Disorders of the Groin and Hip

Groin Pain

Introduction

Normal Anatomy

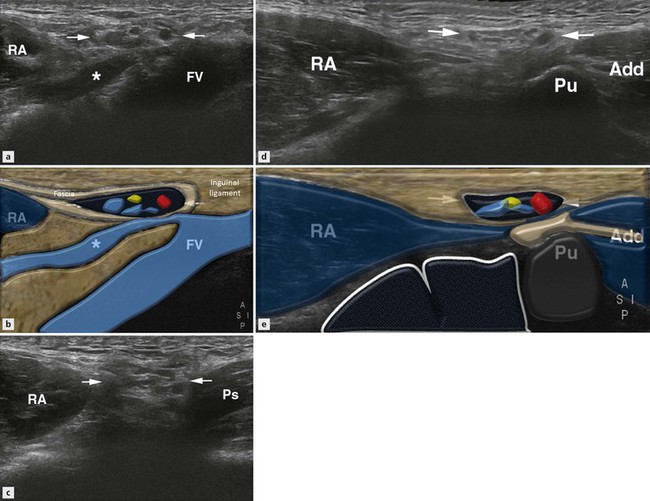

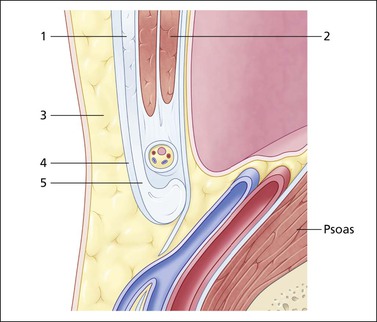

The inguinal canal allows the passage of vessels, nerves, lymphatics and the spermatic cord (round ligament in females) from within the abdomen to the external genitalia. The posterior wall of the canal is formed by the muscle, aponeurosis and fascia of transversus abdominis and also part of the internal oblique. The anterior canal wall is formed from the fascia of the external oblique muscle (Fig. 17.1). The deep (internal) inguinal ring is a defect within the transversus abdominis fascia that allows the contents of the inguinal canal to leave the abdomen and enter the canal proper. The canal then extends obliquely, medially and inferiorly towards the pubic crest where the superficial (external) inguinal ring, a defect in the external oblique fascia, allows the contents to leave the canal (Fig. 17.2). Superficial to the canal is subcutaneous fat and skin, whereas the iliopsoas muscle lies deep to it on its medial aspect and the external iliac vessels pass on the lateral aspect as they enter the thigh. The peritoneum and small bowel lie posterosuperiorly (Figs 17.1 and 17.2).

Figure 17.1 Sagittal section through the lower oblique muscles and inguinal canal. The oblique muscles with external oblique (1) anteriorly and transversus abdominis (2) posteriorly lie superior to the canal and spermatic cord. The subcutaneous fat (3) and deep fascia (4) lie anterior and blend with the external oblique fascia which inferiorly forms the inguinal ligament (5). The psoas muscle and femoral vessels run deep to the canal with the transversus abdominis fascia and peritoneum lying posteriorly and superiorly.

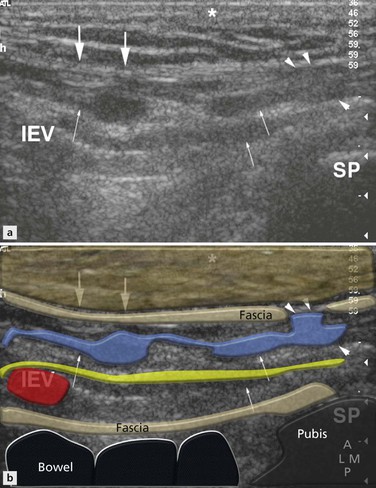

Figure 17.2 Normal right inguinal canal, transverse sonogram. The IEVs lie medial to the internal ring. The thick echogenic inguinal ligament (large arrows) lies anteriorly, deep to the subcutaneous fat (*). Multiple tubular structures are seen (small arrows) passing medially towards the symphysis pubis (SP) and passing through the external ring where a defect (arrowheads) in the inguinal ligament can be visualized.

Examination Technique and Normal Ultrasound Appearances

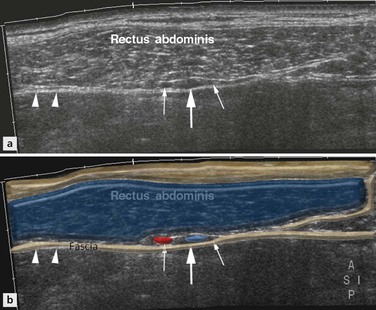

Long Axis View

There are two main methods for visualizing the epigastric vessels, the landmark for assessing the deep ring on dynamic examination. The first method is to scan the rectus abdominis muscle transversely and identify the inferior epigastric vessels (IEVs) within the rectus sheath on its deep aspect (Fig. 17.3). By continuous scanning in the transverse plane the vessels can be followed inferiorly as they sweep to join the external iliac vessels. However, in obese patients with lax musculature, although it is relatively easy to identify the vessels deep to rectus abdominis, it is difficult to continuously follow them because of the patient’s body habitus. Therefore, another technique is to begin with the femoral vessels in the transverse plane and move cranially until the epigastric vessels are seen at their origin and are beginning to pass medially. However, at this point, because the actual course of the inguinal canal is in the transverse oblique plane, the transducer should also be oblique by rotating the medial aspect of the transducer inferiorly.

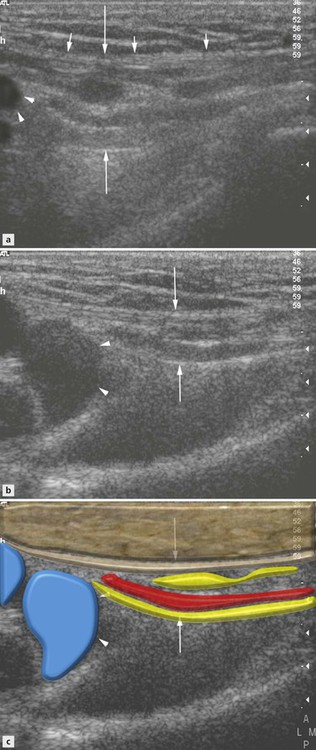

In this position a longitudinal image of the canal is obtained, which includes the epigastric vessels, femoral vessels and proximal inguinal canal. The inguinal ligament is seen as an echogenic line deep to the subcutaneous fat blending with the deep fascia (Figs 17.2 and 17.4). Deep to the ligament are multiple hyperechoic and hypoechoic linear structures (representing vessels, nerves and cords) within the canal. Their prominence is variable and they pass medially to exit the canal through the external ring (seen as a defect of the inguinal ligament) (Figs 17.2 and 17.4). Depending on body habitus the amount of fat within the canal will also vary. Deep to the canal lies the psoas muscle, but echogenic peritoneum and hypoechoic bowel (and a varying amount of preperitoneal fat) lie posterosuperiorly (Figs 17.1 and 17.5).

Occasionally the venous structures within the canal can also distend but again this is quite variable.

It is important to instruct the patient to perform the Valsalva manoeuvre slowly (i.e. not cough) and to ensure that transducer pressure is not applied too firmly otherwise any potential hernia will be maintained in reduction.

If the patient finds this difficult then blowing hard with the fist against their lips will produce the same effect.

Short Axis View

The canal should then be assessed in its short axis, which is the anatomical sagittal plane (Fig. 17.1). To primarily obtain this view a sagittal image of the hip is obtained. The probe is then moved medially to the external iliac/femoral vessels and longitudinally to view the IEVs as they arise and begin to pass superiorly towards rectus abdominis (Fig. 17.5A). At this point the transducer should be moved slightly more medially to come off the epigastric vessels. The short axis of the inguinal canal with its hypoechoic tubular contents can now be visualized with peritoneum and bowel posterosuperiorly (Fig. 17.5). On straining in a normal subject, there may be slight dilatation of the vessels within the canal and the bowel should move towards the canal but should not completely efface or enter the canal (Fig. 17.6).

Figure 17.6 Normal inguinal canal, sagittal sonograms medial to the IEVs. (A) At rest, oval shaped inguinal canal (large arrows) with posterosuperiorly echogenic peritoneum (small arrow). (B, C) On straining, the echogenic peritoneum (small arrow) and hypoechoic bowel push inferiorly and anteriorly, compressing the inguinal canal.