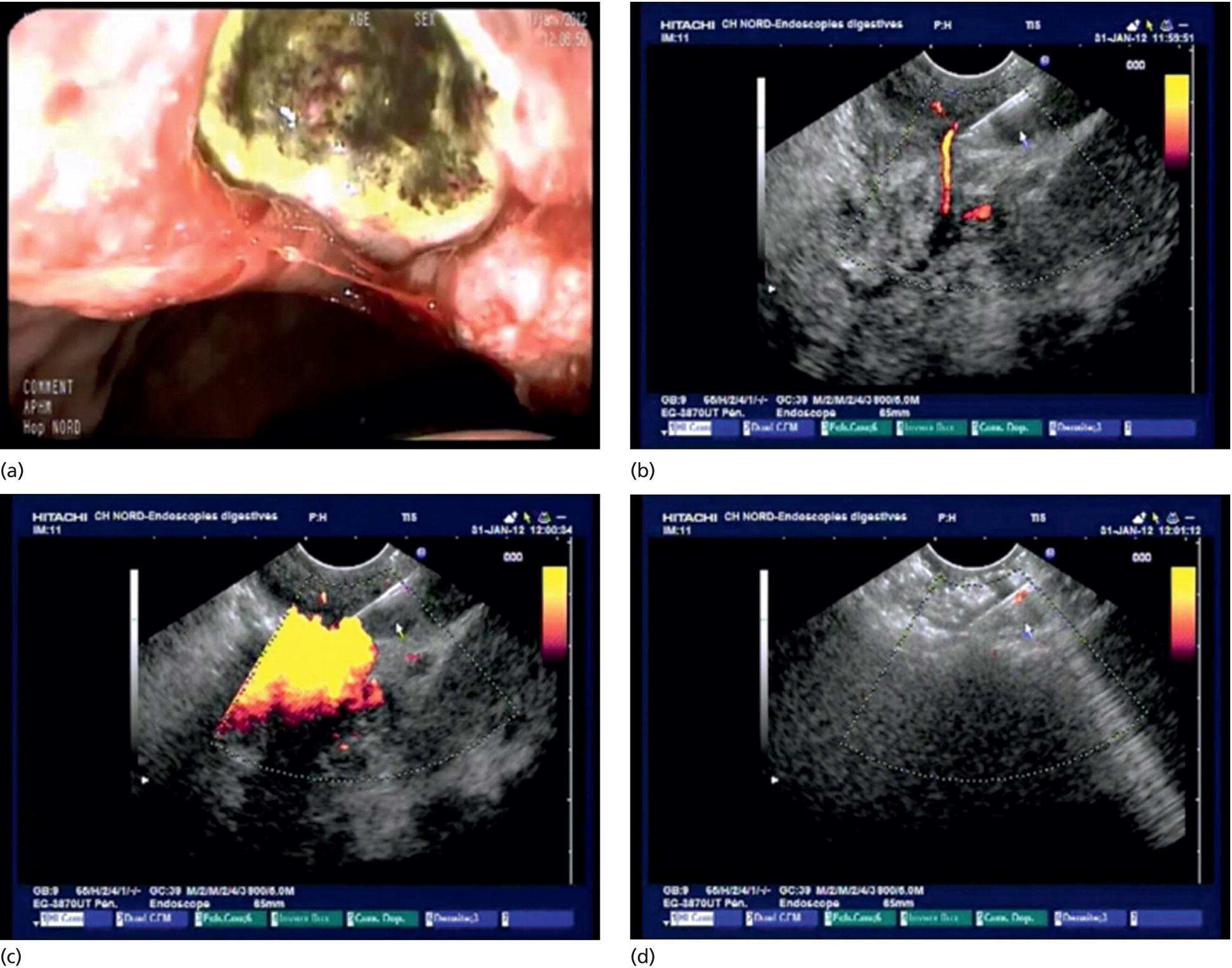

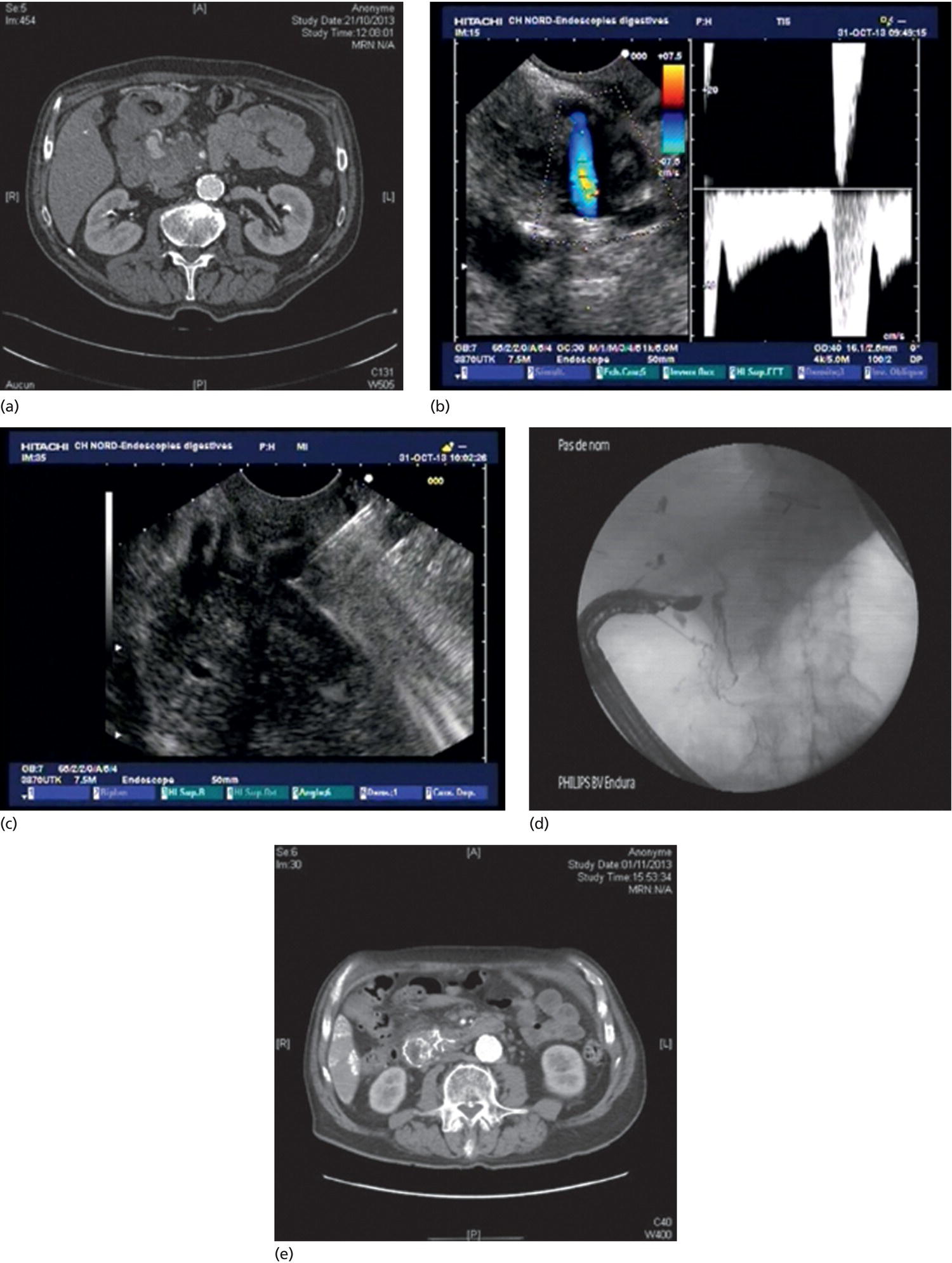

Marc Barthet and Jean‐Michel Gonzalez Digestive endoscopy and gastroenterology department, North Hospital, Marseille, France Recent developments in therapeutic endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) have opened up new fields and EUS‐guided sclerotherapy and embolization for gastrointestinal bleeding represents a possible new therapeutic approach [1–3]. In approximately 10–15% of cases, conventional endoscopy is insufficient and leads to early recurrence of bleeding [4]. To date, a limited number of human studies with small patient cohorts [1–3] have been reported in the literature, with 13 series including at least 242 patients having been published [3]. Nevertheless, the effectiveness and possible complications of the EUS‐guided vascular approach in the treatment of refractory gastrointestinal bleeding have been poorly assessed in the literature [5–15]. Most of the cases with recurrent bleeding of gastric or peri‐anastomotic varices have been treated with injection of polidocanol or cyanoacrylate, with a satisfactory final success rate [8,11,13,15]. More recently, EUS‐guided vascular embolization with microcoils has been advocated as decreasing the risk of pulmonary embolism [12,15]. Some rare cases of ulcerations or ulcerations related to a gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) have also been treated using this approach [5,8,14]. Three cases of pseudoaneurysm treated with injection of cyanoacrylate under EUS guidance have been reported, with success in all cases [8,13,14]. The potential limitations of this new application of therapeutic EUS are numerous [1–3,5–15] and include the limited visual field of the scope, the risk of damaging the operating channel, and the risk of induced infections and pulmonary embolism. All procedures were performed on hemodynamically stable patients who received systemic antibiotic prophylaxis (2 g of amoxicillin and clavulanate) 30 minutes before the procedure. Proton pump inhibitor infusion was administered over one week. Patients were maintained under general anesthesia in the operating room, with X‐ray control. Following conventional endoscopy, a linear endoscope with a large working channel (3.8 mm; Pentax UTK, Japan) with Doppler‐enhanced EUS was used. The procedure involved the puncture of the target vessel with a 19‐gauge needle (EchoTip; Cook, Winston Salem, NC), followed by the injection of a combination of cyanoacrylate and Lipiodol (2 ml) under direct visualization. The combination of cyanoacrylate glue and Lipiodol was used in both patients since microcoil embolization was not available in our hospital. Doppler monitoring was performed at the end of the procedure to ensure the disappearance of the Doppler signal. The first patient (Figure 43.1) was an 83‐year‐old man presenting with recurrent hematemesis and melena. Endoscopy showed a huge gastric cancer located to the lesser curve and computed tomography (CT) showed multiple liver metastases. The lesion was a large, deeply excavated ulcer measuring at least 3 cm. He underwent two attempts of conventional hemostatic endoscopic treatment with either coagulation or clips. As he was unfit for surgery, it was decided to perform EUS‐guided vascular treatment. After endoscopic assessment of the tumor ulceration directly with the EUS scope, the gastric lumen was suctioned until all the air was completely removed (Video 43.1). EUS assessment was cautiously performed until the feeding artery of the tumor could be observed. The vessel was targeted with a 19G needle under Doppler control. The combination of Lipiodol (1 ml) and cyanoacrylate (1 ml) was injected directly into the vessel, followed by injection of 2 ml of pure Lipiodol to rinse the content of the 19G needle. Complete disappearence of the Doppler signal was checked at the end of the procedure. Figure 43.1 Patient 1 with refractory bleeding due to gastric cancer. (a) Bleeding gastric cancer to the lesser curve. (b) Feeding artery with 19G needle in close contact. (c) Injection of combination of Lipiodol and cyanoacrylate glue. (d) Disappearence of the Doppler signal. The second patient (Figure 43.2) was a 48‐year‐old man with early alcoholic chronic pancreatitis without calcifications. It was his second attack of acute pancreatitis, diagnosed as necrotizing acute pancreatitis. The patient was hospitalized in the intensive care unit and at day 4, a massive bleeding occurred. At endoscopy, no mucosal lesion could be demonstrated but CT scan showed a pseudoaneurysm located to the head of the pancreas. Once haemodynamic stability was achieved, EUS‐guided vascular treatment was indicated. EUS located the pseudoaneurysm in the head of the pancreas (Video 43.2). The pancreatic artery within the pseudoaneurysm was targeted with ultrasound and Doppler and a 19G needle was advanced cautiously into the artery lumen. The mixture of Lipiodol and cyanoacrylate glue was injected, followed by 2 ml of pure Lipiodol. X‐ray control showed partial reflux in the gastroduodenal artery and then the hepatic artery but without any clinical or biological consequences. Patients were allowed to eat again from three days after the procedure. Clinical and laboratory evaluations were performed daily for one week, with CT scans performed within the first week post procedure. CT scan in the second patient showed complete occlusion of the pseudoaneurysm, highlighted by the Lipiodol injection. Figure 43.2 Patient 2 with bleeding pseudoaneurysm located to the pancreatic head. (a) CT scan of the pseudoaneurysm in the pancreatic head. (b) EUS view with Doppler. (c) Insertion of 19G needle inside the pseudoaneurysm. (d) Injection of combination of Lipiodol and cyanoacrylate glue under X‐ray control. (e) Postoperative CT scan showing efficient embolization of the pseudoaneurysm. No recurrence of bleeding occurred during the follow‐up of these patients. No infection nor liver damage occurred based on clinical and biological examinations. There were few complications in most of the series, in which the patients received antibiotic prophylaxis [1–3,5–15]. At the time of each intervention, the target vessel was identified using color Doppler ultrasound and then punctured with a 19G needle. In all the procedures, it was possible to inject the embolization agent without damage to the EUS equipment. We observed that if the loss of Doppler signal within the target vessel could be confirmed at the end of the procedure, there was no recurrence of hemorrhage, as shown in seven of our eight patients [1]. The absence of a Doppler ultrasound signal after endoscopic treatment of bleeding ulcers has previously been associated with a low risk of rebleeding [1,16].

43

How to do EUS‐guided Arterial Embolization

Background

Technique

Technical illustration in two cases

Postprocedural management and complications

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree