She had breast implants years ago and now she’s nervous: I wonder if that lump that my doctor feels is related to my implant or if it’s something more serious. What if it’s cancer? Should I take their advice and get a mammogram? What if my implants rupture?

The primary goal of mammography in patients with implants remains the detection of potentially malignant lesions. Cancer detection in the augmented breast can pose unique challenges. Mammography may be hindered by limitations in positioning and compression of the tissue. Women referred because of clinical findings must be evaluated with a wider differential diagnosis in mind: implants and their complications can produce false-positive findings for malignancies, and conversely, breast cancer may be mistaken for implant-related complications.

Breast augmentation is common—11/1000 in one large series. The first sealed breast implant was a silicone gel-filled prosthesis developed and introduced in the early 1960s. Since that time, breast augmentation has become the most commonly performed cosmetic surgery in the United States, and over 389,000 breast augmentation and reconstruction procedures were performed in 2010. About 20% of implant surgeries were performed in breast cancer patients, most commonly for reconstruction following mastectomy.

Mammography, ultrasonography (US), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used to differentiate findings of concern for malignancy from those related to implants, their complications, or their sequelae after rupture or explantation. It is therefore important to be familiar with the terminology and imaging findings related to implants and their complications.

Implant Terminology

Since their introduction, over 240 styles of breast implants and tissue expanders have been introduced by American manufacturers alone. The major differences among implant types relate to the number of lumens, the substances that fill them, and the location of the implant.

Implant Shell

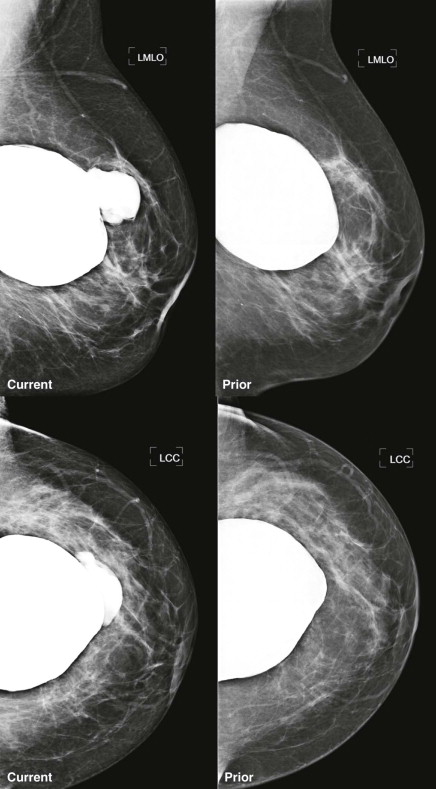

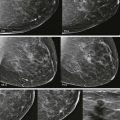

The implant shell (synonyms: elastomer shell, envelope, or membrane) used for both saline- and silicone-containing implants is an elastic, semipermeable membrane made of a solid silicone polymer ( Fig. 19-1 ). The outer surface of shell is textured in some implants to reduce the incidence of implant rotation and capsular contracture. Texturing may cause the outer edge of the implant to appear indistinct on mammography.

Implant Lumens and Contents

Implants almost always have one or two lumens—triple-lumen implants have been manufactured but are rarely seen in practice. Single-lumen implants outnumber the multilumen varieties by a large margin. Implants are filled with either saline or silicone gel ( Fig. 19-2 ). Of breast implants placed in 2010, 60% contained silicone gel and the remainder saline. Double-lumen models usually have an inner lumen filled with silicone and an outer lumen filled with saline. However, the opposite configuration (reverse double lumen) with inner saline and outer silicone as well as silicone-within-silicone implants may also be seen but are very uncommon.

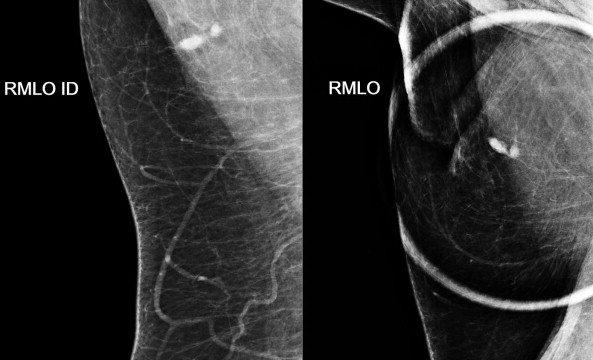

Saline implants have a valve or diaphragm through which fluid can be instilled or removed. An expander implant has a metal valve through which saline can be added over time. These implants are usually placed after mastectomy and exchanged for permanent saline or silicone implants after full expansion. Because of the metallic valve, expander implants are not safe for MRI.

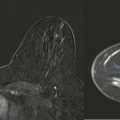

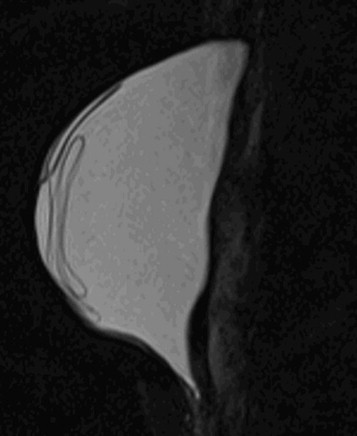

On mammography, silicone is radiopaque but saline is much more radiolucent. The two types can be distinguished on routine mammography and dual-lumen implants may be appreciated if the outer lumen is saline and the inner silicone (see Fig. 19-2 ). On US, saline and silicone implants are normally anechoic. Silicone implants may have strong reverberation artifact even when intact. MRI evaluation of implants is not necessary for saline implant integrity. “Silicone” sequences are typically heavily T2-weighted, often with both fat and water suppression. Silicone will be bright white on these sequences ( Fig. 19-3 ).

Patients who have had direct injection of silicone, paraffin, polyacrylamide gel, or other substances into the breast for augmentation may occasionally be encountered. Silicone injections produce dense masses on mammography, some with peripheral calcifications, and areas of fat necrosis ( Fig. 19-4 ). Paraffin injections can appear initially as masses representing fluid collections and later as masses representing paraffinomas with calcifications and architectural distortion. Direct injection of these substances markedly limits clinical and mammographic evaluation.

Implant Location

Most implants are placed either behind the glandular tissue and anterior to the pectoralis major muscle (subglandular, retroglandular, prepectoral), or between the pectoralis major and minor muscles (subpectoral, submuscular). The terms subglandular and subpectoral will be used in this chapter (see Fig. 19-2 ).

Fibrous Capsule

When an implant is placed, it incites an inflammatory reaction in the surrounding tissues leading to the formation of a fibrous capsule. This may be visible on the mammogram as a thin band of soft tissue immediately adjacent to the implant shell. The fibrous capsule has a smooth inner surface that is closely apposed to the outer surface of the implant shell, creating a potential space between the two. Calcifications often develop within the fibrous capsule typically years after placement of the implant.

Implant Complications ( Box 19-1 )

Mammography, US, and MRI have different strengths and limitations in detecting and characterizing implant complications. Mammographic screening of women with implants will detect some complications in the asymptomatic patient. In one study of 350 women with implants, 16 (5%) had evidence of rupture on screening mammography, including two with bilateral rupture. The decision to evaluate implants with US is usually based on clinical or mammographic findings. MRI is the most accurate imaging modality for determining implant status. The gold standard for determining whether an implant is intact is examination after surgical removal.

- •

Intracapsular rupture

- •

Extracapsular rupture

- •

Silicone granuloma

- •

Distant migration of silicone

- •

Silicone adenopathy

- •

Capsular contracture

- •

Bulge in contour

- •

Herniation through fibrous capsule

- •

Infection

- •

Hemorrhage

- •

Implant migration

Capsular Contracture

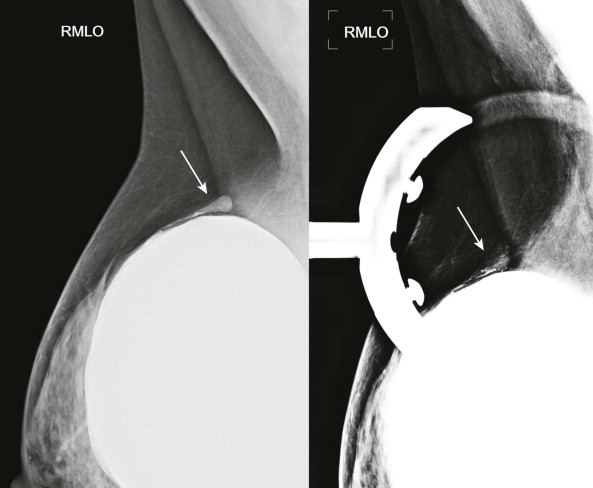

Capsular contracture is the most common complication of implants and is due to contraction of the fibrous capsule around the implant. It can occur with either silicone or saline implants but is most common with silicone implants in a subglandular location. This is a clinical diagnosis in which fibrous tissue displaces or changes the shape of the implant or limits its movement. In its most severe form, the breast becomes hard and there is distortion of the implant. The mammography technologist may not be able to displace the implant, limiting evaluation of the breast parenchyma. On mammography, rounding or distortion of the implant may be seen. Comparison with several previous mammograms may reveal progressive rounding of the implant coinciding with progressive loss of the technologists’ ability to displace it.

Capsular contracture was previously treated by closed capsulotomy. In this procedure, the surgeon manually disrupted the fibrous bands without surgical incision while the patient was under anesthesia. In some women, this converted the problem from a firm, intact implant to a softer, ruptured one. Because of the risk of rupture, this procedure is no longer commonly performed.

Gel Bleed

Many toys are made out of silicone, like the bag of eyeballs at the science museum. They’re really fun to squeeze and play with, but have you ever noticed that your hands are kind of sticky afterward? Just as with those kids’ toys, silicone molecules can pass through the semipermeable implant shell even when the implant is not ruptured. Now you will understand silicone gel bleed. In this process, silicone gel can coat the exterior surface of the shell. This gel can travel, and silicone may appear in axillary lymph nodes even without rupture.

Rupture

The main predisposing factor for rupture is the age of the implant. Rupture may occur spontaneously or be caused by a specific event, including trauma, closed capsulotomy, and complications of surgical or needle biopsy or other interventional procedures. The implant shell can withstand a compression force much greater than is typically used for mammography; rupture during mammography is rare.

Saline Implant Rupture

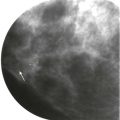

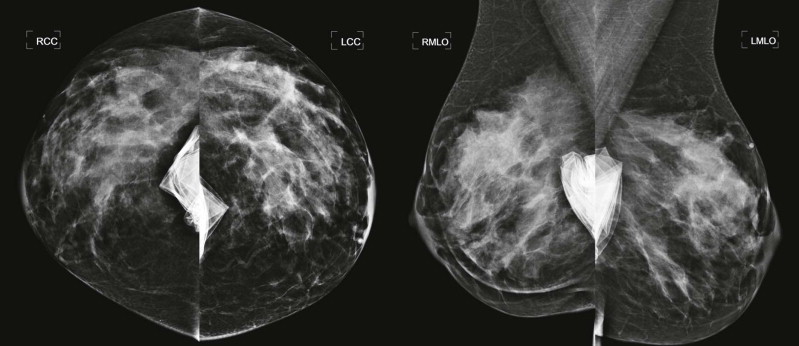

Rupture of saline implants is usually obvious clinically and on mammography. The extraluminal saline is resorbed, and on mammography the implant shell is partially or wholly collapsed ( Fig. 19-5 ), which looks like someone took your wadded-up plastic sandwich bag and stuck it in the back of the breast. You don’t need US or MRI to make this diagnosis!

Silicone Implant Rupture

Diagnosis of silicone implant rupture can be more challenging both clinically and by imaging. There are two types or stages of silicone implant rupture—intracapsular and extracapsular (see Fig. 19-1 ). With intracapsular rupture, the implant shell is disrupted but the silicone is still contained by the fibrous capsule. These patients are typically asymptomatic. With extracapsular rupture, both the implant shell and fibrous capsule are disrupted. These patients may complain of pain or tenderness, palpable nodules, or decreased implant size, but they may also be asymptomatic.

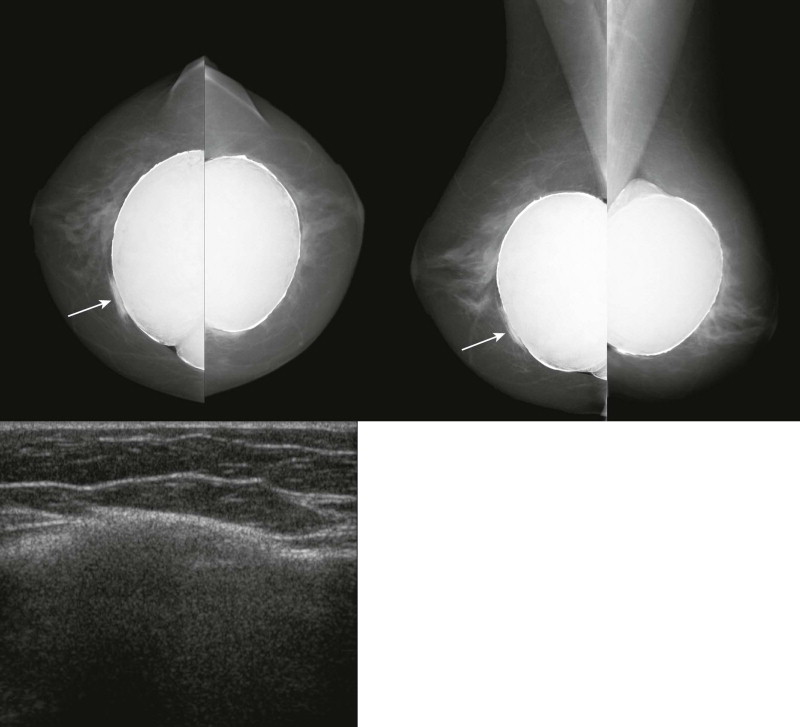

Intracapsular rupture is often not apparent on clinical examination or mammography because the contour of silicone contained by the fibrous capsule is similar or identical to that produced by the intact shell.

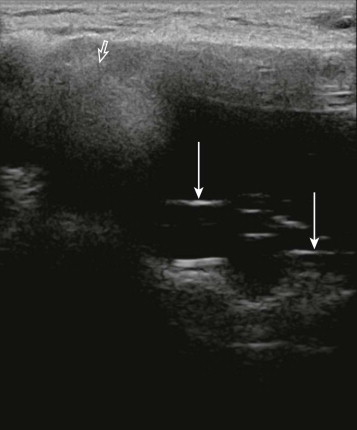

US is not very sensitive or specific in the evaluation of intracapsular rupture, limiting its value in this role. One finding suggestive of rupture are multiple parallel echogenic lines within the sonolucent silicone, creating an appearance known as the “stepladder sign” ( Fig. 19-6 ). Another US finding suggestive but not diagnostic of intracapsular rupture is that of low-level echoes internally, within the silicone gel, which is typically more sonolucent when the implant is intact.

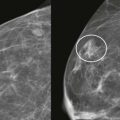

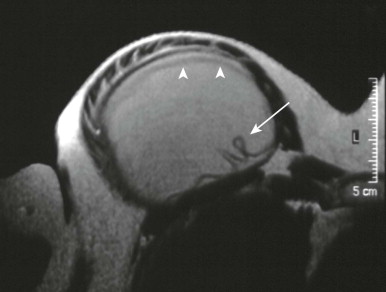

MRI is the most sensitive and specific imaging modality for evaluating implant rupture. In one series, sensitivity and specificity for gross rupture were 98% and 91%, respectively. With intracapsular rupture, MRI shows curvilinear low-intensity signal within the implant, an appearance known as the linguine sign ( Fig. 19-7 ). This appearance can be caused by the elastomer shell floating in the silicone, contained by the fibrous capsule. However, in some cases, the linear signal is not actually the shell but is caused by water mixing with the silicone. This is a moot point because the imaging finding suggests intracapsular rupture whether those linear signals are due to the elastomer shell or water mixing with silicone.

The sensitivity of MRI is lower when only a small amount of silicone has leaked outside the shell but the shell has not collapsed. The subcapsular line sign reveals silicone adjacent to both surfaces of the ruptured shell. The inverted teardrop (also known as the keyhole or noose sign) is another appearance of silicone leakage within a fold in the shell ( Fig. 19-8 ). Rupture of the inner silicone lumen of a double-lumen implant results in mixture of silicone and saline, producing an appearance known as the “salad oil” sign.

Extracapsular rupture is usually a relatively easy diagnosis on any modality. Mammography is quite effective in demonstrating extracapsular silicone because its density is higher than that of breast parenchyma ( Figs. 19-9 to 19-11 ). When interpreting the mammogram, trace the edge of the implant to see if it is smooth. Look for any contour abnormalities and for globules or linear tracking of silicone outside the fibrous capsule. Silicone within breast tissue may form silicone granulomas, and occasionally, silicone may be seen extending into ducts. It may also be visible within axillary lymph nodes ( Fig. 19-12 ) and migrate to more distant sites.