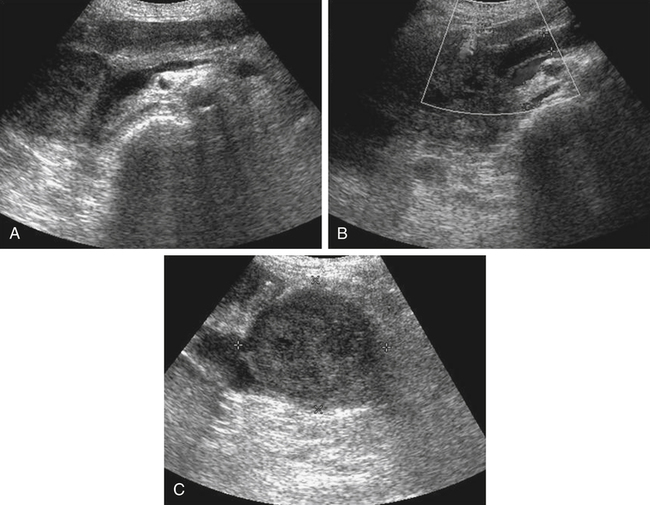

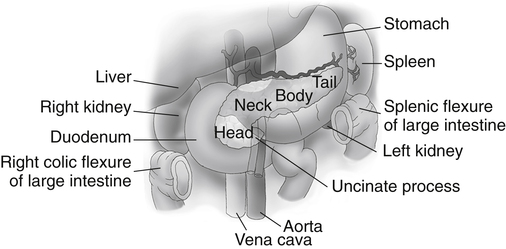

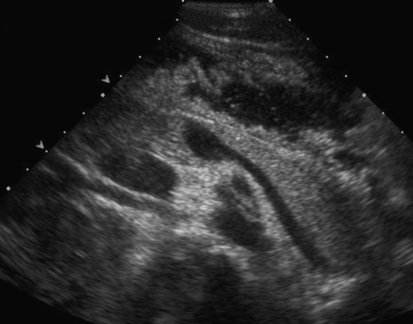

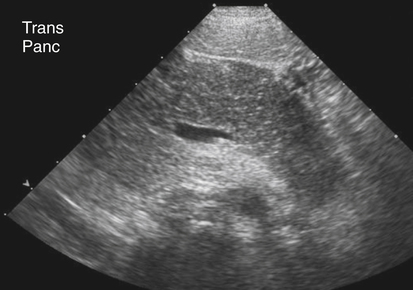

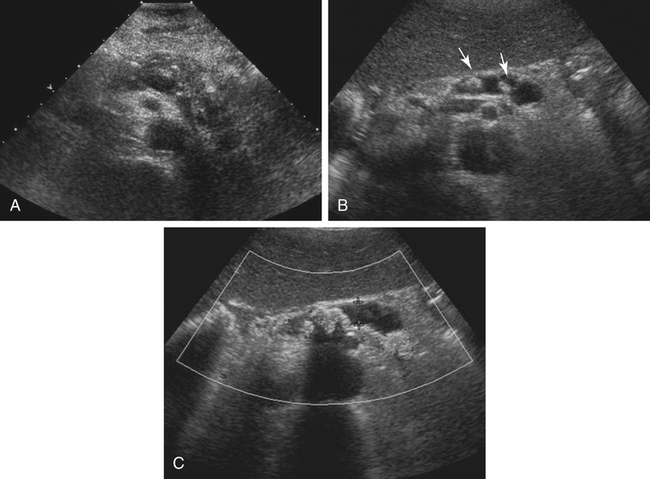

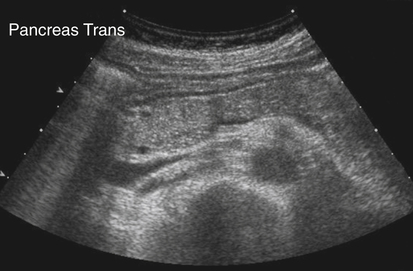

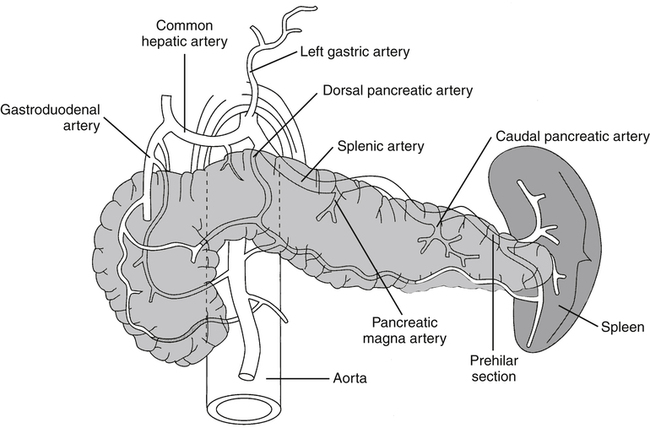

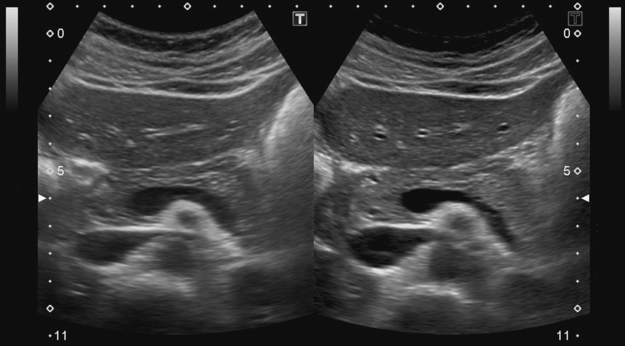

• List several causes of epigastric pain not associated with pancreatic disease. • Describe the normal sonographic appearance of the pancreas and surrounding structures. • Describe the sonographic appearance of common inflammations of the pancreas. • Describe the sonographic appearance of common benign and malignant neoplasms of the pancreas. • List the risk factors associated with various diseases of the pancreas. • Identify pertinent laboratory values associated with specific diseases of the pancreas. The pancreas is a retroperitoneal organ that lies in the anterior pararenal space of the epigastrium. The entire pancreas is contained between the C-loop of the duodenum and the splenic hilum. The parts of the pancreas include the head, uncinate process, neck, body, and tail (Fig. 4-2). A normal adult pancreas is approximately 12 to 15 cm in length. A normal pancreatic duct may be visualized at a measurement of 2 mm or less. The lie of the pancreas in the epigastrium is transverse yet slightly oblique, with the head located more inferior than the tail. The pancreas is a nonencapsulated organ, so the borders are indistinct on sonography. The sonographer must have a thorough understanding of the surrounding vasculature to aid in the detection of the pancreatic boundaries (Fig. 4-3). The sonographer must also appreciate the portions of the gastrointestinal tract that surround the pancreas and make visualization difficult. The fundus of the stomach lies superior to the pancreatic tail. The body of the stomach lies anterior to the pancreatic tail. The pylorus lies anterior to the pancreatic body and neck. The superior duodenum (first portion) lies anterior to the pancreatic neck and superior to the head of the pancreas. The descending duodenum (second portion) lies lateral to the head. The horizontal duodenum (third portion) lies inferior to the pancreatic head. The ascending duodenum (fourth portion) lies inferior to the body of the pancreas. The transverse colon lies anterior and inferior to the entire length of the pancreas (Fig. 4-4). Identification of the various portions of the gastrointestinal tract during scanning allows the sonographer to change the patient position to move obscuring bowel away from the pancreas. Harmonics may enable the sonographer to optimize visualization of the pancreas, especially in technically difficult cases. Harmonic imaging is based on the concept that an ultrasound pulse interacts with tissue, and echoes are created at the original or fundamental frequency along with echoes at multiples of the original frequency (i.e., a 2-MHz pulse generates echoes at 2 MHz, 4 MHz [second harmonic], 6 MHz, , 8 MHz ). Conventional ultrasound listens to the fundamental frequency and ignores the harmonic frequencies. Tissue harmonic imaging typically uses the second harmonic frequency for improved image clarity. Harmonic imaging in the abdomen may also reduce image artifacts, haze, and clutter, and significantly improve contrast resolution (Fig. 4-5). If the pancreatic tail is the primary area of interest, the sonographer or physician may elect to use an oral contrast agent to complement the study. A cellulose suspension should remain in the stomach for an adequate period to provide an acoustic window for better visualization of the pancreatic tail. Alternatively, distilled water can be used to enhance visualization (Fig. 4-6). Although oral contrast agents are not yet used consistently in day-to-day practice, the use of intravenous ultrasound contrast agents shows significant potential. The pancreas may appear normal in the early stage of acute pancreatitis, with no noticeable change in the size or echogenicity of the gland. Once changes become evident, acute pancreatitis may have a diffuse or focal appearance on sonographic examination. The pancreatic duct may be enlarged in either presentation. Diffuse disease causes an increase in size and a decrease in echogenicity from swelling and congestion (Fig. 4-7). The borders of the pancreas may appear irregular. Focal inflammation may be seen as enlargement and a hypoechoic appearance to a specific region of the gland. If focal pancreatitis is present in the pancreatic head, biliary dilation and a Courvoisier’s gallbladder may also be appreciated. The sonographer must carefully evaluate the pancreatic head for adenocarcinoma and the biliary tree for the presence of cholelithiasis and choledocholithiasis as possible causes of pancreatitis. Chronic pancreatitis is defined as recurrent attacks of acute inflammation of the pancreas. Further destruction of the pancreatic parenchyma results in atrophy, fibrosis, scarring, and calcification of the gland. Stone formation within the pancreatic duct is common, and pancreatic pseudocysts develop in 25% to 40% of patients.1,2 Patients generally have progressing epigastric pain. Jaundice may also be seen in patients with a distal biliary duct obstruction. On sonography, the pancreas generally appears smaller than normal and hyperechoic because of scarring and fibrosis. Diffuse calcifications are the classic sonographic feature of chronic pancreatitis and are usually noted throughout the parenchyma, causing a coarse echotexture (Fig. 4-8, A). Stones may also be visualized within a dilated pancreatic duct (Fig. 4-8, B and C). Associated findings include pseudocyst formation, cholelithiasis, choledocholithiasis, and portal-splenic thrombosis.

Epigastric Pain

Pancreas

Normal Sonographic Anatomy

Pancreatitis

Acute Pancreatitis

Sonographic Findings

Chronic Pancreatitis

Sonographic Findings

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Epigastric Pain