Abstract

Hepatomegaly can occur in maternal diabetes, fetal infection, metabolic/storage disease, and in genetic syndromes. Structural fetal hepatic anomalies include tumors (usually primary, rarely metastatic), calcifications, cysts, and biliary anomalies. Many of these conditions can be diagnosed prenatally by ultrasound.

Keywords

calcifications, hepatic tumor, cysts, hemangioma, hepatoblastoma

Introduction

Structural fetal hepatic anomalies include tumors (usually primary, rarely metastatic), calcifications, cysts, hepatomegaly, and biliary anomalies. Fetal biliary anomalies are discussed in Chapter 25 . Many of these conditions can be diagnosed prenatally by ultrasound (US).

Hepatic Tumors, Calcifications, and Cysts

Solid hepatic tumors are rare, accounting for approximately 5% of perinatal neoplasms. They include benign and malignant primary neoplasms and metastases of nonhepatic cancers. Hepatic tumors appear as intraperitoneal masses, detected prenatally by US and postnatally by palpation. The main tumors are hemangioma, mesenchymal hamartoma, and hepatoblastoma.

Hemangioma

Definition

Hemangioma is a benign tumor characterized by increased angiogenesis. It may occur in various organs.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Hemangioma is the most common primary fetal hepatic tumor and accounts for about 60% of all fetal hepatic tumors.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Hemangioma is a benign vascular tumor characterized by substantial perinatal growth of single or multiple nodules, followed by slow involution during childhood.

Mesenchymal Hamartoma

Definition

Mesenchymal hamartomas are composed of hepatocytes, biliary elements, and connective tissue. This hepatic tumor has traditionally been regarded as a hamartoma. However, cytogenetic studies have suggested that this tumor should be considered a true neoplasm. Biochemical markers such as maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein and beta-human chorionic gonadotropin may be elevated.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Mesenchymal hamartoma is the second most common liver tumor. About one-third of all perinatal hepatic tumors are hamartomas.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Mesenchymal hamartoma is a benign tumor that consists of hepatocytes, biliary components, and fibrous tissue and may form a solid or multicystic mass.

Hepatoblastoma

Definition

Fetal hepatoblastoma arises from undifferentiated embryonal tissue and occurs as epithelial or epithelial/mesenchymal.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Hepatoblastoma is the most common malignant fetal tumor. About 16% of perinatal hepatic tumors are hepatoblastoma. The female-to-male ratio is 1.6 : 6.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Most hepatoblastomas are found in the right lobe; a few arise from both lobes with a multiple nodule aspect. This preference for the right lobe might be explained by the different blood oxygen tensions of the vessels supplying the two lobes. The hepatic vein delivers oxygen-saturated blood to the left lobe, whereas the portal vein supplies less saturated blood to the right lobe, which facilitates the development of hepatoblastoma.

Hepatic Calcifications

Definition

Calcifications represent local accumulations of calcium, usually caused by infection or inflammation, hypoxia, or necrosis.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

The incidence of fetal hepatic calcifications has been reported to be 1 : 1750 at 15 to 26 gestational weeks.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Hepatic calcifications usually have a peritoneal (infection, meconium peritonitis), parenchymal (infection, tumor), or vascular origin or cause. Other malformations are present in 21% of fetuses with hepatic calcifications.

Hepatic Cysts

Hepatic cysts occur in isolation, as part of genetic syndromes such as autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease, or as manifestations of biliary anomalies (see Chapter 25 ).

Definition

A cyst is a structure composed of a distinct wall with a liquid or solid content. In adults, hepatic cysts include parasitic and nonparasitic cysts, but fetal parasitic cysts have not yet been reported. Hepatic cysts may be solitary or multiple, such as in congenital polycystic disease of the kidney and liver, congenital dilatation of intrahepatic bile ducts (Caroli disease), and congenital hepatic fibrosis.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

The incidence of hepatic cysts is low in neonates and increases with age. Approximately 2.5% of the general population is affected. The female-to-male ratio is 4 : 1. The incidence of fetal hepatic cysts has been reported as 1 : 7786 fetuses at 13 to 17 weeks’ gestation.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

The etiology of isolated solitary hepatic cysts is unknown. Aberrant bile ducts may cause accumulations of bile, leading to hepatic cysts (see also Chapter 25 ).

Congenital Intrahepatic Shunts

Definition

Congenital intrahepatic shunts are characterized by anomalous communications among hepatic vessels.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Intrahepatic arteriovenous shunts are exceedingly rare, and their prevalence is unknown.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Anomalous communications among hepatic artery, vein, and portal vein account for arteriovenous, arterioportal, and portosystemic shunts.

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT), an autosomal dominant condition, leads to mucocutaneous telangiectasias and visceral arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) commonly detected in the cerebral, pulmonary, and hepatic circulation, which might be revealed antenatally. When fetal hepatic AVMs are suspected in HHT patients, genetic testing should be offered.

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation

Hemangioma.

The growth of nodules may cause hepatic (subcapsular) hematoma due to spontaneous bleeding during involution, anemia, hydrops, hydramnios, thrombocytopenia, disseminated intravascular coagulation and localized consumption coagulopathy (Kasabach-Merritt syndrome), and neonatal cardiac failure secondary to massive arteriovenous shunting inside the tumor.

Fetal blood sampling may be useful to test for thrombocytopenia, allowing optimal perinatal management such as intrauterine platelet transfusion before delivery. Postnatal treatment strategies consist of medical management (steroids and interferon alfa) and interventional modalities (hepatic artery ligation or embolization, surgical resection, or liver transplantation). In prenatally diagnosed liver hemangiomas, treatment with corticosteroids has been attempted. However, spontaneous remission of a hemangioma after birth is common. Half of the affected cases also had hemangiomas of the skin and other organs. Hemangiomas and concomitant chorioangioma or other impairment of the placental architecture have also been reported.

Mesenchymal Hamartoma.

Mesenchymal hamartomas usually increase in size, which necessitates surgery. A few cases show incomplete spontaneous regression, whereas some undergo malignant transformation to undifferentiated (embryonal) sarcoma, although this occurs very rarely. Large tumors may compress the inferior vena cava and the umbilical vein, leading to polyhydramnios and fetal hydrops. Associations with placental pathology and Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome (BWS) have been reported (see also Chapter 109 ).

Hepatoblastoma.

During labor, the fetus is at risk for intraabdominal hemorrhage owing to rupture of hepatoblastoma. Hepatoblastomas can be associated with genetic anomalies and malformation syndromes such as BWS, familial adenomatous polyposis coli, fetal alcohol syndrome, and trisomy 18.

Hepatic Calcifications.

In the presence of hepatic calcifications, a detailed US examination should seek additional structural anomalies, and serologic testing for infections including TORCH ( t oxoplasmosis, o ther [congenital syphilis and viruses], r ubella, c ytomegalovirus, and h erpes simplex virus) and amniocentesis for karyotyping and viral polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing should be discussed. Isolated hepatic calcifications have a good prognosis. The combination of hepatic calcifications with other sonographic abnormalities are associated with increased risk for chromosomal abnormalities, mainly trisomy 13.

Hepatic Cysts.

Most hepatic cysts detected during the early second trimester disappear spontaneously, particularly when the cysts are initially small and peripheral. Most persistent hepatic cysts are asymptomatic and do not need a neonatal surgical intervention. Complications may arise from pressure effects. US-guided in utero needle drainage of hepatic cysts has been reported, but postnatal procedures may still be necessary in symptomatic cysts. Postnatal surgical interventions include total excision, partial excision with marsupialization of the cyst wall, and Roux-en-Y hepatojejunostomy.

Intrahepatic Arteriovenous Shunts.

Arteriovenous shunts in the liver are associated with a high mortality rate. Clinical symptoms depend on the size, type and site of the shunts. Clinically significant arteriovenous shunts result in high-output heart failure. Congenital intrahepatic arterioportal shunts lead to portal hypertension and subsequently to gastrointestinal bleeding, anemia, ascites, diarrhea, and malabsorption. Portosystemic shunts lead to hypergalactosemia, increased bile acid, hepatopulmonary shunt, portopulmonary hypertension, and focal hepatic nodular hyperplasia.

In complex intrahepatic shunts, hepatic resection is the treatment of choice since embolization is associated with increased risk of adverse outcome and might not provide an efficient therapy.

Imaging Technique and Findings

Ultrasound

Hemangioma.

On prenatal US, fetal hepatic hemangiomas may be heterogeneous, but they are usually mixed solid/cystic and hypoechoic compared with normal liver tissue ( Fig. 28.1A ). They typically show increased vascularity on color Doppler examination (see Fig. 28.1B ).

and

and  ).

). Mesenchymal Hamartoma.

Mesenchymal hamartoma appears as a multiloculated cystic mass with different-sized, thin-walled cysts and an anechoic and hypovascular aspect. Color Doppler usually shows no increased vascularity. Hamartomas have been detected by prenatal US, typically in the third trimester of pregnancy. Some fetuses also have polyhydramnios.

Hepatoblastoma.

The US appearance of fetal hepatoblastoma is more irregular and mostly solid, and these lesions show calcifications. On prenatal US, hepatoblastoma appears as a usually single, heterogeneous, circumscribed, echogenic solid mass within the liver with a spoke-wheel appearance ( Fig. 28.2 ). Possible associated US findings are hydramnios and fetal hydrops, which may lead to prenatal or postnatal death.

Hepatic Calcifications.

Hepatic calcifications appear as isolated or sporadic bright echogenic foci ( Fig. 28.3 ).

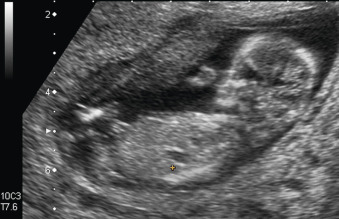

Hepatic Cysts.

Most fetal hepatic cysts are detected in the third trimester, but they also may be identified in the first trimester ( Figs. 28.4 and 28.5 ). Hepatic cysts are usually anechoic spaces surrounded by liver parenchyma. Color Doppler may show vessels in the vicinity of the cyst and the hepatic artery or the portal vein, indicating a biliary origin (see Chapter 25 ).

If multiple hepatic cysts are detected by US, the differential diagnosis includes congenital polycystic disease of the liver and kidney, congenital dilatation of intrahepatic bile ducts (Caroli disease), and congenital hepatic fibrosis. Cystic kidney diseases are discussed in Chapters 15 and 16 .

Intrahepatic Shunts.

In large congenital intrahepatic shunts, considerable dilatation of the suprarenal aorta and hepatic vessels, along with mild cardiomegaly, may be observed at prenatal ultrasound. Doppler spectral analysis of intrahepatic vessels may show arterial traces with little systolic-diastolic flow variation and high-velocity venous signals.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in addition to fetal echocardiography in late gestation may help assess the functional relevance of large hemangiomas. For the diagnosis of mesenchymal hamartoma, fetal MRI may be of additional value.

Hepatomegaly and Fetal Infections

Human cytomegalovirus (CMV) is the most common congenital viral infection and, in the acute phase, manifests with hepatomegaly. Toxoplasmosis, syphilis, and rubella also can cause hepatomegaly. Parvovirus infection is another possible cause of hepatomegaly; it is generally accompanied by splenomegaly and accelerated cerebral peak systolic velocities owing to hyperdynamic fetal circulation caused by fetal anemia and hydrops. Fetal infections are described in detail in Chapter 165 , Chapter 166 , Chapter 167 , Chapter 168 .

Definition

Hepatomegaly means enlargement of the fetal liver. Enlargement can be judged subjectively (e.g., when the liver reaches into the fetal pelvis adjacent to the fetal bladder) ( Fig. 28.6 ). For a more objective and quantifiable assessment, the length of the right lobe of the liver can be measured from the dome of the diaphragm to the tip of the right lobe parallel to the long axis of the fetal trunk ( Fig. 28.7 ). Normal ranges have been reported for fetal liver length ( Fig. 28.8 ).