Diagnosis

Cases

Primary malignant tumors

Chordoma

172

Undifferentiated high-grade pleomorphic sarcoma

27

Chondrosarcoma

18

Ewing Sarcoma

12

Small blue round cell tumor

9

Osteosarcoma

11

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor

3

Fibrosarcoma of bone

2

Malignancy in giant cell tumor of bone

2

Angiosarcoma

1

Subtotal

257

Benign lesions

Giant cell tumor of bone

124

Schwannoma/neurofibroma

75

Aneurysmal bone cyst

8

Bone cyst

9

Osteoblastoma

5

Paraganglioma

5

Hemangioma

4

Desmoplastic fibroma of bone

2

Fibrous dysplasia

2

Angiomatosis, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, Lipoma, Myopericytoma, Osteochondroma, Osteoid osteoma

6

Subtotal

240

Systemic diseases

Metastatic disease

84

Plasma cell myeloma

13

Primary non-Hodgkin lymphoma of bone

8

Subtotal

105

Total

602

7.1 Malignant Tumors

Malignant tumors include primary sarcoma, primary hematopoietic malignancy, and metastatic diseases. Primary sarcoma may derive from bone or soft tissue. The histological type of a primary bone sarcoma is often indicative of the tumor grade. The most common bone sarcomas are of high-grade malignancy. Soft tissue sarcoma occurring in sacrum is rare. Histological type and grade predict tumor behavior. The Federation Nationale des Cenres de Lutte Contre Le (FNCLCC) grading system is well accepted.

7.1.1 Chordoma

Chordoma is the most common primary malignancy occurring in sacrum arising from notochordal rests [2]. Although it is mainly located in the base of the skull, 29.2–60% of chordomas occur in the sacrococcygeal region [3, 4]. It is usually a slow-growing and low-grade tumor, but metastatic disease is seen more frequently in sacral chordomas than in skull base chordomas [5].

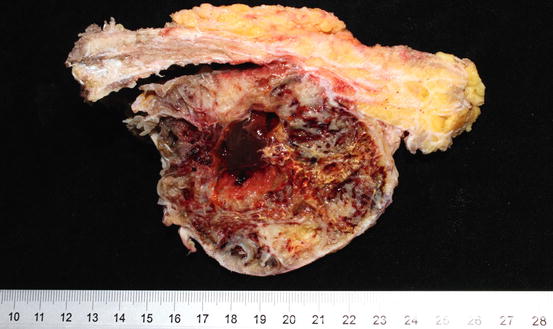

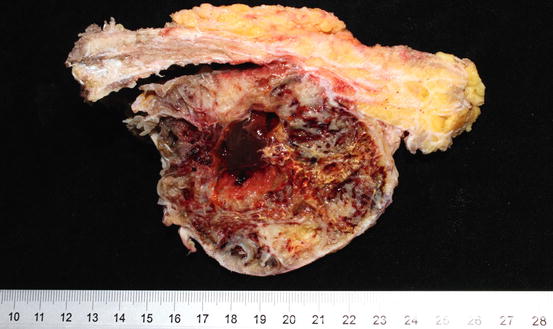

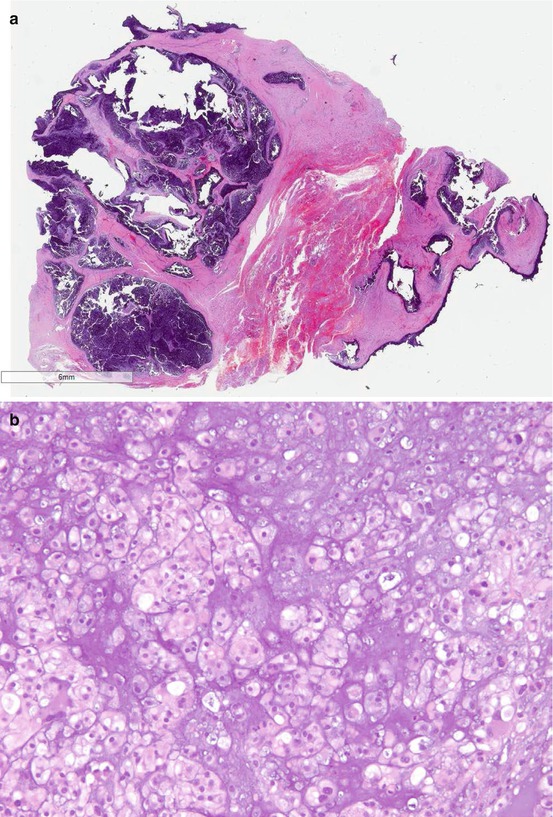

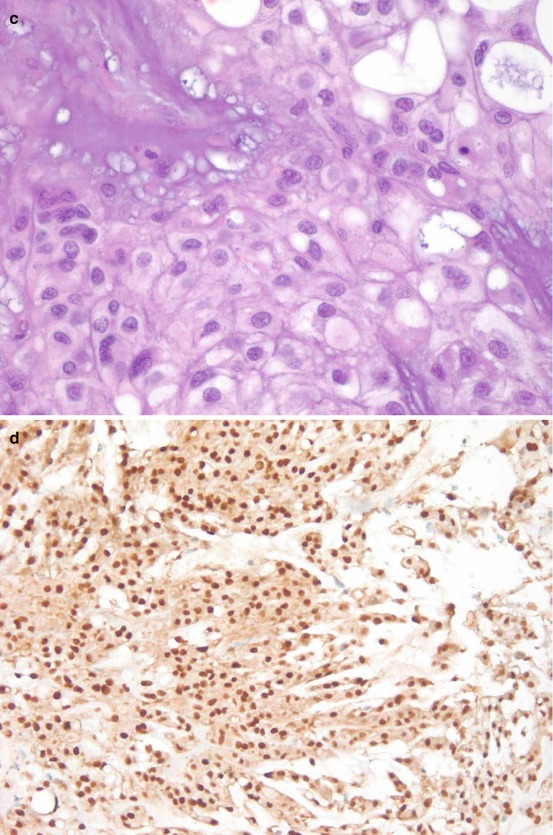

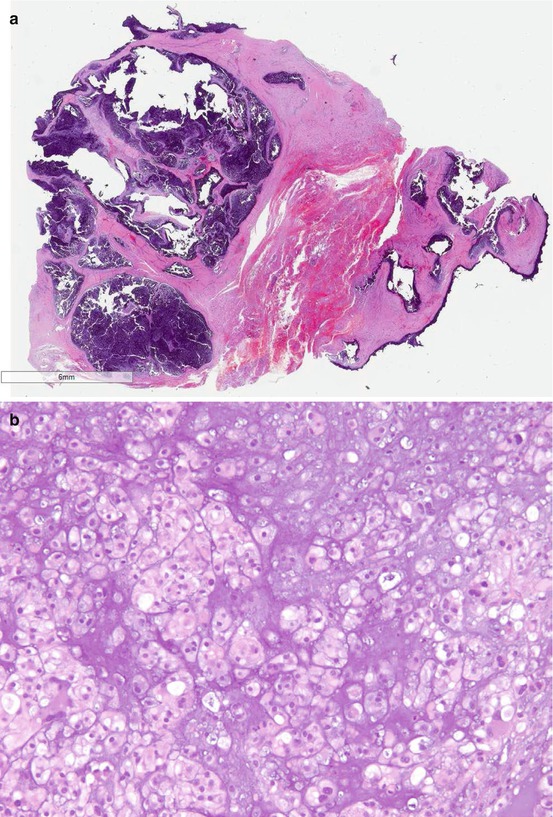

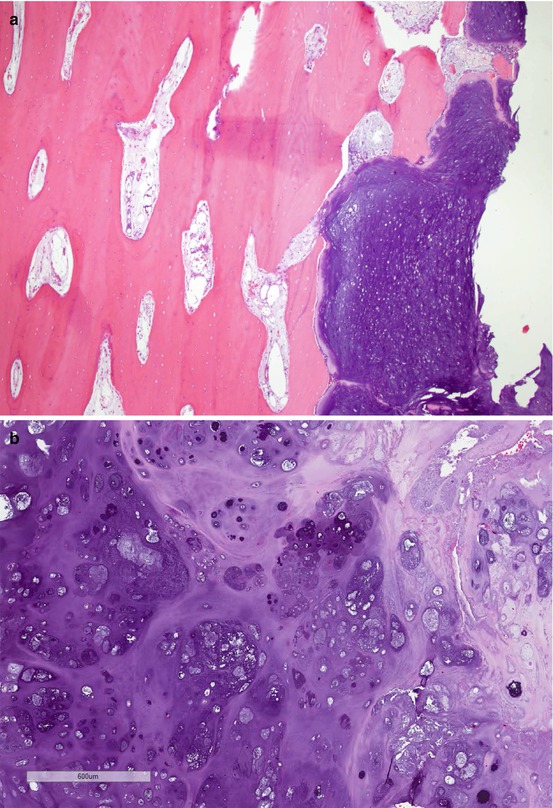

Grossly, the tumor has an expansile, lobulated structure with cortical invasion. The cut surface is gelatinous with chondroid texture (Fig. 7.1). By definition, chordoma is a malignant tumor showing notochordal differentiation [3]. Notochordal differentiation is exhibited by epithelioid cells arranged in nests or cords with clear or eosinophilic cytoplasm; some have vacuolated “bubbly” cytoplasm, so called “physaliphorous cells.” The tumor cells are separated by fibrous septa, which give rise to the lobulated appearance and are embedded in abundant extracellular myxoid matrix. In a low-grade tumor, the nuclei are small with coarse chromatin. In a high-grade tumor, the nuclei may become larger, pleomorphic and with greater mitotic activity.

Fig. 7.1

Gross image of a sacral chordoma

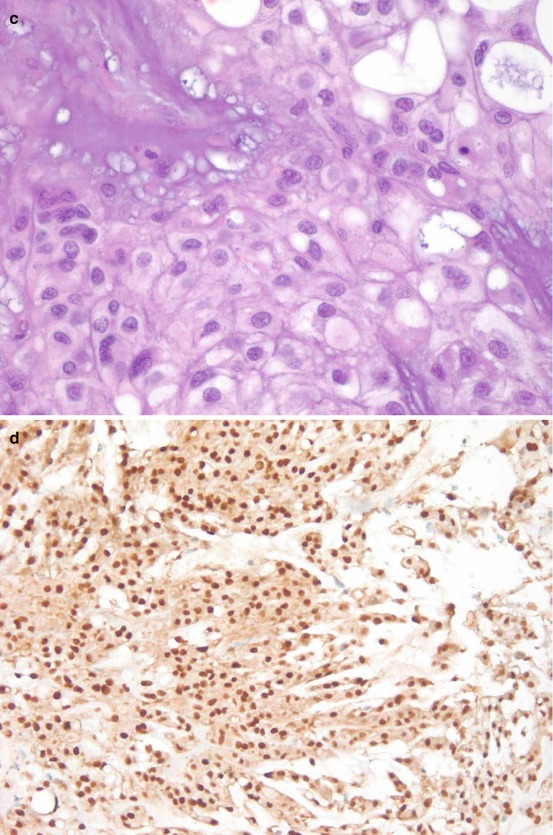

Most of the chordomas are designated as chordomas, not otherwise specified (NOS) [3]. Chondroid chordoma is a rare variant which contains hyaline cartilage component. Its behavior is similar to chordoma, NOS, but it may be confused as chondrosarcoma morphologically. Brachyury is a specific immunohistochemical diagnostic marker for chordoma [6]. Nuclear immunoreactivity to Brachyury is seen in chordoma but not in chondrosarcoma, and is therefore extremely helpful in the differential diagnosis. Figure 7.2 shows the histological and immunohistochemical features of a chordoma. In practice, we prefer to use the more specific monoclonal antibody of brachyury than the polyclonal to prevent false positivity; we also prefer to use non-decalcified specimen for brachyury testing to prevent false negativity. Other traditional helpful positive diagnostic immunohistochemical markers for chordoma include keratin, epithelial membrane antigen, and S-100 protein. New markers such as loss of PTEN and loss of INI-1 expression have recently been found in chordoma [7, 8]. Dedifferentiated chordoma is a high-grade and biphasic tumor which consists of a high-grade undifferentiated spindle cell sarcoma or osteosarcoma in association to chordoma, NOS [3]. Recognizing the conventional chordoma component is the key to this diagnosis because the dedifferentiated component does not express the diagnostic markers described here.

Fig. 7.2

Microscopic images of a chordoma. (a) HE digitalized whole slide image. (b) HE ×200. (c) HE ×600. (d) Brachyury stain ×200

7.1.2 Chondrosarcoma

Chondrosarcoma is a locally aggressive malignant tumor that produces cartilaginous matrix [3]. There are four histological variants of chondrosarcoma: conventional, dedifferentiated, mesenchymal, and clear cell (Table 7.2). The histological grade is the single most important prognostic factor of conventional chondrosarcoma. Chondrosarcoma can be classified on the basis of its location in the bone. Central chondrosarcomas are located in the medullary cavity, peripheral chondrosarcomas arise from the surface of the bone, and periosteal (juxtacortical) chondrosarcomas arise from the surface of the bone and the periosteum [3]. According to its origin, a primary chondrosarcoma arises de novo, and secondary chondrosarcoma is a result of malignant transformation of an enchondroma (central) or osteochondroma (peripheral). All types can affect the pelvic bones, including the sacrum; however, peripheral secondary chondrosarcoma is seen more commonly in younger patients than in central primary chondrosarcoma, which predominantly affects patients more than 50 years of age [9]. The majority of the conventional and dedifferentiated chondrosarcomas exhibits somatic mutations of the isocitrate dehydrogenase genes 1 and 2 (IDH1 and IDH2) [10]. However, this finding is absent in mesenchymal and clear cell chondrosarcoma indicating their different pathogenesis. The presence of (IDH1 and IDH2) mutation can be used to differentiate a chondroblastic osteosarcoma when it is deemed necessary. These molecular findings also warrant further investigation for their role as potential therapeutic targets [11].

Table 7.2

Characteristics of histological variants of chondrosarcoma

Tumor type | Component | Prognosis |

|---|---|---|

Conventional | Chondrosarcoma | Depends on grade |

Grade I | ||

Grade II | ||

Grade III | ||

Dedifferentiated | Low-grade conventional chondrosarcoma plus high-grade dedifferentiated sarcoma or osteosarcoma | Poor |

Mesenchymal | Low-grade conventional chondrosarcoma plus poorly differentiated malignant small round cells | Poor |

Clear cell | Clear cells or chondroblastoma-like cells | Depends on grade |

Note: Usually occurs in the ends of long bones; patients younger than conventional |

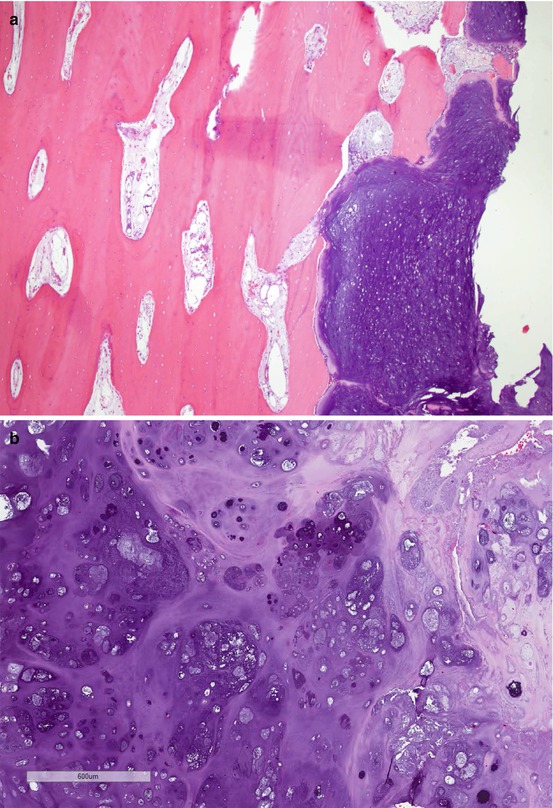

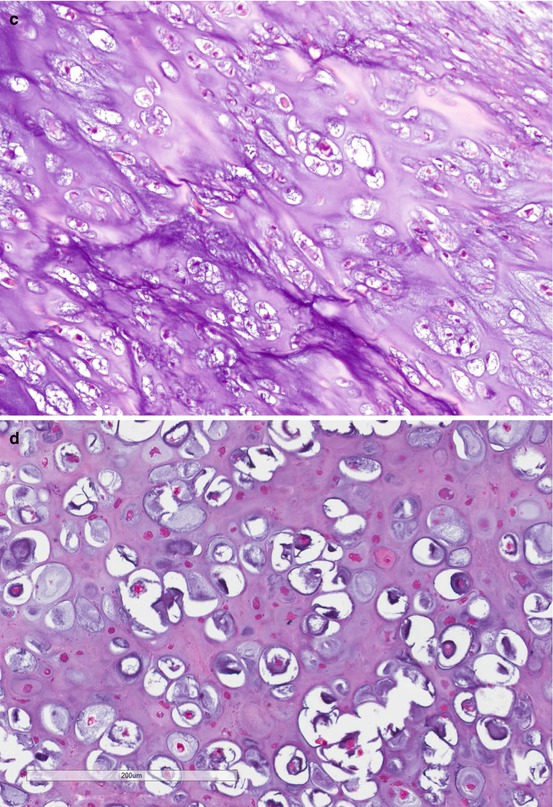

As shown in Fig. 7.3, conventional chondrosarcomas grossly have the cut surface of hyaline cartilage with irregularly lobular appearance. Myxoid, cystic, and calcification changes can be seen. Microscopically, the distinction between enchondroma and grade I chondrosarcoma can be challenging due to overlapping morphological features. A generally accepted minimum diagnostic criteria for chondrosarcoma include hypercellularity, permeation of the host bone, absence of host bone encasement, open chromatin, mucoid matrix, and older patient (age >45 years) [3]. After establishing a diagnosis of chondrosarcoma, the next step is to grade the tumor using the following histological features: cellularity, nuclear size, degree of hyperchromasia, and mitoses. The grade I chondrosarcoma has similar nuclear features of enchondroma, except the architectural changes as described above. Grade III chondrosarcoma exhibits high cellularity, markedly enlarged nuclei, pleomorphic nuclei with nucleoli, and frequent mitoses compared to grade II chondrosarcoma. Tumor grade is the single most important prognostic factor of chondrosarcoma [9, 12]. When a chondrosarcoma has a spectrum of histology from grade I to grade III, it is a good practice to report the percentage of the high-grade component which predicts a worse prognosis. Figure 7.4 is the histological illustration of chondrosarcoma of various grades and dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma.

Fig. 7.3

Gross image of a sacral chondrosarcoma

Fig. 7.4

Microscopic images of chondrosarcoma. (a) Chondrosarcoma invasion of bone. HE ×40. (b) Grade I chondrosarcoma. (c) Grade II. HE ×200. (d) Grade III. (e) Dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma. HE ×400

7.1.3 Ewing Sarcoma

Ewing sarcoma is a high-grade malignancy with small, round tumor cells harboring pathognomonic molecular signatures [3]. Approximately 85% of the Ewing sarcoma harbors a somatic chromosomal translocation t(11;22)(q24;q12) which rearrange EWSR1 gene to fuse with FLI1 gene [13]. The fusion protein EWSR1-FLI1 is an oncoprotein and is responsible for the pathogenesis of Ewing sarcoma [14, 15]. The EWSR1 gene also has many other fusion partners such as the ERG gene [13]. Molecular testing for the signature gene and products are useful in confirming the diagnosis [16, 17]. While reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) may confirm the presence of EWSR1-FLI1 or EWSR1-ERG fusion products, specific for Ewing sarcoma, the detection of rearrangement of EWSR1 gene by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) is not specific, because other sarcomas may harbor EWSR1 gene rearrangements [3].

Primary Ewing sarcoma of the spine including sacrum is uncommon (only 3–10%); while metastatic disease from extraspinal Ewing sarcoma is more frequent. The sacral ala is the most common site for primary Ewing sarcoma of the spine [18, 19]. The prognosis is worse for sacrococcygeal Ewing sarcoma than for extraspinal Ewing sarcoma, usually due to larger tumor size at presentation because of delayed clinical presentation [20].

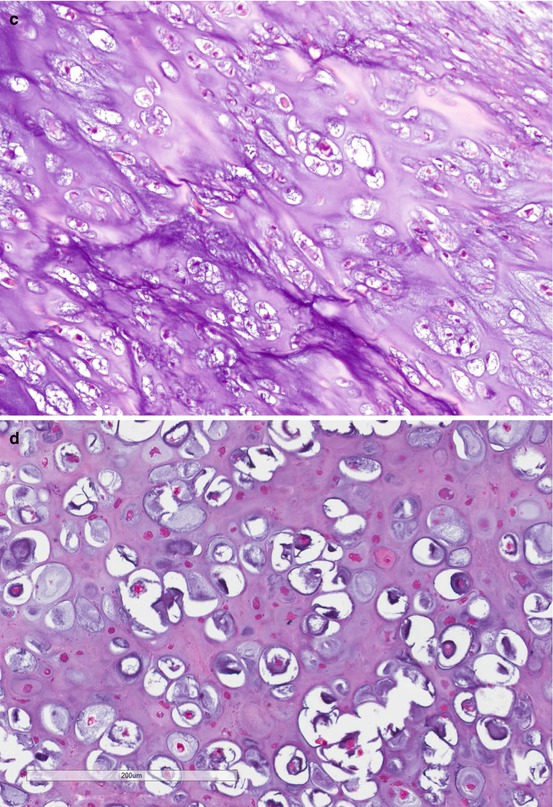

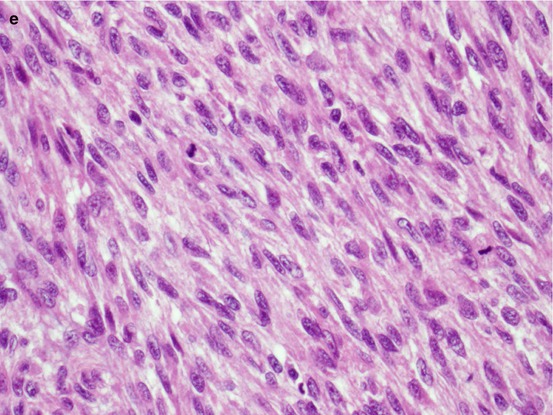

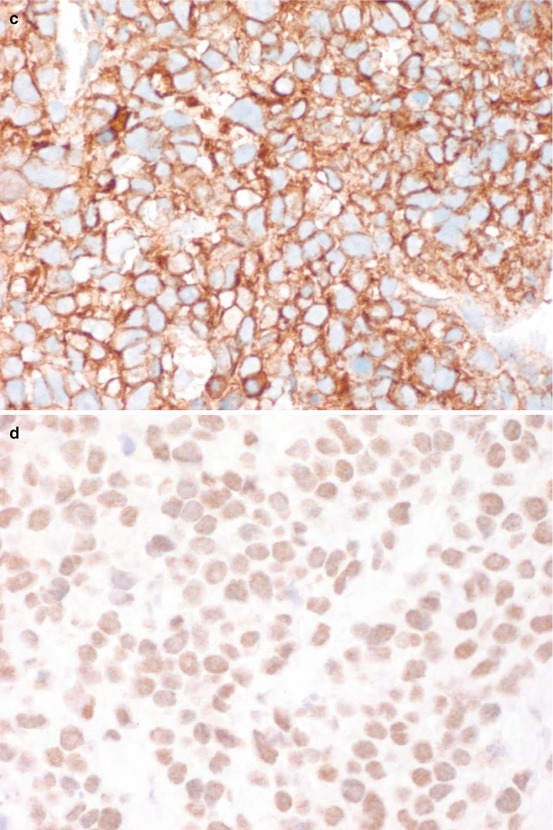

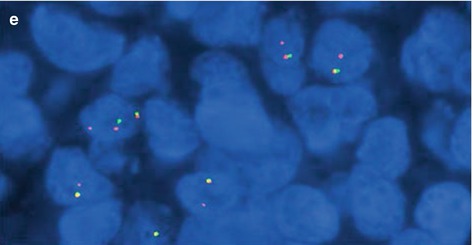

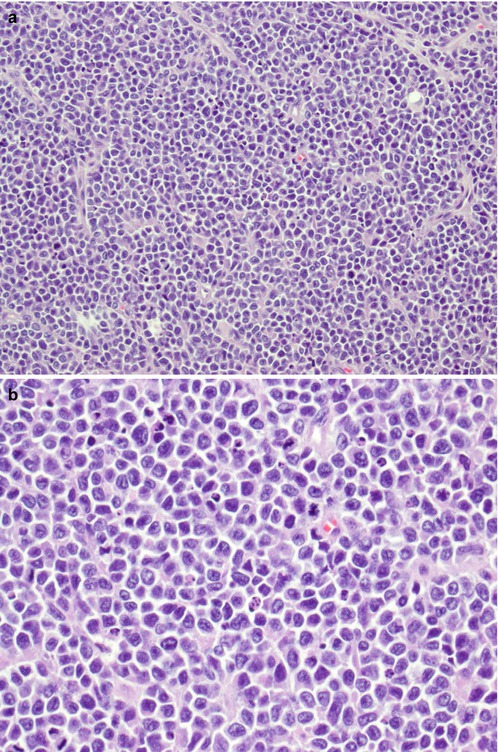

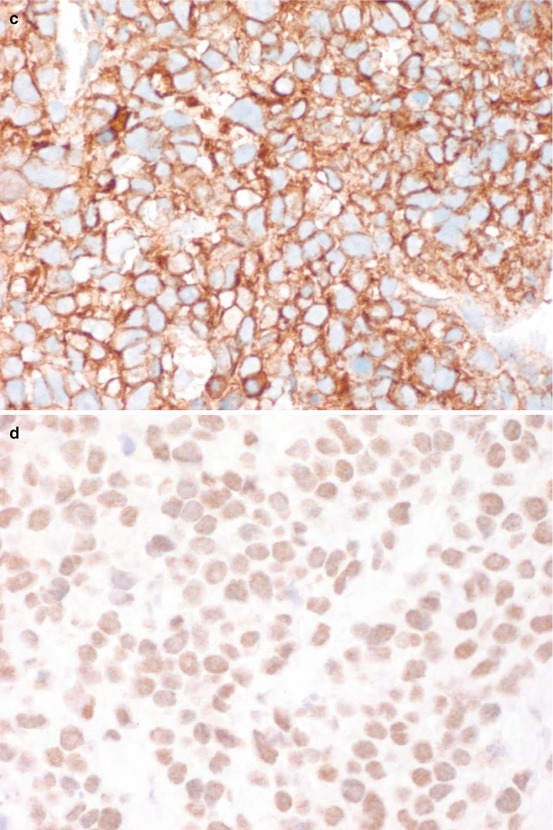

Grossly, the tumor has tan-grey cut surface with no bone or cartilaginous matrix. Necrosis and hemorrhage can be seen. In a classic Ewing sarcoma, the tumor is composed of small round cells with scant cytoplasm and round nuclei arranged in a vaguely lobular pattern or completely dyscohesive. This latter appearance resembles lymphoma. However, the cytoplasm of Ewing sarcoma appears clear and contains glycogen, which stains positively with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS). Ewing sarcoma also lacks the lymphoglandular bodies which represent cytoplasmic debris of lymphoma cells. In an atypical Ewing sarcoma, the tumor cells are larger with more pleomorphic nuclei and prominent nucleoli [3]. Neuroectodermal differentiation can be seen with tumor cells forming rosette-like structures. Immunohistochemical stain pattern of Ewing sarcoma includes positive vimentin, CD99 (membranous staining pattern), Keratin (aberrantly expressed in 30% cases), neuroendocrine markers, FLI-1 and, rarely, ERG) [13, 21, 22]. A histological, immunohistochemical and molecular illustration of Ewing sarcoma is in Fig. 7.5.

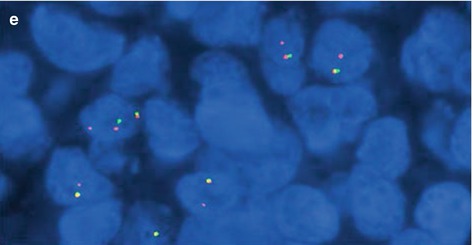

Fig. 7.5

Ewing sarcoma. (a) HE ×200. (b) HE ×400. (c) CD99+ ×400. (d) FLI1+ ×400. (e) FISH ×1000 showing LSI EWSR1 (22q12) break-apart probe showing EWSR1 rearrangement

7.1.4 Osteosarcoma

Patients with primary lumbosacral osteosarcoma are older at presentation and commonly males [20]. Secondary sacral osteosarcoma occurs in patients with previous radiation treatment or a history of Paget’s disease. Elderly patients with polyostotic Paget’s disease are most at risk for sarcomatous degeneration [2].

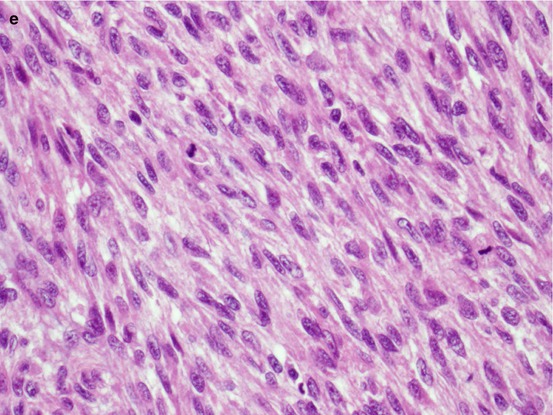

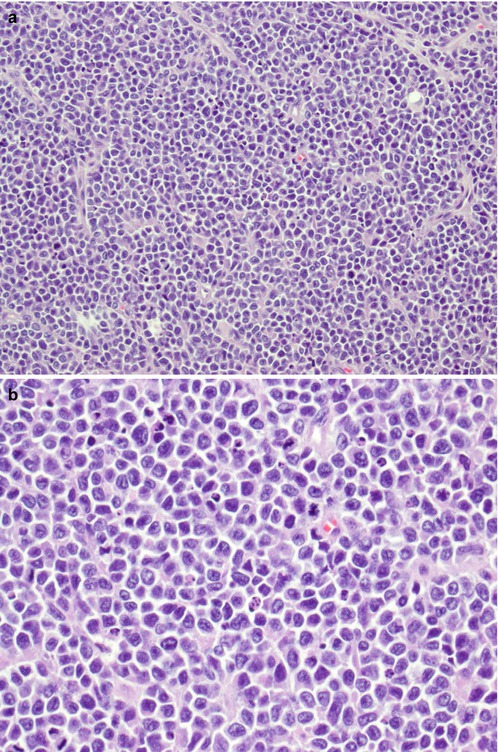

According to its location in the bone, central osteosarcoma is located in the medullary cavity, and peripheral osteosarcoma arises from the surface of the bone [23]. The characteristic of primary central osteosarcoma and surface osteosarcoma are summarized in Tables 7.3 and 7.4. Surface/peripheral osteosarcoma very rarely affects the flat bone.

Table 7.3

Characteristics of histological variants of primary central osteosarcoma

Tumor type | Component | Prognosis |

|---|---|---|

Conventional | High-grade sarcoma with osteoid formation | High-grade tumor. Subtype does not differ in prognosis and therapy |

Osteoblastic (76–80%) (Fig. 7.6a) | ||

Chondroblastic (10–13%) (Fig. 7.6b) | ||

Fibroblastic (10%) | ||

Telangiectatic | High-grade osteosarcoma with characteristic blood lakes and spaces | Similar to conventional type |

Giant cell rich | High-grade osteosarcoma with abundant osteoclast-like giant cells (Fig. 7.6c) | Similar to conventional type |

Small cell | High-grade osteosarcoma with characteristic small tumor cells (Fig. 7.6d) | Slightly worse prognosis than conventional type |

Low-grade central | Low-grade osteosarcoma | Excellent prognosis |

Note: Distinguish from fibrous dysplasia by permeation of the host bone and soft tissue extension; amplification of MDM2 gene |

Table 7.4

Characteristics of histological variants of primary peripheral osteosarcoma

Tumor type | Component | Prognosis |

|---|---|---|

Parosteal (Juxtacortical osteosarcoma) | Low-grade | Excellent |

Spindle cells with mild to moderate atypia, well-formed bone trabeculae arranged in parallel pattern, and associated benign cartilaginous differentiation | ||

Note: Amplification of MDM2 gene | ||

Periosteal (Juxtacortical chondroblastic osteosarcoma) | Intermediate-grade | Better prognosis than conventional osteosarcoma |

Predominantly atypical cartilage admixed with intermediate-grade osteosarcoma | ||

High-grade surface osteosarcoma | High-grade osteosarcoma of the surface | Similar to conventional type

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|