Demyelinating Disease

Multiple Sclerosis

MS is still a disease of unknown pathogenesis, although generally viewed as autoimmune in type. Incidence is higher in women, and in Caucasians of Northern European descent living in temperate zones. Most patients are 20 to 40 years of age at diagnosis, although presentation in older patients occurs. Although four major clinical subtypes are recognized, 85% of patients fall into the relapsing-remitting MS subtype in which relapses of disease alternates with periods of remission.

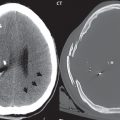

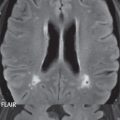

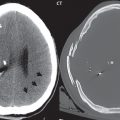

Dissemination of lesions in space and time is required for diagnosis. The revised McDonald criteria requires for disease diagnosis two focal, hyperintense lesions seen on T2-weighted scans, with one each in any of the following four areas: periventricular, juxtacortical, infratentorial, and spinal cord. A new lesion on follow-up scan or the presence on a single scan of asymptomatic enhancing and nonenhancing lesions fulfills the temporal requirement. MS plaques are poorly visualized on CT, with MR the definitive imaging modality.

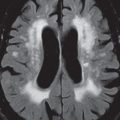

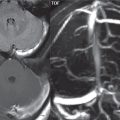

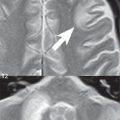

The hallmark of MS is punctate white matter lesions (plaques), in particular in the immediate periventricular region (and, specifically, perivenular in location). Chronic lesions tend to be small, with active lesions larger, with less well-defined margins. Acute lesions may evoke mild vasogenic edema. Disease involvement is typically asymmetric in nature, when comparing the right and left sides of the brain, one of many differentiating features from chronic small vessel white matter ischemic disease. There is a predisposition for the occurrence of lesions in characteristic areas ( Fig. 1.102 ). These include the immediate periventricular white matter, the corpus callosum (with even greater specificity for lesions that have a flat ependymal margin, or lesions that radiate along the white matter tracts from the ventricular surface), immediately adjacent to the temporal horns (an unusual area for lesions in chronic small vessel white matter ischemic disease), the colliculi, middle cerebellar peduncles, pons, and medulla ( Fig. 1.103 ). Optic nerve lesions also occur, and can be the reason for initial clinical presentation. Rarely, a solitary giant lesion can be seen, mimicking primary neoplasm, metastatic disease, or infection.

MS plaques in general are best visualized on FLAIR (as focal high signal intensity lesions), with high-resolution 3D scan acquisition at 3T preferred. Callosal lesions are often best detected in the sagittal plane. MS plaques also demonstrate low signal intensity on T1-weighted scans, another minor differentiating point from chronic small vessel white matter ischemic disease in which the lesions are typically poorly visualized on T1-weighted scans. Some chronic plaques demonstrate very low signal intensity, with these referred to in the literature as “black holes.” Diffusion weighted scans may depict active lesions as hyperintense (another distinctive imaging feature), which in the majority of cases is due to “T2 shine through” (the T2-weighting of the sequence), rather than representing true restricted diffusion. Gray matter lesions do occur, but are not well seen in general on conventional MR pulse sequences. Use of newer techniques such as MP2RAGE and double inversion recovery can improve detection of cortical gray matter lesions. Although not readily evident on clinical scans, there also is a more generalized involvement of white matter, with otherwise normal appearing white matter distinctive by MR parameters from that in the normal population by quantitative measures. Nonspecific findings in chronic disease include ventricular enlargement, cerebral atrophy, and thinning of the corpus callosum. The absence of lesions in the brain does not rule out the diagnosis of MS, with a complete evaluation including imaging of the cervical and thoracic cord, and the conus.

The majority of visualized lesions are chronic in nature and do not demonstrate contrast enhancement. Lesion enhancement is transient, exists for less than 4 weeks in most cases, correlates with active disease, and is a marker for new lesions ( Fig. 1.104 ). Both punctate and ring enhancement occur, and are common. An incomplete arc of enhancement adjacent to a lesion can also occur. Neurologists consider contrast administration to be a mandatory part of the exam, to assess active disease. In patients evaluated by MR during quiescent periods of the disease clinically, few if any enhancing lesions will be seen. When lesion enhancement is seen, it typically involves only a few lesions, although in rare instances, particularly with initial symptomatic presentation, there may be a large number of enhancing white matter plaques.

The severity of disease involvement varies widely. Early in the disease course, few plaques may be seen. In late stage involvement, the periventricular plaques may become confluent. There can be some overlap in imaging appearance, in any single patient exam, with SLE (in which multiple small subcortical and deep white matter lesions can be seen) and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. Lesions in SLE, however, are usually not immediate periventricular in location.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree