This article reviews the most frequent extra-axial tumors of the central nervous system, from the most common meningioma to some uncommon conditions, like Rosai-Dorfman disease, focusing on imaging techniques, pearls, and pitfalls as well as a more practical approach.

Key points

- •

Meningiomas are the most common extra-axial tumor. They have a typical radiologic appearance 75% of the time, including well-demarcated, homogeneous enhancement in extra-axial supratentorial mass, with peritumoral vasogenic edema, hyperostosis, and a dural tail.

- •

Hemangiopericytomas (HPCs) are extra-axial mesenchymal tumors, characterized by high vascularization and cellularity. Radiologically they often appear as lobulated noncalcified masses with heterogeneous MR imaging signal, internal signal voids, and associated bone erosion. Several granulomatous diseases, such as sarcoidosis, Langerhans cells histiocytosis, and Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD), can present as extra-axial masses and may mimic meningioma.

- •

In adults, masses localized in the sellar region are mainly pituitary adenomas and craniopharyngiomas — the squamous and papillary subtype, besides other lesions, such as meningiomas or granulomatous diseases, may also be suprasellar.

- •

Epidermoids, dermoids, colloid, arachnoid, Rathke cleft, and craniopharyngiomas are all epithelial-lined cystic masses that can present as extra-axial lesions in adults. Location and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR)/diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) features help in the differential diagnosis.

- •

A practical approach for pineal masses is differentiating germ cell tumors (GCTs) (germinoma and teratoma) from pineal parenchymal tumors. Germinoma is by far the most common pineal tumor, showing typically homogenous attenuation and enhancement and central calcification.

Meningioma

Meningiomas are nonglial and extra-axial dural-based tumors. They are the most common nonglial primary brain and central nervous system (CNS) tumor, accounting for 35% of all histologic reports. The autopsy prevalence is estimated at 1% to 1.5%, and meningiomas are frequent incidentalomas in 1% to 3% of adults screened as volunteers for MR imaging research or during executive physicals that include neuroimaging.

Meningiomas arise from arachnoid meningothelial (cap) cells, especially where arachnoid granulations are numerous (along the dural sinuses).

Classic or typical meningiomas, which account for more than 90% of all meningiomas, including several subtypes (transitional, fibroblastic, and meningothelial), are World Health Organization (WHO) grade 1 neoplasms. Less than 1 in 10 (8.3%) of all meningiomas are atypical meningioma, which are WHO grade 2. Less than 1% are classified as malignant or anaplastic meningioma, WHO grade 3. The subtype of papillary meningioma is also included in WHO grade 3.

Inherited susceptibility to meningioma is suggested by multiplicity, family history (NF2), and sporadic mutations in tumor suppressor genes (chromosome 22q). Atypical and malignant meningiomas incur additional genetic alterations; malignant meningioma typically has reactivation of telomerase or inactivation of CDKN2A.

Ionizing radiation exposure is an established risk factor, and meningiomas are the most common radiation-induced tumors, with a latency of 20 to 35 years after initial radiotherapy.

Because women are twice as likely as men to develop meningiomas, these tumors show a correlation with breast cancer, and they may increase size and/or present during pregnancy. They harbor hormone receptors (progesterone receptors in 66%–88% and estrogen receptors are less common). An etiologic role for female sex hormones (both endogenous and exogenous) has been hypothesized.

Obesity has newly been related to enhanced risk for meningioma.

Head trauma and cell phone use have also been suggested as a risk factor for meningioma, although the results across studies are not consistent in proving these controversial associations.

Approximately 90% of all meningiomas are located above the tentorium. The most common locations include the cerebral convexity, parasagittal/falx, the sphenoid ridge, the olfactory groove, or parasellar-like tuberculum sella. The cerebellopontine angle is the most common place for infratentorial meningiomas, accounting for 8% to 10% of them, and the paranasal sinuses are the most common extracranial location. Meningiomas also represent approximately 25% of all intraspinal tumors.

Data from the Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States demonstrate more than 2-fold higher incidence among women. Age-specific incidence rates reveal increasing risk with age in both men and women (typically arising after age 40). Malignant meningioma occurs 10 years earlier than typical meningiomas. Regarding ethnicity, meningiomas are more common in African Americans.

Meningiomas are usually slow growing and indolent (90%). Small tumors near eloquent cortex may present when small (<3 cm) whereas larger tumors are seen in other locations, such as subfrontal/olfactory groove. Symptoms are dependent on location, and include: seizures, headache, paresis, change in mental status, and sometimes focal neurologic deficits.

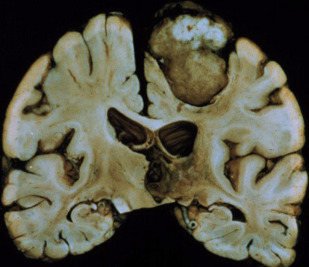

There are 2 basic morphologies for meningiomas: globose (well-demarcated spherical/hemispherical mass with a wide dural attachment and convex toward the brain) and en plaque — a carpet-like thickening of the dura, without parenchymal invagination. On gross inspection, the tumors are usually homogenous and often reddish-brown in color ( Fig. 1 ).

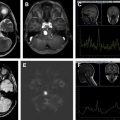

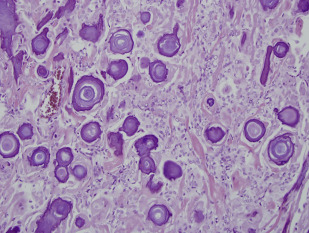

There is a wide range of histologic subtypes. Meningothelial is the most common, characterized by uniform tumor cells, collagenous septa, and psammomatous calcifications ( Fig. 2 ). Other common subtypes include fibrous, transitional, lipoblastic, and microcystic (also called humid).

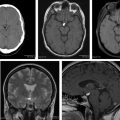

Typical diagnostic features are seen on imaging in 75% of all meningiomas ( Box 1 ), including a sharply circumscribed and homogenous extra-axial mass with a broad-based dural attachment ( Fig. 3 ). Calcification is occasionally seen in approximately 25%. Necrosis, cysts, and hemorrhage are less frequently present. Most meningiomas have a clearly demonstrable cleavage plane that separates them from underlying brain and facilitates surgery. On MR imaging, especially, trapped cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or vessels are often seen in a cleft between the mass and the brain.

Imaging tips

Best modality: MR imaging with contrast. CT: look for typical bone hyperostosis and calcium within the lesion. MRS: might be useful in uncertain cases (ALA peak for well-differentiated and lower ADC with increased cellularity).

Differential diagnosis

HPC: bone destruction, not calcified, lobulated, and narrow dural based

Dural metastasis: skull first affected, multifocal

Granulomatous diseases: multifocal

Pearls, pitfalls, and variants

Atypical meningioma: invasion of brain (shallow/microscopic)

Anaplastic meningioma: intratumoral cystic change, prominent tumor pannus extending away from mass (mushrooming), extracranial extension through foramina

Atypical imaging features do not correspond to atypical histology.

What the referring physician needs to know

Vascular supply: plan need of presurgical embolization

Bone/dural extension and relation between meningioma and brain parenchyma (CSF cleft? Apparent infiltration?): plan surgical strategy to achieve a complete tumoral resection (including bone and dura affected).

On noncontrast CT, typical meningioma is isodense (25%) or hyperdense (75%) to gray matter. Most (>90%) show intense, homogeneous enhancement on postcontrast CT imaging, with a dural tail (on both CT and MR imaging). The dural tail is not a specific feature but is typical of meningiomas and it usually represents reactive vascular changes and dural edema ( Fig. 4 A ).

Intraosseous extension may be evidenced by irregular cortical margins in the skull, hyperostosis, and increased bone vascularity ( Fig. 5 ). Hyperostosis is present in 25% to 60% (or more) of meningiomas and may occur with or without microscopic invasion of the bone.

On MR imaging, meningioma is typically isointense to slightly hypointense to gray matter on T1W-weighted (T1W) images. Gray matter buckling can be seen, a sign of extra-axial location of the tumor ( Fig. 6 ).

On T2W-weighted (T2W) imaging, signal intensity is variable; a central sunburst pattern may be present, which is often correlated with a radial or spoke-wheel pattern of tumor neovascularity. Approximately 80% demonstrate internal flow voids on MR. A variable degree of peritumoral vasogenic edema within the overlying brain ( Fig. 7 ) is common on T2W or FLAIR. This is not directly related to the histology or WHO grade of the tumor but it is indirectly related to prognosis due to its relation to more difficult surgical resectability (the more edema, the more difficult to resect).

Diffusion signal is variable with reports of reduced diffusion in more cellular and/or more aggressive meningioma. Magnetic resonance venography may show occlusion of adjacent dural venous sinuses, especially when the tumor is in proximity to the superior sagittal sinus ( Fig. 4 B).

On angiogram, meningiomas are usually fed primarily by branches of the external carotid but may have dual supply (external > internal carotid), and it is characteristic for an early arterial stain, yet a prominent and persistent tumor blush into the venous phase.

Well-differentiated meningiomas show alanine (ALA) peak on magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) ( Fig. 8 ).

On PET, typical meningiomas are usually hypometabolic compared with cortex. Typical meningiomas, however, may become hypermetabolic after radiation therapy, despite benign histology.

In general, the various imaging features of meningiomas may not accurately reflect the specific histologic subtypes: atypical imaging features do not correspond to atypical histology regarding meningiomas, and typical imaging findings do not exclude atypical variants. But attempts at differentiating typical from atypical/malignant meningioma can be useful for preoperative planning, so attempts must be done from the radiologic viewpoint. Invasion of dura, bone, or scalp; hyperostosis or bone destruction; arterial encasement (often with a narrowed lumen); and peritumoral brain edema are not considered signs of malignant histology but alter the prognosis. Invasion of brain (shallow/microscopic) is considered a grade 2 feature according to WHO 2007 ( Fig. 9 ).

Intratumoral cystic change, prominent tumor lobules extending away from the primary mass (mushrooming) and extracranial extension through foramina are features associated with high-grade (WHO 2–3) meningioma. Elevated relative cerebral blood volume in peritumoral edema on perfusion MR imaging, restricted diffusion with low signal on ADC, low ALA peak on MRS, and hypermetabolic activity in relation to the cortex on PET may be all suggestive of atypical or anaplastic meningioma.

Prognosis depends on WHO grade, tumor location, and completeness of resection. Typical meningioma is a WHO grade 1 tumor that usually follows a benign clinical course. The tumor is slow growing and may grow slowly to compress adjacent structures. The tumor may spread along the dura, invading the adjacent bone, and parasagittal tumors may invade and occlude the superior sagittal sinus. Hematogenous metastases are extremely rare (in 0.1%–0.2%).

Standard treatment is surgical resection. Rarely radiation, including stereotactic radiosurgery for small lesions, may be used. Prognosis is good. Grade 1 meningiomas have a 5-year survival rate of more than 90%. Resection, if complete, is curative without risk of metastatic disease. Local recurrence is estimated at 9% within a median presentation time of 7.5 years. Poor prognostic indicators include local invasion, high rate of mitosis, and anaplastic features.

Atypical histology in meningiomas implies both a higher incidence and shorter time to recurrence: 30% total recurrence rate, with a median time to recurrence of 3 years for atypical meningiomas, and 75% of total recurrence rate with a median time to recurrence of 2 years for anaplastic meningiomas (all less than typical meningioma).

Meningioma

Meningiomas are nonglial and extra-axial dural-based tumors. They are the most common nonglial primary brain and central nervous system (CNS) tumor, accounting for 35% of all histologic reports. The autopsy prevalence is estimated at 1% to 1.5%, and meningiomas are frequent incidentalomas in 1% to 3% of adults screened as volunteers for MR imaging research or during executive physicals that include neuroimaging.

Meningiomas arise from arachnoid meningothelial (cap) cells, especially where arachnoid granulations are numerous (along the dural sinuses).

Classic or typical meningiomas, which account for more than 90% of all meningiomas, including several subtypes (transitional, fibroblastic, and meningothelial), are World Health Organization (WHO) grade 1 neoplasms. Less than 1 in 10 (8.3%) of all meningiomas are atypical meningioma, which are WHO grade 2. Less than 1% are classified as malignant or anaplastic meningioma, WHO grade 3. The subtype of papillary meningioma is also included in WHO grade 3.

Inherited susceptibility to meningioma is suggested by multiplicity, family history (NF2), and sporadic mutations in tumor suppressor genes (chromosome 22q). Atypical and malignant meningiomas incur additional genetic alterations; malignant meningioma typically has reactivation of telomerase or inactivation of CDKN2A.

Ionizing radiation exposure is an established risk factor, and meningiomas are the most common radiation-induced tumors, with a latency of 20 to 35 years after initial radiotherapy.

Because women are twice as likely as men to develop meningiomas, these tumors show a correlation with breast cancer, and they may increase size and/or present during pregnancy. They harbor hormone receptors (progesterone receptors in 66%–88% and estrogen receptors are less common). An etiologic role for female sex hormones (both endogenous and exogenous) has been hypothesized.

Obesity has newly been related to enhanced risk for meningioma.

Head trauma and cell phone use have also been suggested as a risk factor for meningioma, although the results across studies are not consistent in proving these controversial associations.

Approximately 90% of all meningiomas are located above the tentorium. The most common locations include the cerebral convexity, parasagittal/falx, the sphenoid ridge, the olfactory groove, or parasellar-like tuberculum sella. The cerebellopontine angle is the most common place for infratentorial meningiomas, accounting for 8% to 10% of them, and the paranasal sinuses are the most common extracranial location. Meningiomas also represent approximately 25% of all intraspinal tumors.

Data from the Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States demonstrate more than 2-fold higher incidence among women. Age-specific incidence rates reveal increasing risk with age in both men and women (typically arising after age 40). Malignant meningioma occurs 10 years earlier than typical meningiomas. Regarding ethnicity, meningiomas are more common in African Americans.

Meningiomas are usually slow growing and indolent (90%). Small tumors near eloquent cortex may present when small (<3 cm) whereas larger tumors are seen in other locations, such as subfrontal/olfactory groove. Symptoms are dependent on location, and include: seizures, headache, paresis, change in mental status, and sometimes focal neurologic deficits.

There are 2 basic morphologies for meningiomas: globose (well-demarcated spherical/hemispherical mass with a wide dural attachment and convex toward the brain) and en plaque — a carpet-like thickening of the dura, without parenchymal invagination. On gross inspection, the tumors are usually homogenous and often reddish-brown in color ( Fig. 1 ).

There is a wide range of histologic subtypes. Meningothelial is the most common, characterized by uniform tumor cells, collagenous septa, and psammomatous calcifications ( Fig. 2 ). Other common subtypes include fibrous, transitional, lipoblastic, and microcystic (also called humid).

Typical diagnostic features are seen on imaging in 75% of all meningiomas ( Box 1 ), including a sharply circumscribed and homogenous extra-axial mass with a broad-based dural attachment ( Fig. 3 ). Calcification is occasionally seen in approximately 25%. Necrosis, cysts, and hemorrhage are less frequently present. Most meningiomas have a clearly demonstrable cleavage plane that separates them from underlying brain and facilitates surgery. On MR imaging, especially, trapped cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or vessels are often seen in a cleft between the mass and the brain.

Imaging tips

Best modality: MR imaging with contrast. CT: look for typical bone hyperostosis and calcium within the lesion. MRS: might be useful in uncertain cases (ALA peak for well-differentiated and lower ADC with increased cellularity).

Differential diagnosis

HPC: bone destruction, not calcified, lobulated, and narrow dural based

Dural metastasis: skull first affected, multifocal

Granulomatous diseases: multifocal

Pearls, pitfalls, and variants

Atypical meningioma: invasion of brain (shallow/microscopic)

Anaplastic meningioma: intratumoral cystic change, prominent tumor pannus extending away from mass (mushrooming), extracranial extension through foramina

Atypical imaging features do not correspond to atypical histology.

What the referring physician needs to know

Vascular supply: plan need of presurgical embolization

Bone/dural extension and relation between meningioma and brain parenchyma (CSF cleft? Apparent infiltration?): plan surgical strategy to achieve a complete tumoral resection (including bone and dura affected).

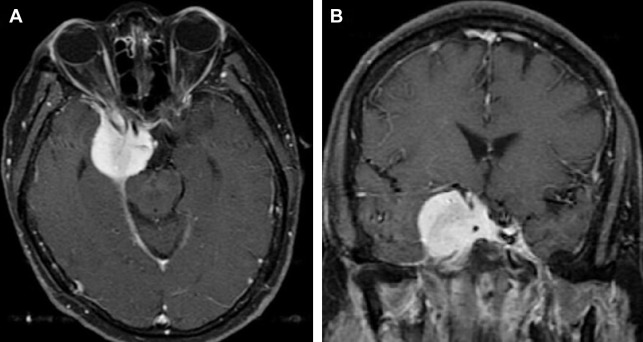

On noncontrast CT, typical meningioma is isodense (25%) or hyperdense (75%) to gray matter. Most (>90%) show intense, homogeneous enhancement on postcontrast CT imaging, with a dural tail (on both CT and MR imaging). The dural tail is not a specific feature but is typical of meningiomas and it usually represents reactive vascular changes and dural edema ( Fig. 4 A ).

Intraosseous extension may be evidenced by irregular cortical margins in the skull, hyperostosis, and increased bone vascularity ( Fig. 5 ). Hyperostosis is present in 25% to 60% (or more) of meningiomas and may occur with or without microscopic invasion of the bone.

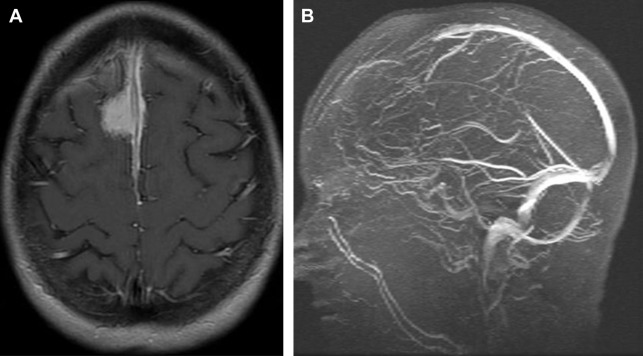

On MR imaging, meningioma is typically isointense to slightly hypointense to gray matter on T1W-weighted (T1W) images. Gray matter buckling can be seen, a sign of extra-axial location of the tumor ( Fig. 6 ).

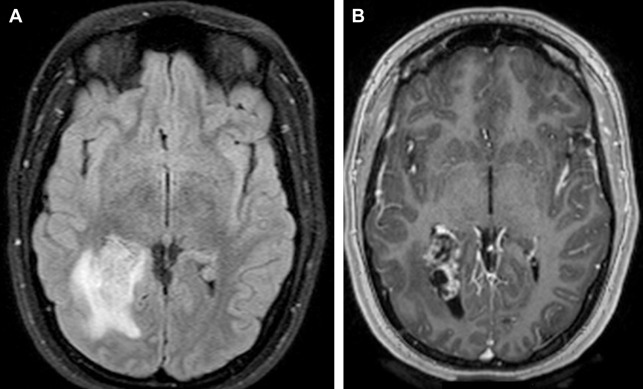

On T2W-weighted (T2W) imaging, signal intensity is variable; a central sunburst pattern may be present, which is often correlated with a radial or spoke-wheel pattern of tumor neovascularity. Approximately 80% demonstrate internal flow voids on MR. A variable degree of peritumoral vasogenic edema within the overlying brain ( Fig. 7 ) is common on T2W or FLAIR. This is not directly related to the histology or WHO grade of the tumor but it is indirectly related to prognosis due to its relation to more difficult surgical resectability (the more edema, the more difficult to resect).

Diffusion signal is variable with reports of reduced diffusion in more cellular and/or more aggressive meningioma. Magnetic resonance venography may show occlusion of adjacent dural venous sinuses, especially when the tumor is in proximity to the superior sagittal sinus ( Fig. 4 B).

On angiogram, meningiomas are usually fed primarily by branches of the external carotid but may have dual supply (external > internal carotid), and it is characteristic for an early arterial stain, yet a prominent and persistent tumor blush into the venous phase.

Well-differentiated meningiomas show alanine (ALA) peak on magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) ( Fig. 8 ).

On PET, typical meningiomas are usually hypometabolic compared with cortex. Typical meningiomas, however, may become hypermetabolic after radiation therapy, despite benign histology.

In general, the various imaging features of meningiomas may not accurately reflect the specific histologic subtypes: atypical imaging features do not correspond to atypical histology regarding meningiomas, and typical imaging findings do not exclude atypical variants. But attempts at differentiating typical from atypical/malignant meningioma can be useful for preoperative planning, so attempts must be done from the radiologic viewpoint. Invasion of dura, bone, or scalp; hyperostosis or bone destruction; arterial encasement (often with a narrowed lumen); and peritumoral brain edema are not considered signs of malignant histology but alter the prognosis. Invasion of brain (shallow/microscopic) is considered a grade 2 feature according to WHO 2007 ( Fig. 9 ).

Intratumoral cystic change, prominent tumor lobules extending away from the primary mass (mushrooming) and extracranial extension through foramina are features associated with high-grade (WHO 2–3) meningioma. Elevated relative cerebral blood volume in peritumoral edema on perfusion MR imaging, restricted diffusion with low signal on ADC, low ALA peak on MRS, and hypermetabolic activity in relation to the cortex on PET may be all suggestive of atypical or anaplastic meningioma.

Prognosis depends on WHO grade, tumor location, and completeness of resection. Typical meningioma is a WHO grade 1 tumor that usually follows a benign clinical course. The tumor is slow growing and may grow slowly to compress adjacent structures. The tumor may spread along the dura, invading the adjacent bone, and parasagittal tumors may invade and occlude the superior sagittal sinus. Hematogenous metastases are extremely rare (in 0.1%–0.2%).

Standard treatment is surgical resection. Rarely radiation, including stereotactic radiosurgery for small lesions, may be used. Prognosis is good. Grade 1 meningiomas have a 5-year survival rate of more than 90%. Resection, if complete, is curative without risk of metastatic disease. Local recurrence is estimated at 9% within a median presentation time of 7.5 years. Poor prognostic indicators include local invasion, high rate of mitosis, and anaplastic features.

Atypical histology in meningiomas implies both a higher incidence and shorter time to recurrence: 30% total recurrence rate, with a median time to recurrence of 3 years for atypical meningiomas, and 75% of total recurrence rate with a median time to recurrence of 2 years for anaplastic meningiomas (all less than typical meningioma).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree