Imaging Presentation

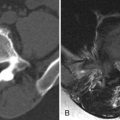

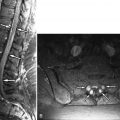

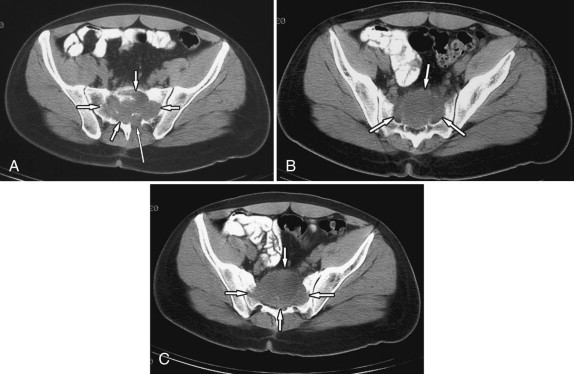

Pelvic radiograph reveals an ill-defined destructive lesion involving the upper half of the sacrum. Computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrates an osteolytic expansile lesion that is destroying the anterior cortex of the sacrum, extending into the presacral soft tissues. A small portion of the tumor extends into the posterior sacral arch on the left ( Figs. 36-1 and 36-2 ) .

Discussion

The entity that has become known as giant cell tumor was first described by Coopers and Travers in 1818. Giant cell tumor of bone was a term introduced by Jaffe and Lichtenstein in 1940. A giant cell tumor (GCT) is an expansile, osteolytic primary bone neoplasm containing giant cells. Giant cell tumors represent approximately 5% to 7% of all bone tumors. The majority of giant cell tumors arise in the ends of the long bones, the knee being the most common site; 3% to 7% of giant cell tumors occur in the spine, and 90% of spinal giant cell tumors arise in the sacrum (see Figs. 36-1 and 36-2 ). Most vertebral giant cell tumors originate in the vertebral body as solitary lesions, but 80% extend into the posterior vertebral arch. Rarely, a GCT may arise in the posterior vertebral arch.

Most patients with spinal or sacral giant cell tumors present between the ages of 20 and 50 with back pain. If the tumor extends into the epidural space or neural foramen, the patient may have myelopathic or radicular symptoms. Patients with cord compression may exhibit hyperreflexia. Sacral or pelvic giant cell tumors often manifest with low back pain and bilateral lower extremity pain. A female preponderance for GCT exists. About one-third of patients have an associated pathologic fracture that can also be the source of back pain and can cause spinal instability.

Histologically, giant cell tumors are comprised of sheets of stromal mononuclear spindle cells containing uniformly distributed multinucleated osteoclastic giant cells. Hemorrhage and necrosis may be present in the tumor. Approximately 15% of giant cell tumors contain areas of aneurysmal bone cyst formation.

The vast majority of giant cell tumors are benign neoplasms, although they are locally aggressive tumors that recur in up to 50% of cases. Approximately 5% to 10% of giant cell tumors are malignant. Some of these tumors have histologic features of the giant cell subtype of osteosarcoma, except that osteoid formation is characteristically absent in malignant giant cell tumors. Malignant giant cell tumor of the tendon sheath (pigmented villonodular synovitis) may also occur. Malignant giant cell tumors have a poor prognosis and may metastasize to the liver, lungs, spine, and other portions of the skeleton; 1% to 5% of giant cell tumors metastasize to the lungs.

Rarely, “benign” giant cell tumors may metastasize to the lungs, the pulmonary lesions being histologically benign. Benign giant cell tumors also rarely manifest as multicentric (multisynchronous) vertebral tumors. Benign or malignant giant cell tumors commonly recur at their initial site of presentation, but rarely also can recur as multicentric benign (metachronous) or malignant (metastatic) tumors. Again rarely, giant cell tumors of the spine or sacrum may have the same histology as appendicular giant cell tumors of the tendon sheath (pigmented villonodular synovitis). Such tumors can be benign or malignant. Sacral giant cell tumors of the tendon sheath may extend into the L5 vertebra to involve the vertebral L5 vertebral body or L5-S1 facet joints. Vertebral giant cell tumors of the tendon sheath are rare but usually involve the facet joints.

Imaging Features

Giant cell tumors in the spine are seen on radiographs or CT images as osteolytic, expansile lesions that have a thin shell of cortical bone at their margins ( Figs. 36-1, 36-2, and 36-3 ). The cortical margin of the tumor is usually not sclerotic. Cortical marginal breakthrough may occur even with benign giant cell tumors ( Figs. 36-2 to 36-5 ) . There is a narrow zone of transition between the expansile mass and the normal adjacent bone. The soft tissue component of the mass within the zone of osteolysis typically does not contain osteoid and therefore clumps of new bone formation are typically absent, although there may be islands of normal trabeculae in this region. On radiographs, sacral giant cell tumors may be difficult to visualize, especially if overlying bowel gas obscures the sacrum, so CT and magnetic resonance (MR) imaging are the imaging modalities of choice for detecting these lesions (see Figs. 36-1 and 36-3 ).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree