FIBROUS DYSPLASIA AND OTHER FIBRO-OSSEOUS LESIONS OF BONE

KEY POINTS

- Fibro-osseous lesions are usually pathologically indistinguishable from one another.

- Some of these conditions have different clinical implications, even though they are histologically benign.

- Some fibro-osseous lesions are syndromic, and some associated are with endocrine dysfunction.

- These lesions can create compressive cranial neuropathies

- Clinical issues usually center on proper differential diagnosis and cosmetic and mechanical functional problems.

- Imaging is central to sorting out these clinical issues.

- These lesions may grow rapidly under hormonal stimulation during adolescence and pregnancy.

- Ossifying fibromas have several names, and it is wise to be aware of the entity referred to as juvenile active or aggressive ossifying fibroma even though its existence as a separate entity is debated.

- Pathology of bone lesions should almost always be read together with the imaging findings to produce the best diagnoses and to optimize medical decision making.

GENERAL CLINICAL PERSPECTIVE AND PATHOLOGY

The fibromatoses and nonosseous fibrous lesions of histiocytic origin, as well as fibrosarcoma, are discussed separately in Chapter 37. This discussion encompasses a group of lesions that includes the idiopathic growth disorder fibrous dysplasia and a group of fibro-osseous lesions of bone that essentially go by several names that can be quite confusing and encompasses both neoplasms and reactive processes.

The unifying concept of a fibro-osseous lesion is useful to keep the diagnostic imager from being unduly confused by what often seems to be different names for things that may look alike even with careful analysis. This concept is also discussed in comparing and contrasting the various osseous matrices and reactive bony changes in Chapter 12 (Figs. 12.34–12.38). These abnormalities are characterized by the replacement of normal bony architecture with collagen, fibroblasts, and varying amounts of mineralized and more frankly calcified and ossified matrix. This is likely related to the osteoblast being developed along the fibrocyte cell lineage. Histopathologically, tissue from any of these fibro-osseous lesions may look alike. It is the clinical situation and pattern of growth that may determine its specific label. There are some of these that merit possible distinction as a clinical entity because of a more aggressive than average clinical course such as the juvenile active or aggressive ossifying fibroma (JAOF).

Fibro-osseous lesions almost of any type in the proper position can produce secondary mucoceles that can further complicate an already complex imaging appearance in some cases. These lesions can also disrupt the skull base and cause secondary intracranial infections that may complicate the imaging analysis as well as the clinical presentation.

FIBROUS DYSPLASIA

Clinical Perspective and Pathology

The fibromatoses and nonosseous fibrous lesions of histiocytic origin, as well as fibrosarcoma, are discussed separately in Chapter 37. A more general discussion of fibro-osseous lesions is available in the previous section of this chapter.

Fibrous dysplasia of the cranial and facial bones is usually an isolated monostotic phenomenon, although it can be part of a more widespread polyostotic process and associated with endocrine problems, as with Albright syndrome.1 It is a developmental abnormality of the bone forming mesenchyme that results in a disordered maturation and ossification pathway resulting in an anatomically dysmorphic bone. The medullary component of the affected bone is filled with fibrous tissue, and the trabeculae of woven bone contain cystic zones in a collagenous fibrous matrix.

The cranial facial form of the disease is very common. It has no sex predilection and can present at any age. It is often discovered incidentally on imaging studies done for unrelated complaints. The maxilla, mandible, frontal, temporal, parietal, and sphenoid bones may be involved2 (Figs. 40.1–40.6). Isolated areas in the sphenoid bone are often detected as bright areas in the base of the sphenoid bone on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) as incidental findings3 (Fig. 40.5). These may need to be differentiated from areas of fat in the skull base or zones of arrested sphenoid sinus aeration or skull base transition in preparation for sphenoid sinus aeration. Whatever the case, such areas are almost always of low biologic activity and will be of no ultimate consequence to the patient. If multifocal (Fig. 40.6) or polyostotic noncontiguous disease is present, a syndromic association may be considered.

