravenous contrast CT imaging remains the mainstay for evaluating serious blunt abdominal trauma in hemodynamically stable patients. Three case reports with four patients are available where pancreatic, hepatic, and splenic injuries were missed on ultrasound alone. In all cases, CEUS correctly identified the organ laceration (Fig. 17.4a, b) [28–30]. Valentino et al. [31] reviewed their experience with CEUS for solid organ injuries in 12 children with seven splenic, four liver, one right adrenal gland, and one pancreatic injury as well as 15 children with negative abdominal CT scans. CEUS detected 13 of the 14 lesions with an overall sensitivity and specificity of 92.2 and 93.8 %, respectively (100 % positive and negative predictive values), but missed the right adrenal contusion. In comparison, regular abdominal ultrasound posted a sensitivity and specificity of 57.1 and 68.4 %, respectively. With its improved accuracy, the authors consider CEUS a useful alternative to contrast CT scan for stable abdominal trauma, thus potentially eliminating exposure to radiation.

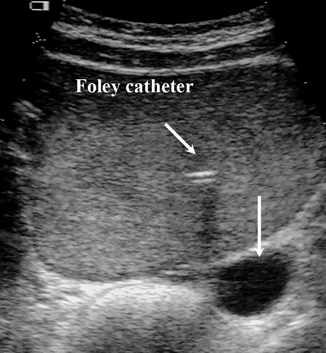

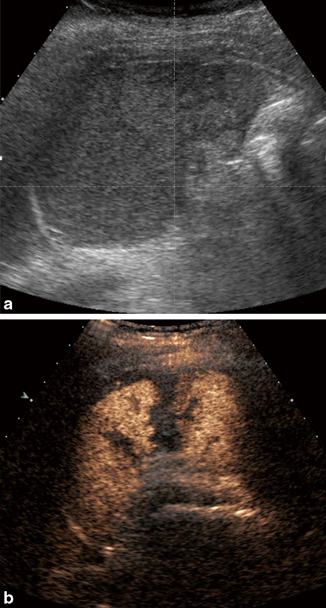

Fig. 17.4

a and b Contrast-enhanced ultrasound for blunt abdominal trauma. The spleen pre- and post-intravenous ultrasound contrast administration. On the gray scale image, it is difficult to appreciate any laceration of the spleen. However, with intravenous contrast using contrast-specific ultrasound modality, the splenic laceration is clearly depicted. (Courtesy of Kassa Darge, MD, PhD, CHOP, Philadelphia, USA)

Menichini et al. [32] retrospectively looked at 73 stable children with abdominal trauma . CT identified 67 lesions to the liver, spleen , and kidneys. CEUS sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy were each 100 %, in difference to ultrasound (38.8, 100, and 44 %, respectively). CEUS identified parenchymal active bleeding in eight cases and partial devascularization in one case. With contrast CT scan, eight additional patients with active parenchymal hemorrhage, two with vascular bleeding, and two with urinoma were identified. The authors conclude that CEUS is almost as sensitive as contrast CT scan to pick up solid organ lesions, but CT scan remains more sensitive and accurate identifying prognostic indicators such as active bleeding and urinoma.

CEUS is considered only part of the trauma algorithm in low-energy trauma in hemodynamically stable patients. Drawbacks include operator competence and reduced panoramic view. Diaphragmatic ruptures and bowel and mesenteric injuries may be missed. CEUS may be valuable for follow-up of solid organ injuries managed nonoperatively, especially in children and pregnant women [33, 34].

Liver Imaging

CEUS offers several advantages over other imaging modalities in evaluation of focal liver lesions. It provides real-time dynamic imaging, permitting visualization of enhancement during the very early or late phases of contrast enhancement. CEUS can demonstrate a clear and consistent washout phase useful to characterize malignant lesions and differentiate benign nodules (Figs. 17.5a–c, 17.6a–c). SonoVue, approved for liver scans in adults in numerous countries (not USA), can be used in patients with renal impairment considered not appropriate candidates for CT or MRI [15].

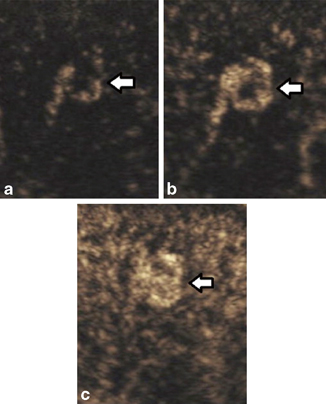

Fig. 17.5

A young man with a hepatic hemangioma. Three sequential CEUS images of the same liver mass (arrows). a Early peripheral nodular enhancement. b Progressive centripetal contrast enhancement. c Near-complete enhancement of the hemangioma. (From [6], with permission from Elsevier, license number 3636550696548)

Fig. 17.6

A young woman with focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH). Three sequential CEUS images of the same liver lesion (arrows). a Early hypervascular enhancement within the central scar. b Progressive centrifugal direction of contrast enhancement. c Sustained mild enhancement on the portal venous phase. (From [6], with permission from Elsevier, license number 3636550696548)

There are abundant well-designed studies in the adult literature available, but reports in children remain scarce. There are two single case reports in teenagers where CEUS aided in the diagnosis of rare liver tumors, a primary gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the liver and a fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma [35, 36].

Working at a pediatric liver center, Jacob et al. [37] reviewed 44 children referred for CEUS assessment of a gray scale sonographic indeterminate focal liver lesion over a 5-year period. CEUS examination was compared to consensus interpretation of other imaging and histology. In 29 of 34 cases (85.3 %), reference imaging agreed to CEUS. In the five discordant cases, reference imaging showed no abnormality (four fatty changes and one regenerative nodule on CEUS). In ten cases, no other imaging was performed and histology (seven cases) or follow-up sonography (three cases) confirmed the diagnosis. In one case, all imaging methods were consistent with a malignant lesion, but histology showed a benign hepatocellular adenoma. The specificity of CEUS was 98 % and the negative predictive value 100 %. The authors conclude that CEUS compares favorably with CT scan or MRI to differentiate indeterminate gray scale sonographic liver lesions in children. CEUS could become an important diagnostic tool to reliably characterize focal liver tumors and to avoid radiation, at least in higher-volume pediatric liver centers such as the Pediatric Liver Unit at King’s College Hospital, London, UK.

Bonini et al. [38] reviewed 44 liver transplants performed in 40 patients over a 1-year period. In 30 patients, clinical or sonographic signs were suggestive of possible vascular or biliary complications. In all these patients, a second duplex ultrasound with intravenous contrast (SonoVue) was performed. A total of 14 vascular complications were confirmed with CT, angiography, or percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography. CEUS correctly identified four of five cases of hepatic artery thrombosis and all cases of thrombosis involving the portal vein (six) and the hepatic veins (three). It failed to identify one case of hepatic artery thrombosis characterized by collateral circulation arising from the phrenic artery and the single case of hepatic artery stenosis, which was more evident on color Doppler showing a typical tardus parvus waveform. There was also one extensive splenic infarct that was visualized only after infusion of the contrast agent. While biliary leaks were better visualized, the contrast enhancement did not provide any particular diagnostic advantage.

The authors conclude that CEUS improves diagnostic confidence and may reduce the need for more invasive imaging studies in the postoperative follow-up of pediatric liver transplant recipients. CEUS allows accurate assessment of graft vascularization with clear distinction between normally vascularized and hypoperfused areas of the parenchyma and improved visualization of peri-graft collections/leaks as well as bile duct dilatation secondary to anastomotic stenosis.

Other Applications

Other reports about CEUS use in children are rare. Several case reports have been published describing the utility of CEUS to follow up ovarian torsion [39], characterize solid pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas [40], and diagnose internal iliac vein thrombosis [41] as well as intracardiac masses [42]. Riccabona et al. [43] report on preoperative applications of CEUS for kidney transplants.

Pediatric CEUS may be useful to evaluate femoral head perfusion, arthritis assessment, testicular/ovarian torsion, pyelonephritis, and inflammatory bowel disease [44]. CEUS offers promising applications in pediatric oncology . McCarville et al. [45] from St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis/TN reported their initial experience in 13 children with CEUS for evaluation of malignant pediatric abdominal and pelvic solid tumors . Post-contrast ultrasound inter-reviewer agreement improved slightly for detection of tumor margins, local tumor invasion, and associated adenopathy.

Two abstracts presented at the Euroson 2013 meeting reported on the initial experience of other centers with CEUS for solid abdominal tumors. Batko et al. [46] presented their experience with 15 children and noted that CEUS examination may be useful for initial diagnosis as well as treatment monitoring of solid abdominal tumors to allow for reduction of imaging with ionizing radiation.