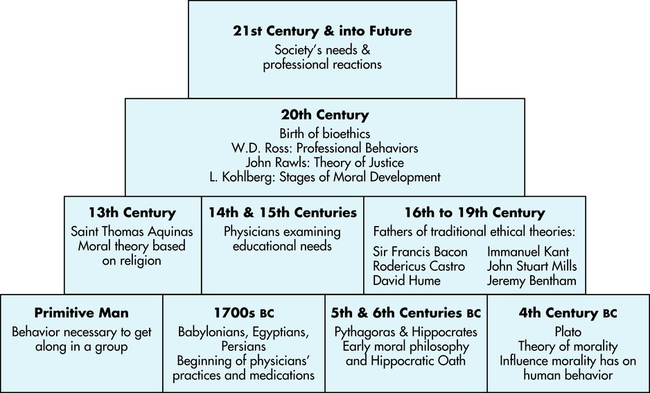

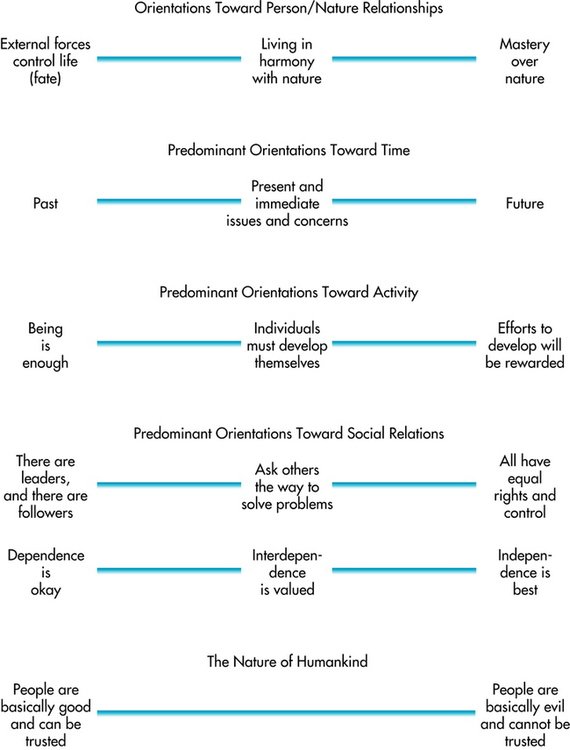

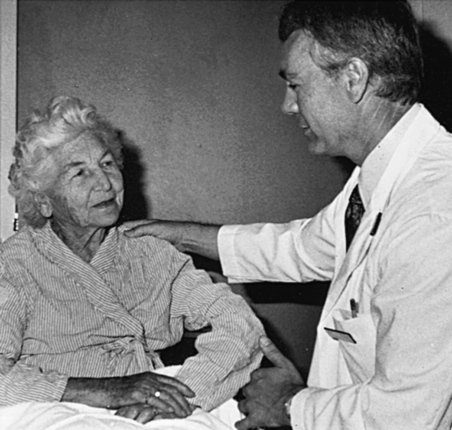

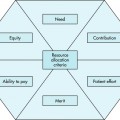

After completing this chapter, the reader will be able to perform the following: • Explore the history of ethics. • Identify three types of values that have an impact on the imaging professional’s ethical decision making. • List and explain ethical schools of thought and models. • Explore the schools of thought and models to choose guidelines acceptable to the reader’s individual style. • List the questions involved in the problem-solving framework. • Define law and describe the three foundations on which it is established. • List the three basic divisions of law and the subdivisions that most frequently have an impact on the imaging professional. • Identify the three phases of a lawsuit, and define the imaging professional’s role in each. • Define risk management and the imaging professional’s role. • Define quality assurance and its implications in the hospital. • Identify additional information needed to minimize risks effectively. Ethics may be defined as the system or code of conduct and morals advocated by a particular individual or group. It is also the study of acceptable conduct and moral judgment.1 Ethics is a system of understanding determinations and motivations based on individual conceptions of right and wrong. It is not determined by strict rules or rigid guidelines, and although it is relatively stable, it can change over time. The preceding description of ethics is broad and general. For the imaging professional, biomedical ethics may be defined as the branch of ethics dealing with dilemmas faced by medical professionals, patients, and their families and friends. Biomedical ethics may also be described as guidelines for proper activities and attitudes toward patients and peers. In this case, biomedical ethics suggests a standard of conduct that is expected of members of the profession. These standards are based on the seven principles of biomedical ethics. They are displayed in Box 1-1 and are discussed later in the text. High ethical standards must be the foundation of professional practice to ensure the recognition of the imaging technologist as a competent health care professional: “The development of a code of ethics is one of the identifying steps in the sequence of the transformation of a semiprofession into a profession.”2 Professional codes of ethics help ensure a high standard of practice. A well-designed code lists the principles and rules defining ethically sound practice. It encourages those within the profession to consider the implications of their actions and educates those outside the profession about the sort of care they may expect. A good code of ethics also serves a regulatory function by specifying a standard of conduct by which all members of a profession must abide. Although many certifying bodies in the imaging and radiation sciences have developed codes of ethics (see Appendix A), unification remains a challenge. The American Society of Radiologic Technologists (ASRT) Code of Ethics considers various aspects of the imaging professional’s role in health care. These areas include conduct, respect, diversity, technical applications, decision making, aid in diagnosis, radiation protection, ethical conduct, confidentiality, and education. The creation of an ethical framework requires critical thinking. Critical thinking has been defined as “purposeful, self-regulatory judgment which results in interpretation, analysis, evaluation, and inference.”3 It is an ethical problem-solving tool that allows the imaging professional to perform the following tasks: • Adequately interpret and analyze ethical theories and models • Evaluate the application of those theories and models to a given situation Critical thinking allows the professional to process personal experience and knowledge and incorporate them into daily decisions. Through critical thinking the professional internalizes and personalizes ethical concepts. Attributes of critical thinkers are listed in Box 1-2. Values determine both personal and professional ethics; therefore ethical questions generally involve conflicts between values. A value is a quality or standard that is desirable or worthy of esteem in itself. Values are expressed in behaviors, language, and the standards of conduct the imaging professional endorses or tries to maintain.5 A person’s daily experiences influence and guide the expression of values. For example, a professional who attempts to maintain honesty with co-workers and patients has honesty as a personal value. Values clarification developed by Louis Rath enables the individual to discover, analyze, and prioritize what he or she has.6 Rath explains that an individual should make choices only after careful consideration of the alternatives. The person should take pride in these choices and be willing to defend them. An example of this might be an imaging professional who has, after careful consideration of personal values, made the choice to become a radiation therapy professional. The individual takes great pride in this decision and is willing to discuss and defend this choice. The imaging professional has based this decision on a desire to enhance the quality of life for patients who may be dealing with life-threatening illnesses. Imaging professionals prioritize their values, creating a hierarchy. For example, an imaging professional who values honesty may also value privacy to a greater or lesser degree. Depending on the way each of these values ranks within the personal hierarchy, the professional may take several different courses of action when faced with a dilemma in which both privacy and honesty are involved. This hierarchy may change over time as a result of life experiences and individual reassessment.7 Values guide and motivate the decisions and choices of imaging professionals, often without their realizing it.8 Because the motivations and actions of others may be based on different hierarchies and different value systems, awareness of individual values improves communication. Imaging professionals should use self-analysis to determine their own values before they begin ethical problem solving, which is discussed later in this chapter. Understanding the values of others and recognizing their importance are important steps in ethical decision making. Imaging professionals must recognize that others’ values are as valid as their own.9 The three basic groups of values are personal values, cultural values, and professional values. Personal values are the beliefs and attitudes held by an individual that provide a foundation for behavior and the way the individual experiences life.9 For example, an imaging professional may personally value timeliness and organization. These values influence the way the imaging professional makes decisions and judgments. Religious convictions, family, political beliefs, education, life experiences, and culture influence the imaging professional’s personal values. Each person’s values differ.10 Values specific to a people or culture are known as cultural values. They may also guide the imaging professional’s decision making because they influence opinions about health care. The value of individual choice may be important to an imaging professional from the United States. An imaging professional from an Asian culture may place more emphasis on the value of elderly people than would some professionals from other cultures.9 Multiculturalism and diversity integrated into the imaging curriculum facilitate discussions of cultural values and their importance to high-quality imaging services (see also Chapter 9). The imaging professional must acknowledge the impact of culture on decision-making processes. Figure 1-2 presents continua of cultural values. Values may conflict with one another, with the imaging professional’s duties, and with patients’ rights. Personal, professional, and cultural values may provide conflicting guidelines.8 The computed tomography (CT) specialist’s value of providing good care for the patient during the examination may conflict with the value of honoring the patient’s right to choose, especially if the patient is hesitant to have the examination. The radiation therapy technologist’s value of carefully giving safe therapeutic doses of radiation may conflict with the patient’s value of relief from suffering. In each of these situations, imaging professionals must identify the values involved in the decision-making process and determine the most important ones. The imaging professional works in a challenging and changing environment. To respond appropriately to the many biomedical ethical dilemmas they will face, imaging professionals must be able to apply the basic concepts of professionalism—an awareness of the conduct, aims, and qualities defining a given profession (Figure 1-3).11 Familiarity with professional codes of ethics and understanding of ethical schools of thought, patient-professional interaction models, and patients’ rights prepares imaging professionals to address future ethical dilemmas. When difficult situations arise, they have already thought through the various courses of action and can respond in keeping with their personal standards of ethics.

Ethical and Legal Foundations

ETHICAL ISSUES

VALUES

Personal Values

Cultural Values

Values in Practice

PROFESSIONALISM

Ethical and Legal Foundations