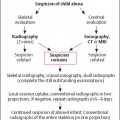

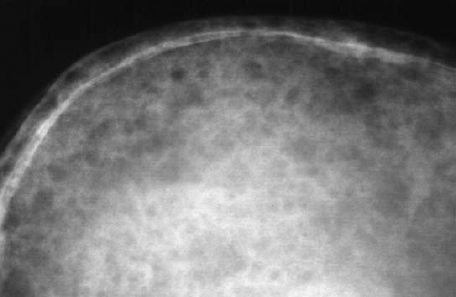

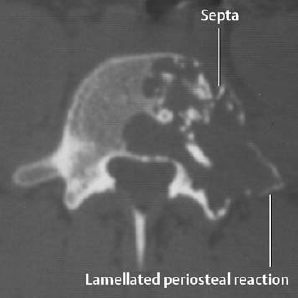

4 Hematologic Disorders Synonyms: multiple myeloma, Kahler disease. Age prevalence: Ages 40 to 80, with men more frequently affected than women. Location: Multiple lesions are frequently found in the skull, spine, ribs, pelvis, and femur. Diffuse lesions of the peripheral skeleton are usually associated with extensive involvement of the axial skeleton. Lesions of the mandible are frequently present. Prognosis: Determined by the type of immunoglobulin. The mean survival time after the first symptoms is 3–4 years. Death is caused by renal insufficiency in 60% of patients. Laboratory values: Detection of paraproteins by means of electrophoresis and of Bence Jones proteins in the urine. Other findings include anemia, elevated sedimentation rate, positive Coombs test, positive rheumatoid factor, hypercalcemia, hyperuricemia, and elevated serum protein from globulin factors. Exception: nonsecretory myeloma (1–3% of myelomas). Some locations show typical features: In general, the bone marrow (especially of the axial skeleton) is homogeneously affected (Fig. 4.7), but multiple round foci can occur (Fig. 4.9). By combining conventional and fat-suppressed sequences, high sensitivity can be achieved (though at the cost of low specificity). The major indications for MRI are assessing the extent of the lesions and their relationship to surrounding anatomic structures. MRI also serves to monitor therapy by following extent, enhancement, and possible fatty conversion during chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Fig. 4.1 Plasmocytoma of the skull with typical osteolytic lesions. Fig. 4.2 Plasmocytoma. Solitary finding in a 25-year-old man. Septated vertebral destruction with lamellated periosteal reaction. Fig. 4.3 Plasmocytoma. Large osteolytic destruction in the proximal femur. This is a nonspecific radiographic finding. Fig. 4.4 Plasmocytoma of the femur. Extensive osteolytic lesions with medullary and subcortical radiolucencies. Note the endosteal scalloping of the cortex, a finding frequently seen in the proximal femur and humerus. Fig. 4.5 Plasmocytoma of the distal radius. There is osteolysis, medullary expansion with cortical thinning and a pathologic fracture. Note the lack of sclerosis which is typical. Osteolysis with expansion (solitary or multiple) also occurs with:

Plasmocytoma

Neoplastic proliferation of the plasma cells primarily affecting the red marrow which can lead to granulocytopenia, thrombopenia, and anemia. Extraosseous manifestations most frequently occur in the spleen, liver, and lymph nodes. Secondary manifestations include renal failure from tubular damage caused by monoclonal immunoglobulins and amyloidosis.

Neoplastic proliferation of the plasma cells primarily affecting the red marrow which can lead to granulocytopenia, thrombopenia, and anemia. Extraosseous manifestations most frequently occur in the spleen, liver, and lymph nodes. Secondary manifestations include renal failure from tubular damage caused by monoclonal immunoglobulins and amyloidosis.

The clinical findings, reflecting the excessive production of abnormal plasma cells, consist of bone pain, weakness, fatigue, fever, weight loss, hemorrhage, and neurologic symptoms. About 6% of the patients develop hepatosplenomegaly in the course of the disease.

The clinical findings, reflecting the excessive production of abnormal plasma cells, consist of bone pain, weakness, fatigue, fever, weight loss, hemorrhage, and neurologic symptoms. About 6% of the patients develop hepatosplenomegaly in the course of the disease.

There are several manifestations, which coexist:

There are several manifestations, which coexist:

Bone scintigraphy does not usually show increased uptake in multiple myeloma. However, the sensitivity of bone scans is not as low as stated in all major textbooks. Bone marrow scintigraphy is considerably more sensitive (detection of ‘cold spots’) but is less specific since benign lesions likewise show decreased uptake in bone marrow. Furthermore, since they no longer contain hematopoietic bone marrow in adults, the extremities are not imaged with confidence. In conclusion, scintigraphy is not recommended for routinely determining the extent of plasmocytoma (see MRI).

Bone scintigraphy does not usually show increased uptake in multiple myeloma. However, the sensitivity of bone scans is not as low as stated in all major textbooks. Bone marrow scintigraphy is considerably more sensitive (detection of ‘cold spots’) but is less specific since benign lesions likewise show decreased uptake in bone marrow. Furthermore, since they no longer contain hematopoietic bone marrow in adults, the extremities are not imaged with confidence. In conclusion, scintigraphy is not recommended for routinely determining the extent of plasmocytoma (see MRI).

MRI has diminished the role of CT, but this modality remains valuable for assessing osseous destruction of the spine and facial bones (Fig. 4.2).

MRI has diminished the role of CT, but this modality remains valuable for assessing osseous destruction of the spine and facial bones (Fig. 4.2).

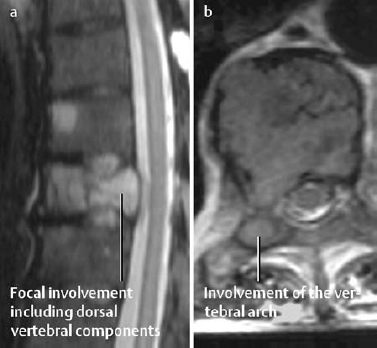

Lesions have low signal intensity on T1-weighted and variable signal intensity on T2-weighted images, ranging from high signal intensity to low signal intensity relative to fat.

Lesions have low signal intensity on T1-weighted and variable signal intensity on T2-weighted images, ranging from high signal intensity to low signal intensity relative to fat.

In 10% of cases plasmocytoma is associated with amyloidoses.

In 10% of cases plasmocytoma is associated with amyloidoses.

The literature is incorrect in stating that plasmacytoma spares the vertebral pedicles in contradistinction to metastases. Both of these processes can involve the pedicles.

The literature is incorrect in stating that plasmacytoma spares the vertebral pedicles in contradistinction to metastases. Both of these processes can involve the pedicles.

| Myeloma | Metastases |

| Relatively well-demarcated, round to ovoid lesion | Indistinct outlines of different sizes |

| Cortical scalloping (cortical destruction less frequent) | Cortical destruction frequent |

| Diffuse involvement of the axial skeleton (see MRI) | Asymmetric involvement of the axial skeleton |

| Diffuse osteosclerosis rare | Diffuse osteosclerosis possible (osteoblastic metastases) |

| Diffuse osteoporosis frequent | Diffuse osteoporosis less frequent |

Glossary

Solitary plasmacytomas are quite rare and can occur in young patients. They often present with neurologic findings. Skeletal manifestations are more frequent in the spine and pelvis, but can be observed in other skeletal regions and even outside the skeletal system. Many patients found to have a solitary lesion at the time of diagnosis develop multiple lesions during the course of the disease.

The lesions can be lobulated, expansile, or purely osteolytic without expansion. Sclerotic lesions are extremely rare.

Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia consists of a neoplastic proliferation of B lymphocytes and is characterized by the pathologic production of monoclonal IgM.

Skeletal manifestations are nonspecific and resemble those of plasmacytoma. These include osteoporosis, bone marrow expansion with endosteal erosions, osteolytic destruction, and secondary vertebral compression. Compared to plasmocytoma, osseous destruction is less frequent, but bone marrow expansion is more pronounced. The disease can also be complicated by avascular necrosis of the femoral head caused by ‘sludging’ from the hyperviscosity of the blood.

POEMS syndrome (polyneuropathy, organomegaly, endocrinopathy, M-protein, skin changes): Osteosclerotic lesions with osseous proliferations at the entheses (tendon and ligament insertions) are generally found. Irregular bone apposition along the dorsal vertebral elements as well as around the SI and costovertebral joints can help to confirm the diagnosis (Fig. 4.10).

Fig. 4.7 Plasmocytoma of the spine. a T1-weighted, b T2-weighted SE sequence. Diffuse low signal intensity involving the vertebral bodies. Collapse of the third thoracic vertebral body with compression of the spinal cord.

Fig. 4.8 Plasmocytoma of the scapula with sclerotic rim following chemotherapy. A rare finding.

Fig. 4.9 Atypical plasmocytoma, MRI. a STIR sequence: high signal focal involvement including dorsal vertebral components. b T2-weighted TSE sequence indicating involvement of the vertebral arch.

Fig. 4.10 POEMS syndrome with osteosclerosis.

Leukemias

The clinical signs of acute leukemia are manifestations of ineffective hematopoiesis: anemia, hemorrhage, infection, fever. The chronic leukemias are clinically dominated by organ infiltration: hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy (with chronic lymphocytic leukemia), and bone marrow infiltration with anemia. The late stages are characterized by increased susceptibility to infections.

The clinical signs of acute leukemia are manifestations of ineffective hematopoiesis: anemia, hemorrhage, infection, fever. The chronic leukemias are clinically dominated by organ infiltration: hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy (with chronic lymphocytic leukemia), and bone marrow infiltration with anemia. The late stages are characterized by increased susceptibility to infections.

Age distribution: The majority of patients are older than 60 years, and chronic leukemias are rare in children. Acute leukemias can occur at any age, but are most prevalent in patients under 20 (acute lymphocytic leukemia) and over 60 (acute myelocytic leukemia) years of age.

Acute Leukemia in Children

Radiologic findings include diffuse osteoporosis, radiolucent metaphyseal bands, osteolytic lesions, periosteal reaction, and osteoporosis (Figs. 4.11, 4.12). Sutural diastasis of the skull is another, though rarely observed, finding.

Radiologic findings include diffuse osteoporosis, radiolucent metaphyseal bands, osteolytic lesions, periosteal reaction, and osteoporosis (Figs. 4.11, 4.12). Sutural diastasis of the skull is another, though rarely observed, finding.

Diffuse osteoporosis: Generalized diffuse osteoporosis is always a suspicious finding in children. This process can lead to vertebral compression fractures (Fig. 4.13).

Radiolucent metaphyseal bands: These are probably caused by an altered circulation that interferes with regular osteogenesis. If seen after the second year of life, radiolucent metaphyseal bands are fairly characteristic of leukemia. In addition, bands of increased density can be observed adjacent to the radiolucent bands (Fig. 4.11).

Osteolytic lesions: These can be observed as permeative or moth-eaten destruction in both tubular and flat bones. Metaphyseal radiolucencies can extend into the diaphysis. Furthermore, osseous destruction can affect the skull, pelvis, ribs, and shoulder girdle (Fig. 4.12).

Periosteal reaction: These can accompany lytic lesions and are induced by subperiosteal infiltration by leukemic cells and hemorrhage. Periosteal reaction appears most frequently along the long tubular bones (Fig. 4.11).

Radiolucent metaphyseal bands can also develop with other pediatric systemic disorders such as toxoplasmosis, rubella, cytomegaly, juvenile chronic polyarthritis, rickets, and neuroblastomas. They can also rarely be seen after methotrexate therapy as a result of arrested osteoblastic activity.

Radiolucent metaphyseal bands can also develop with other pediatric systemic disorders such as toxoplasmosis, rubella, cytomegaly, juvenile chronic polyarthritis, rickets, and neuroblastomas. They can also rarely be seen after methotrexate therapy as a result of arrested osteoblastic activity.

In addition, osteolytic lesions and periosteal reactions can be observed in children with sickle cell anemia, metastases (retinoblastoma, embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma) and infections.

Chronic Leukemia in Adulthood

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Plasmocytoma is a monoclonal B cell lymphocytoma characterized by:

Plasmocytoma is a monoclonal B cell lymphocytoma characterized by:

A solitary lesion or a small number of lytic lesions are indistinguishable from primary osseous lesions, metastases, or infection. Multiple small osteolytic foci (less than 5 mm) can be found with

A solitary lesion or a small number of lytic lesions are indistinguishable from primary osseous lesions, metastases, or infection. Multiple small osteolytic foci (less than 5 mm) can be found with Leukemias consist of autonomous proliferations of hematopoietic cells together with a blocked differentiation caused by neoplastic transformation of the pluripotent hematopoietic stem cells with variable involvement of different cell types. Based on the lineage of the proliferating cell types, lymphatic and myelocytic leukemias are differentiated, each following either an acute or chronic course.

Leukemias consist of autonomous proliferations of hematopoietic cells together with a blocked differentiation caused by neoplastic transformation of the pluripotent hematopoietic stem cells with variable involvement of different cell types. Based on the lineage of the proliferating cell types, lymphatic and myelocytic leukemias are differentiated, each following either an acute or chronic course.