Abstract

It is important to understand the differential diagnosis for solid and cystic liver lesions. Malignant solid liver lesions include metastases, lymphoma, and primary malignancies such as hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and cholangiocarcinoma (CC). Benign solid liver lesions are most commonly hemangiomas, focal nodular hyperplasia, or adenomas. Malignant cystic liver lesions include metastases, HCC, CC, and biliary cystadenocarcinomas. For benign cystic liver lesions, consider cysts, infections (pyogenic, amoebic, echinococcal), biliary hamartomas (von Myenberg complexes), and biliary cystadenomas. An FDG-avid liver lesion is suspicious for malignancy unless proven otherwise by anatomic imaging or pathology.

Keywords

FDG, PET/CT, liver, gallbladder, biliary, metastases, hepatocellular carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma, hemangioma, focal nodular hyperplasia, adenoma

Liver

The segmental anatomy of the liver is based on the hepatic veins, thus the segmental anatomy of the liver is more difficult to appreciate on contrast computed tomography (CT). The liver is divided into right and left lobes by the middle hepatic vein. The right lobe is divided into anterior and posterior segments by the right hepatic vein, and the left lobe is divided into medial and lateral segments by the left hepatic vein ( Fig. 12.1 ). On a noncontrast CT, this may lead to confusion with defining the left and right hepatic lobes ( Fig. 12.2 ). The falciform ligament may be confused as the structure that separates the left and right hepatic lobes, but this is actually the plane of the left hepatic vein, separating the medial and lateral segments of the left lobe. On a noncontrast CT scan, the intralobar fissure, separating the left and right hepatic lobes, is better approximated by the location of the gallbladder fossa.

When confronted with a focal liver lesion, knowledge of the differential diagnosis for solid and cystic liver masses is valuable. In the differential diagnosis, consider malignancies, including primary malignancies, metastases, and lymphoma, as well as benign etiologies including benign neoplasms and infections.

Let’s start with solid liver lesions ( Fig. 12.3 ). Solid liver lesions may be malignant or benign. Malignant solid liver lesions include metastases, lymphoma, and primary malignancies such as hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and cholangiocarcinoma (CC). Benign solid liver lesions are most commonly hemangiomas, focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH), or adenomas. With this differential diagnosis for solid liver lesions, clinical history and imaging characteristics can then be used to narrow the differential or determine diagnosis. Of course, biopsy may sometimes be required for the definitive diagnosis.

Now let’s consider cystic liver lesions ( Fig. 12.4 ). Cystic lesions may also be malignant or benign. For malignancies, metastases may be cystic, HCC and CC may be cystic, and we would add biliary cystadenocarcinomas. Lymphoma is less likely to be cystic. For benign cystic liver lesions, we would consider cysts, infections (pyogenic, amoebic, echinococcal), biliary hamartomas (von Meyenburg complexes), and biliary cystadenomas. This produces a differential diagnosis that is different from that of solid liver lesions.

With the knowledge of common differentials for solid and cystic liver lesions, we can now address specific scenarios of liver lesions on fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG PET)/CT.

Hepatic Metastases

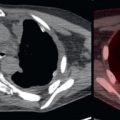

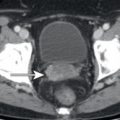

The liver is one of the most common organs for metastatic involvement. In a patient with a known malignancy with a propensity to metastasize to the liver, FDG-avid liver lesions are highly suspicious for liver metastases ( Fig. 12.5 ). FDG-avid liver metastases may be visualized with corresponding low-attenuation lesions on CT; however, the lack of low-attenuation lesions on the corresponding CT does not prevent the diagnosis of metastasis. Several possible reasons may contribute to the lack of an apparent lesion on CT. First and foremost, most FDG PET/CT scans are performed without intravenous contrast, and scans without intravenous contrast will greatly limit the visualization of liver lesions on CT, particularly on soft tissue CT windows. Adjusting the CT window to that of the liver window may help to visualize a corresponding low-attenuation lesion on CT. Second, even with intravenous contrast, FDG PET may demonstrate FDG-avid liver metastases without a corresponding lesion on CT ( Fig. 12.6 ). This is particularly apparent when the patient has hepatic steatosis. In the setting of hepatic steatosis, the low-attenuation liver parenchyma may mask low-attenuation liver lesions which are more apparent on FDG PET.

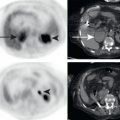

Although much less common, it is also possible to visualize the development of liver metastases on the CT component of the PET/CT before the lesion becomes appreciably FDG avid ( Fig. 12.7 ). The background FDG avidity of the liver may mask small or only mildly FDG-avid liver metastases. To optimize the detection of liver metastases on FDG PET/CT, view the CT images on a liver window, even if the CT was performed without intravenous contrast. A narrow liver window will help to visualize low-attenuation liver metastases from non- or mildly FDG-avid malignancy.

Following therapy, decreases in liver metastases may be apparent by either decreasing size on CT or FDG avidity on FDG PET ( Fig. 12.8 ). In some scenarios, decreases in FDG avidity will better represent treatment response and decreases in size on following treatment of initially FDG-avid pancreatic lymphoma, on CT. This is particularly apparent in the setting of hepatic pseudocirrhosis ( Fig. 12.9 ). Pseudocirrhosis is a result of successful treatment of hepatic metastases, with retraction of the liver capsule in regions of decreasing metastases. This produces a liver contour and appearance similar to that of a patient with cirrhosis but without secondary signs of cirrhosis such as splenomegaly or varices. Pseudocirrhosis is most commonly seen after treatment of patients with breast cancer. The altered morphology of a pseudocirrhotic liver may make it very difficult to determine the extent of residual malignancy on CT.