Fig. 6.1

Normal gallbladder shaped as a Phrygian cap

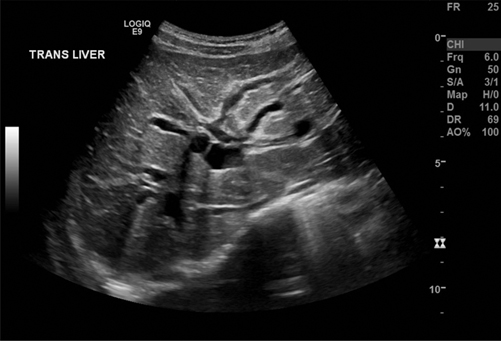

Next, the cystic and common bile ducts (CBD) are identified, which runs parallel to the portal vein as an anechoic tube with hyperechoic borders. Intrahepatic ductal dilatation is indicative of distal obstruction (Fig. 6.2). Color Doppler aids in differentiation of vascular structures and extra- and intrahepatic bile system. When dilated in the setting of choledocholithiasis , pancreatitis or type 1 choledochal cyst , the common bile duct can be easily followed into the pancreatic head and to the duodenum with the ultrasound probe. The size of the CBD is age-dependent; in adults, the upper limit of 6 mm is frequently used, but a study of healthy pediatric patients less than 13 years of age found that all had a CBD size less than 3.3 mm, and children less than 3 months had a CBD size less than 1.2 mm [3]. After cholecystectomy, the bile duct tends to enlarge by a few millimeters.

Fig. 6.2

Intrahepatic biliary ductal dilatation as a sign of distal bile duct obstruction

The intrahepatic bile system is examined as part of the liver scan. The fine ducts follow the intrahepatic arterial system and may be differentiated by color Doppler. When not dilated, the ducts are hard to follow into the periphery of the liver. Segmental or general lobular or cystic dilatation is reported and may be caused by acquired distal or intrahepatic obstruction or congenital anomalies such as type 4 and 5 choledochal cysts [2].

Malformation of the Biliary System

Biliary Atresia

Biliary atresia is an obstructive condition caused by progressive sclerosis of the extrahepatic bile ducts that, if untreated, leads to cirrhosis, liver failure, and eventually death. It is a relatively rare condition (incidence 1:15,000) with a variable incidence based on ethnicity and a slight female preponderance. The etiology of this entity remains unknown, though some postulate intrauterine viral infection, genetic mutation, vascular or metabolic insult, or dysfunctional immune response. There are three main types of biliary atresia: atresia of the CBD (type I), atresia of the common hepatic duct (type IIa) or atresia of the CBD and the common hepatic duct (type IIb), and atresia of all extrahepatic bile ducts up to the porta hepatis (type III). A great majority of patients have type III. A cystic form of biliary atresia can be confused with a type 1 choledochal cyst .

First described in the literature in 1891, biliary atresia was a universally fatal disease until the development of the Kasai hepatic portoenterostomy procedure in the 1950s, which allowed for drainage of the biliary system. The Kasai procedure continues to be the primary operation with liver transplant being the secondary option if the Kasai is unable to reverse the bile stasis and thereby suspend the cirrhosis progression. Early intervention within the first 2 months of life improves patient outcomes, with overall 5-year patient survival currently approaching 90 % [4].

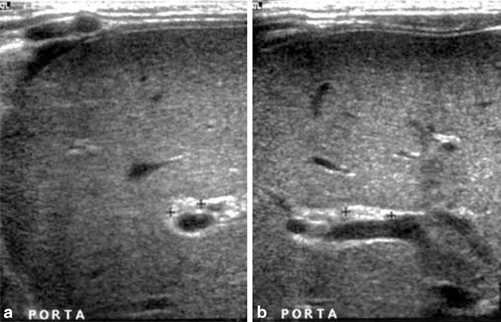

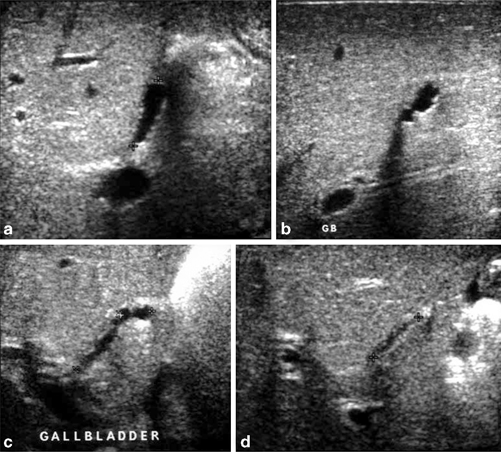

The clinical presentation for biliary atresia is a jaundiced infant with hepatomegaly and pale stools. The diagnosis of biliary atresia is made with a battery of tests that includes liver function tests, hepatitis serologies, tissue biopsy and hepatobiliary ultrasonography, as well as transcystic cholangiogram. Ultrasound demonstrates several characteristic features of biliary atresia. In a study of 30 neonates, absence of the common bile duct had an 83 % sensitivity, 71 % specificity, positive predictive value of 90 %, and negative predictive value of 56 % [5]. However, this criterion should not be used in isolation as a patent distal CBD can be found in up to 20 % of biliary atresia cases [6]. A study of 56 infants evaluated the diagnostic value of the “triangular cord,” a triangular or bandlike periportal echogenicity (3 mm or greater in thickness), which corresponds clinically to a cone-shaped fibrotic mass cranial to the portal vein bifurcation (Fig. 6.3a and b). This finding has a diagnostic accuracy of 94 %, with 84 % sensitivity, and 98 % specificity [7]. In patients with biliary atresia , the gallbladder is absent or shrunken and irregular. Tan and colleagues describe the “gallbladder ghost triad” diagnostic criteria, defined as gallbladder length < 1.9 cm, lack of smooth/complete echogenic mucosal lining with an indistinct wall, and irregular/lobular contour (Fig. 6.4a, b, c and d). Out of 31 patients with biliary atresia, 30 met all three sonographic criteria [8].

Fig. 6.3

(a) and (b) “Triangular cord” sign in an infant with biliary atresia, a triangular or bandlike periportal echogenicity (3 mm or greater in thickness), which represents a cone-shaped fibrotic mass cranial to the portal vein bifurcation. Transverse (a) and longitudinal (b) views (with permission from Poh et al. Biliary atresia: making the diagnosis by the gallbladder ghost triad. Pediatr Radiol 2003; 33:311–315, license number 3637101328502)

Fig. 6.4

(a–d) The “gallbladder ghost triad” in patients with biliary atresia. Longitudinal scans of the gallbladder in a (a) 2-week-old male, (b) 3-week-old female, (c) 5-week-old male, and (d) 6-week-old male, demonstrating a short gallbladder length, an irregular or lobular contour, and a relatively indistinct lining and wall (with permission from Poh et al. Biliary atresia: making the diagnosis by the gallbladder ghost triad. Pediatr Radiol 2003; 33:311–315, license number 3637101328502)

After the Kasai procedure, ultrasound is utilized to monitor the patency of the hepatic vessels and health of the native liver. The sonographic finding of the bile lakes (Fig. 6.5), or clusters of fused damaged bile ducts that form as a result of bile stasis and inflammatory destruction of the bile ducts [9], is thought to be associated with poor prognosis. In one study, the presence of bile lakes predicted a greater number of episodes of cholangitis in the long term [10]. This finding can also be seen in Caroli’s disease, or Type 5 choledochal cyst .

Fig. 6.5

Bile lakes (arrow) in the left lobe of a patient with biliary atresia after Kasai procedure

Ultrasound is a vital component in the workup of patients with biliary atresia yielding valuable information in this challenging patient population, and should not be replaced by liver biopsy or hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid (HIDA) scan only. Ten percent of children with biliary atresia can have associated anomalies, including polysplenia, azygous continuation of the inferior vena cava, preduodenal portal vein, hepatic arterial anomalies, and bilaterally bilobed lungs—these diagnoses would be missed with a more limited imaging modality [11]. Ultrasound also has the benefit of excluding other causes of jaundice such as choledochal cyst or inspissated bile syndrome.

Choledochal Cyst

A choledochal cyst is a congential or acquired dilation of the bile duct. Infants typically present with jaundice or an abdominal mass , while older children can present with abdominal pain and vomiting. The most commonly utilized classification schema by Todani includes five types of choledocal cyst—Type I: dilation of the CBD, Type II: diverticulum of the CBD, Type III: choledochocele (dilatation of the terminal CBD within the duodenal wall), Type IV: multiple cysts of the extrahepatic and intrahepatic ducts, and Type V: single or multiple intrahepatic duct cysts (Caroli disease). Type I is by far the most common, followed by Type IV. Pancreatitis and cholangitis are known complications of choledochal cysts; malignant transformation has been described but is rare and typically limited to adults. Surgical management involves complete cyst excision with a bilio-enteric anastomosis [12].

Ultrasound is the first-line imaging study of choice for diagnosis and description of choledochal cysts (Figs. 6.6 and 6.7). It permits complete assessment of the shape, size, and position of the cyst, as well as an evaluation of the proximal ducts, vascular anatomy, and hepatic parenchyma [12]. Ultrasound can accurately classify the type of choledochal cyst in a cost-effective and reliable manner. Some literature suggests that ultrasound may be the only imaging modality needed in cases where no intrahepatic biliary ductal dilatation is visualized [13]. However, when dilated intrahepatic ducts are encountered on ultrasound, additional imaging by magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) should be performed in order to distinguish between Type I and Type IV choledochal cysts, as this distinction may alter the operative approach. MRCP is accurate and noninvasive [14]; however, it is more costly and requires the patient to be still and cooperative and has to performed under general anesthesia in young children. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) offers complete characterization of the cyst and ductal anatomy, though it is invasive and can be complicated by perforation, pancreatitis, and hemorrhage [15]. Contrast-enhanced CT may be considered in some patients if an associated tumor is suspected [12].

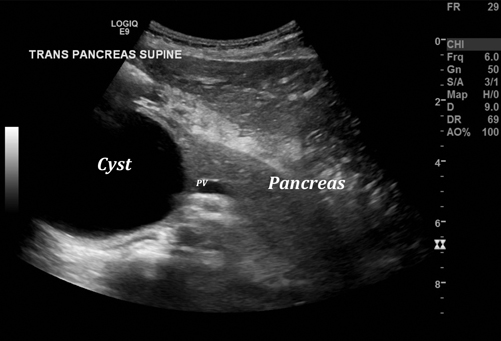

Fig. 6.6

Choledochal cyst, Type 4, adjacent to head of the pancreas (portal vein = PV) (the intrahepatic dilated bile system is not well pictured here)

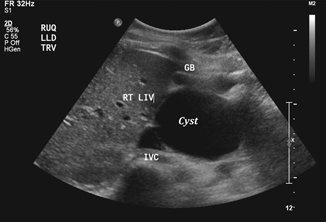

Fig. 6.7

Choledochal cyst, Type 1

Disorders of the Gallbladder

Cholelithiasis

With the wide use of abdominal ultrasound in the workup of pediatric abdominal complaints, symptomatic and asymptomatic cholelithiasis are increasingly common diagnoses in pediatric patients. Older studies report an estimated incidence of cholelithiasis in children between 0.13 and 0.22 % [16, 17]. A more recent study, however, reports an incidence of 1.9 %, with an additional 1.5 % having gallbladder sludge [18

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree