Anatomy

This chapter is different from other chapters, in that there may be a variety of causes and different anatomic regions may be the etiology of pain in later pregnancy. As for anatomic considerations, the main focus of this chapter will be on obstetrical etiologies of pain and/or bleeding. Much of the focus will be on the placenta, cervix, umbilical cord, and amniotic fluid. During the second and third trimesters of pregnancy, the fetus continues to grow with concomitant changes in the placenta that connects the fetus to the uterus. The placenta develops from the chorion frondosum that has developed from the blastocyst of the embryo. It is attached to the uterus via the decidua basalis (from the maternal placenta). The placenta is the connection between the maternal circulation and the fetal circulation and allows for exchange of oxygen and nutrients between mother and fetus. The location of the placenta and its relationship to the cervix are important and will be discussed in more detail. The cervical is closed during pregnancy and effaces and shortens before birth. Premature opening of the cervix, placental abnormalities, and the relationship of the placenta to the cervix will be discussed in more detail in this chapter.

The umbilical cord is composed of one vein flowing toward the fetus and two arteries flowing from the fetus to the placenta. Normally, the umbilical cord should insert in the more central portion of the placenta. If the cord inserts on the placenta edge or is the presenting part during delivery, this can have devastating consequences on the pregnancy.

Amniotic fluid volume is dependent on the balance between the production and removal of amniotic fluid. In the second and third trimesters of pregnancy, the major source of fluid is production of urine by the fetal kidneys. In late pregnancy, amniotic fluid is reabsorbed into the gastrointestinal tract after fetal swallowing. Amniotic fluid is important for the well-being of the fetus.

Ultrasound Techniques/Findings

Placenta

The placenta appears uniform in echotexture and thickness between the eighth and twentieth weeks of pregnancy. At that time the placenta measures up to 3 cm in thickness. Later in pregnancy the placenta usually measures less than 4 cm in thickness. However, there may be myometrial contractions in which the placenta may appear artificially thickened. Later in pregnancy hypoechoic regions may develop within the placenta, as “placental lakes.” There may be other hypoechoic regions within the placenta, most of which are benign in etiology.

The placenta is usually attached in the mid-to-fundal portion of the uterus. Identification of the location of the placenta and its relationship to the cervix is of utmost importance. Overdistention of the urinary bladder and/or focal uterine contractions may give the false impression of a placenta previa by compressing the lower portion of the uterus.

The placenta is separated from the myometrium by a subplacental venous complex called the decidua basalis . This is a few millimeters in thickness and has different appearances depending on the location of the placenta. The decidua basalis is important to visualize because, with placenta accreta, placental tissue invades through this region into the myometrium.

Umbilical Cord

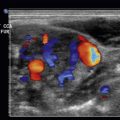

The placenta can be scanned and color flow may be utilized to identify the insertion of the cord into the placenta. Routine visualization of the location of the cord into the placenta is essentially the diagnosis of marginal and velamentous insertion of the umbilical cord. Color flow imaging is helpful in this identification and following the very circuitous course of the umbilical cord. Also important in the third trimester of pregnancy is to examine the cervix with color to make sure the umbilical cord does not overlay the cervical os.

Cervix

The appearance of the cervix is important when evaluating a patient with pain or bleeding in the second or third trimester of the pregnancy. Abdominal ultrasound examination of the cervix often may be difficult because of myometrial contractions or fetal parts overlying the lower portion of the uterus/cervix. In these cases translabial or transvaginal techniques may be helpful to image the cervix when the transabdominal approach is unsuccessful. Translabial scanning is performed with the patient’s bladder empty. A sterile glove or cover is placed over the probe using this approach. The translabial approach is useful to exclude placenta previa. Endovaginal scanning with the bladder partially full may be helpful when evaluating for such abnormalities as placenta previa or placenta accreta. These entities will be discussed in more detail later in the chapter. Cervical incompetence, shortening of the cervix, mild dilatation of the endocervical canal, or bulging of the amniotic membranes may be diagnosed with the transabdominal technique, but in many cases translabial and/or endovaginal scanning may be needed.

Amniotic Fluid

Amniotic fluid volume can be assessed quantitatively or qualitatively by ultrasound. Subjective assessment of amniotic fluid by an experienced examiner is usually as good as quantitative measurements of amniotic fluid volume. Quantitative measurements for amniotic fluid include an amniotic fluid index (AFI). The AFI is obtained by assessing the four quadrants of the uterus for the deepest vertical pocket in centimeters and adding the sum of these four measurements. AFI measurements are approximately 12 cm throughout pregnancy. The upper limits of normal is 24 cm, and the lower limits of normal are from 5 to 8 cm. A second method of quantitative detection of amniotic fluid is by the single deepest pocket method, called maximum vertical pocket (MVP). The single deepest pocket is considered too small if less than 2 cm and too large if greater than 8 cm.

Abdominal Pain in Pregnancy

In many situations, pain in later pregnancy may be secondary to relatively harmless etiologies such as Braxton-Hicks contractions, round ligament pain, or constipation. However, there are more serious gynecologic and nongynecologic causes of abdominal pain in pregnancy. The nongynecologic causes of pain in pregnancy will be briefly discussed. However, these causes are discussed in more detail in specific anatomic chapters 16-19 . Pain in pregnancy is problematic, as there are two patients. In all pregnant patients with abdominal pain there should always be careful maternal and fetal monitoring, including checking the fetal heart rate. As there are concerns about radiation to the fetus, in most situations, ultrasound is the first imaging study performed on these patients. The nongynecologic etiologies of pain in the third trimester of pregnancy can include acute appendicitis, acute cholecystitis, obstructive renal calculi, bowel obstruction, ovarian torsion, and, rarely, pancreatitis. Right lower quadrant pain may be secondary to acute appendicitis or renal colic. In pregnancy, the appendix may be difficult to image. Typical findings include a blind-ending, noncompressible, tubular structure greater than 6 mm in diameter. There may be mesenteric standing, free fluid, and a possible appendicolith. If there is strong suspicion of appendicitis and the ultrasound is nondiagnostic, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) would be the next imaging choice.

For pregnant patients with renal colic, the stones may be difficult to identify, but ultrasound may be used to identify the accompanying hydronephrosis. Color flow of the bladder may be useful to look for ureteral jets. This is discussed in more detail in Chapter 19 , on the kidney. In critical situations low-dose, noncontrast computed tomography (CT) may be utilized.

Suspected acute cholecystitis is imaged by ultrasound. Findings have been previously discussed in Chapter 17 , on the gallbladder and biliary tract. Other suspected nongynecologic causes of pain in pregnancy are rarer. These are discussed in other chapters. In some situations, low-dose CT may be needed to determine the etiology of pain.

Patients in the third trimester who have preeclampsia may develop hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets called the HELLP syndrome . These patients may present with vague symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, headache, and malaise. Diagnosis is made on clinical presentation and laboratory values showing hemolysis, low platelet count, and elevated biliary enzymes. Very rarely, these patients can develop hepatic hemorrhage and ruptures. Liver ultrasound findings include hypoechoic-to-heterogeneous intraparenchymal and perihepatic hematomas. CT may be used in these cases. The syndrome usually resolves with delivery of the fetus.

Abdominal Pain in Pregnancy

In many situations, pain in later pregnancy may be secondary to relatively harmless etiologies such as Braxton-Hicks contractions, round ligament pain, or constipation. However, there are more serious gynecologic and nongynecologic causes of abdominal pain in pregnancy. The nongynecologic causes of pain in pregnancy will be briefly discussed. However, these causes are discussed in more detail in specific anatomic chapters 16-19 . Pain in pregnancy is problematic, as there are two patients. In all pregnant patients with abdominal pain there should always be careful maternal and fetal monitoring, including checking the fetal heart rate. As there are concerns about radiation to the fetus, in most situations, ultrasound is the first imaging study performed on these patients. The nongynecologic etiologies of pain in the third trimester of pregnancy can include acute appendicitis, acute cholecystitis, obstructive renal calculi, bowel obstruction, ovarian torsion, and, rarely, pancreatitis. Right lower quadrant pain may be secondary to acute appendicitis or renal colic. In pregnancy, the appendix may be difficult to image. Typical findings include a blind-ending, noncompressible, tubular structure greater than 6 mm in diameter. There may be mesenteric standing, free fluid, and a possible appendicolith. If there is strong suspicion of appendicitis and the ultrasound is nondiagnostic, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) would be the next imaging choice.

For pregnant patients with renal colic, the stones may be difficult to identify, but ultrasound may be used to identify the accompanying hydronephrosis. Color flow of the bladder may be useful to look for ureteral jets. This is discussed in more detail in Chapter 19 , on the kidney. In critical situations low-dose, noncontrast computed tomography (CT) may be utilized.

Suspected acute cholecystitis is imaged by ultrasound. Findings have been previously discussed in Chapter 17 , on the gallbladder and biliary tract. Other suspected nongynecologic causes of pain in pregnancy are rarer. These are discussed in other chapters. In some situations, low-dose CT may be needed to determine the etiology of pain.

Patients in the third trimester who have preeclampsia may develop hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets called the HELLP syndrome . These patients may present with vague symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, headache, and malaise. Diagnosis is made on clinical presentation and laboratory values showing hemolysis, low platelet count, and elevated biliary enzymes. Very rarely, these patients can develop hepatic hemorrhage and ruptures. Liver ultrasound findings include hypoechoic-to-heterogeneous intraparenchymal and perihepatic hematomas. CT may be used in these cases. The syndrome usually resolves with delivery of the fetus.

Obstetric Causes of Pain or Bleeding in Late Pregnancy

Many of the obstetric etiologies of pain or bleeding in pregnancy are emergencies, which may require prompt action and special expertise. Some causes, such as ovarian torsion, are more frequent in the first trimester of pregnancy. These etiologies will be discussed in Chapters 23 and 24 . Pain or bleeding in later pregnancy may be due to a number of different etiologies. Many women have discomfort during later pregnancy due to fairly harmless etiologies. This was previously discussed and can include discomfort or pain due to Braxton-Hicks contractions, round ligament stretching, back pain, or constipation. Obviously, identification of the etiology of abdominal pain or bleeding in the third trimester is of utmost urgency. In all situations both maternal and fetal monitoring are important. Training modules have advocated obtaining fetal heart rate, fetal head position, and estimated gestational age on an emergent ultrasound examination in later pregnancy. The examination must then be tailored for each clinical situation. More severe causes of pain or bleeding in the second or third trimester of pregnancy can include the following:

Placenta Previa

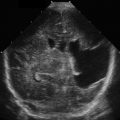

Placental localization is important throughout pregnancy, but it is especially important in the third trimester of pregnancy, particularly if the patient presents with pain, bleeding, or active labor. The distance from the edge of the placenta to the internal cervical os can be measured on transabdominal scan but is best evaluated on endovaginal scanning. There are different subtypes of placenta previa ( Fig. 25.1 ). These include a low-lying placenta, where the lower margin of the placenta is within 2 cm of the internal cervical os. The term marginal placenta previa and partial placenta previa are no longer used. A complete placenta previa is where the placenta covers the internal os ( Fig. 25.2 , ![]() Videos 25.1 and 25.2 ). A central previa is where the placenta is implanted centrally, directly over the internal os. In evaluating placenta previa, one must remember that the placenta is not only anterior and posterior but may extend from the side close to and/or over the endocervical canal. If fetal parts obscure visualization of the cervix, translabial or endovaginal scanning may be helpful. There are several pitfalls in the diagnosis of placenta previa. Myometrial contractions in the lower uterine segment may mimic a placenta previa. Additionally, if the bladder is overdistended there may be a false-positive diagnosis of placenta previa. In cases where there is doubt about placenta previa, endovaginal scanning is very helpful ( Fig. 25.3 ,

Videos 25.1 and 25.2 ). A central previa is where the placenta is implanted centrally, directly over the internal os. In evaluating placenta previa, one must remember that the placenta is not only anterior and posterior but may extend from the side close to and/or over the endocervical canal. If fetal parts obscure visualization of the cervix, translabial or endovaginal scanning may be helpful. There are several pitfalls in the diagnosis of placenta previa. Myometrial contractions in the lower uterine segment may mimic a placenta previa. Additionally, if the bladder is overdistended there may be a false-positive diagnosis of placenta previa. In cases where there is doubt about placenta previa, endovaginal scanning is very helpful ( Fig. 25.3 , ![]() Videos 25.3 and 25.4 ).

Videos 25.3 and 25.4 ).