Extraparenchymal lesions of childhood include neoplastic and nonneoplastic entities. Lesions affecting children are different from the most common entities affecting adults. Although there are imaging features that are highly suggestive of extraparenchymal origin, it can be difficult to distinguish extraparenchymal from intraparenchymal lesions. MR imaging is the examination of choice for the evaluation of extraparenchymal lesions given greater sensitivity and anatomic detail. Syndromic associations should be considered, especially for unusual lesions in the pediatric age group such as meningioma and schwannoma.

Key points

- •

The differential diagnosis for extraparenchymal lesions in the pediatric age group differs from that in adults.

- •

Etiology can be either neoplastic or nonneoplastic.

- •

Be aware of concerning clinical symptoms necessitating imaging.

Introduction

Extraparenchymal lesions are those arising from intracranial structures other than the brain parenchyma. When a mass is diagnosed, it is key to identify features suggesting whether the lesion arises from the brain parenchyma or from the extraparenchymal structures, because the origin and location of the tumor can guide treatment, including determination of the resectability of the lesion, surgical approach, and prognosis. However, the differentiation of intraparenchymal lesions from extraparenchymal lesions can be challenging, and close attention to the imaging features of the mass lesions is required.

The etiology of extraparenchymal lesions is variable. They include both true neoplasms as well as congenital lesions. Neoplasms may be either benign or malignant, and either primary or metastatic, although metastatic disease is less common in children than adults. On this note, the common lesions affecting the extraparenchymal structures in the pediatric population differ from the common entities encountered in the adult population. As such, age plays an important role in the differential diagnosis and evaluation of these lesions.

In children, dominant symptoms depend on the age and location of the tumor. Infants may present with increasing head circumference, lethargy, and vomiting. Older children may also report headaches, worsening school performance, and focal neurologic deficits, including cranial nerve palsies ( Box 1 ).

- •

Headaches

- •

Elevated intracranial pressure, with or without accompanying hydrocephalus

- •

Cognitive symptoms/impairment

- •

Neurologic deficits, varying depending on the location of the tumor

- •

Seizures

- •

Endocrine abnormality

- •

Cranial nerve palsies

Symptoms may progress rapidly, especially in the context of an aggressive, rapidly growing tumor, or may progress slowly over time when tumors are slow growing and less aggressive. Because some of the associated symptoms are common and nonspecific, in particular headaches, determining when it is appropriate to consider imaging to evaluate for an underlying lesion can be a clinical challenge. Some guidelines for imaging have been suggested in the literature, with concerning predictors for central nervous system lesions summarized in Box 2 . The greater the number of predictors present, the greater the risk of an underlying surgical lesion.

Headaches persisting for less than 6 months without response to treatment

Headache associated with neurologic findings

Persistent headaches without family history of migraines a

Headache associated with emesis, disorientation, or confusion

Headaches either occurring on awakening or awakening patient from sleep a

Family history or medical history of disorders predisposing to CNS lesions with clinical or laboratory findings suggesting a CNS lesion

Abbreviation: CNS, central nervous system.

a Sleep-related headache and no family history of migraine are the strongest predictors.

Introduction

Extraparenchymal lesions are those arising from intracranial structures other than the brain parenchyma. When a mass is diagnosed, it is key to identify features suggesting whether the lesion arises from the brain parenchyma or from the extraparenchymal structures, because the origin and location of the tumor can guide treatment, including determination of the resectability of the lesion, surgical approach, and prognosis. However, the differentiation of intraparenchymal lesions from extraparenchymal lesions can be challenging, and close attention to the imaging features of the mass lesions is required.

The etiology of extraparenchymal lesions is variable. They include both true neoplasms as well as congenital lesions. Neoplasms may be either benign or malignant, and either primary or metastatic, although metastatic disease is less common in children than adults. On this note, the common lesions affecting the extraparenchymal structures in the pediatric population differ from the common entities encountered in the adult population. As such, age plays an important role in the differential diagnosis and evaluation of these lesions.

In children, dominant symptoms depend on the age and location of the tumor. Infants may present with increasing head circumference, lethargy, and vomiting. Older children may also report headaches, worsening school performance, and focal neurologic deficits, including cranial nerve palsies ( Box 1 ).

- •

Headaches

- •

Elevated intracranial pressure, with or without accompanying hydrocephalus

- •

Cognitive symptoms/impairment

- •

Neurologic deficits, varying depending on the location of the tumor

- •

Seizures

- •

Endocrine abnormality

- •

Cranial nerve palsies

Symptoms may progress rapidly, especially in the context of an aggressive, rapidly growing tumor, or may progress slowly over time when tumors are slow growing and less aggressive. Because some of the associated symptoms are common and nonspecific, in particular headaches, determining when it is appropriate to consider imaging to evaluate for an underlying lesion can be a clinical challenge. Some guidelines for imaging have been suggested in the literature, with concerning predictors for central nervous system lesions summarized in Box 2 . The greater the number of predictors present, the greater the risk of an underlying surgical lesion.

Headaches persisting for less than 6 months without response to treatment

Headache associated with neurologic findings

Persistent headaches without family history of migraines a

Headache associated with emesis, disorientation, or confusion

Headaches either occurring on awakening or awakening patient from sleep a

Family history or medical history of disorders predisposing to CNS lesions with clinical or laboratory findings suggesting a CNS lesion

Abbreviation: CNS, central nervous system.

a Sleep-related headache and no family history of migraine are the strongest predictors.

Normal anatomy and imaging technique

Key anatomic locations to examine for extraparenchymal lesions are the ventricles, subarachnoid spaces, and meninges. If a lesion is extraparenchymal, there should be a margin between the lesion and the underlying brain. Typically, the underlying brain parenchyma will be displaced by an extraparenchymal lesion, rather than infiltrated or replaced by it, as with intraparenchymal lesions. Extraparenchymal lesions usually result in less parenchymal edema than lesions arising from the brain parenchyma itself. In addition, an extraparenchymal lesion may result in less mass effect relative to its size than an intraparenchymal lesion. Other features suggestive of an extraparenchymal rather than intraparenchymal lesion include involvement of bone, crossing the midline without involvement of cerebral commissures, and less severe presenting symptoms.

When considering imaging technique, MR imaging is preferable to computed tomography (CT) scanning for the evaluation of intracranial masses. MR imaging has greater sensitivity, especially in the subarachnoid spaces and posterior fossa, greater ability to differentiate tumor from normal structures, better ability to characterize tissues, and superior capability to determining tumor extent compared with SCT scanning.

If CT scanning is performed, noncontrast imaging is highly valuable for assessment of the presence of hemorrhage and calcifications. Noncontrast imaging also allows for assessment of tumor density, which is a surrogate for tumor cellularity. Highly cellular tumors should be hyperdense on CT scanning, whereas less cellular tumors are less dense. CT scans can also suggest the presence of fat.

MR imaging protocols should include at least T1-weighted, T2-weighted, diffusion-weighted, gradient echo or susceptibility weighted imaging, and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery imaging, as well as postcontrast T1-weighted imaging in multiple planes. Other potentially useful sequences include high-resolution T2-weighted sequences and volumetric T1-weighted sequences, because these studies can allow greater anatomic definition of tumor involvement regarding size, extent, and more direct visualization of the tissues involved ( Table 1 ).

| CT | MR imaging |

|---|---|

| Noncontrast | Multiplanar imaging should include T1, T2, FLAIR, diffusion, GRE or SWI, and postcontrast T1 |

| Postcontrast can be considered, but usually is not needed because MR imaging provides more information and is usually performed. | Additional sequences such as high resolution T2-weighted and volumetric T1-weighted images may be helpful. |

Imaging findings and pathology

Extraparenchymal Lesions in Childhood

- •

Choroid plexus tumors

- •

Dermoid/epidermoid

- •

Arachnoid cysts

- •

Meningiomas (rare in childhood)

- •

Schwannomas (rare in childhood)

- •

Lymphoma/leukemia

- •

Miscellaneous

Choroid Plexus Tumors

Choroid plexus tumors arise from the epithelium of the choroid plexus. This category includes choroid plexus papillomas (World Health Organization grade I), atypical choroid plexus papillomas (World Health Organization grade II), and choroid plexus carcinomas (World Health Organization grade III). Radiologically, these entities cannot be distinguished accurately, and diagnosis must be made on histology. However, papillomas outnumber carcinomas by approximately 5:1. Choroid plexus tumors are rare, accounting for only 2% to 6% of pediatric brain tumors. Choroid plexus tumors in children most commonly arise in the lateral ventricles. Although they can occur at any age, choroid plexus papillomas usually present by 5 years of age in the pediatric population, and the most common reason for their discovery is severe hydrocephalus. Hydrocephalus can occur in up to 80% of cases, and likely results from both overproduction of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) by the tumor and impaired resorption, as well as obstruction.

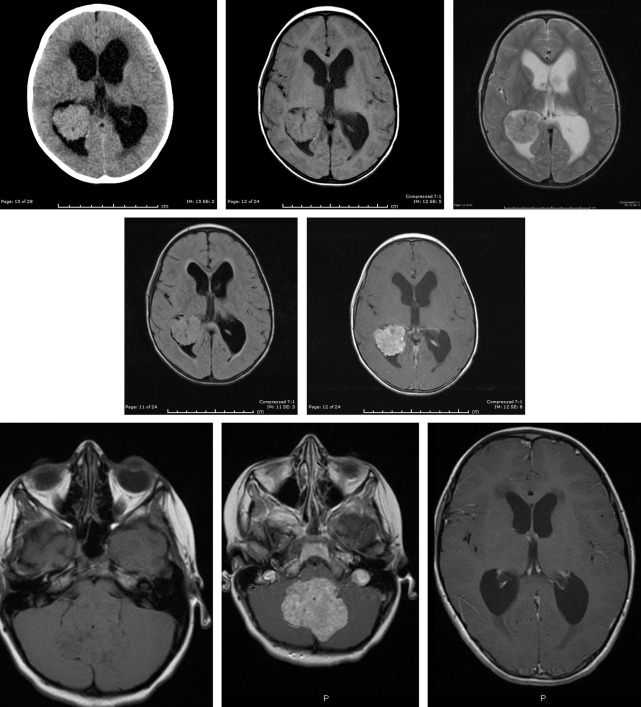

Choroid plexus papillomas have variable CT appearance, and can be isodense or hyperdense. Calcifications can be present. They are lobulated, and enhance homogeneously. On MR imaging ( Fig. 1 ), they have a papillary appearance with branching pattern and may have cysts, septatations and/or, calcification. Hemorrhage may be demonstrated, especially in atypical choroid plexus papillomas and choroid plexus carcinomas. They enhance avidly. When arising in the fourth ventricle, they can extend through the outlet foramina and present as a cerebellopontine angle mass. Although there is considerable overlap in appearance between choroid plexus papillomas and carcinomas, features suggestive of carcinoma include increased heterogeneity, ill-defined margins, loss of branching pattern, restricted diffusion, and very high choline in the spectroscopy, owing to high cell density ( Fig. 2 ). Because choroid plexus carcinomas can metastasize, imaging of the spine should be performed to evaluate for leptomeningeal spread.

Choroid Plexus Tumors

- •

Hydrocephalus is a key feature.

- •

Choroid plexus papilloma, atypical choroid plexus papilloma and carcinoma may be indistinguishable by imaging, but papillomas are much more common.

- •

Histology is needed for definitive diagnosis.

- •

Avidly enhancing masses, most commonly in the lateral ventricles.

- •

Consider spine imaging to evaluate for metastatic disease.