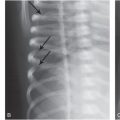

Figure 10.1 Toddler’s fracture. AP view of the right tibia in a nine-month-old infant who fell from the bed shows a nondisplaced oblique fracture (arrows) of the distal tibial metaphysis. The fracture does not enter the physis, and no displacement or angulation is present.

This subtle injury may be invisible or overlooked initially on standard frontal and lateral radiographs, but oblique and/or high-detail images can reveal the characteristic oblique fracture in the mid-distal tibial diaphysis, and less commonly the metaphysis. Follow-up radiographs are usually confirmatory. Although skeletal scintigraphy or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may have a role in problematic cases of suspected toddler’s fractures, most cases with normal radiographs are managed presumptively based on clinical findings.

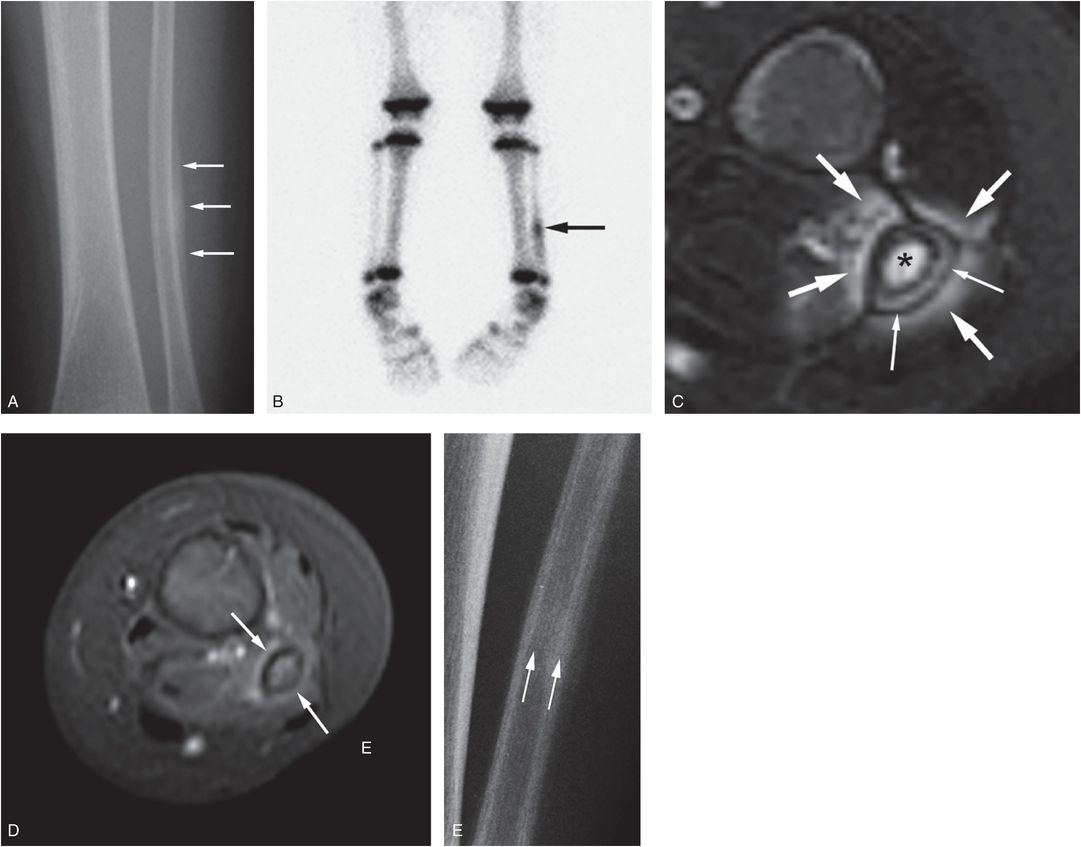

A less common site for a toddler’s fracture is the fibulas which usually involves the mid-distal portion of the bone. The absence of a clear history of trauma is not unusual for this accidental injury. Subperiosteal new bone formation (SPNBF) may be the only finding on initial imaging, and in the absence of trauma, an extensive work-up may be undertaken to explore the possibility of an infectious or neoplastic process (Fig. 10.2).

Figure 10.2 Fibular toddler’s fracture. A 13-month-old child with a left leg limp for one week. Initial radiograph of the entire extremity was reportedly normal. Fever was present for three days and there was a mildly elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate. A, AP radiograph of the left lower leg shows a focus of SPNBF (arrows). B, Anterior view of the 99mTc MDP bone scan shows corresponding increased uptake in the left distal fibula (arrow). Because of concerns of osteomyelitis, an MRI was performed. C, Axial T2-weighted FS image shows fluid signal within the medullary cavity (*) and surrounding the tibial diaphysis (thick arrows). Note SPNBF laterally (thin arrows). D, Following gadolinium there is only modest corresponding enhancement (arrows). E, High-detailed cone-down radiograph shows a faint fracture line consistent with a tibial toddler’s fracture (arrows).

When a fracture underlies the SPNBF, the most sensitive technique is often radiography, and oblique and high-detail images may be sufficient for diagnosis. Bilateral tibial and fibular stress fractures have rarely been reported (61, 62). Another site for a toddler’s fractures is the cuboid and these can present a diagnostic challenge (63, 64).

The “hyperextension toddler’s fracture” described by Swischuk et al. is characterized by buckling or impaction of the anterior tibial cortex (65). This is likely a higher energy event than the classic tibial toddler’s fracture, as illustrated by the mechanisms reported by these authors. Although usually accidental, the fracture patterns noted above can be seen with abusive assaults (see Fig. 3.61).

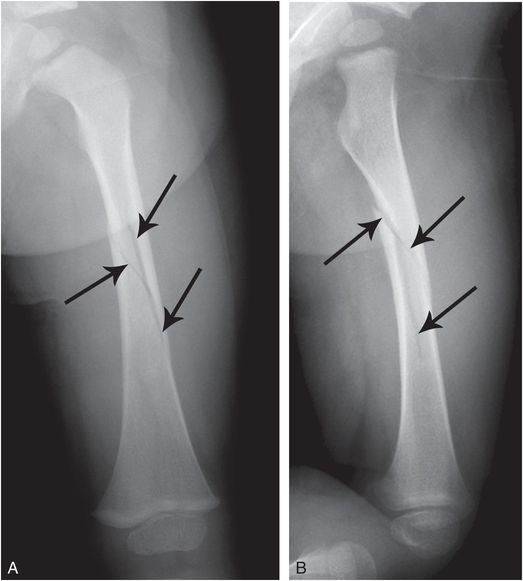

Much has been made of the significance of the spiral or oblique fracture pattern as an indicator of inflicted injury. These patterns simply imply a torsional force in the pathogenesis of the fracture, and are common with accidents (66). This injury pattern has been discussed in detail in Chapter 2. The patterns, particularly those involving the femur, can be occasionally seen in children who slip and fall while running (Fig. 10.3) (67–70).

Figure 10.3 Spiral femoral fracture with running. A 17-month-old boy who slipped while running. Parent immediately sought medical attention. AP (A) and lateral (B) views of the left femur demonstrate a spiral fracture (arrows). There were no clinical concerns and no further imaging was performed.

As emphasized elsewhere (see Chapter 3), femoral shaft fractures are commonly associated with abuse in nonambulatory children, but most are due to accidents in the ambulatory child (70–72). A history of a fall while an infant is being carried should be carefully considered as a plausible explanation for a femur fracture (Fig. 10.4).

Figure 10.4 Distal femoral impaction fracture due to fall with mother. While carrying her eight-month-old infant, the mother reportedly fell, landing on her right side. Medical attention was immediately sought. AP (A) and lateral (B) views of the left distal femur demonstrate a posteriorly impacted transverse fracture of the distal femoral metaphysis (arrows). There were no social concerns and further imaging was deemed unnecessary.

Haney and others published a multicenter series of 18 children, mainly infants, with transverse impacted distal femoral fractures. Thirteen fractures were deemed accidental and five were likely inflicted. They postulated a mechanism entailing an axial load delivered to the knee with a fall as an explanation for the imaging findings (73). The pattern is in keeping with the fracture shown in Fig. 10.4.

A variety of stationary activity devices are currently marketed that apply a mechanical load to the lower extremities. At least one of these has been described as a possible causative factor in femoral fractures in nonambulatory infants (74, 75), and other possible instances of injuries have been noted (76). Interestingly, limb fractures are quite uncommon as a consequence of high-chair accidents (77).

Fractures occasionally occur when a large child, adult, or other object falls on a child. The hazard of falling televisions has been well documented, and these events can have lethal consequences (see Fig. 19.29). Although head injuries are the principal concern, injuries involving the trunk and extremities have been described (Fig. 10.5) (78).

Figure 10.5 Falling television injury. A 16-month-old girl who reportedly pulled a 27-inch television set off a stand and onto herself. In the local hospital, drowsiness, ankle swelling, and periobital bruising was noted. Head and abdominal CT were negative. A, AP view of the left distal lower leg shows a slightly impacted fracture (arrow) of the distal tibia. Further imaging was not performed.

Upper extremity

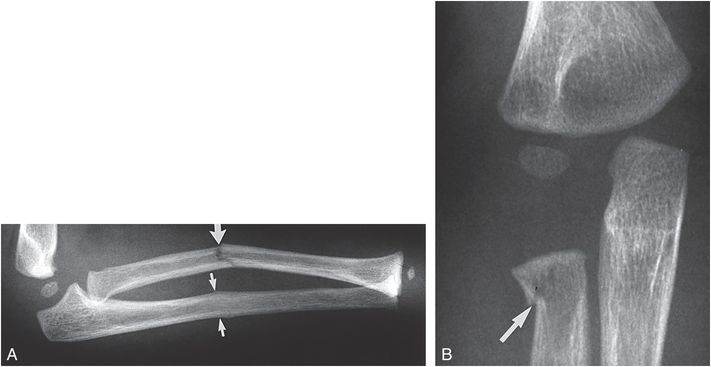

As with most nonspecific skeletal injuries of the lower extremity, the single most important factor is correlation of the imaging findings with a detailed description of the purported accidental event. Figure 10.6 illustrates the radiograph of a 12-month-old infant with a history of a “fall.” The radiographs demonstrate three fractures involving the upper extremity, and such injuries in an infant after a fall from a standing position would be unusual. The possibility of abuse was an initial concern, until a detailed and well-documented description of the events was provided. The child fell 4 ft from a sliding door onto her arm.

Figure 10.6 Fractures due to an accidental fall. A, Lateral view of the forearm in a 12-month-old infant with a history of a “fall” demonstrates an angulated midshaft radial fracture (large arrow) and a buckle fracture of the adjacent ulna (small arrows). B, An oblique view of the elbow shows a slightly impacted fracture of the radial neck (arrow). Abuse was initially suspected, but further history revealed that the child crawled out of an opened sliding glass door, falling 4 ft to the ground.

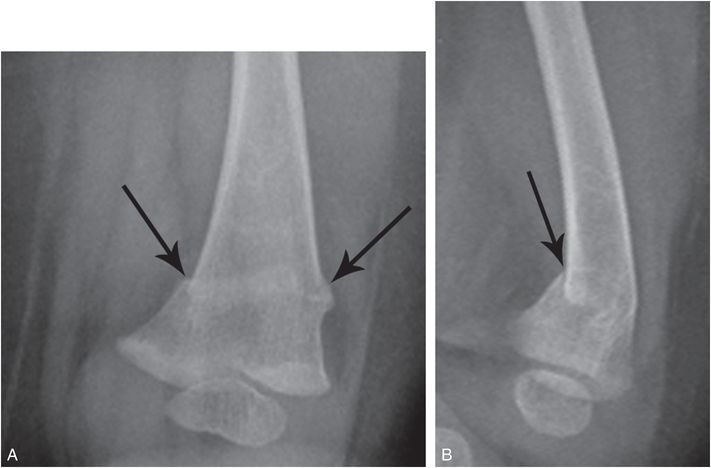

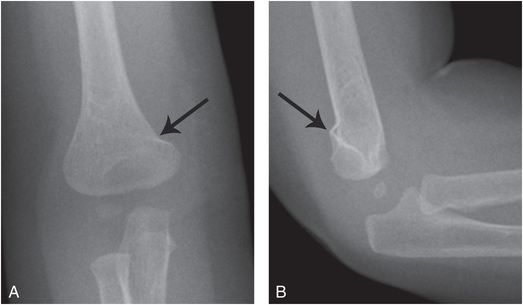

Humeral fractures are covered in depth in Chapter 4, but deserve special mention here. Supracondylar fractures are usually accidental injuries beyond infancy and can occur when children fall while running or playing (68, 69, 79). They do occur with abuse, particularly in infancy. This author has noted an accidental lateral condylar fracture of the distal humerus that showed a striking resemblance to the bucket handle pattern considered a high-specificity fracture for abuse (Fig. 10.7). For this reason, caution is urged in assigning the description of a bucket handle pattern to injuries of the distal humerus, as this is not a specific feature of inflicted injury at the elbow.

Figure 10.7 Lateral condylar humeral fracture. AP view of the elbow in a 14-month-old infant who was run over by a car demonstrates a fracture of the lateral aspect of the distal humeral metaphysis (arrows). This lateral condylar fracture has the appearance of a bucket handle lesion, a pattern not specific for abuse at this site.

Another vagary of humeral fractures has been pointed out by Hymel and Jenny (80). The authors described an accidental humeral fracture captured on videotape. The five-month-old infant was lying prone on a blanket. The two-year-old sister attempted to turn the child over by placing her hand under the axilla, rolling the child over to its back. The opposite arm was extended, and as the child began to roll, an audible snap was evident (Fig. 10.8). Radiographs demonstrated a spiral-oblique diaphyseal humeral fracture. The oblique humeral fracture shown in Fig. 10.9 reportedly occurred as the father attempted to turn the five-month-old over in the crib. It was difficult to fully exclude abuse in this case which had a history of neglect, but the purported mechanism was similar to that noted in Hymel and Jenny’s report (80). A similar mechanism was provided to explain the supracondylar fracture shown in Fig. 10.10. Recently, Somers and others noted humeral fractures in infants with histories suggesting a similar rare mechanism (81). The authors, as well as Dr. Carole Jenny’s accompanying editorial, urged caution in the interpretation of their data due to the lack of independent witnesses or video recordings (82).

Figure 10.8 Proposed mechanism for accidental humeral fracture in an infant. An attempt to roll the infant from a prone to a supine position by placing the hand under the right axilla results in a fracture of the left humeral shaft. This event was captured on videotape. (Redrawn from Hymel KP, Jenny C. Abusive spiral fractures of the humerus: a videotaped exception. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1996;150:226–8.)

Figure 10.9 Humeral shaft fracture, possibly accidental. AP view of the left humerus in a five-month-old demonstrates an oblique fracture of the diaphysis (arrows). The father said he attempted to roll the child over in the crib and heard a “pop,” followed by inability of the infant to move the left arm. There was evidence of previous neglect, but a SS and a Department of Social Service investigation considered that abuse was unlikely.

Figure 10.10 Supracondylar fracture, possibly caused by sibling. Seven-month-old was lying on the floor accompanied by the three-year-old sibling. The parent found the infant lying on his back with the right arm extended beneath him. The parent surmised, but did not witness, that the sibling had attempted to roll the infant from a prone to supine position. The infant was consolable, but medical attention was immediately sought because of arm swelling – radiographs were not obtained. Because of decreased range of arm motion, the family returned for care three days later. A, B, AP and lateral views of the right elbow reveal a minimally angulated supracondylar humeral fracture (arrows). SS and CPT consultation revealed no addition injuries or concerns.

Ribs

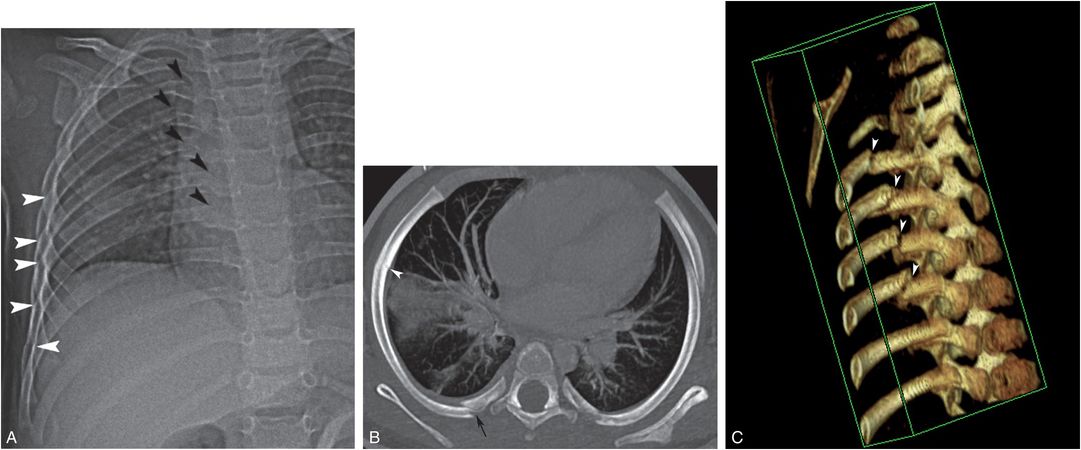

The subject of rib fracture has been covered in detail in Chapter 5. It is clear that rib fractures in otherwise normal infants and young children are highly associated with abuse, but rib fractures are occasionally seen with high energy accidental mechanisms. Since fractures near the costovertebral articulations require a specific mechanism of anteroposterior (AP) compression, invocation of a low-energy household fall to explain fractures at this site should be viewed with extreme caution in a normal child. Fractures of the rib neck have however been described in infants and toddlers involved in high-energy motor vehicle accidents (MVAs), and may be explained by biomechanics similar to those occurring in the abusive setting (Figs. 10.11, 10.12) (83–85). Posterior rib fractures (precise location not described) have been reported in a 21-day-old infant after a chiropractic visit where application of manual pressure and use of a “spring-activated device” was employed for colic (86). The authors stated that abuse could not be excluded.

Figure 10.11 Posteromedial accidental rib fractures. A double stroller with a 13-month-old child seated in the front seat was struck on the right side by an automobile at an unknown speed. The child was ejected and landed on the pavement approximately 10 ft away. In the ED, bruising and a femoral fracture were noted. A, AP view of the chest reveals right fourth-to-eighth posteromedial (black arrowheads) and lateral (white arrowheads) rib fractures. B, Oblique axial MIP CT image along the long axis of the rib demonstrates a fracture at the costo-transverse process junction (black arrow). Buckling of the inner cortex of the lateral rib arc (white arrowhead) represents a second site of fracture of the same rib. C, 3D-CT model viewed from the chest interior demonstrates multiple fractures of the posteromedial ribs at the costo-transverse process articulations (white arrowheads). (With permission from Bixby SD, Abo A, Kleinman PK. High-impact trauma causing multiple posteromedial rib fractures in a child. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2011;27:218–19.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree