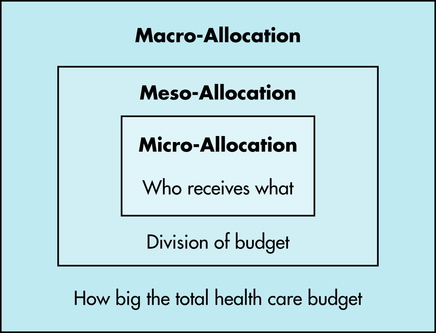

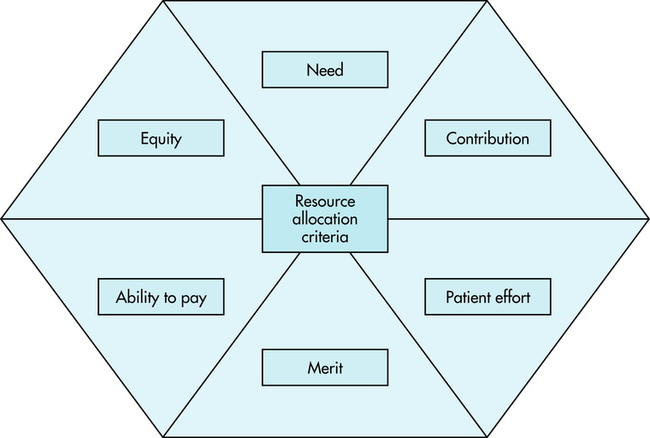

7 After completing this chapter, the reader will be able to perform the following: • Define the right to health care. • List distribution allocation groups. • Identify ethical theories of distribution of health care. • List and use distribution allocation criteria. • Define managed care and its implications for imaging professionals and imaging services. • Define patient-focused care. • Compare concepts of quality care and cost effectiveness. • State the imaging professional’s role in health care distribution. • Define the problems that created the need for managed care. • Identify the history and evolution of managed care. • State the current state of the law with regard to managed care organizations. • Define the concept and origins of modern managed care or risk managed care. • Define the concept of patient-centered or patient-focused care models. • State the legal implications of managed care, risk managed care, and patient-focused care. • Identify legal safeguards provided by proactive approaches to cross-training and streamlining imaging services. • List possible liability issues with regard to denial of authorization of testing and the possible roles of imaging professionals as patient advocates in managed care settings. Society is under many demands to provide health care for all citizens. The increasing costs of health care and the demands of a growing population place other stresses on an increasingly overburdened health care system. Nevertheless, many perceive a need for resources for the distribution of health care services to come from public as well as private sources because “society is under an obligation to the individual to promote the common good.”2 Resources in health care are increasingly expensive and scarce. “A sound theory [of] distribution, then, must provide for priorities and a system of allocating resources that at least regularizes expectations in the light of what is politically and economically possible.”2 Society, patients, and providers must make difficult decisions to aid in this distribution. Questions regarding health care resource allocation can be divided into three groups: macro-allocation, meso-allocation, and micro-allocation.3 Macro-allocation questions ask how big the health care budget will be, who will pay for it, what end it serves, whether there is a right to this care, and what standards will be used to determine these factors. Meso-allocation questions ask how the health care budget will be divided, what health care needs will be addressed, how they will be prioritized, who will deliver these services, and what limits will best serve the efficient meso-allocation of health care. Micro-allocation questions ask who should get what share of the health care budget, whether the present distribution is equitable, how rationing of services is determined, and what factors should be used in the triage of patient needs (Figure 7-1). The prioritization of patient needs influences imaging modalities. For example, breast imaging is often scheduled under pressure by patients and physicians after a lump has been found. Many breast imaging suites examine patients every 15 minutes all day long, and many of these patients have to wait for diagnostic examinations after discovery of an abnormality. Prioritizing these patients according to their needs is difficult. A number of theories have been advanced to aid the triage process (Table 7-1). TABLE 7-1 THEORIES OF DISTRIBUTION: PROS AND CONS IN IMAGING SERVICES The fairness theory tries to tailor health care distribution to balance the dignity and equality of all persons with the inequality of their needs and circumstances. The most important consideration in this theory is the ways in which advantaged and disadvantaged people receive care and who makes these decisions. Inequalities in health care distribution are frowned upon. “Identifying how these differences affect the person can easily lead to subordinating the dignity of the individual to the convenience of the society.”2 According to Armstrong and Whitlock, there are six criteria—need, equality, contribution, ability to pay, effort, and merit—that will aid the health care professional in ethical problem solving when a fair distribution of scarce resources is required.4 These criteria, modified for imaging, are explained as follows: 1. Need. Need seems to be an obvious and useful criterion; however, this is complicated by whose perception of need is used to make the distribution decision. The imaging patient may determine that a much more expensive procedure is needed than the physician has ordered. Thus need is not always the best criterion to use in allocation dilemmas. 2. Equity. The concept of equity rarely serves well as an effective criterion for allocating health care resources. Each imaging patient may require a different type and number of imaging examinations depending on his or her health. It would make no sense to expect each patient to have an equal type and number of examinations. 3. Contribution. The consideration of contribution requires a determination of what an individual might be expected to give to society at a future date. Does the imaging patient have the ability to contribute something useful? Should younger imaging patients be given priority over the elderly? Is there an ethical means of evaluating these future contributions? 4. Ability to pay. Decisions based on ability to pay are of limited benefit in making allocation decisions based on the individual situation. Imaging professionals recognize the values of compassion and giving, and denial of health services based on the imaging patient’s inability to pay is counter to the fundamental belief in generosity and charity. However, the ability to pay may be considered a compelling criterion for consideration when decisions involve elective treatment and the imaging patient was able to choose his or her health plan. At this point the third-party payer may determine the allocation of resources. 5. Patient effort. The imaging patient’s effort may be a useful criterion for patients who fail to heed medical advice or do not make an effort to help themselves. It would be reasonable to consider the value of repeating imaging procedures on a person who continues high-risk behaviors after being warned by a physician to discontinue them. Patient effort may be a controversial criterion because of the complexity of withholding and limiting resources. 6. Merit. The best criterion on which an imaging professional could base an ethical allocation determination might be merit. Merit is the potential to benefit from the additional investment of limited health care resources. The criterion of merit requires that decisions be based on data or evidence. Do the data support the successful outcome of a vascular imaging procedure? Conflicting data and sources may complicate a merit-based decision. The preceding criteria are useful in dealing with ethical dilemmas in allocating imaging resources. They raise important questions when choices are necessary, and they provide the imaging professional with an awareness of what imaging administrators face when solving distribution dilemmas (Figure 7-2). Imaging professionals must understand the health care delivery model of managed care so that they may address the challenges that reforms in health care distribution have presented to imaging services. Managed care is an all-encompassing term that includes any type of system to coordinate the care and treatment of patients. Managed care is designed to provide better access, improved outcomes, more efficient use of resources, and controlled costs for the patient.5 More simply, managed care is any type of delivery and reimbursement system that monitors or controls the type, quality, use, and costs of health care.6 The aim of managed care is to reduce unnecessary or inappropriate care and reduce costs (Box 7-1).7

Health Care Distribution

ETHICAL ISSUES

SCARCITY AND DISTRIBUTION

DISTRIBUTION ALLOCATION GROUPS

DISTRIBUTION THEORIES

Theory

Pros

Cons

Egalitarian

All persons have equal access to all imaging services

Patients’ needs are different; scheduling and reimbursement would be different

Entitlement

All persons have needs

Patients must be involved in a contract to pay for services; theory more concerned with cost value of treatment instead of the intrinsic value of the service to the patient

Fairness

Balances dignity and equality of all persons with the inequality of their needs and circumstances

Identifying the differences (inequality of needs) can lead to subordinating the dignity of the individual to the convenience of the society

Utilitarian

Recommends providing the greatest good for the greatest number of people

Identifies patients as a group rather than as individuals

Fairness Theory

Distribution Decision-Making Criteria

HEALTH CARE DELIVERY MODEL AND MANAGED CARE

Health Care Distribution