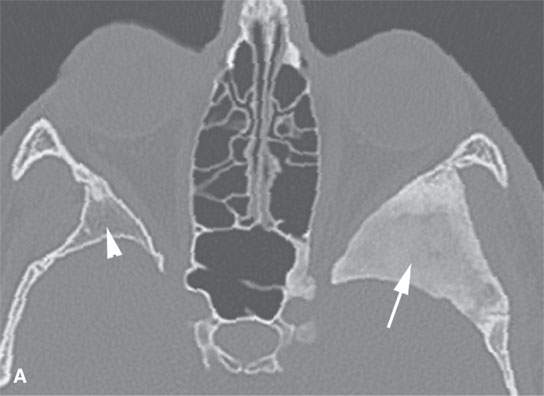

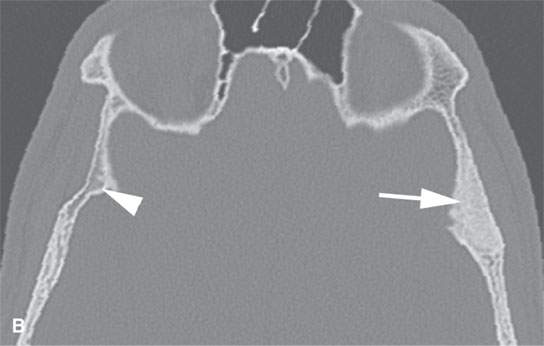

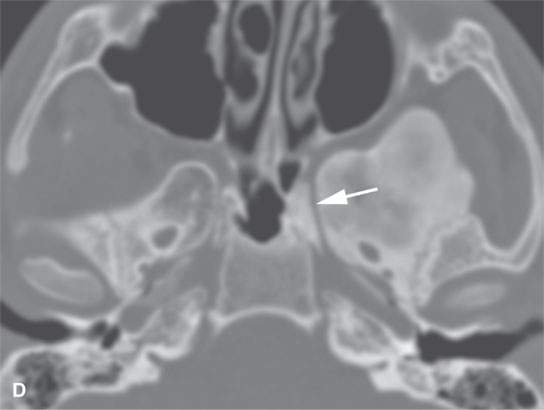

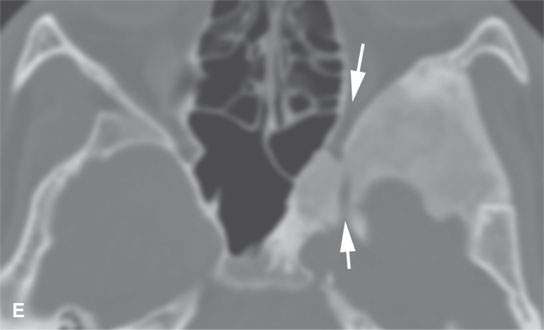

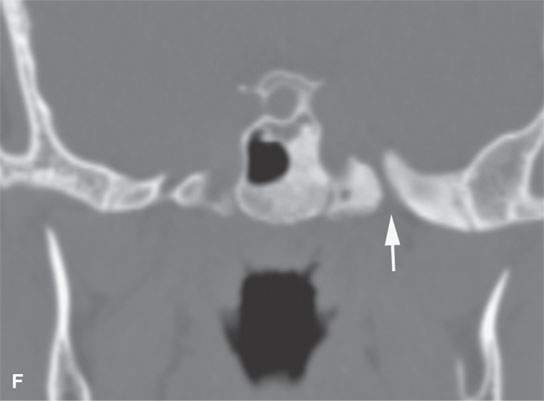

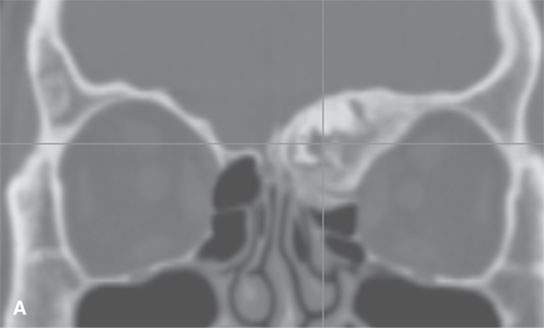

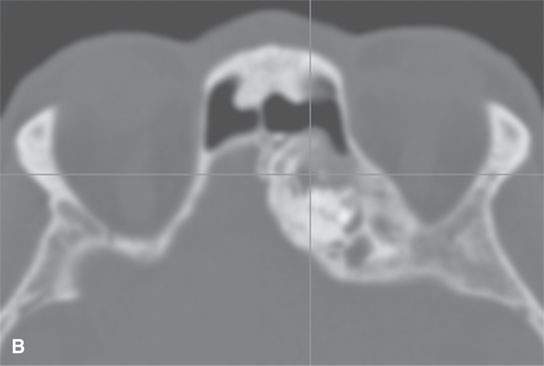

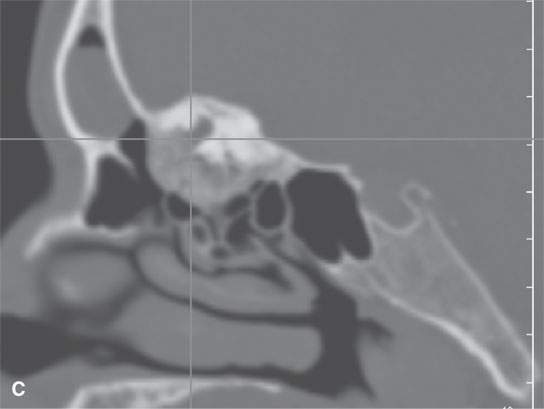

FIGURE 40.1. Computed tomography study of a patient with “classic”-appearing fibrous dysplasia. A, B: These images demonstrate the variety of fibrous dysplasia that shows a generally expanded appearance of bone with a relatively homogeneously mineralized fibrous matrix. Compared the normal (arrowheads) to abnormal (arrows) sides. C–F: These images illustrate the capacity for fibrous dysplasia to narrow various neural foramina and canals (arrows). It also shows that while the matrix may be diffusely mineralized, it will almost show some degree of variability.

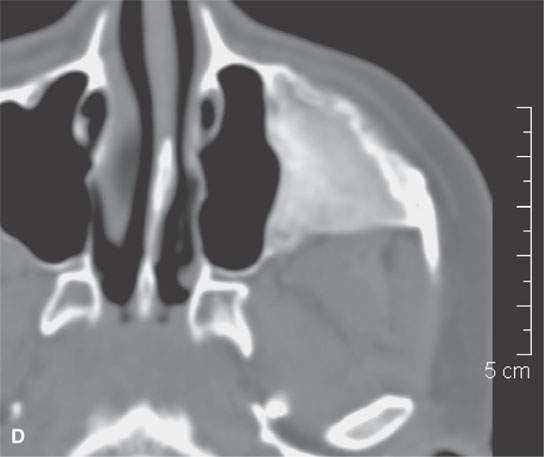

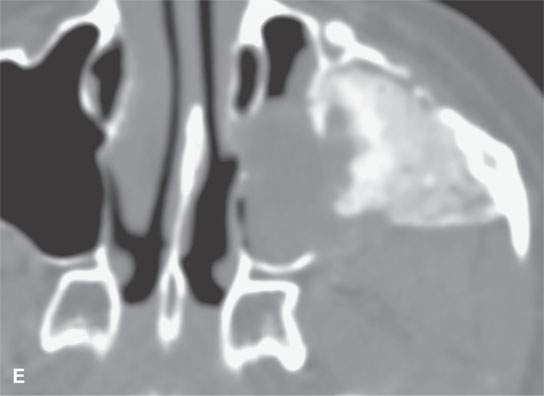

FIGURE 40.2. Computed tomography study of a patient with fibrous dysplasia to show variability in matrix mineralization. A–C: Note that while even though the matrix is highly variable in density, as it is seen throughout the generally expansile lesion some of the areas appear nonmineralized. This lesion was also producing obstructive changes of the frontal sinus.

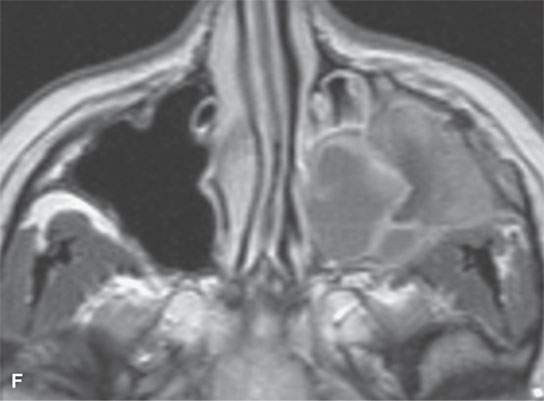

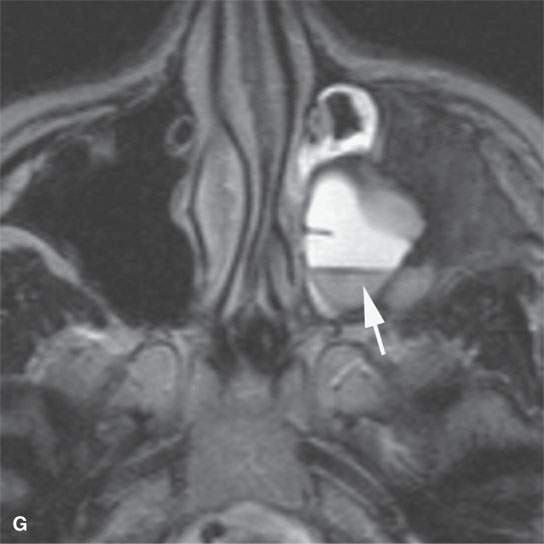

FIGURE 40.3. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance (MR) imaging of a patient with long-standing fibrous dysplasia of the maxilla. The patient had been followed for many years as a child having had multiple cosmetic procedures because of the fibrous dysplasia. During her pregnancy as a young adult, the lesion demonstrated rapid progression. The rapid growth of this lesion stopped and regressed once the patient’s baby was successfully delivered. A, B: Images showing the long-term relatively static fibrous dysplasia on a baseline study (A); the image in (B) shows the essentially nonmineralized portion of the rapidly progressing part of the lesion. C: T1-weighted (T1W) MR image shows the more rapidly progressive part of the lesion to be likely partially hemorrhagic (this is also illustrated in F and G). D, E: Comparison images before and after rapid growth, respectively, for comparison to the MR images in (F) and (G). F, G: ARE[SF1] T1W contrast-enhanced and T2-weighted images, respectively, showing that the soft tissue component of the lesion that grew rapidly likely in response to a hormonal stimulation during pregnancy to have become cystic and hemorrhagic and more enhancing than the remaining areas of fibrous dysplasia. The arrow in (G) shows a fluid level likely related to old blood products.

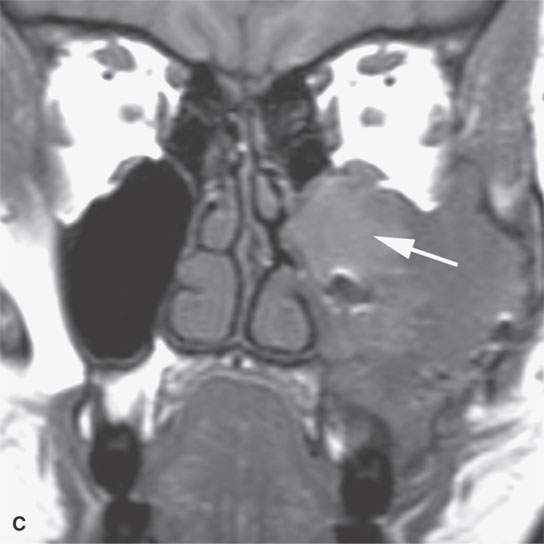

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree