Abstract

The primary characteristic of Goldenhar is hemifacial macrosomia/facial asymmetry. The syndrome is likely sporadic, although more recently genetic loci and teratogenic exposures have been reported as likely etiologies. It originates in a defect in the development of the first and second branchial arches. Other common characteristics include microtia, asymmetric mandible hypoplasia, epibulbar dermoids, microophthalmia, periauricular/preauricular tags, and cervical vertebrae anomalies (hemivertebrae). These associated anomalies are most often unilateral but can be bilateral with a more severely affected side. Genetic testing is not currently available for this condition and it remains a clinical diagnosis. Recurrence risk is dependent on etiology. This could range from not increased (general population risk) to up to 50% (autosomal dominant cases).

Keywords

microtia, hemifacial macrosomia, epibulbar dermoids

Introduction

In 1952, Dr. Maurice Goldenhar described a variant of hemifacial microsomia. Although Goldenhar syndrome is frequently listed as synonymous with hemifacial microsomia, it is distinct. Also known as ocular-auriculo-vertebral syndrome, Goldenhar syndrome is a defect in the development of the first and second branchial arches. Characterized by epibulbar dermoids, mandibular asymmetry, and cervical vertebrae anomalies, the syndrome exhibits extreme heterogeneity.

Disorder

Definition

The heterogeneous nature of the syndrome is reflected in the fact that the syndrome has never been precisely defined. The primary feature, definitive of hemifacial microsomia, is asymmetry of the face and ears. Classically, this includes microtia and asymmetric hypoplasia of the mandible. The original report described 30 patients with epibulbar dermoids, lipodermoids, preauricular skin tags, and dysostosis of the mandible and face. In addition, vertebral anomalies such as cervical spine hemivertebrae and scoliosis are reported and, according to some authors, are a requirement. Several cases of radial defects have been noted in association with this syndrome, as well as complex cardiac defects.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

The reported incidence of Goldenhar syndrome ranges from 1 : 3500 to 1 : 26,550, but the most accepted estimation is 1 : 5600. In the largest case series reported (294 patients), the male-to-female ratio was nearly 2 : 1. The majority of cases were Caucasian (78%), although no data regarding the overall makeup of the population were reported, leaving it unclear if this finding was reflective of a variation in incidence of the syndrome by ethnicity, or attributable to the overall population studied.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

The pathologic findings of Goldenhar syndrome appear to originate as a defect in the development of the first and second branchial arches. Animal models have suggested that disruption of the facial circulatory system or interruption of chondrogenesis may be responsible for facial features of the syndrome. In addition, almost half of patients with Goldenhar have an imbalanced fibroblast expression of the protein BAPX1, suggesting that dysregulation of this protein plays a role in the syndrome. Mutations in the coding region of HOXA2, which specifies branchial arch 2 identity, have also been found in patients with microtia phenotypes, further supporting disruption of branchial arch 2 and the association with abnormal craniofacial features.

The majority of reports consider Goldenhar to be a sporadic syndrome. It has been associated with teratogenic exposures such as thalidomide, retinoic acid, and primidone as well as with maternal diabetes. Other associated exposures include tamoxifen and cocaine.

Attempts have been made to identify a genetic locus for Goldenhar. Although traditionally the syndrome is considered sporadic, examination of 97 probands demonstrated that 45% had a family history of relatives, mostly first-degree relatives, affected by ear malformations, mandibular defects, or early-onset hearing loss. This suggests that perhaps this syndrome is characterized by a genetic origin with variable penetrance as opposed to a sporadic occurrence. In addition, at least two families with an apparent autosomal dominant inheritance pattern of the syndrome have been reported. In addition to autosomal dominant inheritance, autosomal recessive and multifactorial inheritance patterns have been observed with Goldenhar. An empiric sibling recurrence risk of 2%–3% is given in the case of a proband with “oculo-auriculo-vertebral spectrum” (OAVS), with normal chromosomes and no family history.

Several cases of 22q11.2 deletions in children with Goldenhar syndrome have been reported. This locus is characterized by low copy repeats and subject to variations in repeat number, suggesting that haploinsufficiency for one or more genes may be responsible for the phenotype. In addition, deletions in this region are associated with DiGeorge syndrome, possibly explaining the frequency of heart defects seen in Goldenhar syndrome.

Others have suggested that Goldenhar syndrome is a 5p15 deletion syndrome. The association of Cri-du-Chat syndrome with deletions on the short arm of chromosome 5 also implicates this region in the development of the branchial arches.

More recently, deletions of the 12p13.33 region involving the WNT5B gene were observed in several patients with OAVS features as well as partially overlapping microduplications on 14q23.1. Other candidate single-gene loci for OAVS have been reported including 14q32 (containing the GSC gene), and potential linkage was suggested at 15q26.2-q26.3.

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation

Findings may be unilateral or bilateral. In patients with bilateral findings, one side is typically more affected than the other ( Table 130.1 ). Some reports state that mental retardation is rare, and others state that it is common. This variation may be resulting from differences in diagnosis. In addition, Goldenhar syndrome may be associated with other nonrandom associations of malformations, such as CHARGE ( c oloboma, h eart defect, a tresia choanae, r etarded growth and development, g enital abnormality and e ar abnormality), and VATER ( v ertebral defects, a nal atresia, t racheo-esophageal fistula, and r enal anomalies).

|

Imaging Technique and Findings

Ultrasound.

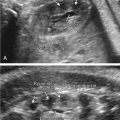

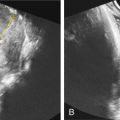

One of the clues to this diagnosis on ultrasound (US) is severe unilateral craniofacial anomalies. Ear abnormalities (microtia, malformed ear, preauricular skin tags) have been diagnosed on US, as well as microophthalmia and anophthalmia ( Figs. 130.1 and 130.2 ). Witters et al. also reported a case of nose hemiatrophy associated with Goldenhar diagnosed on US. Additional findings associated with the syndrome that may be diagnosed on US include cleft lip/palate, vertebral anomalies, skeletal (radial) abnormalities, and cardiac defects.