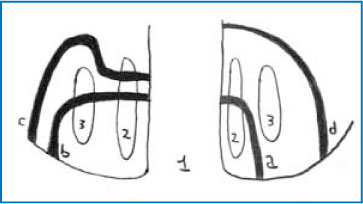

Fig. 6.1

Goodsall’s Law

Worldwide, cryptoglandular infection is considered the most likely cause of cryptogenic anal fistula. Most people have between six and eight anal glands, varying in location between the internal anal sphincter and the intersphincteric groove. The sequence of events leading to fistula formation and its consequences is usually described as obstruction-infection-abscess-fistula. Thus, an obstruction of the gland causes an infection which in turn produces an abscess and then a fistula. However, about 10% of abscesses are due to other causes, such as Crohn’s disease, HIV infection, trauma, sexually transmitted diseases, and radiation therapy [1–4].

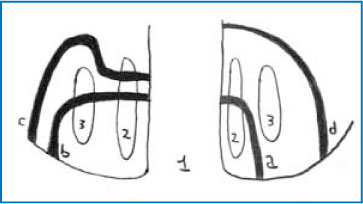

Fistulas were classified by Parks and colleagues into different types according to their relation to the anal sphincter muscles (Fig. 6.2).

Intersphincteric fistulas pass through internal sphincter (45% of cases) (Fig. 6.2).

Transsphincteric fistulas pass through both the internal and external sphincter (30% of cases) (Fig. 6.2).

Suprasphincteric fistulas pass through the internal sphincter but traverse the external sphincter below the puborectalis muscle (20% of cases) (Fig. 6.2).

Extrasphincteric fistulas pass the sphincter complex through the ischiorectal fossa to the perianal skin (5% of cases).

Fig 6.2

The Parks classification. 1 Rectum, 2 internal sphincter, 3 external sphincter, a intersphincteric, b extrasphincteric, c suprasphincteric, d transsphincteric

This classification is not an abstract one but is genuinely useful as it can predict the risk of fecal incontinence after surgery [5].

Fistulas can also be classified as simple or complex, even if there is no consensus in the literature. Simple fistulas may include submucosal, low transsphincteric, and low intersphincteric fistulas (traversing < 30% of the internal anal sphincter). Complex fistulas tend to be those with multiple external openings, high transsphincteric, suprasphincteric, and extrasphinc- teric fistulas, high blind extensions, horseshoe tracts, anterior fistulas in female patients, fistulas associated with a high risk of continence disturbance after surgery, and fistulas in Crohn’s disease or associated with irradiation.

The great challenges in the treatment of anal fistulas are maintaining continence, achieving rapid healing, the elimination of all septic foci, and reducing the risk of recurrence.

6.2 Surgical Approaches to Fistula Treatment

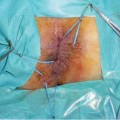

Medical therapy is not useful for the treatment of anal fistulas even if antibiotic prophylaxis and infliximab may have a therapeutic roles especially in patients with Crohn’s disease. Surgical treatment achieves the highest number of fistula closures and is based on several different procedures: fistulotomy, fistulectomy, seton (cutting and non-cutting types), endorectal advancement flaps, fibrin glue, plugs, ligation of fistula tract (LIFT), and video-assisted anal fistula treatment (VAAFT). Before a patient undergoes a surgical procedure, it is important to evaluate the relevance of the problem. This can be performed in two steps: outside the operating theatre, with preoperative examination, and inside the operating theatre, by identifying both orifices of the fistula.

Endosonography is a safe procedure that allows the detection of abnormalities in the anal canal as well as defects of the perianal region, including the fistula tract and abscesses. Moreover, it can identify a fistula as simple or complex. However, it is not always easy to differentiate pathological findings from scars or granulating tracts. Consequently, hydrogen peroxide injection from the external orifice of the fistula, so as to create a gaseous contrast, has been introduced. Another important innovation is 3D axial reconstruction, which generates a multidimensional view of the pathological findings.

MRI is used if initial attempts to determine the internal orifice of the fistula are unsuccessful. It provides better visualization not only of the fistula itself but also of the anatomy of the perineum and of the relationship between the fistula and other organs. Fistulography is a radiological technique that uses X- rays and a water-soluble contrast to demonstrate the fistula tract. Unfortunately, it cannot show the relationship between the fistula and the perineum and is therefore useful only in rare cases. The function of the anal sphincter can be evaluated with anal manometry, which allows the surgeon to choose the best surgical technique [6–8].