FLUID COLLECTIONS, CYSTS, AND HEMATOMAS

KEY POINTS

- There is great diversity in the appearance of fluid collections on computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and ultrasound.

- Physical properties that interact with imaging parameters producing the diversity of these appearances is important to understand.

- Many cysts that are seen are clinically insignificant.

- Ultrasound is usually not definitive for diagnostic imaging purposes in evaluating cystic neck masses except for thyroid masses.

Tumor, infection, trauma (with or without bleeding and iatrogenic or by other mechanisms), and aberrant development (Chapter 8) can all be associated with cysts, localized fluid collections, and hematomas. Edema confined to a space can mimic a fluid collection.

Cysts, fluid collections, and bleeding occur very commonly in the sinuses. They are also common occurrences in the soft tissues and organ systems of the head and neck. They occur both within bone and beneath the periosteum. There are cysts associated with tumor and regressive cystic changes and bleeding within tumors or tumoral cysts and cystic tumors. Developmental cysts are common in the head and neck, and some, such as venolymphatic vascular malformations (Chapter 9), have bleeding as a complication.

GENERAL DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH

The general diagnostic approach to the evaluation of cysts, fluid collections, and hematomas or other collections of blood products includes consideration of one or more of the following topics.

Clinical Setting

The clinical setting virtually always guides the differential diagnosis. The origin and nature of a cyst, hematoma, or other fluid collection is usually not in question after imaging is combined with clinical data. Sampling by aspiration of fluid contents is usually not necessary unless cancer or infection is suspected. A partial list of some examples of common associated clinical circumstances follows:

- A history or acute setting of trauma raises the possibility of hematoma or posttraumatic hematocyst (Fig. 10.1).

FIGURE 10.1. Non–contrast-enhanced computed tomography showing the density of the acute hematoma contributing to the airway obstruction in this trauma patient to be greater than that of muscle.

- A rapid increase in size suggests bleeding or bleeding into a pre-existing lesion. (Fig. 10.2)

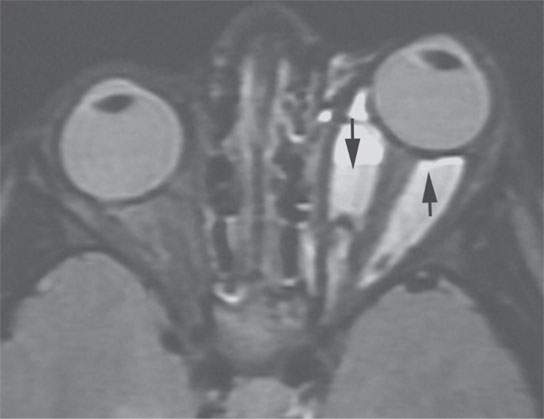

FIGURE 10.2. Short T1 inversion recovery (STIR) magnetic resonance image of a patient who presented with acute enlargement of an orbital mass. Fluid–fluid levels (arrows) are likely related to blood products.

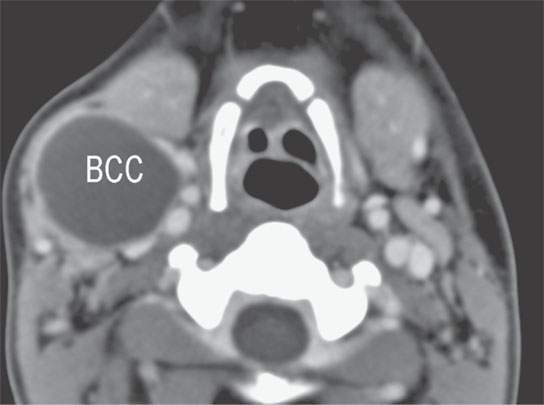

- A history of fluctuating size suggests a developmental lesion that may be liable to intermittent inflammation, one that may contain tissue responsive to inflammation, or one that communicates with the outside world somehow by a tract or fistula (Fig. 10.3).1,2

FIGURE 10.3. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of a second branchial cleft cyst (BCC) with a smooth thin wall and no surrounding inflammatory changes.

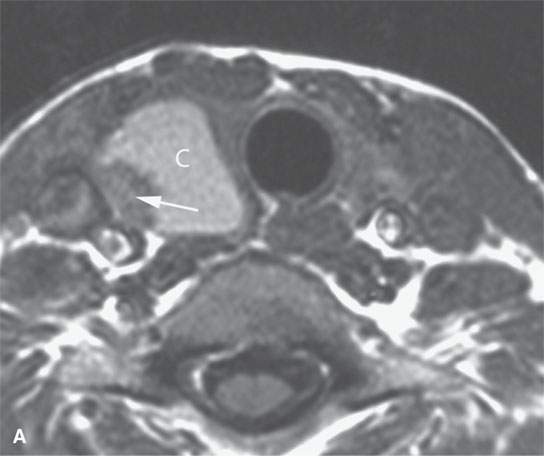

- Steady progressive enlargement over a protracted period of time without pain or signs of inflammation suggests a neoplasm (Fig. 10.4).1–3

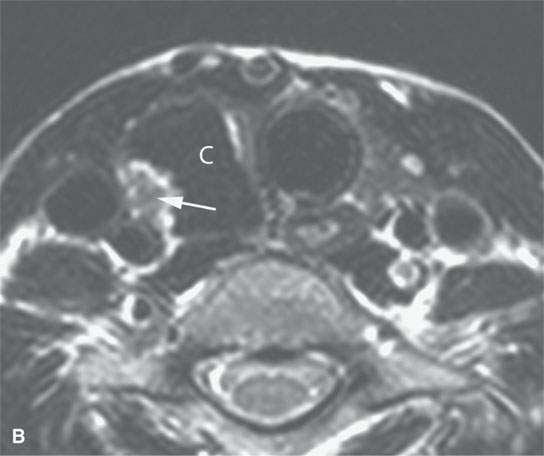

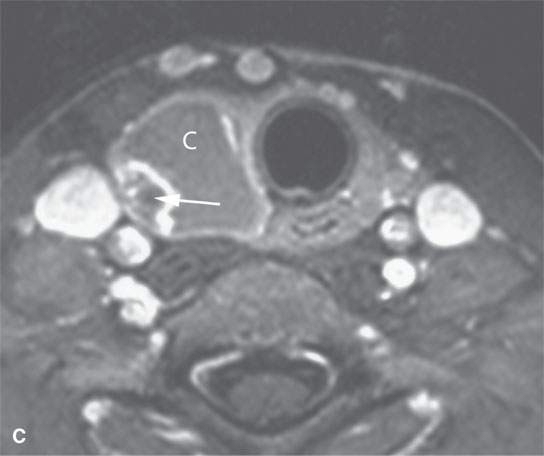

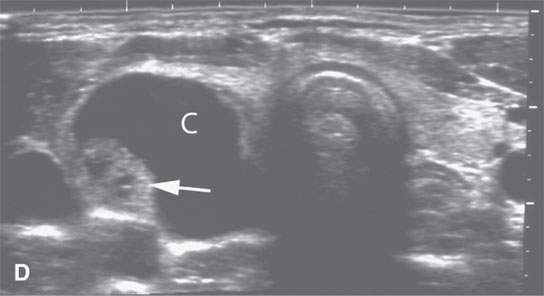

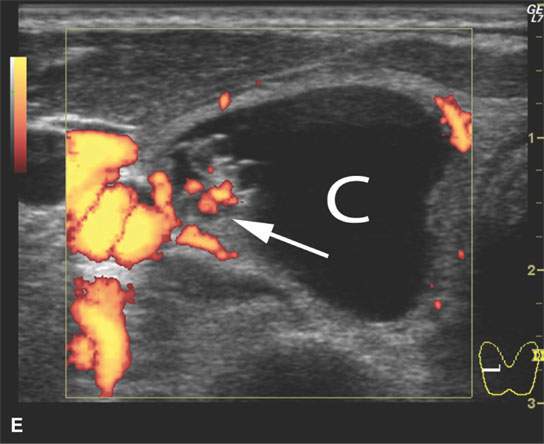

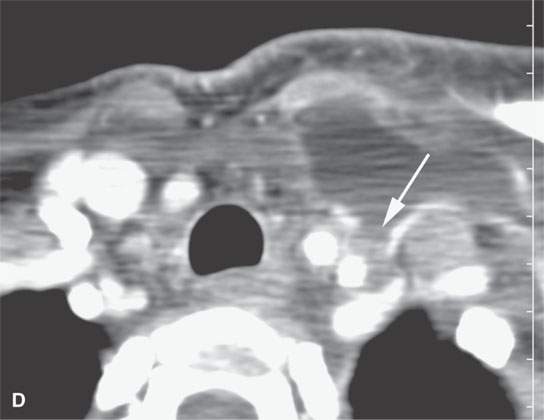

FIGURE 10.4. Patient with an enlarging low neck mass imaged first with ultrasound and then magnetic resonance imaging showing a cyst (C) and associated nodule in all of the following images. A: T1-weighted non–contrast-enhanced image showing a high signal intensity cyst suggesting that it contains colloid or blood products associated with a nodule (arrow). B: T2- weighted image shows the cyst to be of very low signal intensity suggesting the presence of blood products or desiccated colloid, but fibrosis or calcification would not seem to be reasonable alternative explanations based on all of the imaging findings. C: T1- weighted fat-suppressed contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance image shows that the cyst wall does not enhance and that the nodule is irregular and obviously vascularized. D: Comparison transverse B-mode ultrasound. E: Color flow ultrasound image shows that the nodule is not only irregular but also well vascularized.

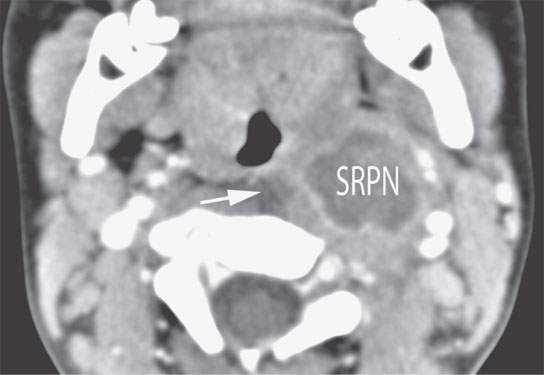

- Fever, poor feeding, and pharyngitis with retropharyngeal edema in a young child suggest a suppurative retropharyngeal lymph node (Fig. 10.5).

FIGURE 10.5. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography in a 1-year-old child with partially treated suppurative retropharyngeal adenitis. The suppurative node (SRN) has a minimally enhancing margin and relatively low grade surrounding inflammatory response and a small amount of retropharyngeal edema (arrow).

Normal Variant and Common, or Incidental and Unimportant

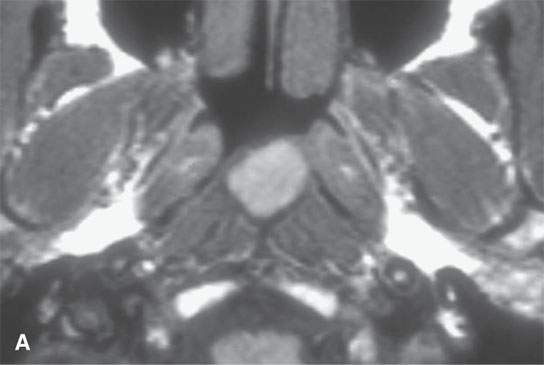

Cysts or fluid collections are often anatomic variations such as the Tornwaldt cyst of the nasopharynx (Fig. 10.6).4 Cysts or fluid collections may also be totally innocuous, such as the very common postinflammatory cysts in the Waldeyer ring lymphoid tissue (Fig. 10.7) or simple mucous or retention cysts in the sinuses.1–3 Such variants should be recognized as unimportant clinically, but they do allow a study of the appearance of cyst contents in a way that might prove helpful in understanding cysts and fluid collections that do have some consequence.

FIGURE 10.6. Magnetic resonance imaging of an incidental Tornwaldt’s cyst. A: T1-weighted image shows high signal intensity almost approaching that of fat. B: T2-weighted image shows the cyst contents to be much less intense than cerebrospinal fluid, likely related to the mucoid nature of those cyst contents.

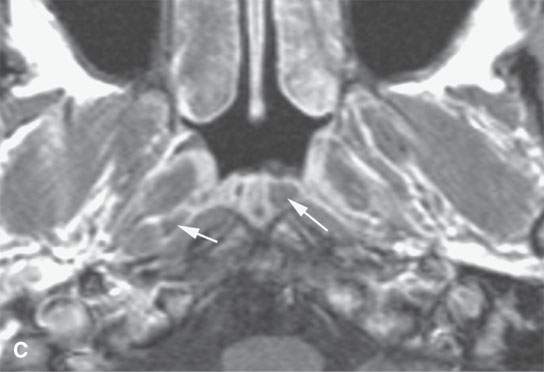

FIGURE 10.7. Magnetic resonance imaging of incidental and clinically insignificant retention or postinflammatory cysts in the adenoids. A: On T1-weighted images, the cysts are isointense to the normal lymphoid tissue. B: On T2-weighted images, the cysts become far more conspicuous (arrows). C: Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted images shows the cysts differentiated from the normally enhancing lymphoid tissue (arrows).

Solitary or Multiple Cysts

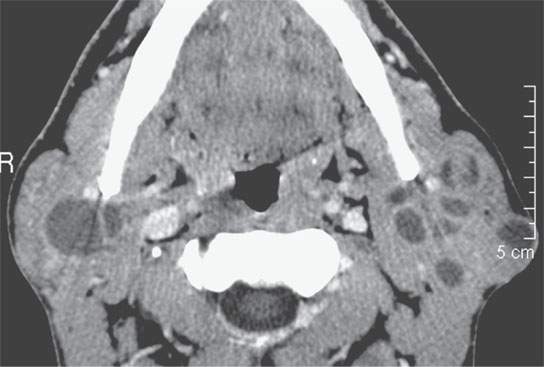

If cysts or cystic masses are multiple, and especially if they are multiple and bilateral, they can suggest systemic diseases as diverse as basal cell nevus syndrome and HIV infection, depending on their anatomic distribution (Fig. 10.8). One the other hand, unilateral multiple parotid and periparotid cystic masses suggest a Warthin tumor or metastatic skin cancer to regional parotid nodes.

FIGURE 10.8. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of an HIV patient with bilateral lymphoepithelial cysts.

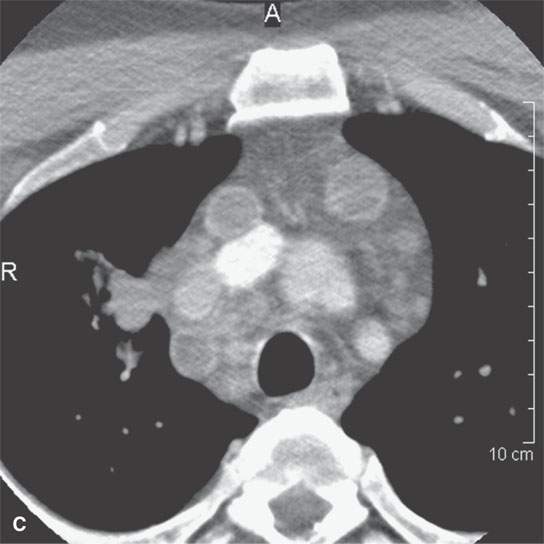

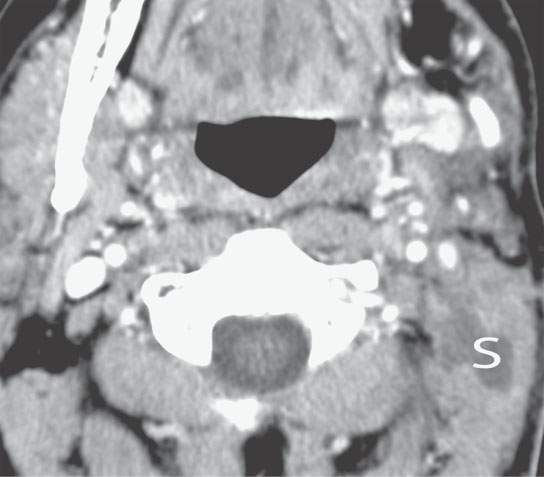

Multiple cystic lesions in the neck raise the possibility of lymphadenopathy.1–3 The pattern of disease and clinical situation usually clarify the likely etiology to no more than two choices (Fig. 10.9).

FIGURE 10.9. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of an HIV-positive patient with bilateral neck masses. A–C: Multiple, bilateral cystic masses and obviously mediastinal adenopathy. The walls of the nodes enhance minimally, and there is a relatively low grade inflammatory response surrounding the nodes in both the neck and the mediastinum.

Anatomic Relationships

Decisions about whether a predominantly cystic mass is a nodal versus nonnodal etiology is largely driven by anatomy.

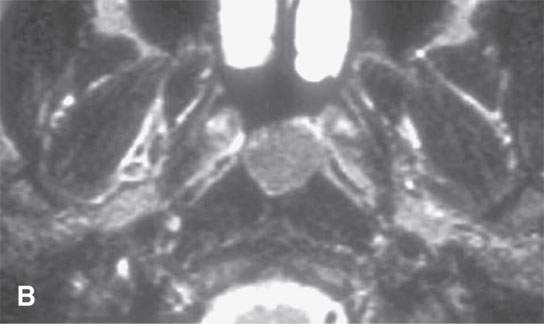

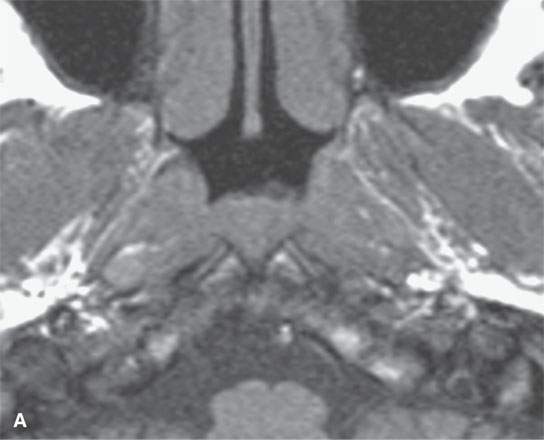

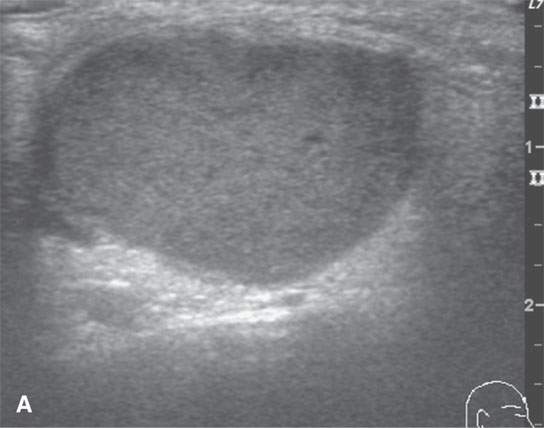

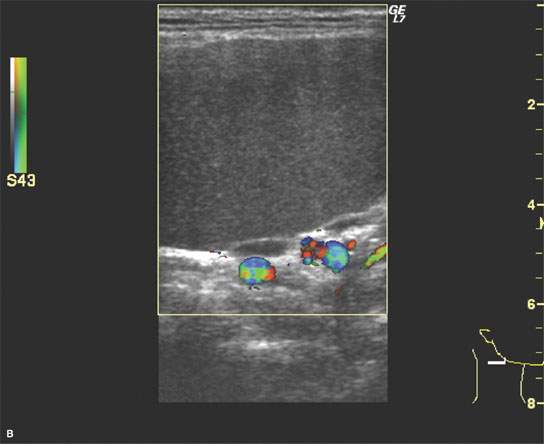

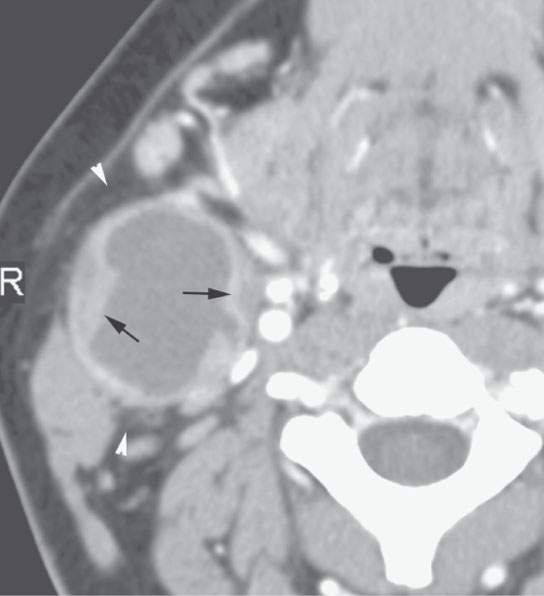

Developmental cysts such as those of the branchial apparatus (Figs. 10.10, 10.11 and 10.12) and thyroglossal duct (Figs. 10.13 and 10.14) often bear a characteristic relationship to the pharynx and other neck viscera, but some ambiguity in a purely anatomic differentiation arises in differentiation of second branchial cleft cysts and necrotic or otherwise cystic level 2A lymph nodes (Fig. 10.11).5–7

FIGURE 10.10. Ultrasound of a right-sided neck mass subsequently proven to be a second branchial cleft cyst. The color flow images showed displaced vessels and confirmed that the mass itself was not vascular. The ultrasound was only marginally useful in the diagnostic process for these purposes.

FIGURE 10.11. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of a second branchial cleft cyst with a thick nodular wall (arrows) and relatively low grade inflammatory changes in the surrounding fat (arrowheads).

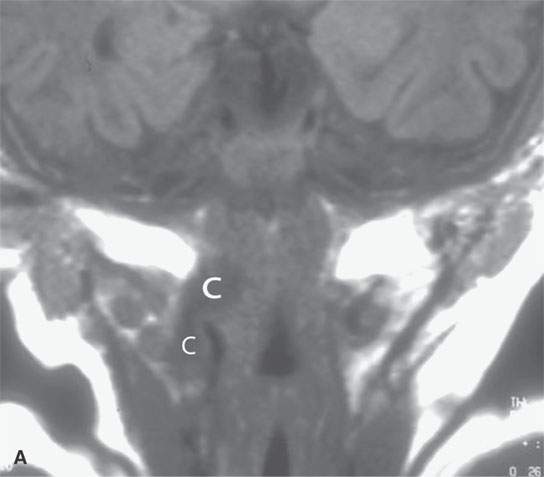

FIGURE 10.12. Magnetic resonance imaging of an infant with a pharyngeal wall mass. In both the T-weighted (A) and T2-weighted (B) images, the cystic structure (C) can be seen. Its appearance as it crosses the muscular (M) pharyngeal wall (arrow) to extend from the pharynx into the neck is an anatomic pattern unmistakably recognizable as a branchial apparatus anomaly, even though this particular type of cyst is rare.

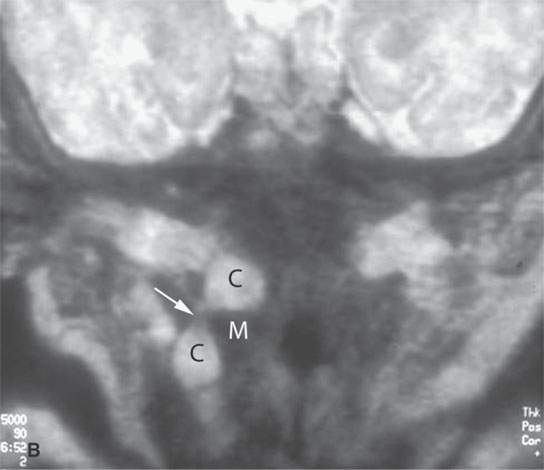

FIGURE 10.13. Ultrasound of a pediatric patient believed to have a thyroglossal duct cyst. The study showed a cyst and a nodule but was not anatomically complete enough to confirm the diagnosis of a thyroglossal duct cyst. In essence, these were resources and time that might have been better spent.

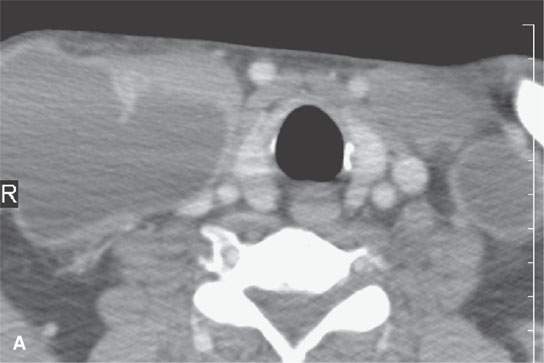

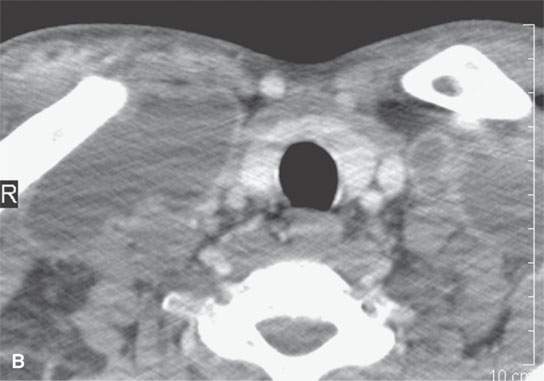

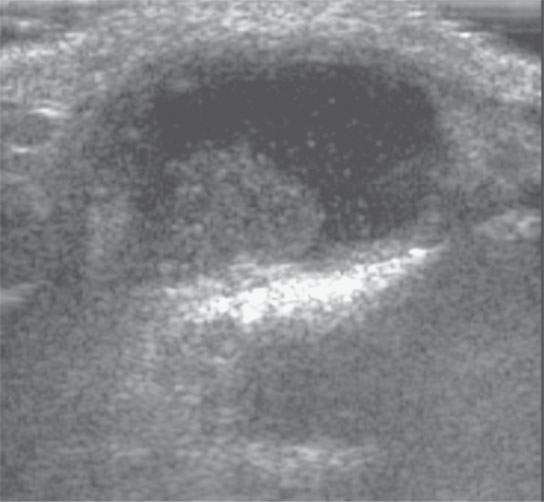

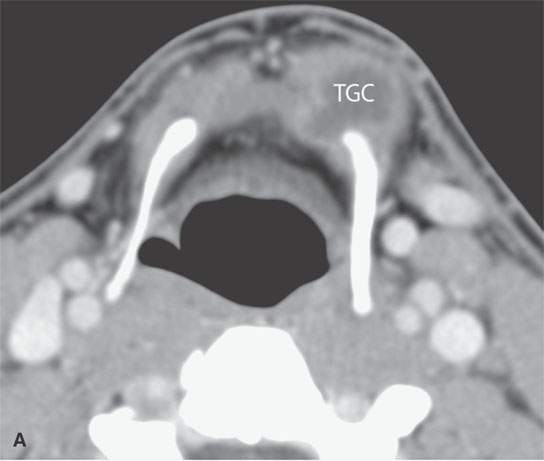

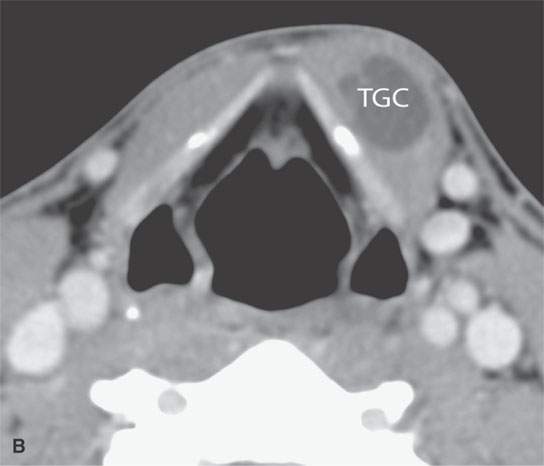

FIGURE 10.14. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of a patient suspect of having a thyroglossal duct cyst. The study, two images from which are seen in (A) and (B), confirmed the diagnosis and the full extent of the thyroglossal duct cyst (TGC), allowing for proper surgical planning of a modified Sistrunk procedure.

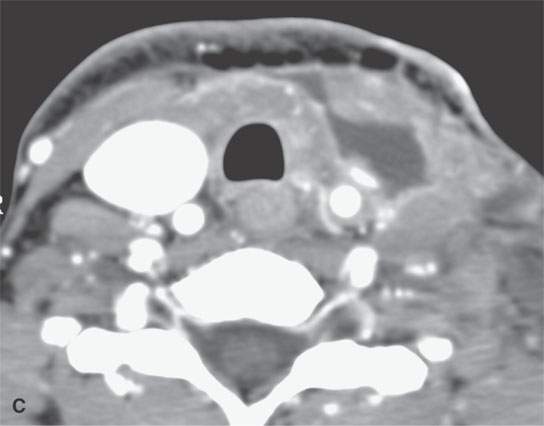

The sinonasal region, salivary glands, thyroid gland, and all other viscera have a tendency to be associated with certain types of cysts, fluid collections, and patterns of bleeding. For instance, serous and mucous retention cysts will be submucosal within the sinus cavity, and HIV-related epithelial cysts will be partially solid and usually bilateral in the parotid and sometimes submandibular glands (Fig. 10.8). Colloid cysts and cystic adenomas of the thyroid gland are ubiquitous, and some predominantly cystic masses may be thyroid cancer (Fig. 10.15).

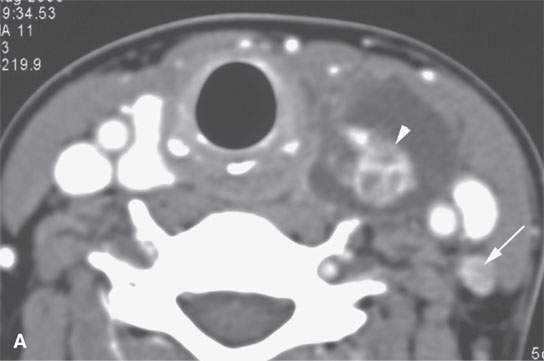

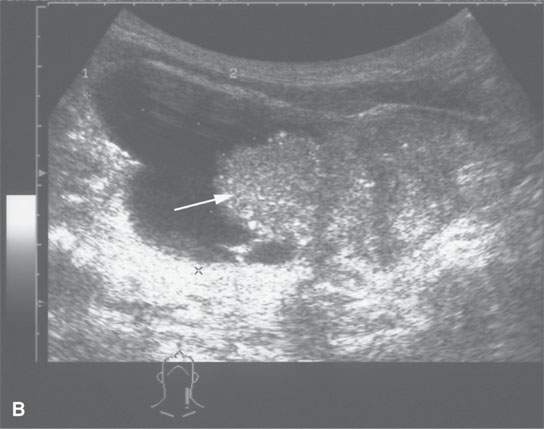

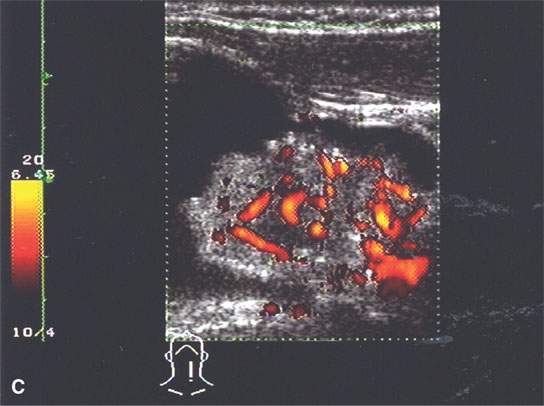

FIGURE 10.15. Patient with an enlarging low neck mass imaged first with ultrasound and then contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) showing a cyst and associated nodule in all of the following images. A: CECT image showing an irregular nodule with a cyst that shows calcification, possibly psammomatous, and an enhancing metastatic level 4 lymph node (arrow). B: Ultrasound showing an irregular nodule and some shadowing suggestive of psammomatous calcification. E: Color flow image shows that the nodule is not only irregular but also well vascularized.

Edema confined to a known anatomic space such as the retropharyngeal space may mimic a fluid collection.

Postoperative fluid collections in the low neck and supraclavicular fossa may be related to injury to the thoracic duct or other major lymphatic collecting trunks in this region (Fig. 10.16). Postoperative seromas typically accumulate in the anterior and/or posterior triangles and deep to the closure of the superficial fascia or deeper fascial layers of the neck after a surgical procedure, the most common being a neck dissection (Figs. 10.17–10.20).

FIGURE 10.16. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the normal thoracic duct. A: Fluid density structure with no visible wall (arrow) is another example of a consistently visible normal cystic structure that is visible on modern imaging studies. B: Oblique reformations show the thoracic duct (arrow) near its connection to the subclavian vein.

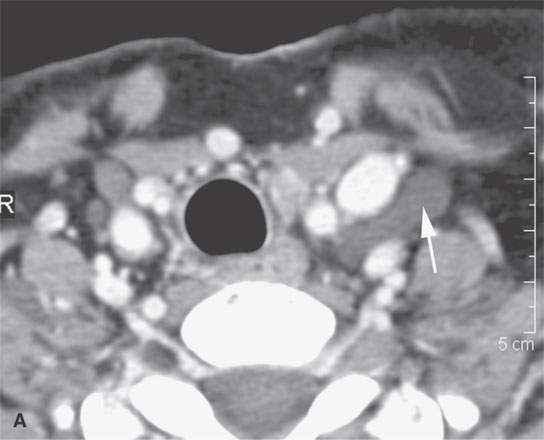

FIGURE 10.17. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography show a small seroma (S) in the posterior triangle with no enhancement at its margins.

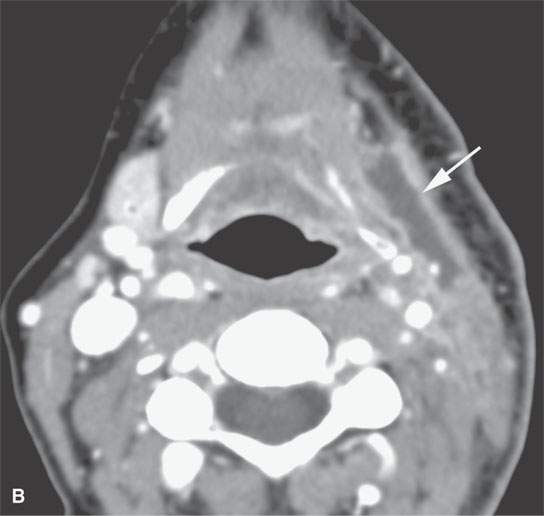

FIGURE 10.18. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography showing a postoperative seroma and chyle leak. Some areas of the fluid collection show reactive enhancement along its margins (arrow in A) while others do not (arrowhead in A). A, B: The collection lies deep to the closure of the superficial fascia (arrows) and around the carotid sheath and in the posterior triangle. C, D: The collection is mainly deep to the investing layer of cervical fascia and then projects into the region where the thoracic duct joins the subclavian vein (arrow) suggestive of a chyle leak, explaining at least part of the fluid collection.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree