- •

Heart size, cardiothoracic area ratio

- •

Heart rhythm

- •

Degree of displacement of the tricuspid valve

- •

Effective right atrial and right ventricular size

- •

Degree of tricuspid regurgitation

- •

Nature and size of the patent foramen ovale

- •

Size and patency of the right ventricular outflow tract, with particular attention to the relationship between the displaced tricuspid valve leaflet and the outflow tract

- •

Appearance of the pulmonary valve, whether it opens in systole or not, and whether there is any pulmonary insufficiency

- •

Direction of flow within the ductus arteriosus

- •

Left ventricular outflow tract obstruction

- •

Branch pulmonary artery size; qualitative assessment of lung volumes

- •

Ventricular function, left and right ventricle

- •

Presence or absence of pericardial effusion, pleural effusions, or hydrops

Anatomy and Anatomical Associations

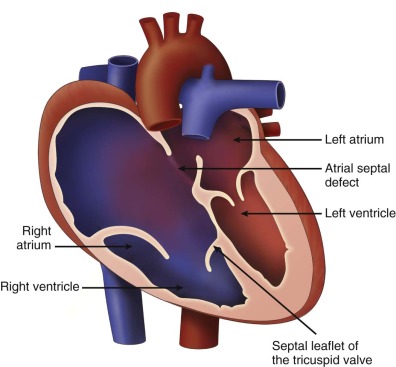

Ebstein’s anomaly of the tricuspid valve (TV) is an abnormality in which there is inferior displacement of the attachments of the septal leaflet of the TV relative to the annulus. It is to be distinguished from a similar anomaly called tricuspid valve dysplasia. In TV dysplasia, the TV attachments are not displaced, although the leaflets are markedly thickened with variable degrees of incompetence. TV dysplasia encompasses a group of diagnoses in which the TV is structurally abnormal, is severely regurgitant, and is not Ebstein’s anomaly. There is no “atrialization” of the ventricle, and right ventricular structure is relatively normal. In both TV dysplasia and Ebstein’s anomaly, the TV leaflets are often grossly malformed and rudimentary in appearance ( Figure 26-1 ). In both of these anomalies, there can be severe tricuspid regurgitation and massive cardiomegaly.

In Ebstein’s anomaly, the septal and inferior leaflet may be tethered to the surface of the right ventricle (RV). The anterior leaflet is normally attached at the TV annulus and appears large and curtain-like, extending to the free wall of the ventricle or to the septum–moderator band complex. Chordae of the anterior leaflet are shortened or absent. With valve closure, the valve leaflets may not adequately coapt, resulting in varying degrees of tricuspid regurgitation. The effective inlet orifice of the TV may be small, leading to varying degrees of functional tricuspid stenosis. The portion of the RV superior to the effective orifice of the TV becomes thin walled and atrialized. With severe tricuspid regurgitation, the atrialized RV and right atrium (RA) dilate massively, leading to severe cardiomegaly, which may compromise lung development. The ventricular septum is frequently abnormal. With marked right ventricular dilation, the ventricular septum may bow into the left ventricular outflow tract, compromising left ventricular function and limiting cardiac output. This ultimately places the fetus at risk for the development of hydrops fetalis.

Atrial septal defects or interatrial communications are present in approximately 90% of patients with Ebstein’s anomaly, which leads to right-to-left shunting and variable degrees of cyanosis postnatally. Corrected transposition of the great arteries may be associated with a left-sided Ebstein’s anomaly of the TV. Right ventricular outflow tract obstruction is frequent. Fibrous subpulmonary stenosis may be present if the orifice of the TV becomes so displaced that it opens just underneath the pulmonary valve. “Functional” pulmonary atresia can be seen in over 50% of infants. This is a phenomenon in which the pulmonary valve leaflets have the anatomical potential to open but do not do so owing to the inability of the RV to generate an opening force to counter distal, pulmonary resistance. Anatomical “true” pulmonary atresia may be seen in over 20%. In the neonate, cardiomegaly secondary to right atrial dilation may compromise lung development, leading to pulmonary hypoplasia. Left-sided abnormalities can also occur. Mitral valve abnormalities, subaortic stenosis, bicuspid aortic valve, and coarctation have been described in association with Ebstein’s anomaly. Ventricular septal defects and tetralogy of Fallot have also been described, but these are extremely rare.

Myocardial abnormalities may be present in Ebstein’s anomaly. In Uhl’s anomaly, a severe form of Ebstein’s anomaly, myocytes fail to develop within the RV. The right ventricular free wall appears thin, translucent, and parchment-like. In the absence of myocytes, the right ventricular free wall fails to contract. Left ventricular dysplasia, resembling noncompaction, has been reported in Ebstein’s anomaly. Finally, the presence of muscular bridges behaving as electrophysiological bypass tracts places the fetus at risk for arrhythmia. Approximately one third of patients with Ebstein’s anomaly have one or more accessory pathways, predisposing them to supraventricular tachycardia. Ventricular tachycardia is less common, but also reported, in particular in those with myocardial disease. Extracardiac anomalies are rare, but skeletal anomalies and chromosomal abnormalities, especially trisomy 13, have been reported.

Frequency, Genetics, and Development

Ebstein’s anomaly of the TV occurs in approximately 5.2 cases per 100,000 live births and accounts for less than 1% of all cases of congenital heart disease. Most cases are sporadic. Familial Ebstein’s anomaly is rare, although mutations in the cardiac transcription factor NKX2.5 and deletions in 10p13-p14 and 1p34.3-p36.11 have been reported. Maternal lithium exposure can rarely lead to Ebstein’s anomaly in the fetus. In the Baltimore-Washington Infant study, additional risk factors for Ebstein’s anomaly included twin pregnancies, those with a family history of congenital heart disease, and maternal exposure to benzodiazepines. The presumed embryology of Ebstein’s anomaly is incomplete delamination of the TV leaflets from the RV, although the precise mechanism is incompletely understood.

Prenatal Physiology

Fetal physiology is dictated by the severity of the Ebstein’s anomaly or the severity of the TV dysplasia. With mild forms of the disease, the fetus is asymptomatic. However, with severe tricuspid regurgitation and marked atrialization of the RV, there can be massive cardiomegaly composed primarily of a dilated RA and RV. Right ventricular systolic function may become compromised with decreased forward flow across the right ventricular outflow tract. With compromised systolic pump function and decreased effective forward flow across the right ventricular outflow tract, the RV may not be able to generate an adequate pressure to open the pulmonary valve, leading to “functional” pulmonary atresia. The pulmonary arteries are then perfused via retrograde (aorta–to–pulmonary artery) flow through the ductus arteriosus. With severe tricuspid insufficiency, right-to-left shunting across the patent foramen ovale increases as RA wall stress increases with RA dilation. Cardiac output is maintained by augmentation of left ventricular stroke volume, up until the left ventricle itself is affected either (1) by compression from the dilated right-sided structures or (2) secondary to ventricular septal dysfunction and altered left-sided myocardial mechanics. A nonrestrictive interatrial communication must be present to maintain cardiac output through to the left side of the heart. Indeed, the presence of a restrictive patent foramen ovale has been associated with hydrops fetalis and fetal demise. With massive dilation of the right side of the heart, lung development may become compromised. The combination of severe tricuspid regurgitation, pulmonary atresia, and lung hypoplasia predicts a particularly poor prognosis for extrauterine life.

Prenatal Management

Prenatal counseling is dictated by the severity of the anomaly. In the past, it was believed that all forms of Ebstein’s anomaly diagnosed in the fetus were severe and, hence, boded for a poor outcome. However, in the current era, detection capacity of fetal echocardiography has improved such that the full spectrum of the disease ranging from mild to moderate to severe cases can be seen. Careful prenatal echocardiographic analysis can help distinguish these types.

Quantifying the degree of RA dilation and RV atrialization is one way to assess severity of the Ebstein’s anomaly. Celermajer and coworkers developed an index, which is a ratio of the sum of area of the RA and any atrialized portion of the RV to the combined area of the functional RV and left side of the heart. The greater this ratio, the greater is the degree of atrialization of the RV and RA size, and the worse the prognosis. Andrews and colleagues published echocardiographic features associated with increased mortality after birth for TV malformations diagnosed during fetal life. These included increased cardiothoracic area ratio greater than 0.65, Celermajer index greater than 1.5, reduced or absent pulmonary valve flow, retrograde flow in the ductus arteriosus, and a right-to-left ventricular cavity ratio greater than 1.5. Fetuses with hydrops fetalis or arrhythmia had particularly poor prognoses, with a high likelihood for intrauterine or neonatal death. In the absence of hydrops fetalis, fetuses with Ebstein’s anomaly without cardiac failure tolerate vaginal delivery well. However, premature delivery via cesarean section for the presence of hydrops fetalis is associated with a high risk of neonatal death. In severely affected fetuses with significant right ventricular outflow tract obstruction and reversal of flow in the ductus arteriosus, prostaglandin infusion should be commenced at birth.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree