Etiology

Fungal infections of the chest can be divided into two groups based on pathogenesis. The first group is composed of endemic fungi, including Histoplasma capsulatum, Coccidioides immitis, Blastomyces dermatitidis, and Cryptococcus gattii , and the second group is composed of opportunistic fungi, including Aspergillus, Candida, Cryptococcus neoformans, and Zygomycetes.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

The endemic fungi typically reside in the soil of certain regions, which is discussed in more detail in subsequent subsections. Infection primarily occurs when an otherwise healthy individual lives in or visits an endemic area and inhales microconidia (spores) of the fungus. In contrast, opportunistic fungi are ubiquitous and are found worldwide. These fungi tend to infect individuals with underlying lung disease or suppressed immune systems.

Clinical Presentation

In most individuals respiratory infection with endemic fungi is mild or subclinical and self-limited. In a few patients the infection is more severe, may disseminate, and can be fatal. Infection tends to be more severe after heavy microconidial exposure. The infection may manifest after the patient has left the endemic area, so clinical familiarity with the disease is important even outside the endemic regions.

Opportunistic fungal infections, especially Aspergillus infection, have a variety of clinical manifestations that will be described in detail. Immunocompromised individuals and individuals with underlying lung disease are at increased risk of more serious disease with either endemic or opportunistic fungal infections.

Pathophysiology

Pathology

Immunocompetent patients with endemic fungal chest infection most often develop bronchopneumonia with regional lymph node involvement. These patients rarely progress to chronic forms of the disease or dissemination. Patients with underlying lung disease or immunocompromised patients are at risk for more serious forms of infection, such as dissemination, chronic infection, angioinvasion, or extension into the pleura or chest wall. Asthmatics may develop a hypersensitivity reaction to Aspergillus infection, resulting in dilated segmental and proximal subsegmental bronchi that often contain mucus plugs.

Manifestations of the Disease

Histoplasmosis

Acute Histoplasmosis

General.

Histoplasmosis is caused by inhalation of the microconidia of the dimorphic fungus H. capsulatum. Endemic regions include central and eastern North America, especially in the Ohio, Mississippi, and St. Lawrence River valleys. Bird and bat droppings enhance its growth by accelerating sporulation. More than half of adults living in endemic areas have been infected with H. capsulatum. Acute histoplasmosis may be asymptomatic or may result in a flu-like illness, including a fever, dry cough, and fatigue. The severity of the illness may vary with level of exposure or immune status or both.

Radiography.

The chest radiograph in most patients is normal. In asymptomatic individuals the most common finding is a solitary pulmonary nodule of variable size. Nodules in asymptomatic individuals may enlarge, may be multiple, and are often associated with lymphadenopathy. Nodule cavitation is rare. Symptomatic patients most commonly show single or multiple areas of patchy airspace consolidation with a lower lung predominance ( Fig. 12.1 ). Mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy is common and may be the only finding. Pleural effusions are rare. More severe cases, such as cases occurring after heavy exposure, may show multiple small nodules or patchy airspace consolidation in both lungs (see Fig. 12.1 ). The former may resemble metastatic disease. Airspace consolidation may form a nodule while clearing.

A nodule may persist despite resolution of the acute infection. It may subsequently calcify, forming a calcified granuloma. Infected lymph nodes also may calcify ( Fig. 12.2 ). The presence of central, laminar, or diffuse calcification within a nodule, calcification within an associated lymph node, or both helps identify a nodule as a calcified granuloma. This also helps to distinguish a nodule from a primary lung cancer.

Computed Tomography.

Computed tomography (CT) may reveal unilateral or bilateral nodules or areas of consolidation and lymphadenopathy that often mimic primary lung cancer (see Fig. 12.1 ). Satellite nodules and centrilobular nodules (sometimes with a tree-in-bud pattern) also may be seen. As the findings of acute histoplasmosis resolve, a nodule may persist and develop central, laminated, or diffuse calcification (see Fig. 12.2 ). CT without intravenous (IV) contrast administration is helpful to detect these benign patterns of calcification and identify them as a calcified granuloma, with histoplasmosis being one possible cause. CT without IV contrast administration also improves detection of calcification of associated lymph nodes. Calcified granulomas also may be seen in the liver and spleen.

Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography.

In general, infection may have increased glucose metabolism and cause a false-positive positron emission tomography (PET)/CT scan. This may be a confounding factor when PET/CT is used in the workup of histoplasmosis or any fungal infection.

Imaging Algorithms.

Initially, the patient would likely have a posteroanterior and lateral chest radiograph. A routine chest CT would not typically be obtained unless there was clinical uncertainty about the diagnosis (i.e., concern for malignancy) or if the patient’s clinical course was not progressing as expected. CT without IV contrast administration is suggested because it helps detect and characterize calcification in nodules and lymph nodes.

- •

Normal chest radiograph

- •

Solitary or multiple nodules

- •

Single or patchy areas of airspace consolidation

- •

Mediastinal or hilar lymphadenopathy

- •

Possible satellite nodules on CT

- •

Nodules and lymphadenopathy often calcify with time

Chronic Histoplasmosis

General.

Chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis is rare and occurs almost exclusively in middle-aged men with emphysema. The infection can mimic post–primary tuberculosis, but symptoms are not as severe, and the course is usually self-limited and nonfatal. Pathogenesis is thought to be caused by spore inhalation into upper lobe bullae resulting in fluid formation within the bullae. The antigen-filled fluid may spread via spillage into the bronchial tree, resulting in pneumonitis in other areas of the lungs. Symptoms include productive cough, fever, dyspnea, fatigue, weight loss, and hemoptysis.

Radiography.

Radiographs show unilateral or bilateral upper lobe airspace opacities that usually extend to the pleura. There are usually changes of emphysema. If a bulla is surrounded by airspace opacity, it may resemble a cavitary lesion, mimicking tuberculosis. The “cavity” may develop wall thickening, change size, or develop an air-fluid level. The thickness of the wall roughly reflects the activity level of the infection. There may be adjacent pleural thickening. Adjacent lung parenchyma may be destroyed as the cavity enlarges. The cavity may become secondarily infected by an aspergilloma (see subsequent section). In contrast to acute histoplasmosis, lymphadenopathy is usually absent.

Computed Tomography.

CT may be used to show the aforementioned radiographic findings in more detail.

Imaging Algorithms.

Chronic histoplasmosis would likely be imaged using a chest radiograph, followed by chest CT for further evaluation. Either modality could be used to follow the response to treatment.

- •

Unilateral or bilateral upper lobe airspace opacities with emphysema

- •

Bulla with surrounding airspace opacity, mimicking a cavitary lesion

- •

No lymphadenopathy

Histoplasmoma

General.

When a nodule resulting from histoplasmosis slowly enlarges over time, it is referred to as a histoplasmoma. Histologic sections show that a histoplasmoma is a small necrotic focus surrounded by a massive fibrous capsule. Increasing fibrosis at the periphery of the lesion results in its growth. Histoplasmomas are typically asymptomatic.

Radiography.

The most common finding is a discrete nodule measuring less than 30 mm in diameter that is most often located peripherally and in a lower lobe. The nodule may be uncalcified or may have central, diffuse, or laminated calcification. In one study, the growth rate varied from 0.5 to 2.8 mm per year, averaging 1.7 mm per year. Satellite nodules and calcified hilar lymph nodes are common.

Computed Tomography.

CT without IV contrast administration is more sensitive than radiographs in detecting benign patterns of calcification and can help distinguish a histoplasmoma from a bronchogenic carcinoma. Growth rates can be measured more accurately on CT, which may be helpful because histoplasmomas tend to grow more slowly than typical bronchogenic carcinomas ( Fig. 12.3 ).

Imaging Algorithms.

Histoplasmomas likely would be detected first as a nodule on a chest radiograph. A thin-section chest CT scan without IV contrast administration would be helpful to detect and characterize possible internal calcification. Follow-up using unenhanced CT would be helpful to assess for change in calcification or size over time.

- •

Discrete nodule enlarging slowly over time

- •

May have central, diffuse, or laminated calcification

- •

Associated satellite nodules or calcified lymphadenopathy

Disseminated Histoplasmosis

General.

Disseminated histoplasmosis, a rare form of histoplasmosis infection, is an opportunistic infection that affects immunocompromised individuals, such as organ transplant recipients or acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) patients, infants, or adults older than 54 years, especially men. Human immunodeficiency virus-1 infection is a major risk factor. Dissemination may result from progression of a primary infection or from reactivation of a prior infection. Severely immunocompromised patients and infants may present with respiratory distress, hepatic and renal failure, shock, and coagulopathy and are at risk of a rapidly fatal course. Other patients experience chronic progressive symptoms of fever, cough, weight loss, dyspnea, night sweats, and fatigue. Decreased mental status and headaches occur in 40% of patients.

Radiography.

Chest radiographs may be normal. Normal chest radiographs occur in approximately 50% of AIDS patients compared with 30% of patients with immunodeficiency from other causes. When abnormal, radiographs most commonly show multiple diffuse bilateral nodules, usually measuring 3 mm in size ( Fig. 12.4 ). The second most common finding is the presence of linear or irregular opacities, which are often diffuse. Nodules or linear opacities may progress to diffuse airspace disease. Focal airspace opacities occur in approximately 10% of cases. Lymphadenopathy and pleural effusions are uncommon.

Computed Tomography.

Miliary nodules may be seen on CT, measuring 1 to 3 mm in diameter with poorly or sharply defined margins (see Fig. 12.4 ). The nodules are randomly distributed and can be seen along interlobular septa, vessels, and fissures and within the secondary pulmonary lobule. There is frequently mild hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy.

Imaging Algorithms.

Chest radiographs may be obtained initially, but thin-section chest CT without IV contrast would be more sensitive to detect disease.

- •

Chest radiograph may be normal

- •

Multiple diffuse bilateral 1- to 3-mm nodules that may progress to airspace disease

Mediastinal Granuloma and Fibrosing Mediastinitis

General.

As a sequela to histoplasmosis infection, a chronic fibrotic process may develop in the mediastinum either diffusely (fibrosing mediastinitis) or locally (mediastinal granuloma). The latter process is more common and is composed of enlarged lymph nodes that have become matted together and surrounded by a fibrous capsule. Mediastinal granuloma or fibrosis may lead to obstruction of the superior vena cava, pulmonary vessels, central airways, or esophagus.

Radiography.

Chest radiographs may show mediastinal widening (from the granuloma or distended collateral vessels or both), atelectasis or consolidation (from central airway obstruction), signs of pulmonary infarct (from vascular obstruction), or nodal calcification.

Computed Tomography.

CT is essential to reveal the specific details of mediastinal fibrosis or granuloma. The most common finding is a localized calcified mediastinal or hilar soft tissue mass, which in the appropriate clinical setting is highly suggestive of histoplasmosis-induced fibrosing granuloma or mediastinitis ( Fig. 12.5 ). There may be associated lymph nodes that may be calcified. With IV contrast, CT can demonstrate vascular involvement, including superior vena cava obstruction and pulmonary venous or arterial narrowing (see Fig. 12.5 ). Tracheal and/or bronchial narrowing may also be seen, depending on the location and extent of involvement.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be used to show a mediastinal or hilar mass and vascular narrowing or obstruction. There is typically a heterogeneous, infiltrating mass of intermediate signal intensity on T1-weighted images and variable signal intensity on T2-weighted images. Fibrosis and calcification are typically responsible for decreased signal intensity on T2-weighted images, whereas areas of active inflammation can cause increased T2 signal intensity. The presence of decreased signal intensity within a mediastinal mass on MRI may help distinguish it from neoplasm. MRI may be an alternative to CT in patients who cannot receive IV CT contrast agents.

Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography.

Fibrosing mediastinitis or mediastinal granuloma may cause a false-positive PET/CT scan, and this modality is not routinely used for evaluation of this condition.

Imaging Algorithms.

Routine chest CT without and with IV contrast administration is helpful to detect and define the fibrosis or granuloma, associated calcifications, and vascular or central airway narrowing. In cases of esophageal involvement, an esophagogram may be helpful to evaluate motility and patency and to detect possible traction diverticula.

- •

Widened mediastinum on chest radiograph

- •

Mediastinal or hilar soft tissue mass with calcifications

- •

Secondary narrowing of airways, superior vena cava, pulmonary vessels, or esophagus

Broncholithiasis

General.

A calcified peribronchial lymph node caused by histoplasmosis occasionally may erode into an airway, causing broncholithiasis. Symptoms most commonly include a nonproductive cough and hemoptysis. Less commonly, patients may have fever, chills, and pain from post–obstructive pneumonitis. Expectoration of a broncholith (lithoptysis) also may occur.

Radiography.

The calcified lymph node may be seen on chest radiograph and may be associated with post–obstructive atelectasis, pneumonitis, or bronchiectasis. However, it may be difficult to see that the calcified lymph node is endoluminal.

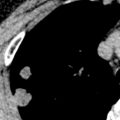

Computed Tomography.

Broncholithiasis may be diagnosed on CT as a calcified endobronchial or peribronchial nodule that has associated signs of obstruction, such as atelectasis, pneumonitis, and bronchiectasis ( Fig. 12.6 ). Unenhanced CT, using thin collimation and multiplanar reconstruction, may be necessary to localize the broncholith accurately within the lumen and may aid bronchoscopic removal.

Imaging Algorithms.

Routine chest CT is recommended without IV contrast administration. Thin-section imaging and multiplanar reconstruction may be necessary to localize the broncholith. Virtual bronchoscopy may aid in bronchoscopic removal.

- •

Calcified nodule in a bronchus

- •

Signs of prior granulomatous infection

- •

Post–obstructive atelectasis or consolidation or both

Coccidioidomycosis

Coccidioidomycosis (San Joaquin Valley fever) is caused by the dimorphic fungus C. immitis. This fungus is found in soil and is endemic in the southwestern United States, northern Mexico, and, to a lesser degree, regions of Central and South America. Specific endemic areas of the United States include south-central Arizona, southern California (notably the San Joaquin Valley), western Texas, and parts of New Mexico. The incidence of pulmonary coccidioidomycosis is highest in the late summer and early fall, when the soil is driest. Infection is caused by inhalation of the fungal arthrospores or arthroconidia.

Primary Coccidioidomycosis or Acute Pulmonary Coccidioidomycosis

General.

Similar to histoplasmosis, most cases of primary coccidioidomycosis are asymptomatic or mild, although symptoms occur more frequently than in histoplasmosis. Symptoms typically develop 1 to 4 weeks after exposure and comprise flu-like symptoms such as cough, fever, chest pain, fatigue, anorexia, and headache. Skin rashes also may occur. The most common skin rash is a diffuse erythematous rash called toxic erythema, occurring in 10% to 30% of patients. Approximately 5% of patients develop erythema nodosum or erythema multiforme. These rashes may be associated with arthralgias and mild conjunctivitis, termed Valley fever complex. The infection is usually self-limited, resolving over 3 to 6 weeks.

Radiography.

Various nonspecific findings are observed on chest radiographs. The most common finding consists of single or multiple foci of airspace consolidation. Single or multiple nodules also may occur, which may cavitate and develop air-fluid levels. Hilar or mediastinal lymphadenopathy occurs in approximately 20% of cases, usually in association with lung parenchymal findings ( Fig. 12.7 ). Pleural effusions, most commonly small, may occur in 10% to 20% of patients as a result of contiguous spread from a subpleural focus. Radiographic findings usually resolve completely. Endobronchial or endotracheal involvement is rare.

Computed Tomography.

Chest CT may be used to show the morphology of small pulmonary lesions that are poorly seen on chest radiography. Nodules (see Fig. 12.7 ) or consolidation may be seen. There may be associated satellite nodules ( Fig. 12.8 ).

Imaging Algorithms.

Chest radiographs are most commonly obtained. Chest CT may be helpful if the diagnosis is uncertain, or if the patient does not improve as expected or develops a complication. Chest CT also may show satellite nodules not apparent on the radiograph.

- •

Single or multiple foci of consolidation or nodules

- •

May cavitate

- •

May have satellite nodules on CT

Chronic or Persistent Pulmonary Coccidioidomycosis

General.

Approximately 5% of cases of primary coccidioidomycosis become chronic. The infection commonly continues to be asymptomatic or mild but may develop into a severe pneumonia with fever, productive cough, night sweats, and hemoptysis.

Radiography.

The most common radiographic finding is cavitation, which is usually thin-walled, solitary, and in the upper lobes and is said to resemble a grape skin ( Fig. 12.9 ). Cavitations may become secondarily infected or may rupture into the pleural space and may cause pleural effusion, empyema, or pneumothorax. Another radiographic finding consists of single or, less commonly, multiple pulmonary nodules. Nodules or masses are 5 to 50 mm in diameter and are usually peripheral. These can be difficult to distinguish from bronchogenic carcinoma or metastatic disease.

Computed Tomography.

A retrospective analysis of 18 patients with chronic coccidioidomycosis showed that the most common CT finding was a solitary nodule measuring 10 to 20 mm in diameter in the periphery of the lungs. Focal areas of ground-glass opacity and consolidation were less common. Nodules were most commonly homogeneous in attenuation, but central low attenuation, cavitation, or calcification also occurred (see Fig. 12.9 ). A few of these nodules had surrounding ground-glass opacity (CT halo sign), likely resulting from granulomatous inflammation or hemorrhage.

Imaging Algorithms.

Chest radiographs are routinely obtained, but chest CT is more sensitive in depicting the findings and complications of chronic coccidioidomycosis.

- •

Solitary nodule or cavitation, usually thin-walled (grape skin sign)

- •

Upper lobe, peripheral

North American Blastomycosis

General

North American blastomycosis is caused by the inhalation of asexually produced spores or conidia of the thermally dimorphic fungus Blastomyces dermatitidis. The disease has endemic regions in Africa, Central America, and South America, but it is most common in North America. In North America endemic areas include the south-central and southeastern United States along the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys, midwestern states and Canadian provinces along the Great Lakes, and a small area in New York and Canada along the St. Lawrence River. The fungus proliferates in the warm, moist soil of wooded areas rich in organic debris.

Similar to histoplasmosis and coccidioidomycosis, blastomycosis may be asymptomatic or cause mild flu-like symptoms. More commonly, it manifests as acute pneumonia with fever, productive cough, pleuritic chest pain, arthralgias, and myalgias. Diagnosis is often delayed because its clinical and radiographic findings are nonspecific and variable and often mimic more common diseases. Cutaneous lesions may occur and improve diagnostic accuracy. These include a verrucous lesion with a raised, irregular border with crusting and drainage or an ulcerative lesion with a sharp, heaped-up border and exudate at its base.

Radiography

Radiographic findings are varied and nonspecific and include consolidation, masses, nodules, cavitation, and interstitial changes. There is often an upper lobe predominance. Findings often resemble community-acquired pneumonia, but granulomatous infection should be suspected if the findings progress or are slow to resolve. The most common appearance is patchy or confluent airspace consolidation, which often has ill-defined margins and air bronchograms and is more commonly segmental or subsegmental than lobar. The second most common appearance is a pulmonary mass or masses, which are typically well circumscribed, with smooth or irregular margins and 3 to 10 cm in diameter. These may be confused with bronchogenic carcinoma. Cavitation occurs in 11% to 37% of cases. Interstitial changes, usually diffuse and bilateral, and nodules are less common. Lymphadenopathy is uncommon. Pleural effusions, usually very small, may occur in 21% of cases. Pleural thickening without pleural effusion may occur. Rarely, blastomycosis may aggressively cross tissue planes to cause pleural effusions, is chest wall masses, rib erosions, and cutaneous fistulae.

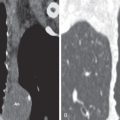

Computed Tomography

In a study of CT findings in 16 patients with pulmonary blastomycosis, the most common finding was pulmonary masses (88%), which frequently contained air bronchograms. Other common findings included nodules less than 2 cm in diameter (75%), perihilar location of parenchymal disease (75%), satellite lesions (69%), and consolidation (56%) ( Figs. 12.10 and 12.11 ). Less common findings included lymphadenopathy (25%), pleural thickening (25%), pleural effusion (13%), and cavitation (13%). Parenchymal findings or lymphadenopathy is occasionally calcified (25% and 44%, respectively).