LEARNING OBJECTIVES

1. What is diagnostic mammography, and how is it defined?

• Studies directed by radiologists

• At least a few images are done with spot compression paddle

• Patient groups commonly undergoing diagnostic mammography

Symptomatic (women and men)

Callback from screening for evaluation of a potential abnormality

Post lumpectomy and radiation for the first 7 years

Patient with a probably benign lesion undergoing follow-up

• Standardization of imaging algorithms

2. What are the common indications for various additional views, and how is each done?

• Spot compression—how we define “spot” compression and why

Spot compression paddle

Frameless spot compression paddle

• Spot compression magnification

• Spot compression tangential

• Spot compression rolled

• 90-Degree lateral (lateromedial [LM] and mediolateral [ML])

• Cleavage

• Lateromedial oblique (LMO)

• Superolateral to inferomedial oblique (SIO)

• From below (FB)

3. For lesions initially seen in one view and in establishing mammographic–ultrasound concordance, how do you apply triangulation concepts?

• Use of rolled views

• Use of 90-degree lateral views

In conjunction with the mediolateral oblique (MLO) view

In conjunction with MLO and craniocaudal (CC) views

• Stepwise approach

APPROACH TO DIAGNOSTIC BREAST IMAGING

In our practice, the diagnostic patient population is composed primarily of three groups of patients. Those who require additional evaluation of potential abnormalities detected on their screening mammograms, patients presenting with signs and symptoms possibly reflecting the presence of breast cancer, and women who have a history of lumpectomy and radiation therapy (we consider this last group of women as diagnostics for the first 7 years following their treatment, after which they are returned to the screening population—see Chapter 11). Additional but relatively small groups of diagnostic patients are women with probably benign lesions undergoing short interval follow-up and men with breast-related symptoms (1). Many different approaches to diagnostic mammography are available. In general, diagnostic studies usually include at least one or more images done using the spot compression paddle.

Our approach has been to develop a consultative breast service such that we run the Center more like a clinical practice than like a radiology service. We believe that as breast imagers we are in a unique position to provide a desperately needed comprehensive breast health service. In many communities, breast care is disjointed with no standardization and provided haphazardly by general surgeons, gynecologists, family practitioners, and internists. Having someone who can put things together for patients is quite helpful. As radiologists, we have at our disposal all of the imaging modalities that are critical in the diagnosis and subsequent management of patients. If we complement this with clinical acumen, we can provide a much-needed service. Functioning as a team member, we can serve a pivotal role in patient care. We have elected to develop our service with these concepts in mind: the radiologist as a clinical breast imager. Our approach to patients with possible breast cancer is to evaluate them as needed to reassure them of benign findings, low likelihood of malignancy, or undertake the necessary procedures to establish a definitive diagnosis.

As discussed in Chapter 2, women with potentially abnormal mammograms are scheduled for diagnostic studies in 15-, 30-, and 60-minute time slots, depending on the abnormality detected at screening. Our approach to these patients is to do whatever it takes, on their return trip, to arrive at a definitive, justifiable recommendation. In some patients, this may take one or two additional mammographic images, while in others, additional mammographic images, correlative physical examination, ultrasound, and an interventional procedure (cyst aspiration, ductogram, FNA, and biopsy) may be indicated. For those patients in whom a biopsy is indicated, we offer the patient the option of having it done immediately. Unless requested by the patient, we do not reschedule them for ultrasounds, aspirations, ductograms, or biopsies. Approximately 99% of patients opt for having the biopsy the same day. Most patients are appreciative of being offered this option. Additionally, we have a commitment from our Pathology Department for a 24-hour turnaround time on core biopsies. Consequently, we see our biopsy patients the day following their procedure, at which time findings are discussed directly with the patient and referrals are made as needed on the basis of the results: (i) Screening mammogram in one year for patients with benign congruent results; (ii) Surgical consultation for patients with high-risk lesions (e.g., atypical ductal hyperplasia); and (iii) MRI and surgical consultation for patients with a malignant lesion.

Although there are many projections available to us during diagnostic mammography, I have purposely limited the discussion to those used most often. Having a handle on the material discussed in this chapter will enable you to evaluate the vast majority of patients presenting to your diagnostic center in a logical and efficient manner. I encourage the standardization of diagnostic imaging evaluations. Appropriate and justifiable recommendations become self-evident, and confidence in your work is increased greatly.

SYMPTOMATIC PATIENTS: IMAGING ALGORITHMS

Our basic imaging algorithms for symptomatic patients are listed in Table 3.1. In symptomatic women who are 30 years or older presenting with a “lump,” focal tenderness, skin dimpling, nipple retraction, or other focal symptoms, a metallic BB is placed at the site of concern and CC and mediolateral oblique (MLO) views are obtained bilaterally. In addition to the standard images, the technologist obtains a spot tangential view of the site of concern as pinpointed by the patient. Correlative physical examination and an ultrasound are done unless completely fatty tissue is imaged at the site of concern on the routine and spot tangential views, and there is no possibility that the area of concern is excluded from the image. If the metallic BB is at the edge of the film (Fig. 3.1), not seen on CC and MLO images, or marks an area from which tissue may be excluded (e.g., axilla, upper inner quadrant posteriorly, areas of inframammary fold [IMF]) (Fig. 3.2), correlative physical examination and ultrasound are indicated. In women with nipple discharge, a ductogram may be done if it is determined that the discharge is spontaneous and arising from one duct on physical examination (see Chapter 12). We do not consider diffuse, cyclical tenderness as an indication for a diagnostic study; these women are scheduled for screening mammography.

In symptomatic women under the age of 30, or those who are pregnant or lactating (regardless of age), physical examination and ultrasound (see Figs. 4.45 and 4.47) are our starting point (2,3). If cancer is suspected on the basis of this initial evaluation, a full mammogram is obtained to more completely evaluate the lesion, as well as the rest of the tissue in that breast, the contralateral breast, and the axillae.

Table 3.1 IMAGING ALGORITHMS FOR SYMPTOMATIC PATIENTS

Symptomatic Patient (30 y of age or older) (“Lump,” focal tenderness, dimpling, nipple retraction) Metallic BB placed at the site of concern Bilateral CC and MLO views Spot tangential view at the site of concern Physical examination and ultrasound (unless area of concern is totally fatty and there is no chance, the finding is excluded from the field of view) Symptomatic Patient (under age 30; pregnant or lactating regardless of age) (“lump,” focal tenderness, dimpling, nipple retraction) Physical examination Ultrasound Mammogram (bilateral) if cancer is suspected on physical examination and ultrasound |

SPOT COMPRESSION VIEWS

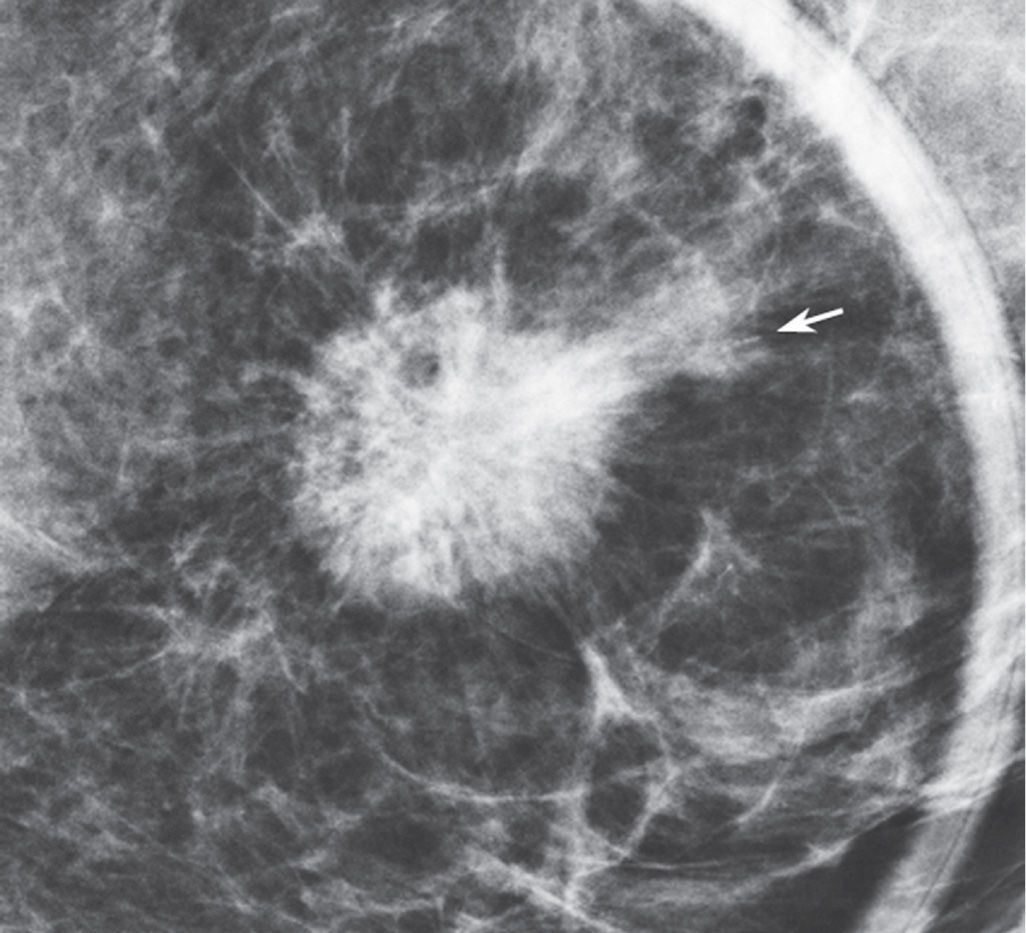

Spot compression views are the most common additional views obtained in our practice. The area of concern is immobilized and maximally compressed in two projections unless it is seen only in one view initially. Spot compression views minimize superimposition and geometric unsharpness, and resolution is improved as the object to film distance is decreased. When evaluating spot compression views, it is important to ensure that the area of concern is included in the field of view (Fig. 3.3). As focal compression is applied, lesions can “roll,” or “squeeze,” out of the field of view. For purposes of orienting ourselves on the spot compression views, we like to include surrounding tissue on the image. Consequently, we do not cone down on spot compression views, and, although not compressed, surrounding tissue is evaluated and used to assure inclusion of the area of concern. While at the point of reviewing a spot, you are clearly evaluating a specific potential finding, keep an open mind (eye), and be sure to evaluate all of the tissue on the image and that surrounding the paddle. The original focus of attention may turn out to be benign, and an unsuspected malignant process may become apparent (Fig. 3.3).

FIG. 3.1 • Lesion exclusion, invasive ductal carcinoma not otherwise specified. CC (A) and MLO (B) views done in a 53-year-old patient presenting with a “lump” in the right breast. A radiopaque triangular marker is used to denote the location of the palpable finding, and metallic BBs mark the nipples. Loosely clustered round calcifications are noted in the upper outer quadrant of the left posteriorly; these are stable. The radiopaque marker (arrow) is at the edge of the film on the CC view and is barely seen on the MLO view such that the lesion may have been excluded from the field of view. When the metallic marker used to denote a site of clinical concern is at the edge of the images, or not included on the images at all, correlative physical examination and ultrasound are indicated even if fatty tissue is imaged. C: Ultrasound. On physical examination, a hard mass is readily apparent just above the IMF on the right. An oval iso-to-slightly hyperechoic mass (arrows) with posterior acoustic enhancement is imaged interposed between the skin and one of the lower ribs. BI-RADS 4B: Suspicious abnormality, biopsy is indicated.

To obtain the maximum benefit of spot compression views, we use a small round paddle (Fig. 3.4A) or a frameless spot paddle (Fig. 3.4B). The frameless spot paddle centers a 7.5-cm spot compression cup into an 18 × 24 cm paddle and eliminates the metal frame around the spot device; this permits visualization of the surrounding tissue with some compression and eliminates the artifact (distraction) generated by the metal frame of the paddle. All of the diagnostic images done at our facilities are done with the paddles shown in Figure 3.4A, B; we have removed the larger rectangular and square paddles from our mammography rooms (Fig. 3.4B, C). Although in women with larger breasts using the round spot presents a challenge in getting the area in the field of view, it is a challenge we welcome and overcome routinely. Using larger “spot” paddles to make it easier for the technologist to include the area in the field of view in many ways defeats the purpose of focal compression. If your “spot” compression views include more than half of the breast (Fig. 3.4E), what are you really accomplishing?

Indications for spot compression views are listed in Table 3.2. As a general rule, if we are not sure a lesion is present, our starting point is spot compression. Spot compression views are used to evaluate densities seen in only one view (Fig. 3.5), masses with possibly obscured margins (Figs. 3.6 through 3.11), asymmetric tissue (Fig. 3.12), and possible areas of distortion (Fig. 3.13). Additionally, spot compression can be used to reach and image lesions that are excluded from routine screening views (Fig. 3.14): lesions close to the chest wall, in the axillary tail, or high in the upper inner quadrants (4–6). If there is blurring related to inadequate compression (e.g., subareolar or IMF areas), or focal areas of underexposed tissue, spot compression can help overcome these technical limitations.

FIG. 3.2 • Lesion exclusion, metastatic melanoma. A: MLO view of the left breast in a 41-year-old woman presenting with a painful “lump” underneath her left arm. The metallic BB (white arrow) used to mark the site of the “lump” is apparent on the MLO, but it is not seen on the CC view (not shown). Fatty tissue is imaged in the area of concern to the patient on the MLO and the spot tangential view (not shown). Surgical clips (black arrow) are imaged in the left axilla related to a sentinel lymph node biopsy done at the time of surgery for a melanoma on her back 2 years ago. Even though these images are normal, a described clinical finding in the axilla requires additional evaluation because as compression is applied, masses can roll out from under the paddle and may not be included on the images. Correlative physical examination and an ultrasound are indicated. B: Ultrasound. A hard mobile mass is palpated in the left axilla; tenderness is elicited on palpation. A lobulated, markedly hypoechoic mass with circumscribed margins is correlated with the palpable finding. Biopsy is indicated. BI-RADS 4C: Suspicious abnormality, biopsy is indicated. C: Cores. Portions of the cores are dark brown, highly suggestive of metastatic melanoma. This diagnosis is confirmed histologically.

It is important to emphasize that for most patients spot compression views are done in two projections. It is only when a potential lesion is seen in only one view (Fig. 3.5) that we limit the spots to the projection in which the potential abnormality is seen. If no abnormality is confirmed on the spot compression view, we do no additional images. If the spot compression view confirms a mass or distortion, we need to determine its location in the orthogonal plane by using rolled views or a 90-degree lateral view (see triangulation). We make no assumptions about the possible location of the lesion in the orthogonal plane. If on the screening images a potential lesion is seen in both projections, spot compression views are done in both before any effort is made to take the patient to ultrasound. Once the lesion is identified and fully evaluated with CC and MLO spot compression views, mammographic–ultrasound concordance can be established easily (see discussion in Chapter 4). Although for many of the figures used in this chapter one mammographic and ultrasound projection is provided, orthogonal images are done routinely in the evaluation of patients (e.g., spot compression views are obtained in two projections, and orthogonal images of the lesion are taken on ultrasound); space constraints limit the number of images I can present. Also as described in subsequent sections, we do not do 90-degree lateral views routinely in our diagnostic evaluations. We relegate the use of these projections to specific situations and to answer specific questions.

FIG. 3.3 • Spot compression paddle, lesion inclusion. Spot compression views of the right breast in CC (A) and MLO (B) projections. The patient is called back for evaluation of a round mass noted as a new finding on the screening mammogram. What do you think? The mass prompting the callback (long arrow) is noted in both spot compression views; however, in evaluating the images please step back and review everything directly under the paddle as well as the tissue that is outside of the compression field. In this patient, a low-density irregular mass (short arrow) with spiculated margins is imaged in the MLO projection only. Where is this on the CC spot? Reviewing the screening images is not helpful (e.g., no mass with spiculated margins is apparent on the standard images). Would you do anything else? Given the finding on the MLO view, you cannot stop. In this patient, the technologist is asked to do a second spot in the CC projection moving slightly medial to the current position. C: Second spot compression view in the CC projection. On this additional projection, you confirm the presence of an irregular mass (short arrow) with spiculated margins in the CC projection and again image the round mass with circumscribed margins prompting the callback (long arrow). The round mass is a cyst; the mass with spiculated margins is an invasive ductal carcinoma.

FIG. 3.4 • Spot compression paddles. A: This is one of the paddles that we use for our spot compression images (spot compression, spot compression magnification, spot tangential, and spot rolled views). This paddle is particularly helpful in evaluating potential lesions that are posterior or axillary in location. B: Frameless spot paddle. A 7.5-cm compression cup is centered on an 18 × 24 cm paddle. This, in combination with the paddle shown in part A, is the paddle we use for all of our spot compression views. The absence of a metal frame permits evaluation of all of the tissue surrounding the spot and eliminates the metallic arm artifact that is seen on images when the paddle in part A is used. The diagnostic images shown throughout this chapter and the book were done with the spot paddle shown in part A or this frameless paddle. Rectangular (C) and square (D) compression paddles. We do not use these two types of paddles (we do not even have them in our facility). Their geometry and size are such that they preclude obtaining maximal compression to a small area of the breast. In many patients, paddles of this size include more than half or the entire breast, negating the benefit of “focal” compression. E: Spot compression image done with rectangular paddle. Irregular mass with indistinct margins (arrow) is present. Note the amount of breast tissue and pectoral muscle included in the image. When this amount of pectoral muscle is included on the image, compression of the tissue anteriorly (where the mass is located) is likely to be limited, negating the benefits of doing “spot” compression views. We define spot as that obtained with the compression paddles shown in part A or B; we do not use the paddles shown in parts C and D in our diagnostic evaluations.

Table 3.2 INDICATIONS FOR SPOT COMPRESSION VIEWS

Evaluation of questionable areas Density Asymmetry Distortion Evaluation of masses Characterization of margins Effect on surrounding tissue Inclusion of tissue Posterior Axillary Upper inner quadrant Technical issues Blurring Underexposure (focal) Localizations (preoperative) See Chapter 12 |

Factors to consider when doing magnification views are listed in Table 3.3. Magnification views are obtained by moving the breast away from the digital detector (i.e., increasing the object to image distance and decreasing the source to object distance), thereby creating an air gap. A grid is not needed because scatter radiation is eliminated in the air gap. As the object to image distance increases, the amount of magnification increases (e.g., 1.5×, 1.8×); however, this is associated with a loss of resolution from an increasing penumbra effect. The use of a small focal spot (0.1 mm) helps overcome the loss of resolution. With the small focal spot, however, exposure time is increased, leading potentially to motion. In an effort to obtain acceptable exposure times, the kilovolt used to obtain magnification views can be increased by at least 2 compared with that used for screening views.

FIG. 3.5 • Pseudolesion, superimposed glandular tissue. A: CC view, right breast photographically coned. A round density (arrow) possibly representing a mass is noted on the screening study. Time and time again, you will find that what you perceive on screening studies may be misleading. “Lesions” of concern on the screening study turn out to be “imaginomas,” and true lesions look innocuous. Screening is for detection, not characterization. We make no attempt to describe features or arrive at any conclusion of possible lesions detected on a screening mammogram. Even in women who have an obvious cancer, additional views are helpful in characterizing the imaging features of the lesion, extent of the lesion, detecting additional unsuspected lesions, allowing us to establish rapport with the patient and expedite her care by undertaking imaging-guided biopsy when she returns for additional views. B: Spot compression view. No abnormality is identified. Surrounding benign calcifications confirm that the right area of tissue has been evaluated on the compression view. The original density represents superimposition of normal glandular tissue (presumably tissue that is inadequately compressed). Since the “potential mass” is not confirmed on the view in which it is seen, no additional views need to be done in the CC or oblique projections. (From Cardeñosa G. Breast Imaging [The Core Curriculum Series]. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.)

FIG. 3.6 • Invasive ductal carcinoma with lobular features. CC (A) and MLO (B) spot compression views (done using the frameless paddle). An irregular isodense mass with spiculated margins and two associated round calcifications is confirmed in the left breast (see Fig. 2.43 for the screening views on this patient). C: Ultrasound. On the basis of the location of the lesion on the mammographic images, we walk into the ultrasound with a specific anticipated location for the mass. An irregular, vertically oriented mass with spiculated and angular margins, an echogenic rim, and shadowing is identified at the 11:30 o’clock position, 8 cm from the left nipple as expected on the basis of the mammogram. As with the spots, orthogonal images of the mass are done as part of our ultrasound evaluation, only the radial (RAD) projection is shown here. At the time of the ultrasound, ultrasound-guided palpation is done to determine whether the finding is palpable; the mass is not palpable in this patient. BI-RADS 4C: Suspicious abnormality, biopsy is indicated. Ultrasound-guided biopsy is done to establish the diagnosis.

FIG. 3.7 • Invasive ductal carcinoma, intermediate to high grade. Spot compression view (done using the frameless paddle), CC projection. A dense round mass with indistinct and spiculated margins as well as associated calcifications (arrow) is present in the lower inner aspect of the left breast. See Figures 2.46, 4.39D, and 5.21 for screening, ultrasound, and MRI images on this patient, respectively. Spot compression view in the oblique projection is not shown. BI-RADS 4C: Suspicious abnormality, biopsy is indicated. Ultrasound-guided core biopsy is done.

Magnification views can be done using the regular compression paddle or a spot compression paddle (4,7). With the regular compression paddle, a maximal amount of tissue is included on the image; however, compression may not be optimized. As described for spot compression views, we use the round spot compression or frameless spot paddle (Fig. 3.4A, B) for all of our magnification views (except those done for a ductogram, which we do with the full paddle). This maximizes the compression at the site of concern, reduces exposure times, and helps minimize the likelihood of motion. The disadvantages of using the spot compression paddle for magnification are related to the smaller field of view and include the need for accurate positioning so that the area being evaluated is included in the spot view, difficulty in orienting the imaged area relative to the non-magnified view (has the area of concern been included on the image?), and the need to do several images when dealing with a large area of calcifications.

Indications for spot compression magnification views are listed in Table 3.4. Although many use magnification views to evaluate masses and possible areas of distortion regardless of the presence of calcifications, we use spot compression magnification views almost exclusively to evaluate and characterize calcifications (Figs. 3.10B, 3.15, and 3.16) and masses (Fig. 3.17) or areas of distortion having associated calcifications.

FIG. 3.8 • Invasive ductal carcinoma, low to intermediate grade. A: Spot compression view, mediolateral oblique projection. A dense round mass with indistinct margins is confirmed on the spot compression views (only MLO projection is shown). See Figure 2.47 for the screening views on this patient. At what location (be specific) would you expect to find this lesion on ultrasound? B: Ultrasound. Even though this lesion projects below the level of the nipple on the MLO view, it is actually above the level of the nipple and is identified at the 2:30 o’clock position, 8 cm from the nipple (see triangulation discussion). The mass is vertically oriented with angular margins and an echogenic rim and correlates with the mammographic findings. Only the radial (RAD) projection is shown. In a patient with a personal history of breast cancer and the development of a new dense mass with these mammographic and ultrasound features, a malignancy is expected. BI-RADS 4C: Suspicious abnormality, biopsy is indicated. Ultrasound-guided core biopsy is done.

FIG. 3.9 • Invasive ductal carcinoma, low nuclear grade. Spot compression view, MLO projection. An irregular isodense mass with spiculated margins is confirmed on the spot compression views (only MLO projection shown). See Figure 2.49 for the screening views on this patient. At what specific location do you expect to find this lesion on ultrasound? See Figure 4.39C for the ultrasound on this patient. BI-RADS 4C: Suspicious abnormality, biopsy is indicated and done. The spot compression paddle was used for this image; a portion of the metal frame is seen surrounding the paddle.

FIG. 3.10 • Multicentric disease: invasive carcinoma with lobular features and ductal carcinoma in situ. A: Spot compression view in the MLO projection. An irregular high-density mass with spiculated margins is confirmed on the spot compression views (CC projection not shown). The spot compression paddle was used for this image; a portion of the metal frame is seen surrounding the paddle. See Fig. 2.50 for screening views on this patient. BI-RADS 4C: Suspicious abnormality biopsy is indicated. At what location (be specific) would you expect to find this lesion on ultrasound? See Figure 4.39E for the ultrasound on this patient. Ultrasound-guided core biopsy is done to establish the diagnosis of invasive carcinoma with lobular features. You will recall that in addition to the mass, a cluster of calcifications was also detected in the lateral aspect of the breast of this patient. B: Spot compression magnification view in the CC projection confirms a cluster of pleomorphic calcifications that includes linear forms, and some of the calcifications demonstrate a linear orientation. BI-RADS 4C: Suspicious abnormality biopsy is indicated. Stereotactically guided core biopsy is done to establish the diagnosis of DCIS.

FIG. 3.11 • Invasive ductal carcinoma, intermediate nuclear grade. Spot compression view (done using the frameless paddle) in the MLO projection. An oval isodense mass with partially obscured and indistinct margins is confirmed on the spot compression views (CC projection not shown). BI-RADS 4C: Suspicious abnormality biopsy is indicated. Ultrasound-guided core biopsy is done. See Figures 2.40 and 4.39B for the screening and an ultrasound image on this patient, respectively.

FIG. 3.12 • Focal parenchymal asymmetry, fibrocystic complex. CC (A) and MLO (B) views in a 40-year-old woman with no prior studies. Parenchymal asymmetry is noted in the upper outer quadrant of the right breast, zone B. BI-RADS 0: Need additional imaging evaluation. CC (C) and MLO (D) spot compression views (done with the frameless paddle) demonstrate glandular tissue with intermingled fat, areas of scalloping, and no bulging contours. Since this is the patient’s first mammogram, correlative physical examination and ultrasound are done. On physical examination, globular, mobile tissue is palpated corresponding to the parenchymal asymmetry seen mammographically. E: On ultrasound (orthogonal images not shown), dense fibrous tissue with multiple cysts of varying sizes is imaged corresponding to the asymmetric tissue. BI-RADS 2: Benign finding.

FIG. 3.13 • Invasive lobular carcinoma. CC (A) and MLO (B) spot compression views of the left breast. Distortion without a definable mass is the predominant finding on the CC spot compression view. This is more mass-like on the oblique spot. See Figure 2.44 for the screening views on this patient. C: Ultrasound. On physical examination, a hard mass is readily palpable (PALP). A mass with intense shadowing and spiculated margins is imaged in the upper inner quadrant of the left breast; only radial (RAD) plane is shown. BI-RADS 4C: Suspicious abnormality, biopsy is indicated. Ultrasound-guided core biopsy is done. See Figure 5.22A for an MRI image on this patient.

ROLLED OR CHANGE OF ANGLE VIEWS

Rolled or change of angle views are commonly used in conjunction with spot compression views in establishing the presence of a lesion (8). For rolled views, we also use the round spot compression paddle. Breast tissue is often planar and changes in appearance as tissue is rolled or the angle of the incident beam is changed (Fig. 3.18). In contrast, most breast cancers (except some invasive lobular carcinoma and, small, <5-mm, invasive ductal carcinomas) are three dimensional. As tissue is rolled, the contour and appearance of most cancers do not change significantly. Rolled or change of angle views can also be used to triangulate the location of a lesion (Fig. 3.19), or to move a lesion away from glandular tissue so that it is surrounded by fat and evaluated more completely.

FIG. 3.14 • Use of spot compression to include more tissue in the field of view. MLO (A) and CC (B) views of the right breast in a 40-year-old patient who presents with a “lump” in the right breast. A mass is partially seen on the MLO view superimposed on the pectoral muscle (arrow). Metallic BB is noted above the partially imaged mass close to the edge of the image. Neither the lesion nor the metallic BB is included on the CC view; however, tissue is seen extending to the edge of the film (arrows). C: Spot compression view in an exaggerated craniocaudal lateral (XCCL) projection. Isodense oval mass with circumscribed margins is now seen in its entirety surrounded by subcutaneous fat. Spot compression views can be helpful in evaluating areas that may be excluded from the field of view (e.g., axillary tail, axilla, upper inner quadrants posteriorly, etc.). D: Ultrasound demonstrates a hypoechoic mass with small anechoic round areas and posterior acoustic enhancement (arrow). BI-RADS 4A: Suspicious abnormality, biopsy is indicated. Ultrasound-guided core biopsy is done. The lesion decreased significantly in size following the first core sample and completely resolved following the second core sample, consistent with the findings described histologically of fibrocystic change with apocrine and epithelial lined cysts. (From Cardeñosa G. Breast Imaging [The Core Curriculum Series]. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.)

For triangulation purposes, rolled or change of angle views can give the approximate location of a lesion seen in only one view on the screening study. You can expect lesions to move with their surrounding tissue. If there is a lesion on the CC view that cannot be identified with certainty on the MLO view, rolled views can be done. If the top of the breast is rolled medially while the lower part is rolled laterally and the lesion moves medially, this suggests the lesion is in the superior portion of the breast. If the lesion does not shift in position significantly, the lesion is in the central portion of the breast, and if the lesion moves laterally (Figs. 3.19 and 3.20), it is in the inferior aspect of the breast. This can be confirmed by repeating the image and rolling the upper portion of the breast laterally and the lower portion medially. Given an approximate location for the lesion, the MLO, or a 90-degree lateral view, can now be reviewed, and additional workup of the upper, central, or lower portions of the breast is undertaken.

Table 3.3 MAGNIFICATION VIEWS

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree