Diseases that cause a decrease in lung density result in increased radiolucency (hyperlucency) on chest radiography and decreased attenuation on computed tomography (CT). Decreased lung density may result from obstructive overinflation without lung destruction (e.g., asthma, constrictive bronchiolitis), overinflation with lung destruction (e.g., emphysema), or a reduction in the quantity of blood and tissue in the absence of pulmonary overinflation (e.g., Swyer-James-McLeod syndrome, pulmonary thromboembolism).

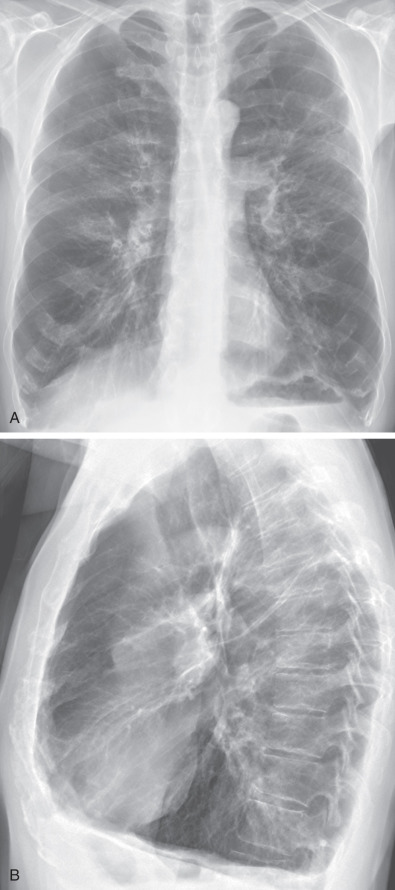

It is important to keep in mind that unilateral hyperlucency on a chest radiograph may also result from pneumothorax, patient rotation, and congenital and acquired abnormalities of the chest wall (e.g., congenital absence of the pectoral muscles and mastectomy). In fact, patient rotation and chest wall abnormalities, in particular, mastectomy, are the most common causes of unilateral hyperlucent lung on chest radiography ( Fig. 6.1 ). Patient rotation is observed in up to 1% of all chest radiographs and may cause an apparent unilateral hyperlucent lung. The hyperlucency always occurs on the side to which the patient rotates and is secondary to asymmetric absorption of the x-ray beam by the chest wall.

Alteration in Pulmonary Volume

General Excess of Air

Lung diseases that cause decreased density are characterized by overinflation, with the exception of proximal interruption (absence) of the pulmonary artery, unilateral hyperlucent lung (Swyer-James-McLeod syndrome), partly obstructing endobronchial lesions, and pulmonary thromboembolism without infarction.

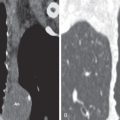

Radiologic signs that may be observed in association with a general increase in intrapulmonary air relate to the diaphragm, the retrosternal space, and the cardiovascular silhouette, the most important of which are signs related to the diaphragm. In patients who have severe emphysema, the diaphragm is depressed, often to the level of the 7th rib anteriorly and the 11th interspace or 12th rib posteriorly; the normal dome configuration is flattened, and there may be blunting of the posterior costophrenic angle as seen on the lateral chest radiograph ( Fig. 6.2 ). Although such flattening is often evaluated subjectively, direct measurement is more accurate. Flattening of the diaphragm is best assessed on a lateral chest radiograph by drawing a straight line from the sternophrenic junction to the posterior costophrenic junction. The dome of the hemidiaphragm should be 2.6 cm or more above this line; values less than this indicate overinflation. Flattening of the diaphragm can also be assessed on a posteroanterior radiograph by drawing a line from the costophrenic to the costovertebral angle and measuring the height of the dome of each hemidiaphragm, which should be greater than 1.5 cm; this measurement is less sensitive than that performed on a lateral radiograph.

Another helpful sign in the detection of overinflation is an increase in the retrosternal clear space on the lateral chest radiograph. Direct measurement is preferred to subjective assessment; a distance greater than 2.5 cm between the posterior sternum and the most anterior margin of the ascending aorta is indicative of overinflation.

The most common cause of generalized overinflation of both lungs is emphysema. Less common causes include asthma, constrictive bronchiolitis, pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and lymphangioleiomyomatosis.

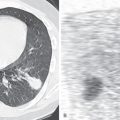

Radiographic manifestations of emphysema include irregular areas of radiolucency, local avascular areas, distortion of vessels, bullae, and hyperinflation (see Fig. 6.2 ). The parenchymal abnormalities can be subtle and difficult to detect on radiographs but are usually readily seen on CT, particularly high-resolution CT. On CT emphysema is characterized by the presence of areas of abnormally low attenuation. The areas of low attenuation generally have no visible walls; occasionally, however, walls 1 mm or less are seen, particularly in patients with paraseptal emphysema and bulla formation ( Fig. 6.3 ). On CT vessels can frequently be seen centered within the areas of low attenuation termed the centrilobular dot sign .

The most common radiographic abnormalities of asthma are bronchial wall thickening and hyperinflation. Hyperinflation in asthma is more common in children than in adults. High-resolution CT may demonstrate bronchial wall thickening, endobronchial mucous plugging, and areas of decreased attenuation and vascularity (mosaic attenuation); expiratory CT commonly shows multifocal air trapping ( Fig. 6.4 ).

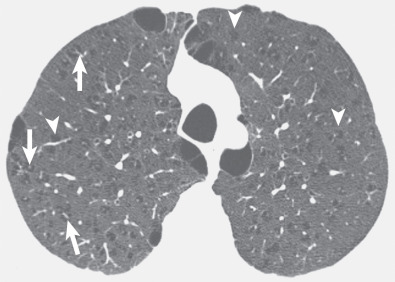

The radiographic manifestations of severe constrictive bronchiolitis (synonym: obliterative bronchiolitis and bronchiolitis obliterans) consist of hyperinflation and a decrease in peripheral vascular markings. In the majority of cases, however, constrictive bronchiolitis results in no definite abnormality on the chest radiograph. Inspiratory and expiratory high-resolution CT scans are the best imaging techniques for the assessment of patients with clinical and functional features suggestive of constrictive bronchiolitis. The CT findings consist of areas of decreased attenuation and vascularity on inspiratory CT scans and air trapping on expiratory scans ( Fig. 6.5 ). Redistribution of blood flow to uninvolved lung results in a heterogeneous pattern of attenuation and vascularity (mosaic attenuation). Common associated findings include bronchial dilation and bronchial wall thickening.

Local Excess of Air

Isolated overinflation of a lobe or segment or of one or more lobes occurs in two different sets of circumstances: with and without air trapping. Distinction between the two is of major diagnostic importance.

Overinflation with air trapping results from obstruction of the egress of air from affected lung parenchyma. It is seen most commonly in bronchial atresia or congenital lobar overinflation or distal to an endobronchial foreign body as a result of check-valve obstruction in children. Obstructive hyperinflation distal to an endobronchial foreign body or tumor is rarely seen in adults. In a review of the radiographic patterns of 600 cases of bronchogenic carcinoma, overinflation distal to a partly obstructing endobronchial lesion was not seen in any case. The volume of lung behind a partly obstructing endobronchial lesion in adults is almost invariably reduced at total lung capacity. Despite this smaller volume, the density of affected parenchyma is typically less than that of the opposite lung as a result of decreased perfusion (oligemia) secondary to hypoventilation-mediated hypoxic vasoconstriction. The overall effect is an increase in radiolucency despite the reduction in volume.

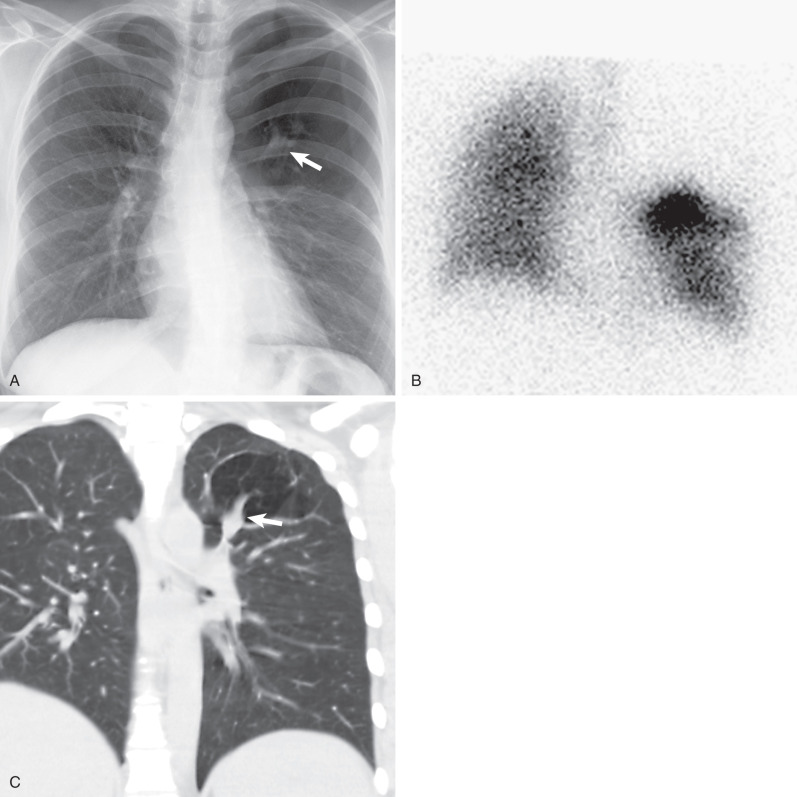

Congenital bronchial atresia is a rare anomaly that results from congenital focal obliteration of a proximal segmental or subsegmental bronchus with the normal development of distal structures. It usually involves a segmental bronchus, most commonly the apicoposterior segmental bronchus of the left upper lobe. The characteristic radiologic manifestations consist of an area of pulmonary hyperlucency and a perihilar opacity ( Fig. 6.6 ). The hyperlucency results from oligemia and an increase in the volume of air within the affected segment because of collateral air drift via interalveolar, bronchioloalveolar, and interbronchiolar connections (pores of Kohn, canals of Lambert, and channels of Martin, respectively) . The perihilar opacity may be round, oval, or branching and is due to the accumulation of secretions and mucoid impaction distal to the bronchial atresia. The abnormalities can be recognized on a chest radiograph but are more clearly defined by CT. CT demonstrates bronchial dilation immediately distal to the atresia; mucoid impaction within the ectatic bronchus (bronchocele); occlusion of the bronchus central to the bronchocele; and overinflation, decreased attenuation, and decreased vascularity distal to the bronchial atresia. Mucoid impaction typically has very high signal intensity on T2-weighted MR images. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy may be required to exclude acquired proximal bronchial obstruction by tumor, a foreign body, or an inflammatory stricture.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree