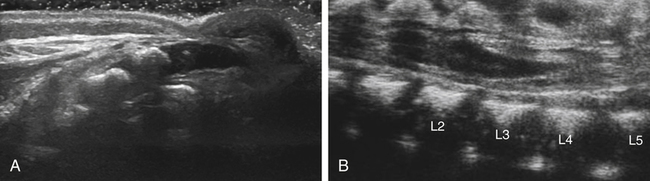

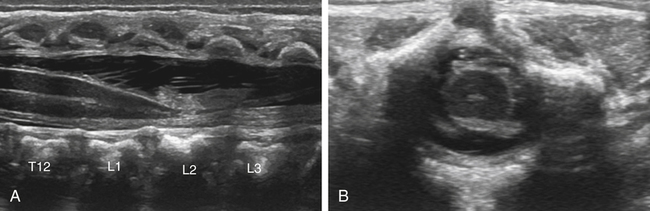

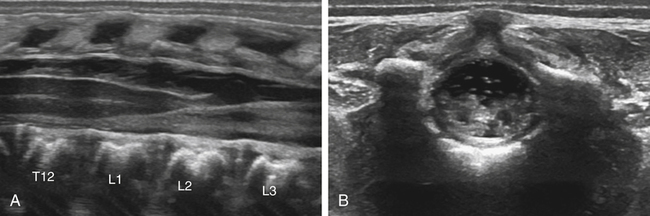

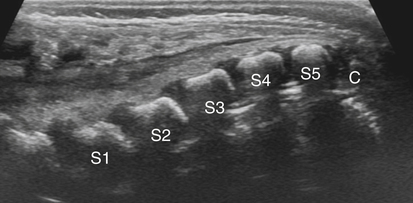

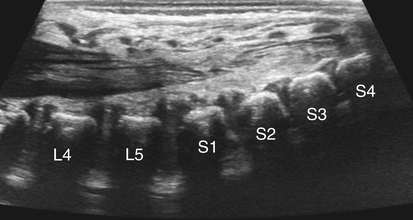

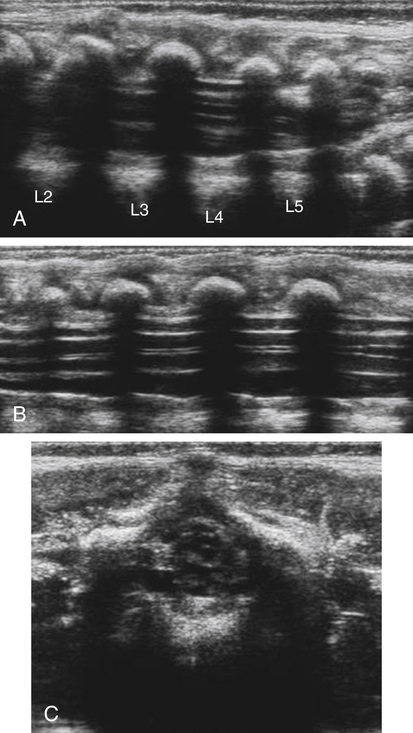

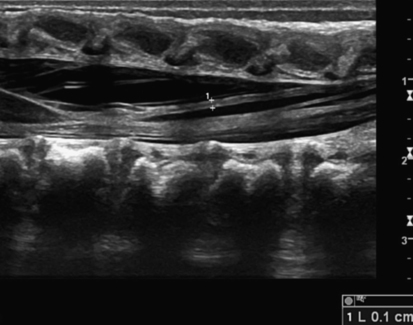

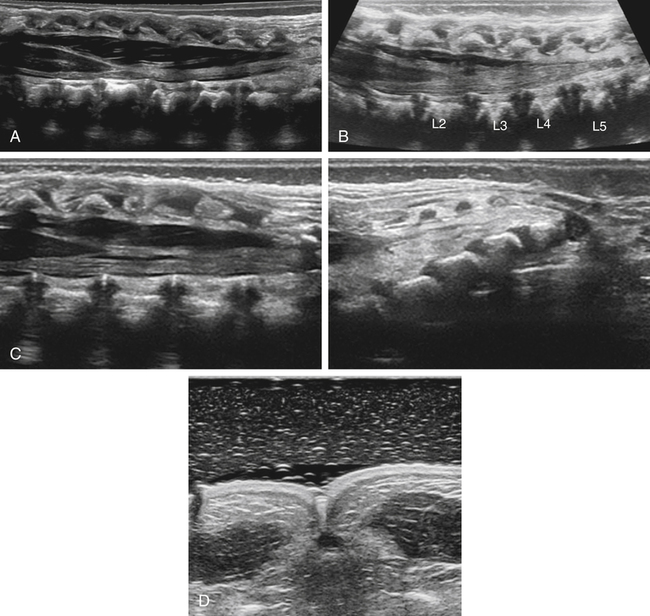

• Recognize the normal sonographic anatomy of the neonatal spine. • Discuss the clinical indications for sonography of the neonatal spine. • Define the sonographic criteria for occult spinal dysraphism. • Recognize specific sonographic features of tethered cord, lipoma, hydromyelia, meningocele and myelomeningocele, and diastematomyelia. Sonography is the preferred imaging modality in cases of suspected abnormal growth or development of the spinal cord and adjacent structures known as occult spinal dysraphism.1 It is a useful tool for evaluating the neonatal spine because of its portability, low cost, noninvasiveness, and lack of radiation. Common clinical indications for neonatal spinal sonography include atypical sacral dimple, palpable subcutaneous sacral mass, hair tuft, skin tag, hemangioma, sinus tract, and skin pigmentation; spinal sonography is also indicated in neonates with multiple congenital anomalies. Congenital spinal dysraphisms can be classified on the basis of the presence or absence of a soft tissue mass and skin covering. Congenital spinal dysraphisms without a mass include tethered cord, diastematomyelia, anterior sacral meningocele, and spinal lipoma. Dysraphisms with a skin-covered soft tissue mass include lipomyelomeningocele and myelocystocele. Dysraphisms with a back mass but without skin covering include myelomeningocele and myelocele. The most common request for spinal sonography is to search for occult tethered cord. This chapter discusses the clinical and sonographic findings of tethered cord and other spinal dysraphisms. On a sonogram, the spinal cord appears hypoechoic with an echogenic central canal. The cord is centrally positioned within the spinal canal. The echogenic nerve roots demonstrate oscillation with respiration or infant movement. The tip of the conus medullaris normally tapers and is positioned at the level of L2 (Fig. 33-2, A). The filum terminale is normally echogenic and measures 2 mm or less in thickness (Fig. 33-3). The spinal cord should remain round in the axial plane through the thoracolumbar region (Fig. 33-2, B). The main purpose of neonatal spine imaging for tethered cord is the identification of the level of the conus medullaris, which should be located above the interspace of the second and third lumbar vertebrae (see Fig. 33-2). A low conus medullaris, below the level of L2, should lead the clinician to suspect a tethered cord. To identify the level of the conus medullaris, an understanding of the normal spinal anatomy is essential. The normal spinal cord in the longitudinal plane is visualized between the posterior vertebral processes as an elongated hypoechoic structure surrounded by anechoic cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (see Fig. 33-2). The cord contains one or two echogenic linear structures, known as the central echo complex. The spinal cord tapers at the caudal end, resembling the end of a carrot. Surrounding and distal to the conus medullaris, the echogenic distal nerve branches, known as the cauda equina (“horse’s tail”), are visualized (Fig. 33-4). A normal spine demonstrates pulsations of the cauda equina during real-time sonographic evaluation. The sonographic evaluation is usually performed with the infant in the prone position and the spine flexed; this may be accomplished by extending the infant over a rolled sheet or pillow. A high-frequency, linear transducer is preferred because a larger transducer footprint is needed to visualize adequately multiple vertebrae along the longitudinal axis. When available, extended field of view, virtual convex, or split-screen imaging (Fig. 33-5, A-C) can also be used to maximize the display of the spine. The neonatal spine should be scanned in both sagittal and axial planes. If a cutaneous dimple is present, a stand-off pad or a thick layer of gel should be used to determine whether the dimple is part of a sinus tract extending from the skin to the spinal cord (Fig. 33-5, D). When scanning the spine, it is recommended to initiate the scan in the sagittal plane, at the level of the sacrococcygeal region. The sacral vertebral bodies, which have begun to ossify, are easily seen. The coccyx appears hypoechoic because it is still cartilage (Fig. 33-6). The sonographer can identify the relevant anatomy by counting the sacral vertebral bodies. The vertebral level is determined by counting down from the 12th rib and confirmed by counting up from S1, the L5-S1 junction, or the tip of coccyx. The first sacral body can be identified because of its posterior angulation (Fig. 33-7). If the vertebral level is unclear, correlation with radiographs (possibly with a marker) may help. The tapering tip of the conus medullaris (see Fig. 33-2, A) should be identified at the level of L2; a normal conus medullaris tip terminates at the L2 level. After scanning in a sagittal plane, the spinal cord should be imaged in the axial plane and scanned from the level of the coccyx to the level of L1. The transverse cord in the lumbar region appears rounded, and the central echo complex appears as echogenic dots (see Fig. 33-2, B). The movement of the filum and cauda equina can be documented with a cine loop or with M mode. The imaging diagnosis of tethered spinal cord is distinct from the clinical diagnosis of tethered cord syndrome. The clinical signs of tethered cord syndrome include pain (especially with flexion), bowel and bladder dysfunction, weakness, sensory changes, gait abnormalities, and musculoskeletal deformities of the feet and spine such as clubfoot and scoliosis. Cutaneous stigmata signifying an underlying congenital defect of the spinal cord also are common.2 Over time, the term “tethered cord” has been used interchangeably to include both imaging and clinical findings. Tethered cord is now defined as an abnormal attachment of the spinal cord to the tissues that surround it.2 A tethered cord may be suspected when cutaneous markers are identified on visual inspection of the infant, including sacral dimple. High-risk, atypical dimples are greater than 5 mm in diameter and greater than 2.5 cm above the anus.1,4 Sonographic features of a tethered spinal cord include the low-lying position of the conus medullaris, below the level of L2, and the spinal cord adhered to the posterior wall or dorsal aspect of the spinal canal (Fig. 33-8). Adherence results in reduced or absent nerve root oscillation with patient respiration or movement in real-time scanning that is identified in a normal spinal cord. In older patients, clinical correlation is required because the conus medullaris may be normally positioned but still be tethered (tight filum syndrome). In this situation, assessment of normal nerve root motion at real-time imaging is more important than the level of the conus medullaris.4

Neonatal Spinal Dimple

Normal Anatomy

Sonographic Evaluation

Tethered Cord

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Radiology Key

Fastest Radiology Insight Engine