LEARNING OBJECTIVES

1. Invasive ductal carcinoma, not otherwise specified (NOS)

• Clinical features

• Imaging features

• Histology

2. Extensive intraductal component (EIC)

• Definition

3. Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)

4. Tubular carcinoma

• Clinical features

• Imaging features

• Histology

5. Mucinous carcinoma

• Clinical features

• Imaging features

• Histology

6. Medullary carcinoma

• Clinical features

• Imaging features

• Histology

7. Papillary carcinoma

• Clinical features

• Imaging features

• Histology

8. Metaplastic carcinoma

• Clinical features

• Imaging features

• Histology

9. Invasive lobular carcinoma

• Clinical features

• Imaging features

• Histology

10. Lymphoma

• Clinical features

• Imaging features

• Histology

11. Sarcomas

• Primary

• Radiation related

12. Metastatic disease to the breast

13. Metastatic disease to intramammary and axillary lymph nodes

The focus of this chapter is on breast cancers that present with a mass detected on physical examination or with imaging. Invasive ductal carcinoma NOS is the most common type of breast cancer followed in frequency by invasive lobular carcinoma. Also discussed are relatively common variants of invasive ductal carcinoma including tubular, mucinous, papillary, medullary, and metaplastic carcinomas. It is important to emphasize, however, that there are additional variants of invasive ductal carcinoma that, because of their rarity, are beyond the scope of this book and not discussed. They include squamous, apocrine, adenoid cystic, secretory, neuroendocrine, cystic hypersecretory, cribriform, small cell, lipid rich, glycogen rich, and invasive micropapillary carcinomas (1,2).

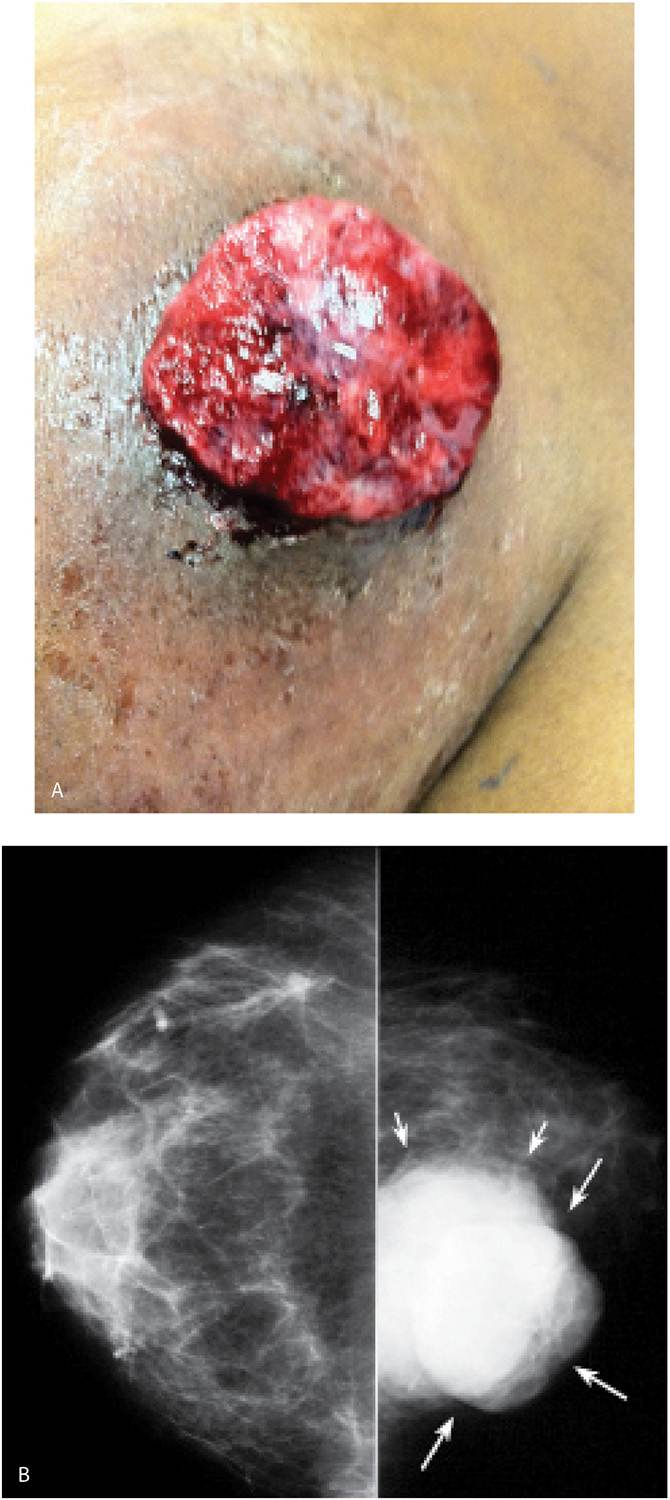

INVASIVE DUCTAL CARCINOMA

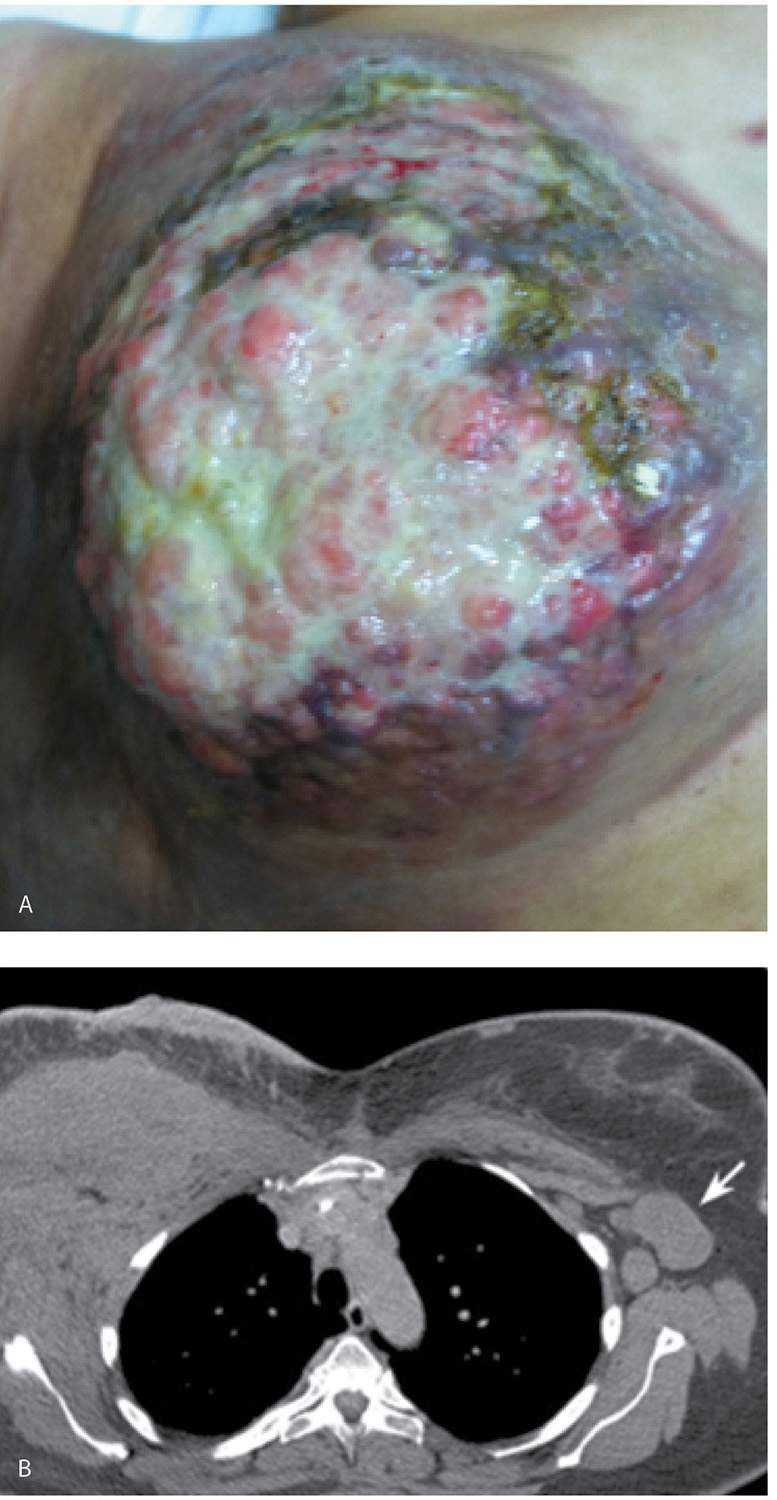

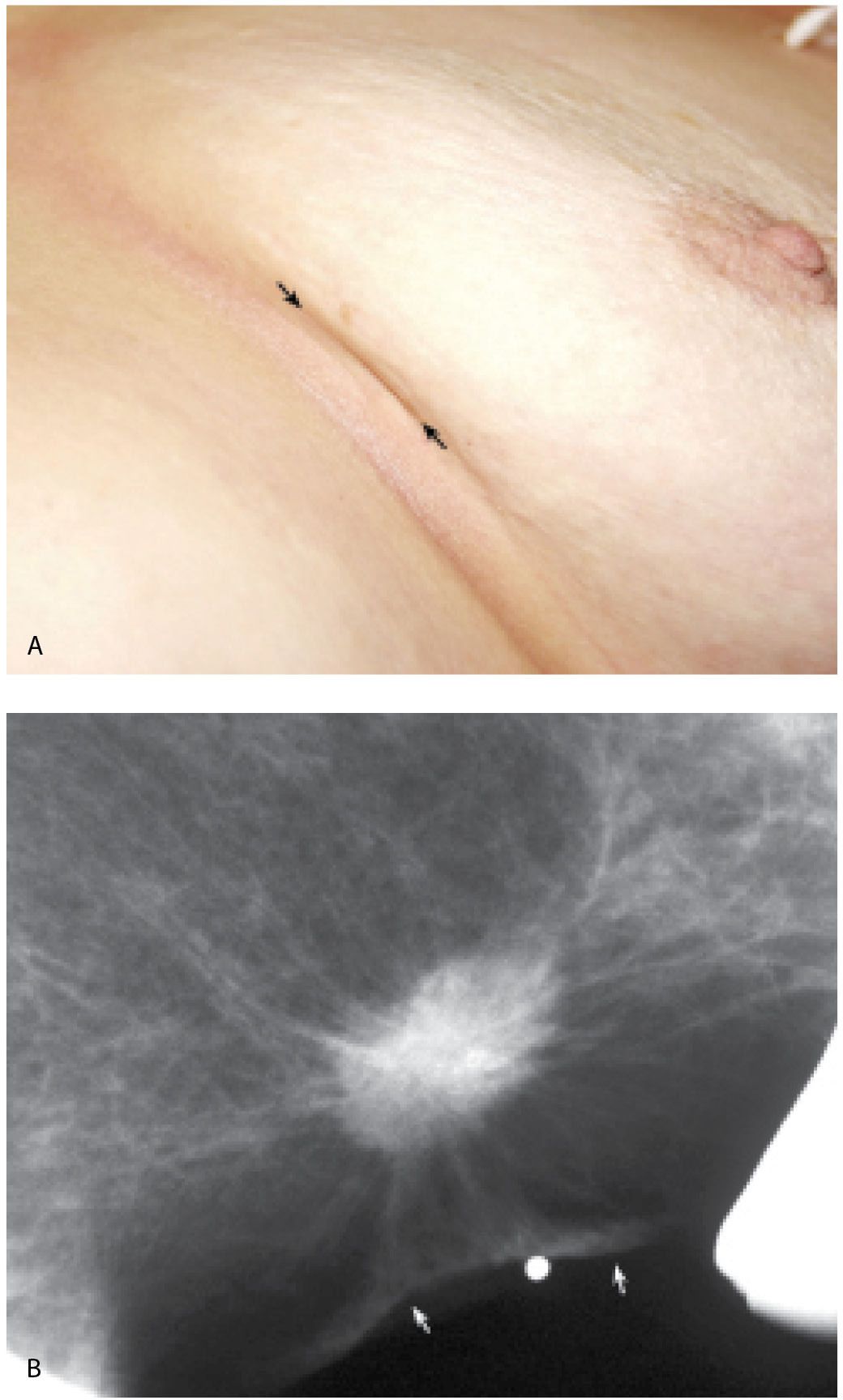

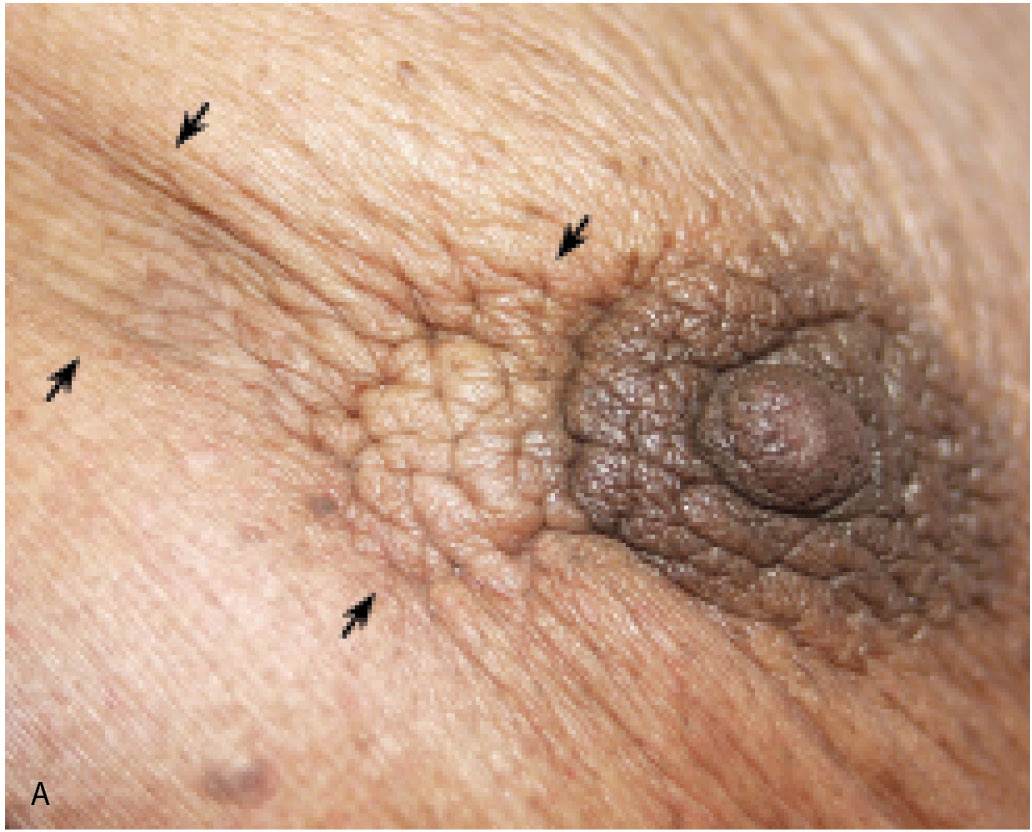

Invasive ductal carcinoma NOS, or no special type, is the most common type of breast cancer representing 65% to 75% of mammary carcinomas (1,2). Depending on the size of the lesion, size of the breast, and proximity of the lesion to the skin, patients can present with a hard, fixed, palpable mass that may cause skin thickening and retraction (Fig. 8.1). If the cancer is in the subareolar area, patients may describe progressive flattening of the nipple, nipple deviation, inversion, or retraction (Fig. 8.2) or changes in the periareolar area (Fig. 8.3). When more advanced, the patient may present with skin ulceration (Fig. 8.4), a mass that protrudes or fungates through the skin (Fig. 8.5), more diffuse breast deformity and ulcerations, (Fig. 8.6) or areas of necrotic tissue focally or more diffusely involving the breast (Fig. 8.7). Localized or more diffuse edematous or erythematous changes (peau d’orange) may be apparent; skin nodules reflecting metastatic disease may be seen in patients with locally advanced breast cancer (Fig. 8.6A). Rarely, patients present with spontaneous nipple discharge, and less than 1% of patients present with metastatic disease to the axilla but no clinically or mammographically detectable primary breast lesion. As discussed in Chapter 5, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI; see Fig. 5.27) is useful in depicting the primary lesion in the breast in this group of patients (3).

FIG. 8.1 • Skin dimpling, invasive ductal carcinoma, NOS, well-differentiated. A: This 77-year-old patient presents with dimpling (arrows) just above the inframammary fold on the left. In some patients, dimpling becomes apparent during positioning and as compression is applied; the technologist is in a unique position to identify skin and nipple changes; any observation should be documented so that the information is available to the interpreting radiologist. B: Spot tangential view at site of skin dimpling. An iso dense oval mass with spiculated margins and associated skin thickening and retraction (arrows) is correlated to the site of clinical concern. (From Cardeñosa G. Breast Imaging [The Core Curriculum Series]. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.)

FIG. 8.2 • Nipple inversion and retraction, focal peau d’orange. Nipple inversion and retraction with slight lateral deviation as well as localized peau d’orange changes (arrows) extending from the areolar margin into the upper outer quadrant of the right breast in a patient with invasive ductal carcinoma. Skin in the lower inner quadrant is normal.

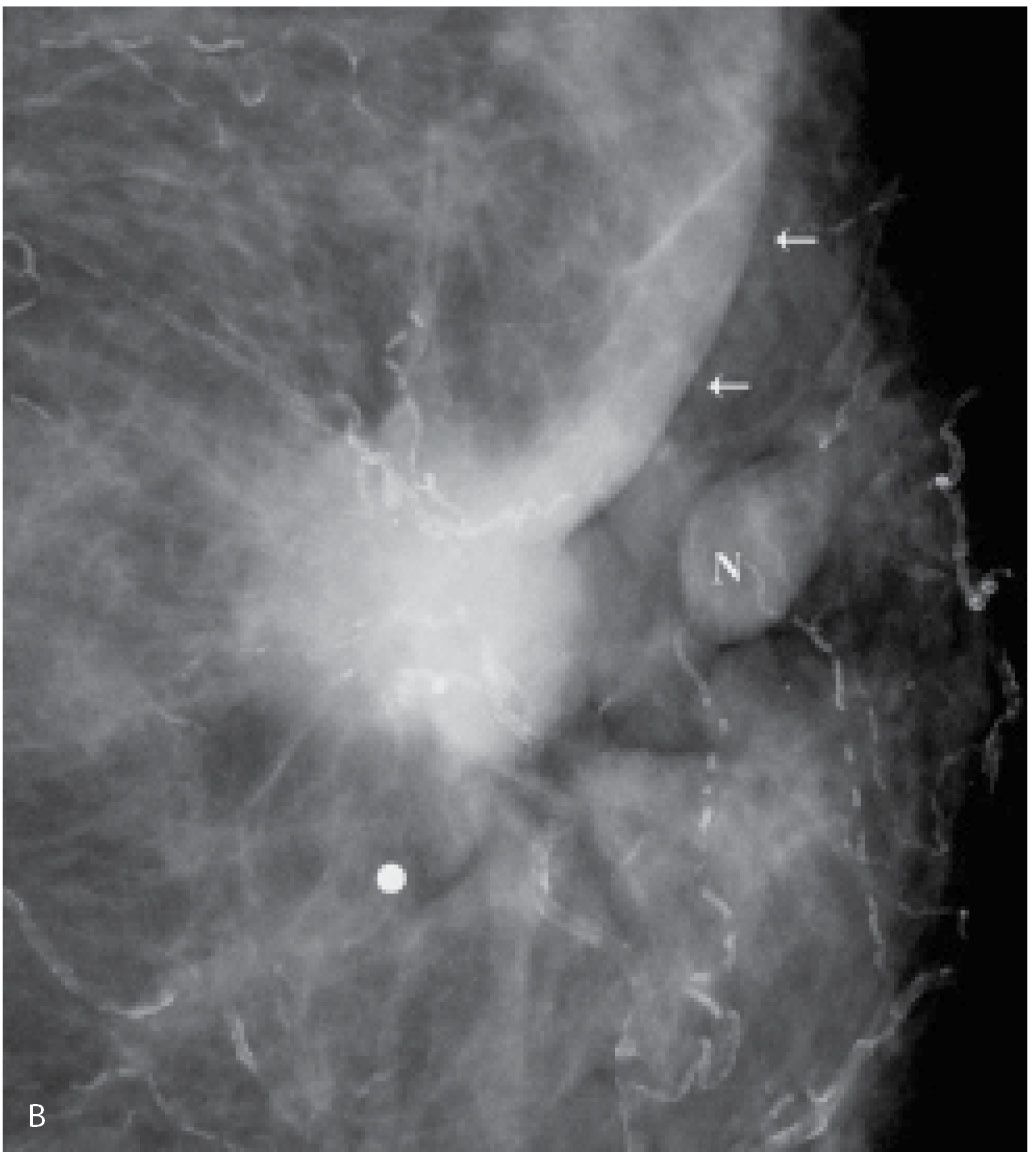

FIG. 8.3 • Skin dimpling and retraction, invasive ductal carcinoma NOS, moderately differentiated. A: Thickening, dimpling, and retraction of the skin (arrows) extending peripherally from the upper central margin of the left areola in a 90-year-old patient. Note slight deviation of the nipple. B: Spot compression view, left breast. A dense, round mass with ill-defined and spiculated margins, associated skin thickening, and retraction (arrows) is imaged adjacent to the left nipple (N). The metallic BB is used to denote the area of clinical concern. Extensive arterial calcification is present. (From Cardeñosa G. Breast Imaging [The Core Curriculum Series]. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.)

With the increasing use of screening mammography, patients with invasive ductal carcinomas are diagnosed before signs of cancer are detected clinically or symptoms have developed. A mass with spiculated margins (Figs. 8.1B and 8.8) is one of the most common presentations in asymptomatic women. Less frequently, invasive ductal carcinoma presents as a round (Fig. 8.9), oval (Fig. 8.10), or irregular mass with indistinct margins, less often, circumscribed margins. Although cancers are more commonly iso to high in density, some are low in density, and as such, the density of a mass alone cannot be used to distinguish benign from malignant masses. Likewise, size alone is not a reliable criterion in distinguishing benign from malignant masses.

FIG. 8.4 • Skin ulceration, invasive ductal carcinoma NOS, moderately differentiated. Skin ulceration (arrow) with surrounding erythema is present in the upper inner quadrant of the right breast in a 78-year-old patient with an underlying hard fixed mass on palpation. (From Cardeñosa G. Breast Imaging [The Core Curriculum Series]. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.)

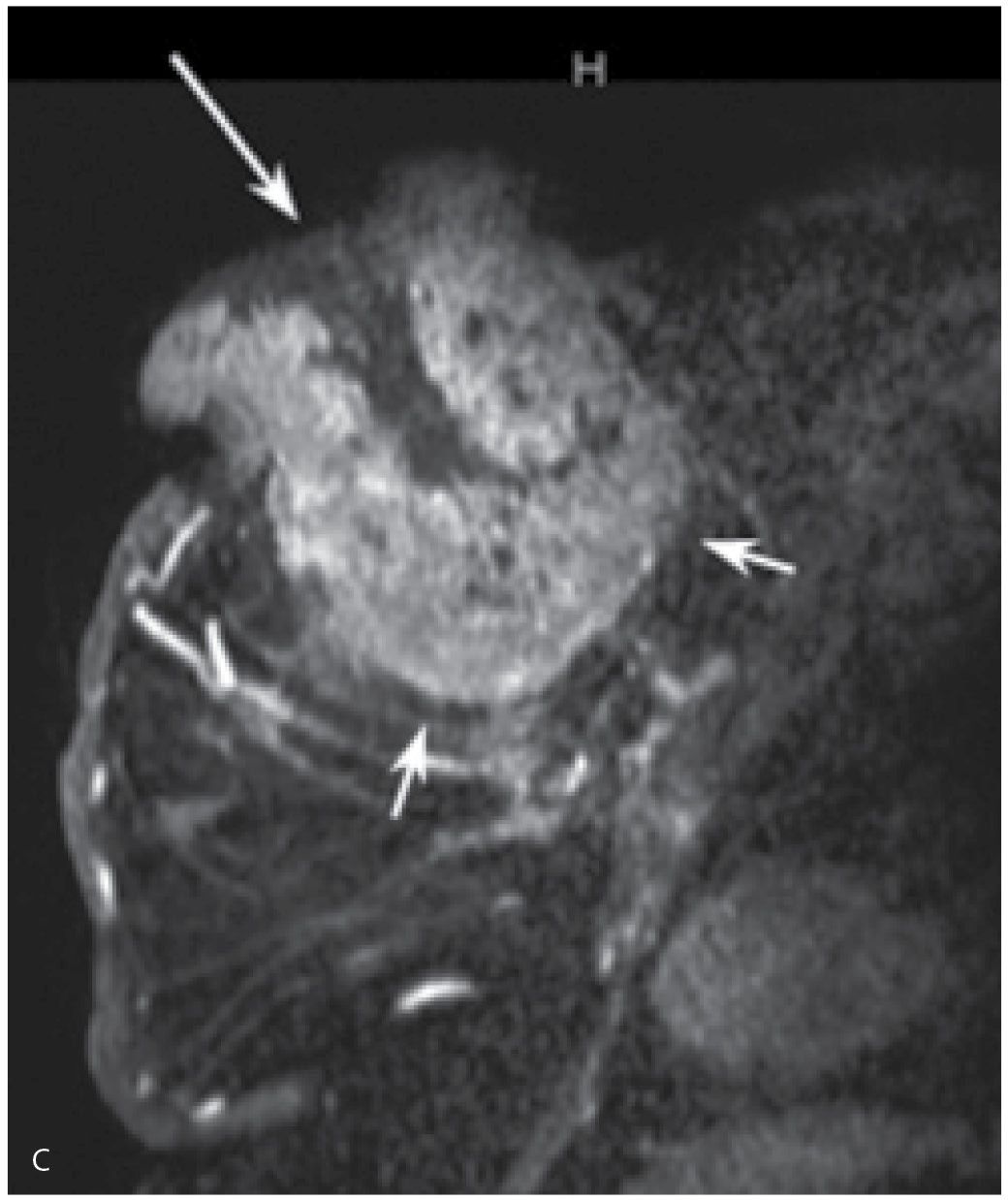

FIG. 8.5 • Fungating mass, invasive ductal carcinoma NOS, high nuclear grade. A: A fungating, necrotic mass is evident in the upper inner quadrant of the left breast in a 54-year-old patient. B: Craniocaudal (CC) views. A dense, round mass with indistinct margins posteriorly (short arrows) is partially imaged medially in the left breast; the portion of the mass that extends beyond the skin (long arrows) is outlined by air and therefore appears circumscribed. C: MRI, T1-weighted sagittal reconstruction of the left breast post-contrast. An irregular mass (short arrows) with heterogeneous enhancement and central necrosis (long arrow) is imaged protruding from the upper inner quadrant of the left breast. Diffuse skin thickening and edematous changes are also apparent in the subcutaneous tissue. Following neo-adjuvant therapy, residual non-enhancing soft tissue is imaged on MRI (see Fig. 5.29B) at the site of the original tumor; no residual malignancy is evident at the time of the mastectomy (e.g., complete pathological response [cPR] ) and no metastatic disease is identified in two sentinel lymph nodes.

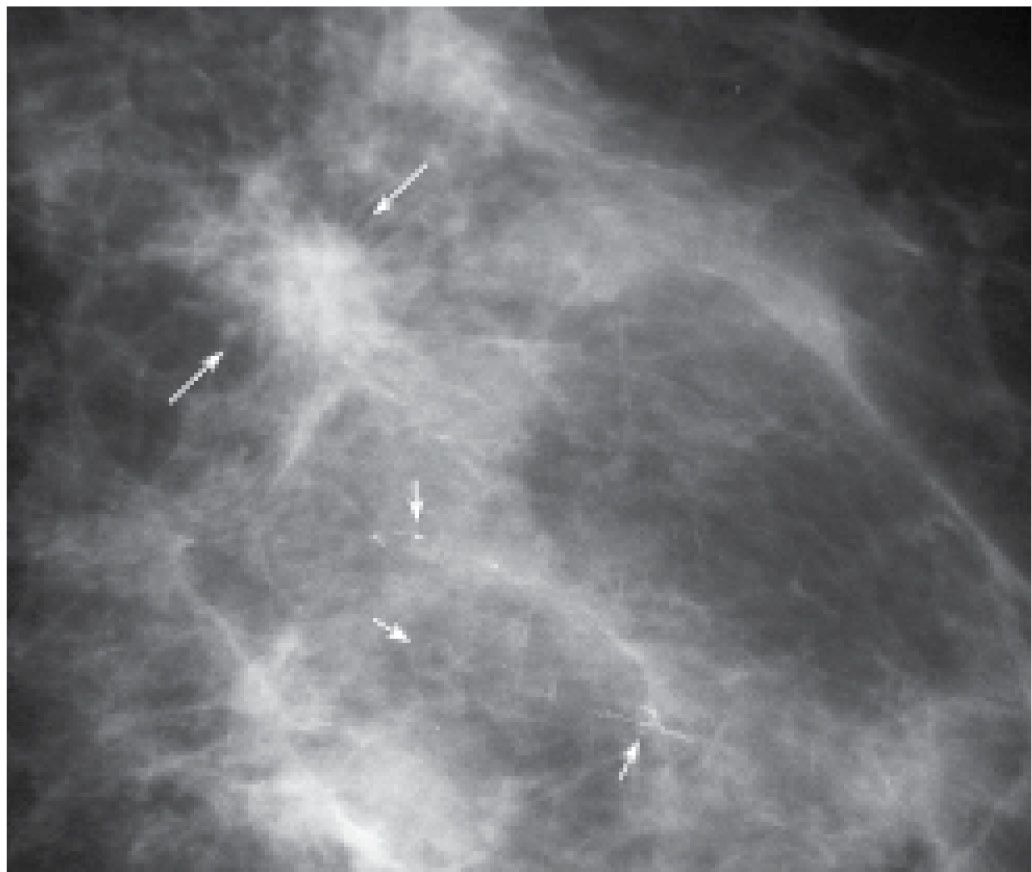

Additional mammographic presentations for invasive ductal carcinoma include focal parenchymal asymmetry (Fig. 8.11), distortion (Fig. 8.12), or diffuse changes (Fig. 8.13; also see Figs. 9.14 through 9.16). All of the presentations may be found in isolation or in combination (e.g., a mass with associated distortion). They may also be associated with malignant-type calcifications that often reflect the presence of intraductal disease. It is important to describe the calcifications particularly when they extend away from the primary finding. If the calcifications are in tissue extending a distance from the mass, a separate biopsy of the calcifications may be appropriate to establish the extent of disease accurately. In planning preoperative wire localizations in these patients, bracketing may be needed to include the area of the calcifications (Fig. 8.14; also see Figs. 7.2B and 7.3).

Breast cancers occur anywhere in the breast but are reportedly more common in the upper outer quadrants. The upper inner quadrants and subareolar area are the next most common sites for the development of breast cancer. Kopans and coworkers (4) have described a predilection for cancer to develop at the periphery of the glandular tissue just deep to the subcutaneous fat or in the glandular tissue interfacing with retroglandular fat. Stacey-Clear et al. (4) reported that in women under the age of 50, more than 70% of cancers develop in this peripheral zone. Since accessory nipples and glandular tissue (see Fig. 9.23) can be found in some women along the milk lines extending bilaterally from the axillae to the groins, breast cancer can rarely develop outside of the breast proper along these milk lines.

In many women, the mammographic features of the mass (e.g., mass with spiculated margins in a patient with no history of trauma or surgery, or a round mass with linear, casting-type calcifications) are such that an ultrasound may not add additional information with respect to the mass. The management for the patient is based on the mammographic findings. In these patients, ultrasound is done to help direct the imaging-guided biopsy and to scan the remainder of the breast, ipsilateral axilla, and the contralateral breast for additional disease. In other patients, however, ultrasound is helpful and compliments mammography in characterizing the primary lesion. For example, in a patient with a mass in whom a cyst is a realistic possibility, the appropriate management for the patient is based on the ultrasound findings (e.g., the BI-RADS for the mammogram alone would be BI-RADS 0: Need additional imaging evaluation). Likewise, as discussed in Chapters 3 and 4, when a patient presents with a palpable finding and dense tissue is seen on spot compression or spot tangential views done at the site of clinical concern, or if there is a possibility that a lesion has been excluded from the field of view, ultrasound is critical in helping characterize the palpable abnormality (Fig. 8.15; also see Figs. 3.1, 3.2, 4.46, and 10.18). On the ultrasound, normal glandular tissue, a cyst, or a solid mass may be imaged corresponding to the palpable finding. The patient’s management will, in large part, depend on the physical findings and ultrasound features of the palpable area. Marked hypoechogenicity, spiculation, microlobulation, vertical orientation, angular margins, a thickened echogenic rim, calcifications, extension of tumor into ducts extending toward the nipple, and branching of tumor away from the nipple with variable amounts of shadowing are findings on ultrasound (see Figs. 4.39 through 4.43) associated with malignant lesions (5). In patients with predominantly fatty tissue, less commonly glandular tissue, the ultrasound study may be normal because the lesion is isoechoic to the surrounding tissue (Fig. 8.15D).

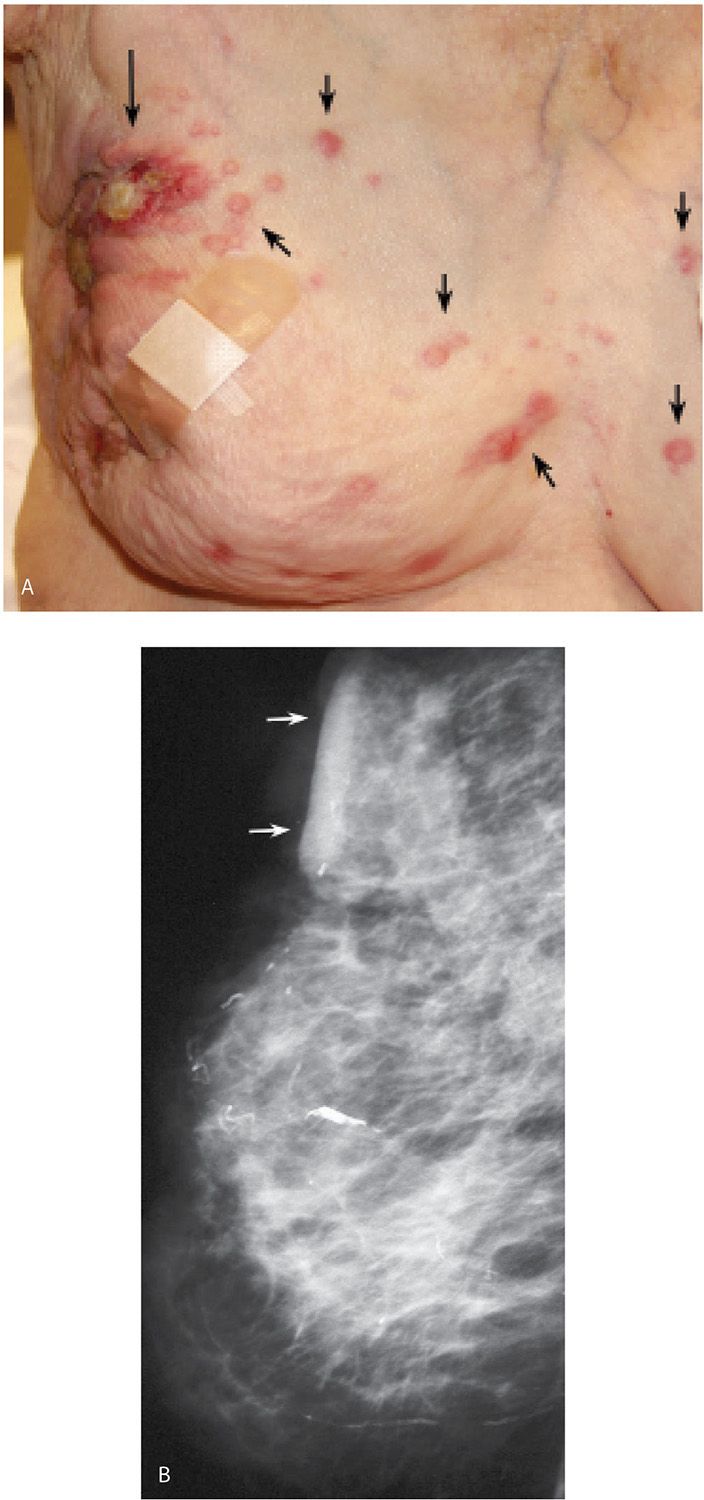

FIG. 8.6 • Skin ulceration, metastatic disease to skin, invasive ductal carcinoma NOS, poorly differentiated. A: Deformed right breast in a 97-year-old patient presenting with locally advanced breast cancer. The right breast is smaller, with skin thickening and several areas of ulceration (long arrow) laterally as well as lateral displacement of the nipple areolar complex. Raised, erythematous nodules (short arrows) on the right breast and medially in the left breast represent skin metastases. B: Right mediolateral oblique (MLO) view demonstrating a diffusely abnormal right breast with decreased compressibility as well as skin and trabecular thickening. Skin thickening is particularly prominent at the site of ulceration (arrows). Some of the mammographic findings may be attributable to ipsilateral axillary adenopathy with resulting lymphatic obstruction. (From Cardeñosa G. Breast Imaging [The Core Curriculum Series]. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.)

FIG. 8.7 • Necrotic breast, invasive ductal carcinoma NOS, locally advanced with metastatic disease to the contralateral axilla. A: The right breast is necrotic and completely replaced by a locally advanced breast cancer in a 50-year-old patient. No nipple areolar complex is evident with necrosis extending into the subclavicular area and the mid-axillary line. Hard masses are palpated in the contralateral (left) axilla. B: CT scan image demonstrating a mass almost completely replacing the right breast with involvement of the skin, as well as the pectoralis and anterior serratus muscles; axillary adenopathy is present bilaterally but because of patient positioning, it is only seen in the left axilla (arrow) on this image.

FIG. 8.8 • Invasive ductal carcinoma NOS, low nuclear grade, and DCIS, cribriform pattern. Spot compression view, right breast CC projection in a 51-year-old patient. Round iso dense mass with spiculated margins. This is a common mammographic presentation for invasive ductal carcinoma. BI-RADS 4C: Suspicious abnormality; biopsy is indicated. When the mass has spiculated margins, it is more commonly a low- to intermediate-grade invasive lesion (e.g., infiltrative pattern). When low-grade invasive lesions have associated DCIS, it is typically low- to intermediate-grade DCIS. In this patient, the tumor is estrogen- and progesterone-positive and HER2/neu-negative. The sentinel lymph node (LN) biopsy (0/3 LNs) is negative.

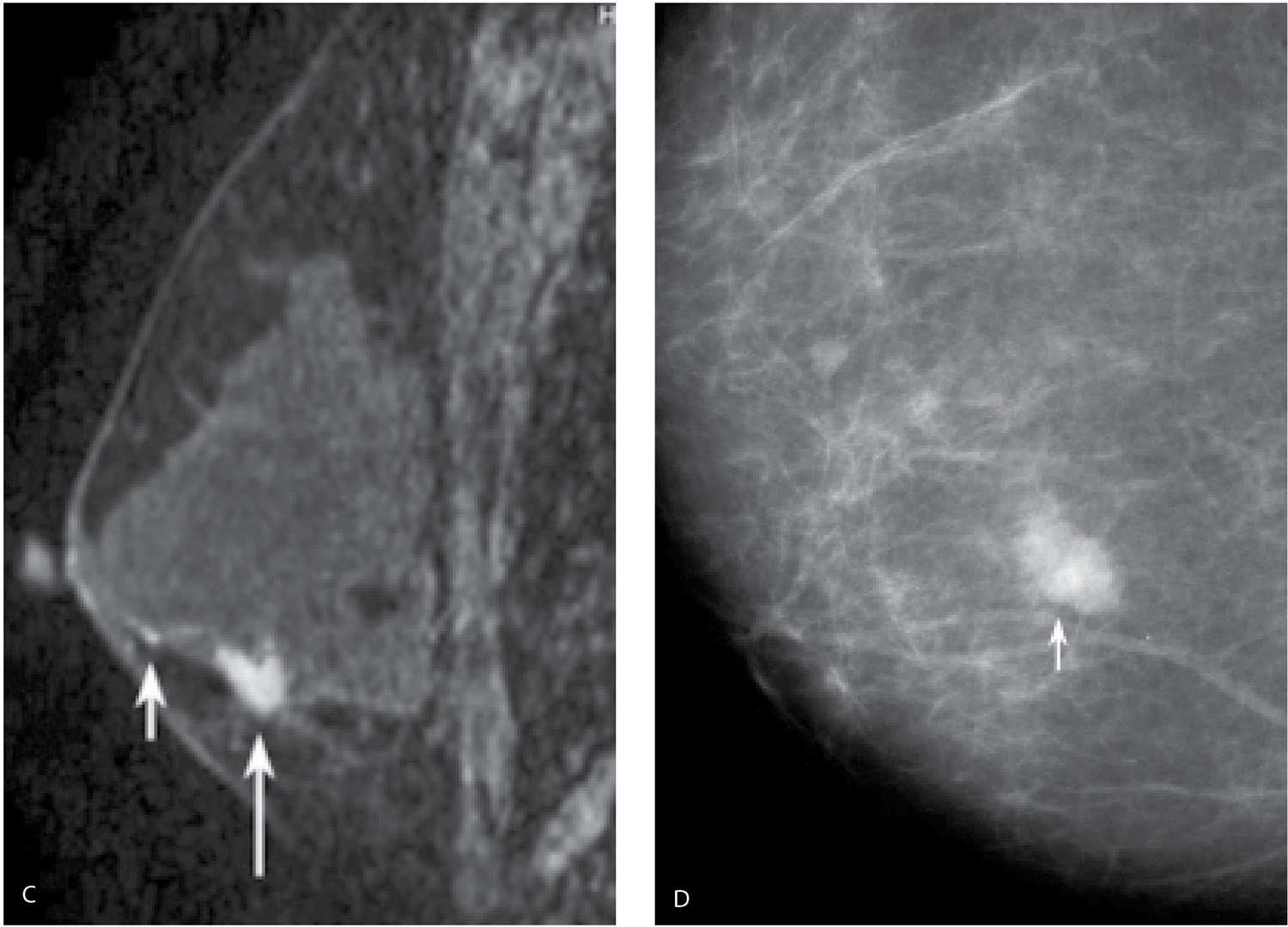

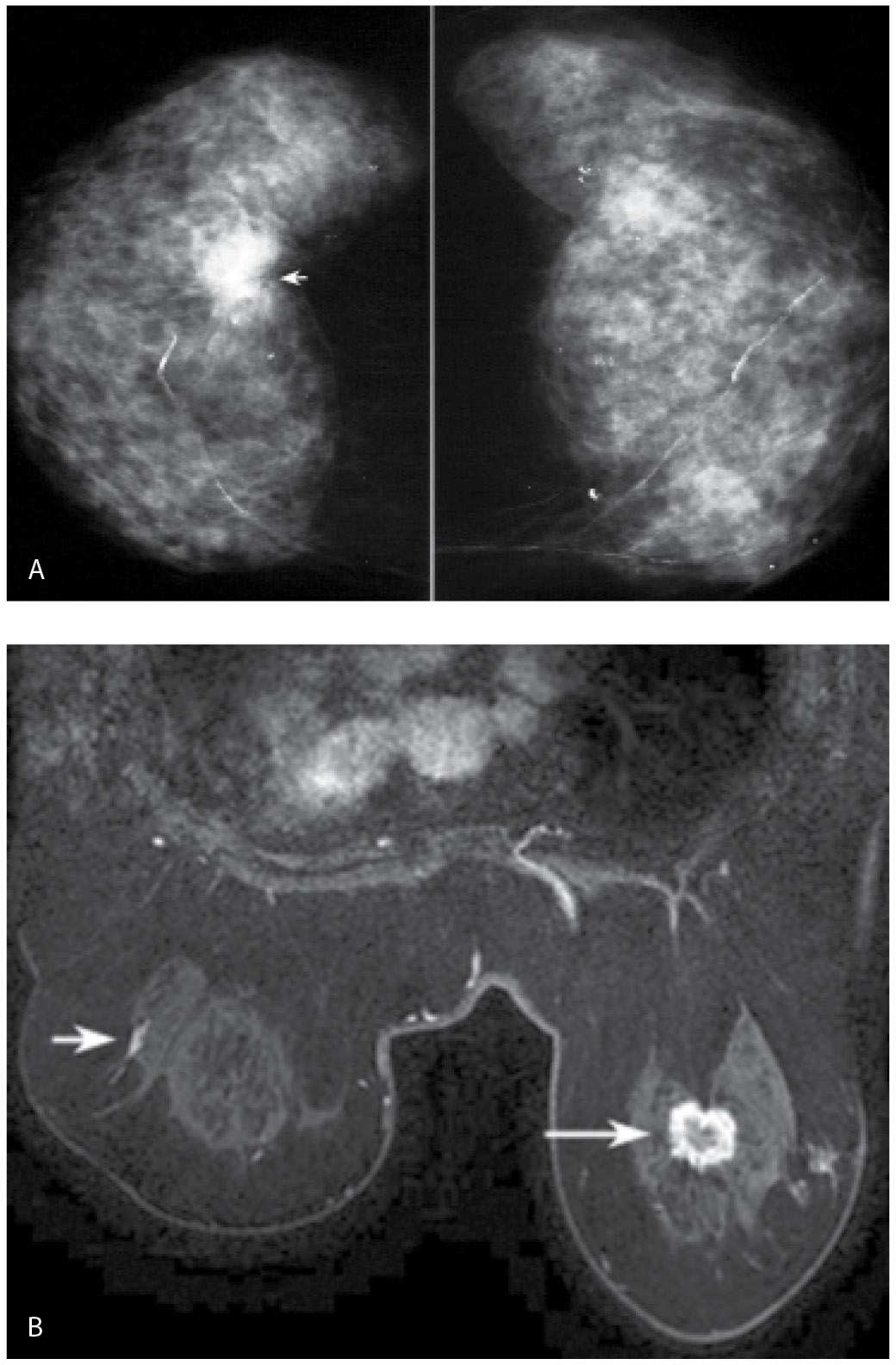

It is important to recognize that patients with breast cancer have a higher risk of concurrent ipsilateral or bilateral breast cancer, or developing subsequent breast cancer. The presence of multiple lesions at the time of diagnosis is something that has been described by pathologists for years and is now also evident when breast MRIs are done routinely in patients with known breast cancer. Multifocal lesions are defined as multiple cancers occurring in the same quadrant (Figs. 8.9C and 8.16). Multicentric cancers are those occurring in different quadrants of the involved breast, or if more than 5 cm apart in the same quadrant (Fig. 8.13; also see Figs. 2.50, 5.21, and 5.22). Bilateral cancers are synchronous when diagnosed at the same time (Fig. 8.17; also see Figs. 2.51 and 5.23) or within 6 months of each other, and metachronous (Fig. 8.18; also see Fig. 2.47 and 10.11) when they occur bilaterally at different times (diagnosed more than 6 months apart). The reported frequency of multifocality varies depending on study design and meticulousness of histological evaluation, and may be as high as 33% to 50% (6,7). The described frequency of synchronous lesions is 0.1% to 2% compared with 1% to 12% for metachronous lesions. In the general population, 0.1% of women per year are expected to develop breast cancer. In comparison, the frequency of developing a second breast cancer among patients with a history of breast cancer is 0.53% to 0.8% per year (7). Nielsen and colleagues (8) reported on 86 women with a diagnosis of invasive ductal carcinoma in whom at autopsy invasive and in situ lesions were identified in the contralateral breast in 33% and 35% of patients, respectively. In a separate study, done by the same investigators on an age-matched population, autopsy results identified 14 patients with in situ lesions and only 1 patient with invasive cancer among 77 women with no history of breast cancer (9).

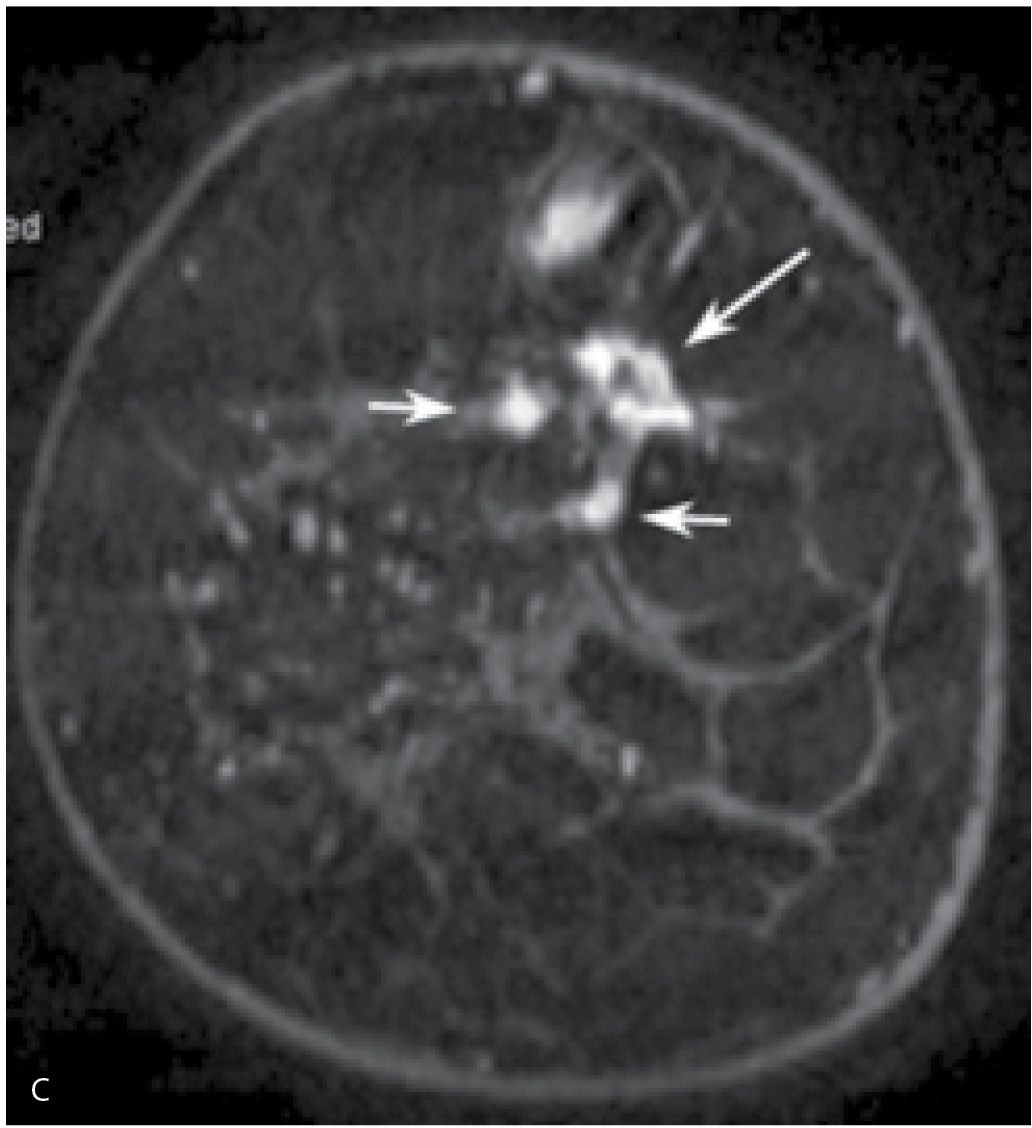

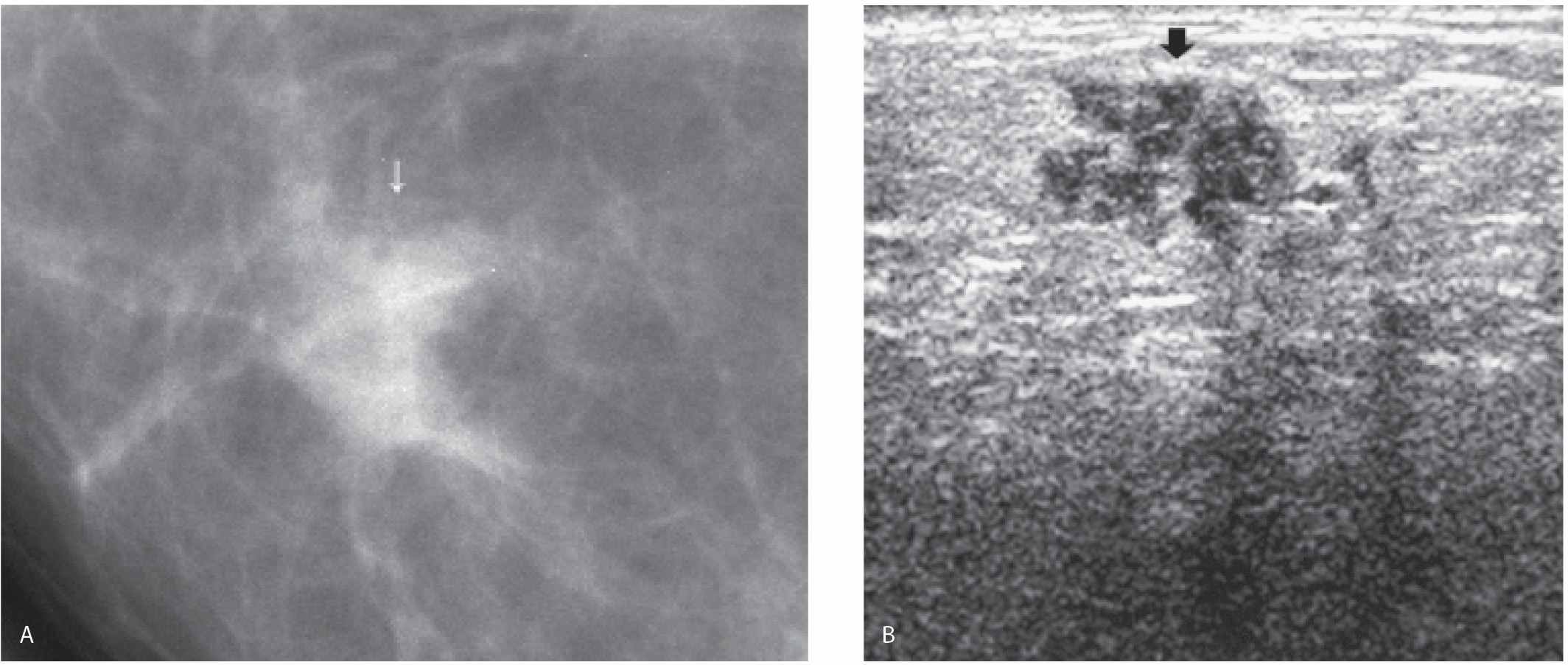

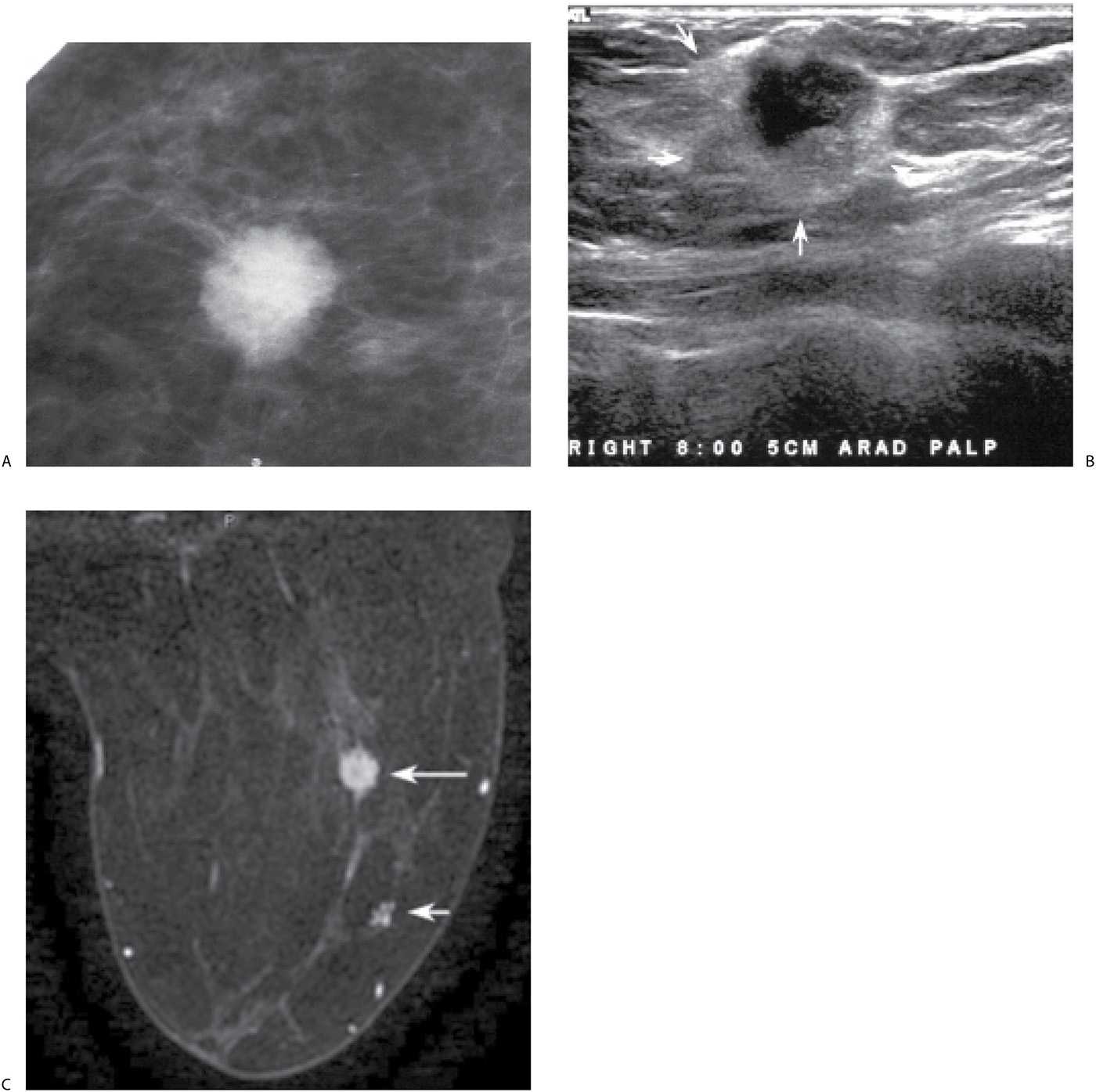

FIG. 8.9 • Invasive ductal carcinoma NOS, intermediate grade with extensive DCIS intermediate nuclear grade (EIC). A: Spot compression view, right breast CC projection in a 65-year-old patient. A dense round mass with microlobulated margins as well as a few punctate calcifications is present. B: Ultrasound. A mass (arrows) with a heterogeneous echotexture is imaged correlating to the mammographically detected mass. Echogenic foci in the mass are thought to represent calcifications. BI-RADS 4C: Suspicious abnormality; biopsy is indicated. Please note that although this patient has a screen-detected abnormality, the lesion is palpable at the time of the focused ultrasound (PALP). When the patient is positioned for the ultrasound and palpation is done as the patient is scanned, many screen-detected cancers can be palpated. An invasive ductal carcinoma, intermediate nuclear grade is diagnosed on core biopsy. It is estrogen and progesterone receptor-positive and HER2/neu-negative. C: MRI, axial T1-weighted image of the right breast post-contrast. A round mass (long arrow) with lobulated margins and heterogeneous enhancement characterized predominantly by rapid wash-in and wash-out kinetic curves is correlated to the mass detected mammographically and the site of the patient’s known invasive ductal carcinoma. Focal, non-mass–like heterogeneous enhancement (short arrow) is detected anterolaterally in the right breast, 2.8 cm anterior to the known site of invasive disease. DCIS, solid and cribriform types, low nuclear grade is diagnosed on an MRI-guided biopsy of this site. The sentinel lymph node biopsy is positive, and as such a full axillary dissection is done (1/16 positive LNs). An extensive intraductal component is described at the time of the patient’s lumpectomy. As illustrated by this patient and discussed in Chapter 5, additional sites of disease (multifocal, multicentric, and bilateral) are detected routinely on MRI’s in patients with a new breast cancer diagnosis.

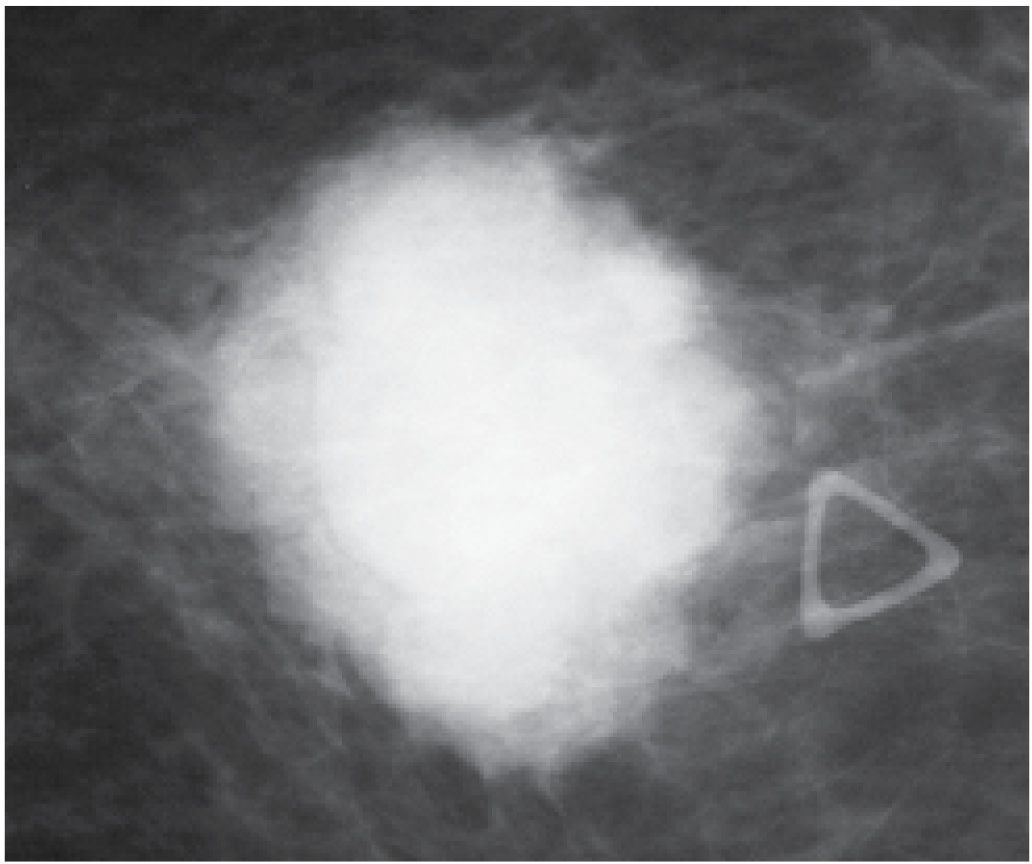

In analyzing masses and considering an appropriate differential for possible malignant etiologies the age of the patient, any physical findings and the imaging features of the lesion are helpful. Many of our patients presenting with a round high-density mass (expansile margins, or “blow up” lesions) on the mammogram, and marked hypoechogenicity, cystic spaces (see Fig. 4.37), and posterior acoustic enhancement on ultrasound, are diagnosed with poorly differentiated, rapidly growing invasive ductal carcinomas, NOS (see Table 7.8 for differential considerations). In the younger patients (pre-menopausal), these lesions may represent interval cancers (cancers presenting between screening studies) and are often triple-negative lesions (estrogen and progesterone receptor-negative, HER2/neu-negative) (Fig. 8.19). The triple-negative cancers are also reportedly more common in African American patients (10,11). On physical examination, these lesions are often seemingly larger than the lesion seen on mammography or ultrasound (Leborgne law). If there is associated intraductal disease, it is usually characterized by central necrosis such that linear calcifications may be seen mammographically. In patients with an “expansile” mass, it is appropriate to consider some of the more common invasive ductal subtypes including medullary, mucinous, papillary, and metaplastic carcinomas. Medullary carcinomas are more common in younger premenopausal patients and may present as interval cancers. Mucinous and papillary carcinomas are slower growing (less likely to be interval cancers) and more common in post-menopausal women. On ultrasound, mucinous carcinoma may be difficult to identify because it is often iso to slightly hyperechoic, and papillary carcinomas are usually a complex cystic mass in the subareolar area. Except for the pleomorphic variant (rare), invasive lobular carcinoma rarely presents as a round mass and as such it is usually not included in the differential for round masses.

FIG. 8.10 • Invasive ductal carcinoma NOS, high nuclear grade. A: Spot compression view, left breast MLO projection in a 65-year-old patient. Oval, high-density mass with indistinct margins is confirmed in the left breast. B: Ultrasound. An oval hypoechoic, horizontally oriented mass (arrow) is imaged in the left breast correlating to the mass identified mammographically. At the time of the ultrasound, this mass could not be palpated. Given the patient’s age and the mammographic features of this lesion, biopsy is done. BI-RADS 4C: Suspicious abnormality; biopsy is indicated. An invasive ductal carcinoma high nuclear grade is reported on the cores. The tumor is estrogen and progesterone receptor-negative, HER2/neu-positive. C: MRI, T1-weighted sagittal reconstruction of the left breast post-contrast. An oval mass with irregular and spiculated margins and heterogeneous enhancement is imaged corresponding to the site of the patient’s known malignancy. No other lesions are identified in either breast. The histology is confirmed at the time of lumpectomy. The sentinel LN biopsy is negative (0/3 LNs).

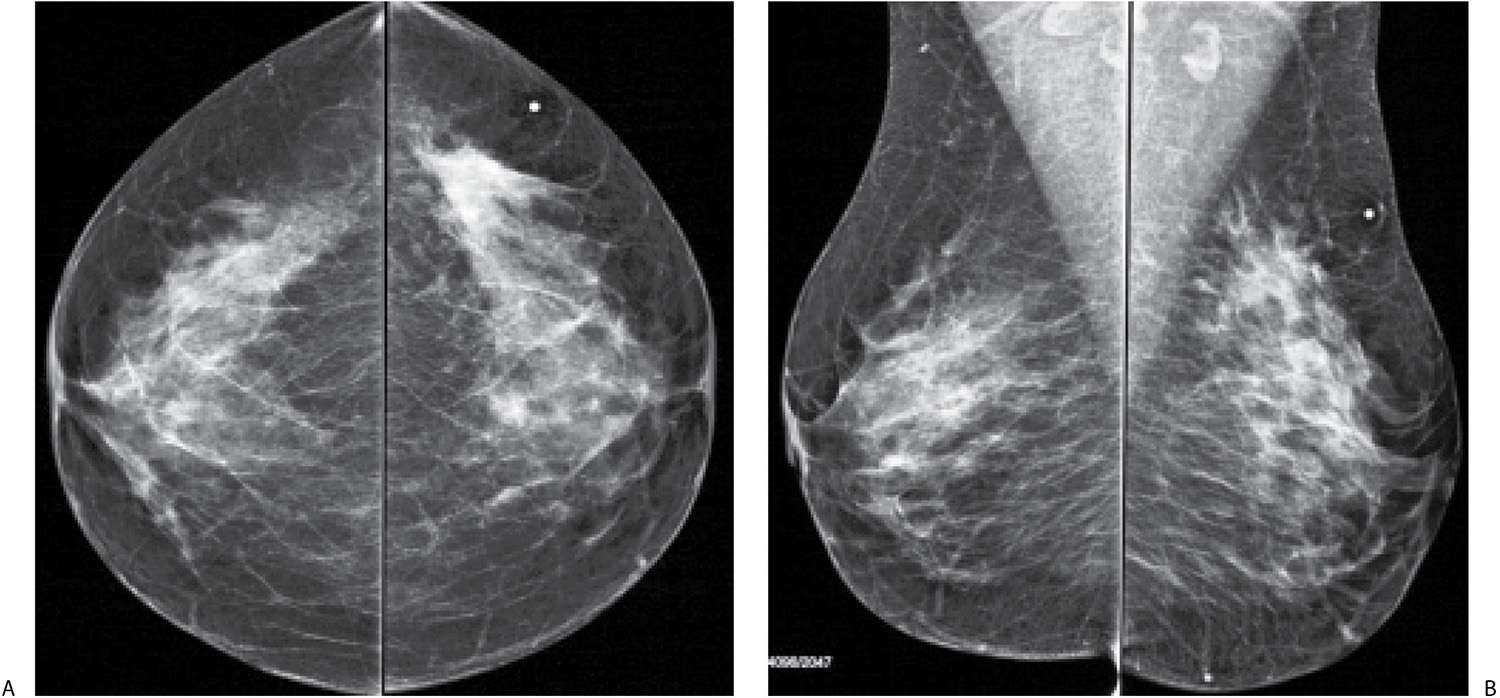

FIG. 8.11 • Palpable asymmetry, invasive ductal carcinoma, NOS intermediate nuclear grade. CC (A) and MLO (B) views in a 47-year-old patient. Parenchymal asymmetry is imaged in the upper outer quadrant of the left breast corresponding to a “lump” (metallic BB) described by the patient; at least on the CC, the area of asymmetry is the densest portion of the mammogram. Note morphologically normal-appearing lymph nodes in the axillae. Palpable parenchymal asymmetry requires evaluation with spot compression view (not shown), correlative physical examination, and ultrasound. The tumor in this patient is estrogen and progesterone receptor-positive, HER2/neu-negative. The sentinel lymph node (LN) biopsy is negative (0/2LNs).

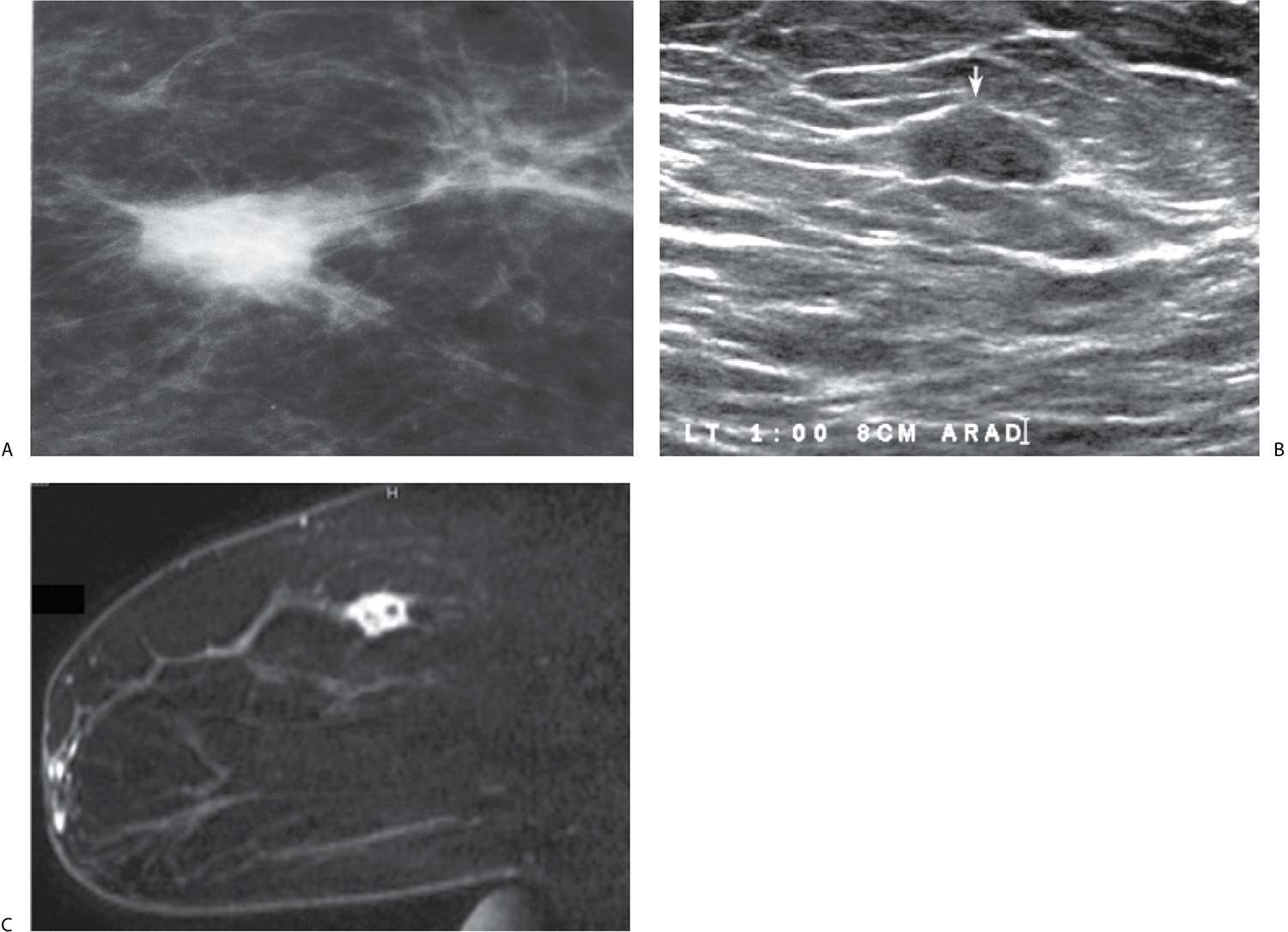

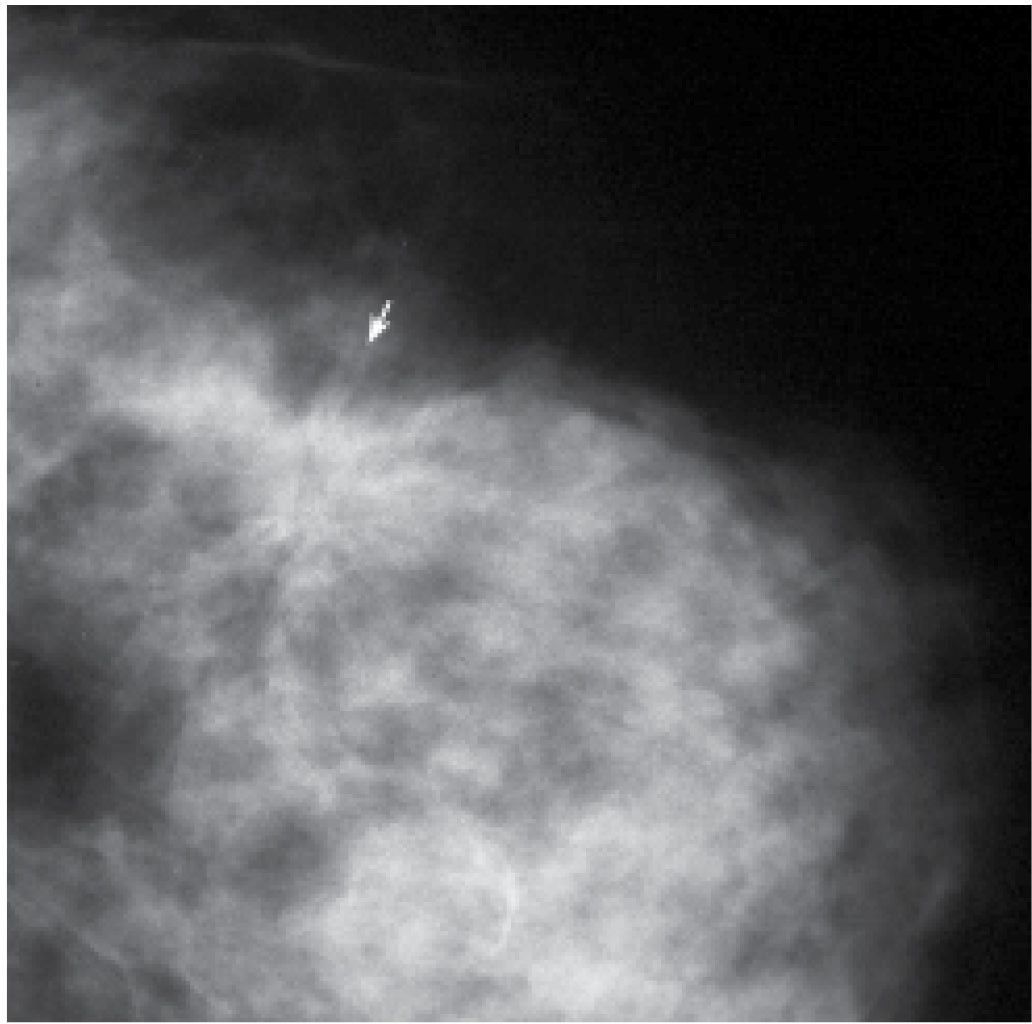

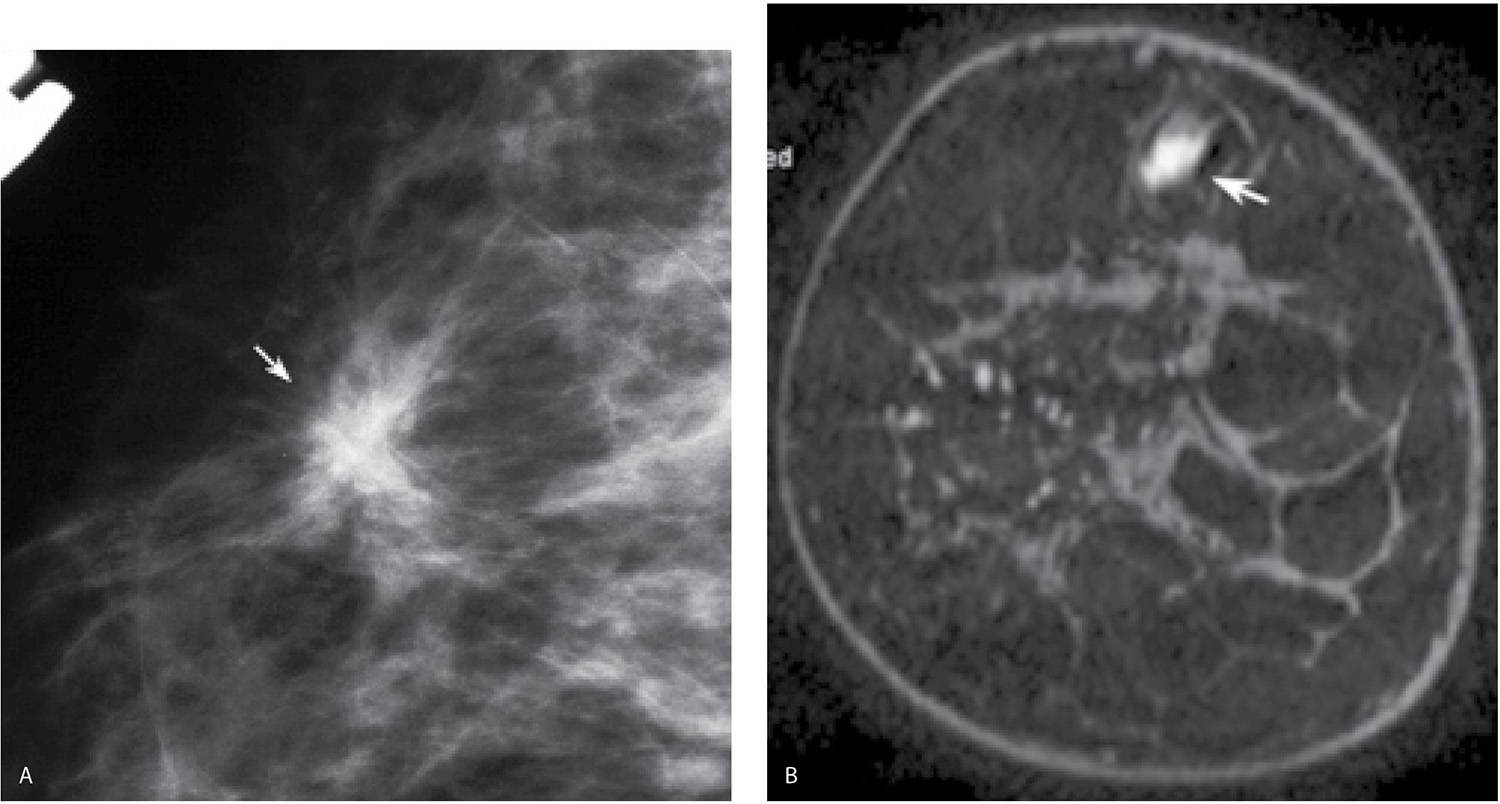

FIG. 8.12 • Invasive ductal carcinoma NOS, intermediate grade. CC view photographically coned to the lateral aspect of the left breast, screening study in a 52-year-old woman. Distortion (arrow) is noted laterally in the left breast. Confirmed on orthogonal spot compression views (not shown). The only thing that might prevent a biopsy with this type of finding (e.g., distortion, spiculation) is a history of prior surgery localized to this site. BI-RADS 4C: Suspicious abnormality; biopsy is indicated. Diagnosis of invasive ductal carcinoma intermediate nuclear grade is established on an ultrasound-guided core biopsy. (From Cardeñosa G. Breast Imaging [The Core Curriculum Series]. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.)

In considering the differential for malignancies presenting with masses that have spiculated margins (see Table 7.9 for differential considerations), invasive ductal carcinoma NOS is the most likely, and many of these are low to intermediate grade. If associated intraductal disease (DCIS) is present, it is not typically characterized by central necrosis; it is often low to intermediate grade such that, if there are calcifications, they are likely to be predominantly fine pleomorphic including round, punctate, and amorphous forms. Of the more common invasive ductal subtypes, tubular carcinoma is the only one that typically presents as one or several small masses with spiculated margins and is more common in pre-menopausal women. Invasive lobular carcinoma is also included in this differential since a mass with spiculated margins is the most common presentation for this type of tumor; patients with invasive lobular are often older post-menopausal women.

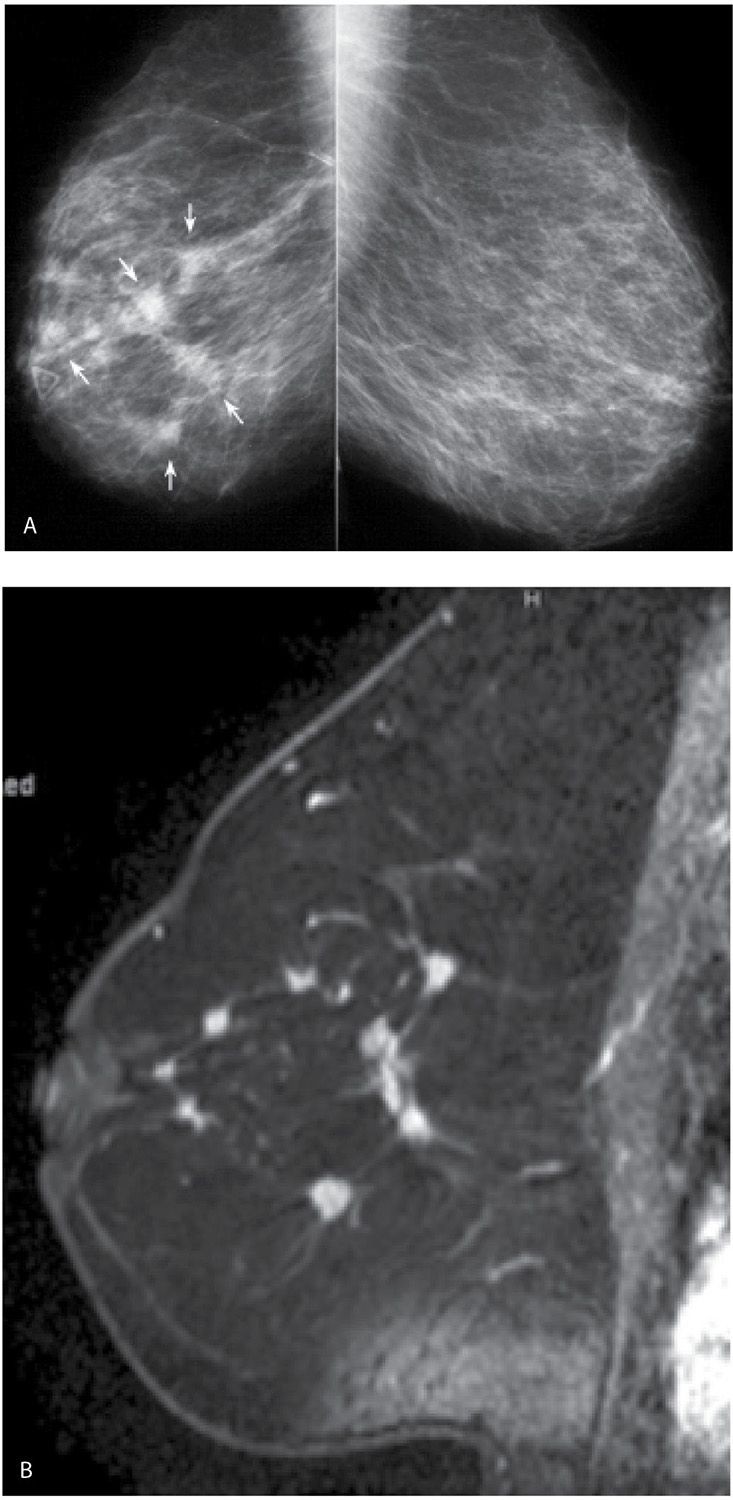

FIG. 8.13 • Multifocal and multicentric invasive ductal carcinoma, NOS intermediate nuclear grade with micropapillary features. A: MLO views in a 72-year-old patient presenting with a “lump” anteriorly (radiopaque triangular marker). As compared to her prior studies (not shown), the right breast is now smaller with diffuse prominence of the trabecular markings and multiple masses (arrows). BI-RADS 4C: Suspicious abnormality; biopsy is indicated. In this patient, the two masses furthest apart are biopsied to establish the extent the disease. B: MRI, T1-weighted sagittal reconstruction of the right breast post-contrast. Multiple masses with spiculated margins and heterogeneous enhancement, are imaged encompassing multiple quadrants in the breast (not all the masses are included at this scan plane). Nipple retraction is also noted on the MRI. The lesions are estrogen and progesterone receptor-positive, HER2/neu-negative. Signal flaring is noted in the area of the inframammary fold.

FIG. 8.14 • Invasive ductal carcinoma, low nuclear grade with associated DCIS. Spot compression view, MLO projection in 63-year-old patient. An iso dense mass (long arrows) with spiculated margins is present. Fine pleomorphic (round and punctate) calcifications (short arrows) are noted extending away from the mass with some of the calcifications demonstrating a linear distribution. BI-RADS 4C: Suspicious abnormality; biopsy is indicated. In taking care of this patient, biopsies are done of the mass and the anterior-most extent of the calcifications, thereby establishing the extent of the disease. If the patient wants conservative therapy, bracketing the mass and calcifications with two wires is important preoperatively. Likewise, alerting the pathologist to the location of the calcifications away from the primary finding on the specimen radiograph is critical in establishing an accurate diagnosis and extent of disease. In this patient, synchronous DCIS is diagnosed on MRI (not shown) in the contralateral breast.

FIG. 8.15 • Invasive ductal carcinoma, NOS. A: MLO views in a 37-year-old patient who presents describing a “lump” in her left breast. The metallic BB marks the site of the palpable finding. Dense tissue is imaged at the site of concern on all images (CC and spot tangential views not shown). B: Ultrasound. An irregular, vertically oriented, markedly hypoechoic mass (arrows) with angular margins and a thickened and irregular echogenic rim is imaged in the lower outer quadrant of the left breast corresponding to a discrete, fixed hard mass (PALP). BI-RADS 4C: Suspicious finding; biopsy is indicated. This BI-RADS is based on the clinical and ultrasound findings, not the mammogram (which in this patient is normal). The evaluation of a patient with dense tissue mammographically corresponding to a site of concern is incomplete without correlative physical examination and an ultrasound. The diagnosis in this patient is established after an ultrasound-guided biopsy. C: MRI, T1-weighted sagittal reconstruction of the left breast post-contrast. A homogeneously enhancing irregular mass (long arrow) with smooth margins is imaged in the lower outer quadrant of the left breast zone B. Clumped and linear enhancement (short arrow) is identified extending anteriorly from the mass for approximately 2 cm consistent with associated DCIS. D: CC view of the right breast photographically coned to medial quadrants in a different patient. An oval dense mass (arrow) with indistinct margins is identified in the right breast. The features of this mass are confirmed on spot compression views (not shown). Seemingly normal tissue is seen on ultrasound at the expected location for this mass. Since no cyst is imaged, it is presumed that the mass seen mammographically is solid and isoechoic with surrounding tissue. Given the mammographic features (new, medial location, margins), a stereotactically guided biopsy is done to establish the diagnosis of invasive ductal carcinoma, poorly differentiated. BI-RADS 4C: Suspicious finding; biopsy is indicated.

FIG. 8.16 • Multifocal, invasive ductal carcinoma NOS, intermediate grade. A: Spot compression view, right breast MLO projection done to further evaluate possible distortion noted on the screening mammogram in a 76-year-old woman. A dense irregular mass (arrow) with spiculated margins and associated distortion is confirmed on orthogonal spot compression views (only one projection is shown). BI-RADS 4C: Suspicious abnormality; biopsy is indicated. Ultrasound-guided biopsy (not shown) is done to establish the suspected diagnosis. B: MRI, T1-weighted coronal reconstruction, right breast pre-contrast. An oval mass with high T1 signal (arrow) is seen superiorly in the right breast prior to the contrast bolus consistent with a biopsy-related hematoma. C: MRI, T1-weighted coronal reconstruction, right breast post-contrast. Three enhancing masses are identified on the MRI. The largest of these (long arrow) demonstrates spiculated margins and heterogeneous enhancement and corresponds to the mass identified mammographically and the site of the patient’s known invasive ductal carcinoma. Two smaller (“satellites”) more homogeneously enhancing masses (short arrows) are seen in close proximity to the primary lesion. Three foci of invasive ductal carcinoma are confirmed at the time of the patient’s lumpectomy. In comparison with the pre-contrast image shown in part B, the hematoma shows no enhancement.

In patients with known invasive breast primaries, we routinely scan the ipsilateral axilla (see discussion at the end of this chapter). Ultrasound evaluation of the ipsilateral axilla in patients with a probable malignancy can be useful because it provides access to an area that may be difficult to evaluate on the mammogram. If a suspicious lymph node is identified, a core biopsy or fine needle aspiration is done at the time of biopsy of the primary breast lesion. Patients identified with metastatic disease bypass sentinel lymph node biopsy and go on to have full axillary dissections at the time of the lumpectomy. Alternatively, depending on the size of the primary, patients with positive axillary lymph nodes at the time of presentation may be treated with neo-adjuvant therapy prior to any surgery.

Histologically, invasive ductal carcinomas NOS demonstrate variable growth patterns (infiltrative, expansile), cellular morphology, and no special features. Several grading systems are available based on tubule formation, nuclear morphology, and mitotic activity. Estrogen receptors are reportedly positive in 55% to 72% of lesions; however, poorly differentiated lesions are less likely to have estrogen receptors. Progesterone receptors occur in 33% to 70% of lesions, and approximately 15% of lesions are estrogen receptor-positive and progesterone receptor-negative (1,2,7). HER2/neu (ERBB2) is an epidermal growth factor receptor (type 2) that may be present in some breast cancers. The ERBB2 gene is amplified in approximately 25% of all breast cancers as well as some ovarian cancers and amplification is almost always associated with overexpression. The amplification of this gene in breast cancers is associated with a bad prognosis such that patients have an increased rate of metastasis as well as decreases in time to recurrence and overall survival. Trastuzumab (Herceptin) is used in the treatment of patients with HER2/neu-positive tumors (1).

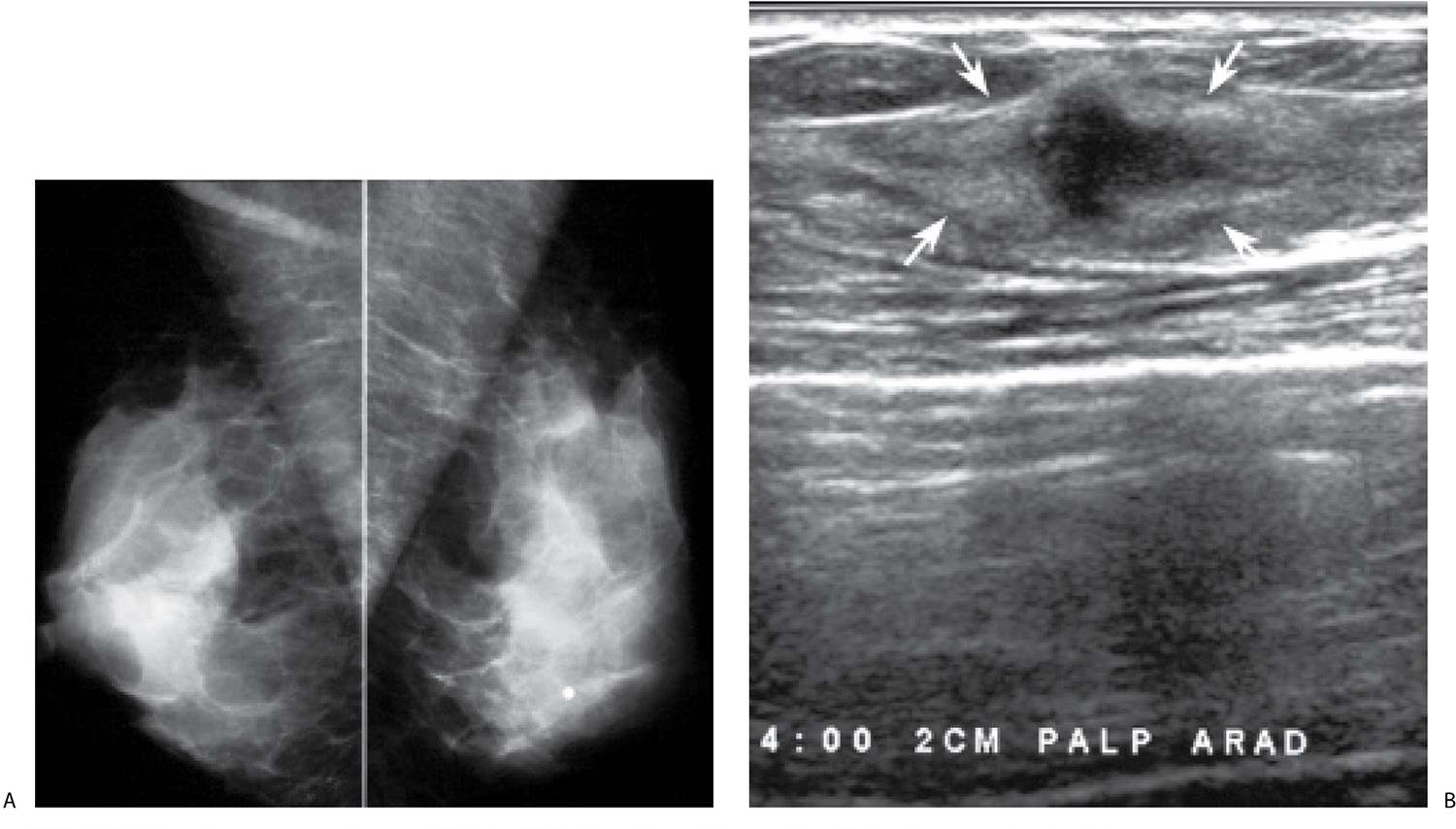

FIG. 8.17 • Synchronous lesions, invasive ductal carcinoma NOS intermediate grade in the right breast and DCIS (extensive), intermediate grade in the left breast. A: CC views in a 72-year-old woman. Dense breast parenchyma is present with arterial calcification and dystrophic-type calcifications scattered bilaterally (left more than right). A dense, round mass with indistinct and spiculated margins is present at the glandular tissue–retroglandular fat interface in the right breast. Note also that this is the densest area in this patient’s mammogram. A hypoechoic mass with internal echoes consistent with calcifications, indistinct, spiculated and angular margins, and shadowing is imaged on ultrasound (not shown) corresponding to the mass seen mammographically in the right breast. Although this is a screen-detected abnormality, a hard immobile mass is palpated at the time of the ultrasound. B: MRI, axial T1-weighted image post-contrast. A mass (long arrow) with thickened, irregular rim enhancement and spiculated margins is imaged in the right breast at the site of patient’s known cancer. Focal non-mass–like linear enhancement (short arrow) is noted in the left breast laterally in zone B. DCIS intermediate grade is diagnosed on an MRI-guided biopsy. The findings are confirmed at the time of bilateral lumpectomies. The DCIS in the left breast is described as extensive; however, no invasion is identified.

EXTENSIVE INTRADUCTAL COMPONENT

Patients with invasive ductal carcinomas and extensive areas of associated intraductal carcinoma were initially thought to have a worse prognosis, and were described as having a higher incidence of local recurrence following conservative treatment. This is probably related to incomplete resection of the lesion and residual disease in the breast (12). When patients with lesions having EIC are adequately resected, prognosis is not significantly different from that of women with lesions lacking EIC (13,14). When malignant-type calcifications, or clumped and linear enhancement on MRI, are seen extending for a distance away from a clinically or mammographically detected mass (Fig. 8.14; also see Figs. 7.2B, 7.3, and 3.16), it is important to alert the surgeon and pathologist with respect to the extent of disease and adequately bracket the area at the time of surgery so that the intraductal disease is resected with the invasive component. MRI is the best modality available in detecting and characterizing the extent of EIC (e.g., DCIS is underdiagnosed and the extent underestimated on mammography). Definitions of EIC have varied. Currently, EIC is diagnosed when DCIS constitutes 25% or more of the invasive tumor, or when DCIS is present within and extends beyond (Fig. 8.9C and 8.14) the invasive component (1,2,7,15).

FIG. 8.18 • Metachronous lesions, invasive ductal carcinoma, NOS. A: MLO view, left breast photographically coned to the upper portion of the image. An irregular iso dense mass (arrow) with indistinct margins is detected on the screening study. Invasive ductal carcinoma is diagnosed following imaging-guided biopsy. B: MLO view, right breast, 3 years following “A” photographically coned to the upper portion of the image. A developing density (arrow) with possible calcifications is seen superiorly in the right breast. BI-RADS 0: Need additional imaging evaluation. C: Double spot compression magnification views (only MLO projection is shown) confirm the presence of an irregular iso dense mass with associated calcifications. In patients with a history of breast cancer, aggressively pursue any perceived changes in the contralateral breast. In this patient, the second lesion is arising in tissue, is irregular, and has associated DCIS consistent with a second primary rather than metastatic disease from the contralateral breast (metastatic disease often presents as one or several round or oval masses, and typically does not have associated DCIS). (From Cardeñosa G. Breast Imaging [The Core Curriculum Series]. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.)

FIG. 8.19 • Invasive ductal carcinoma NOS, high nuclear grade. Dense, round, mass with microlobulated, indistinct margins corresponding to a “lump” described by the patient in her left breast (triangular opacity used to denote the palpable finding). This is a rapidly developing expansile (“blow up”) lesion in a 48-year-old pre-menopausal woman. Not surprisingly, it is a triple-negative (estrogen and progesterone receptor, HER2/neu-negative), poorly differentiated invasive ductal carcinoma.

DUCTAL CARCINOMA IN SITU

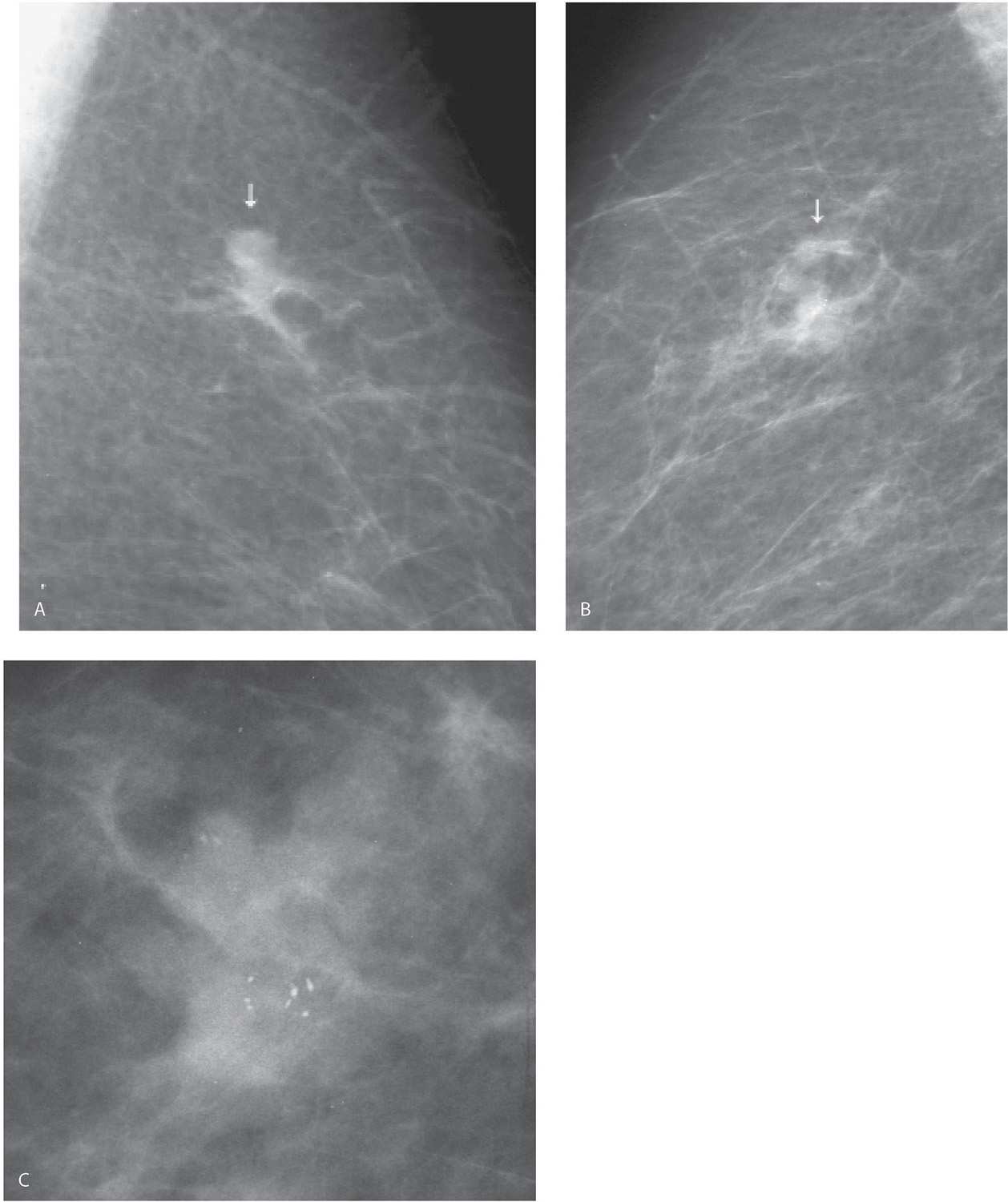

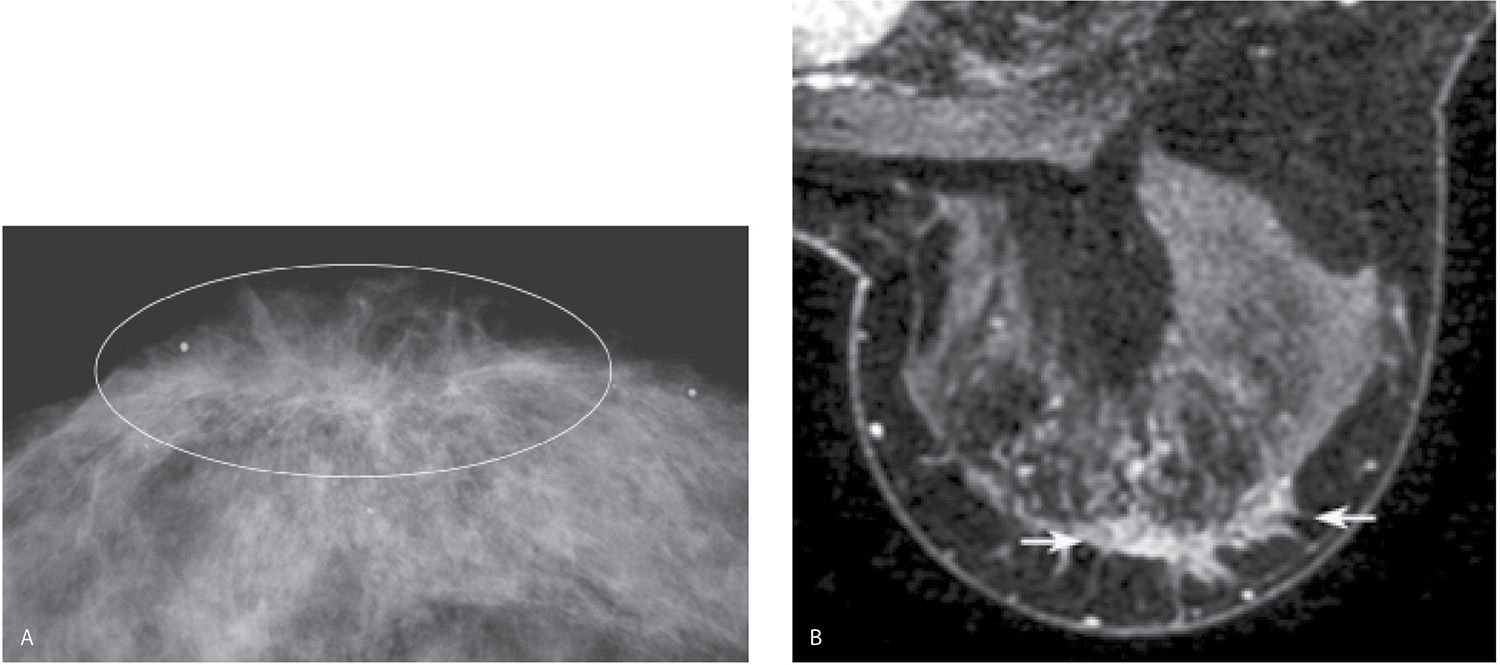

As discussed in Chapter 6, DCIS is now most commonly diagnosed in asymptomatic women following the detection of calcifications on screening mammograms or the identification of clumped and linear enhancement following MRI. Prior to the widespread use of screening mammography, however, DCIS was uncommon and constituted less than 5% of all breast cancers; patients presented with a palpable mass, spontaneous nipple discharge, or Paget disease of the nipple (16). Although uncommon (so much so that DCIS is rarely included in the differential of an uncalcified, mammographically detected mass), DCIS can be detected as an uncalcified, round, oval, irregular or microlobulated, mass with partially circumscribed (Fig. 8.20) or spiculated margins (Fig. 8.21), distortion (Fig. 8.22), developing ductal distension (see Figs. 5.38, 9.35, and 9.36), parenchymal asymmetry (see Figs. 9.27 and 9.28), or diffuse change (see Figs. 9.20 and 9.21 and Table 6.6 for DCIS presentations). These findings are attributable to the presence of distended, cancer-containing ducts, in aggregate, and an associated periductal inflammatory process. Histologically, central necrosis may be present.

FIG. 8.20 • Multifocal, DCIS high nuclear grade. A: Spot compression view, in a 73-year-old patient called back from screening for a mass in the right breast. The spot compression views (only one is shown) demonstrate an irregular low-density lobulated mass (arrow) with circumscribed and indistinct margins in the medial aspect of the right breast. B: An irregular mass (arrow) with heterogeneous echotexture and angular margins is imaged in the upper inner quadrant of the right breast corresponding to the area of mammographic concern. BI-RADS 4C: Suspicious abnormality; biopsy is indicated. Ultrasound-guided core biopsy is done. Diagnosis of DCIS with no associated invasive disease is confirmed on excisional biopsy. Rarely, DCIS presents with a mass and no associated calcifications. (From Cardeñosa G. Breast Imaging [The Core Curriculum Series]. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.)

TUBULAR CARCINOMA

Tubular carcinomas are uncommon lesions representing less than 2% of all breast cancers and commonly diagnosed in women in their late 40s. These are a subtype of invasive ductal carcinoma with well-differentiated features. The pure form of tubular carcinoma is almost always ER/PR-positive, HER2/neu-negative, and associated with an excellent prognosis, and yet approximately 10% of patients are found to have axillary metastasis at the time of diagnosis (1).

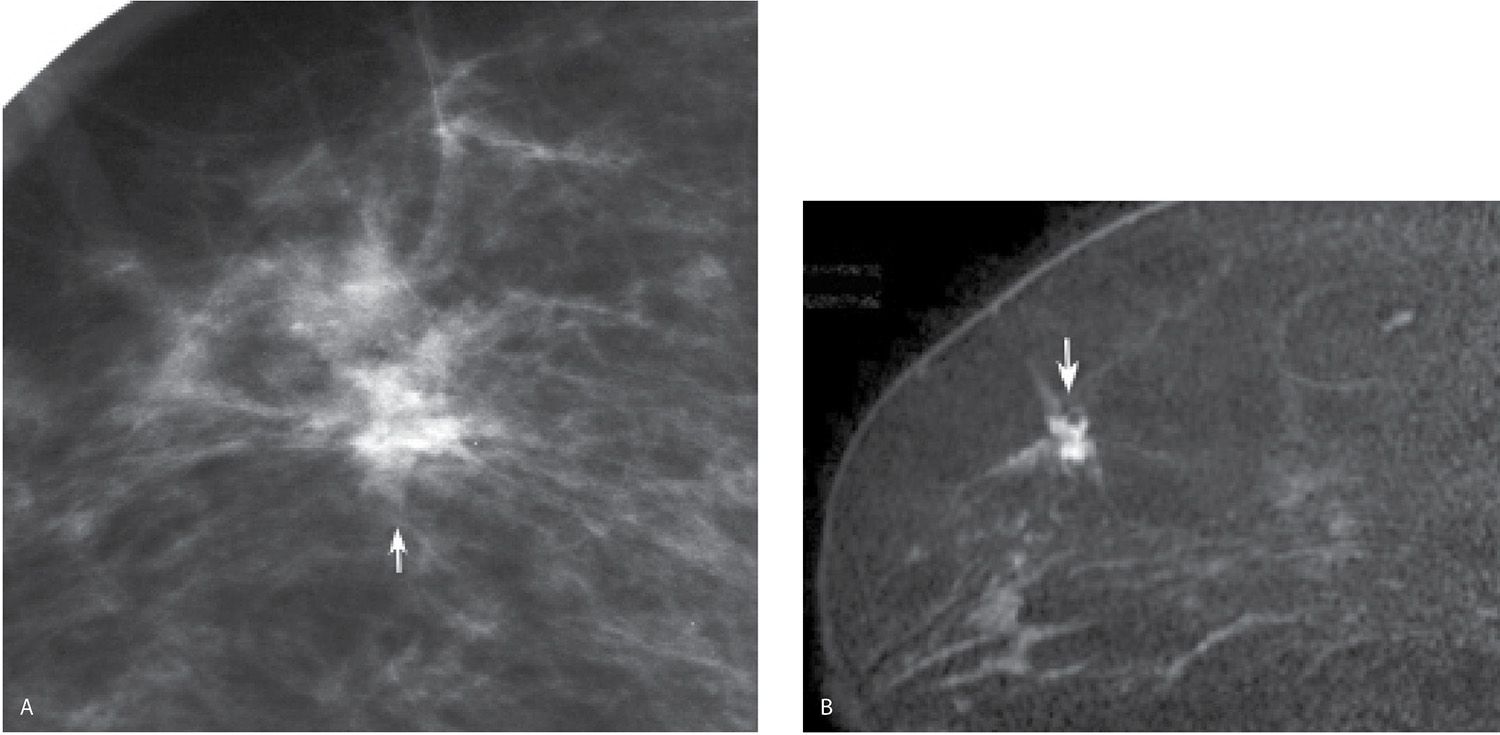

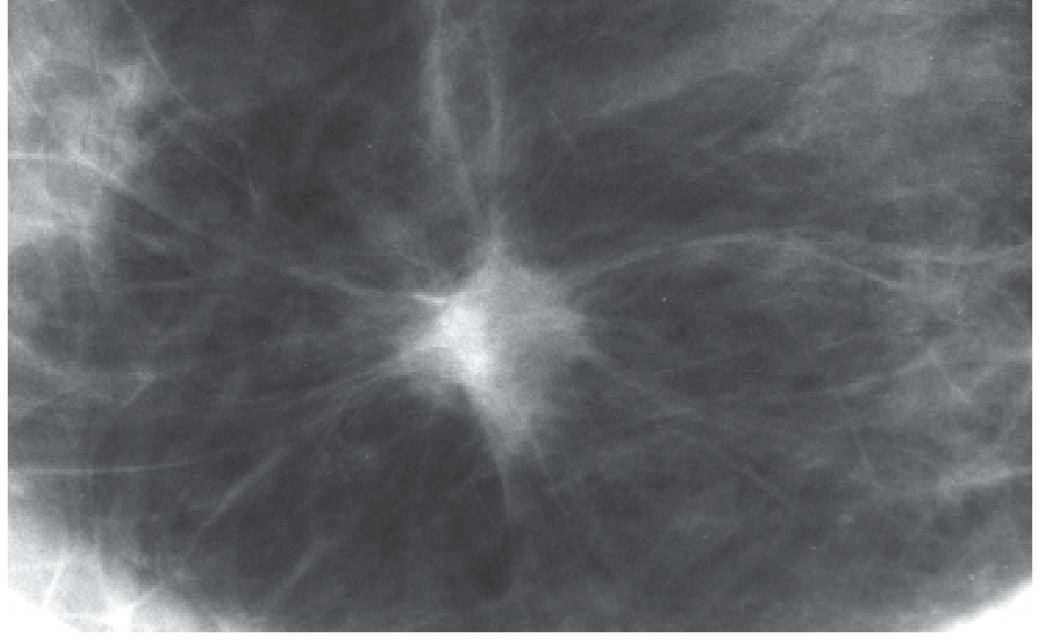

Mammographically, tubular carcinomas are commonly diagnosed as one or more small (<1 cm), iso- to low-density masses with spiculated margins (Fig. 8.23) or distortion in asymptomatic women (17–22). Rarely, these lesions are palpable and may be mammographically occult. Associated fine pleomorphic calcifications including amorphous, round, and punctate forms (Fig. 8.24) may be present since low nuclear grade DCIS lacking central necrosis is reported in as many as 65% of patients with tubular carcinomas. An irregular hypoechoic mass with spiculated, angular margins and shadowing is the most common presentation for tubular carcinomas on ultrasound. Rarely, these tumors may be more round in appearance (Fig. 8.25). On MRI, tubular carcinomas can demonstrate rapid wash-in and wash-out kinetics; however, rarely these lesions may demonstrate little if any enhancement (e.g., false-negative MRI). As with mammography and ultrasound, tubular carcinomas are typically small irregular masses with spiculated margins having heterogeneous less commonly homogenous enhancement; rarely, they may be more round and oval with circumscribed margins (Fig. 8.25A).

FIG. 8.21 • DCIS, high nuclear grade with central necrosis. A: Spot compression view, right MLO projection in a 63-year-old patient confirms the presence of an irregular iso dense mass (arrow) with spiculated margins and associated distortion. Screen-detected abnormality. BI-RADS 4C: Suspicious abnormality; biopsy is indicated. Because no abnormality is identified on ultrasound at the expected location for this finding, a stereotactically guided biopsy is done. “Scant breast parenchyma with fibrocystic changes” is reported on the cores. What do you think? These results are not congruent with the imaging findings. B: MRI, sagittal maximum intensity projection of the right breast. An irregular mass (short arrow) with spiculated margins, heterogeneous enhancement, and associated distortion is imaged corresponding to the mammographic finding. DCIS, high nuclear grade is diagnosed on an MRI-guided core biopsy (see Fig. 12.37G for biopsy image). Morphologically normal-appearing lymph nodes are noted in the right axilla (long arrows). The diagnosis of DCIS with no associated invasive disease is confirmed on excision. Although this patient was diagnosed accurately following the MRI biopsy, it is important to emphasize that, if the MRI had been normal at the site of the mammographic finding, a repeat stereotactically guided biopsy or an excisional biopsy would be indicated for the mammographic finding.

FIG. 8.22 • Distortion, extensive DCIS, intermediate nuclear grade, cribriform and solid patterns. A: CC view right breast photographically coned to the anterior aspect of the breast. Distortion (within oval) of the tissue is identified involving the subareolar area of the right breast. B:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree