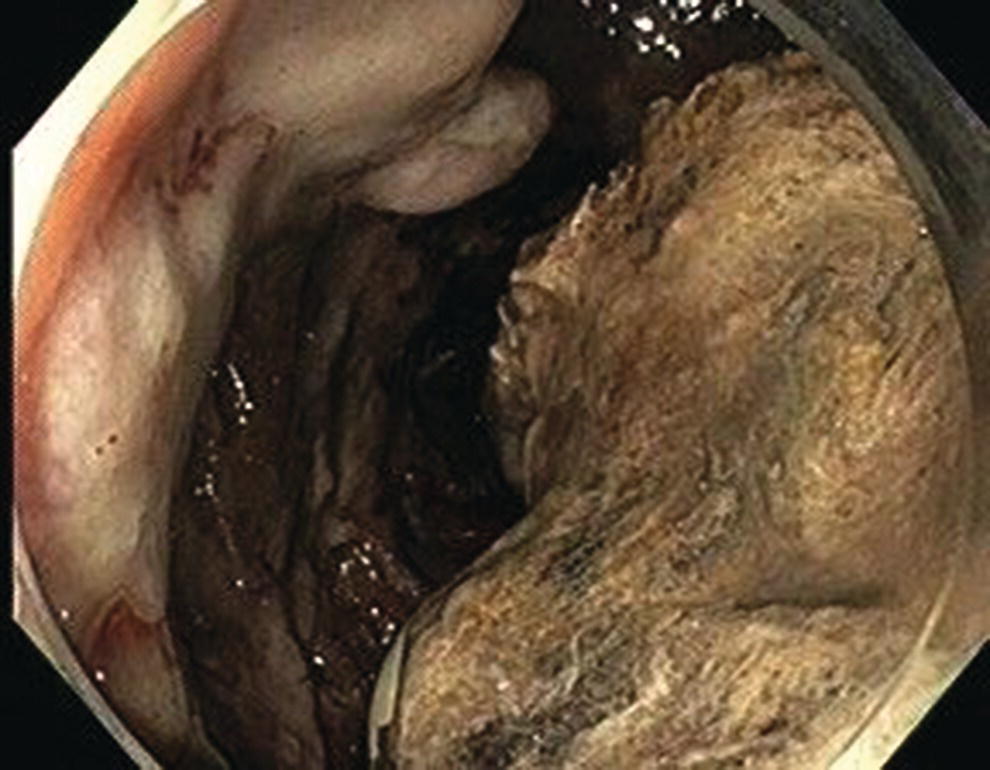

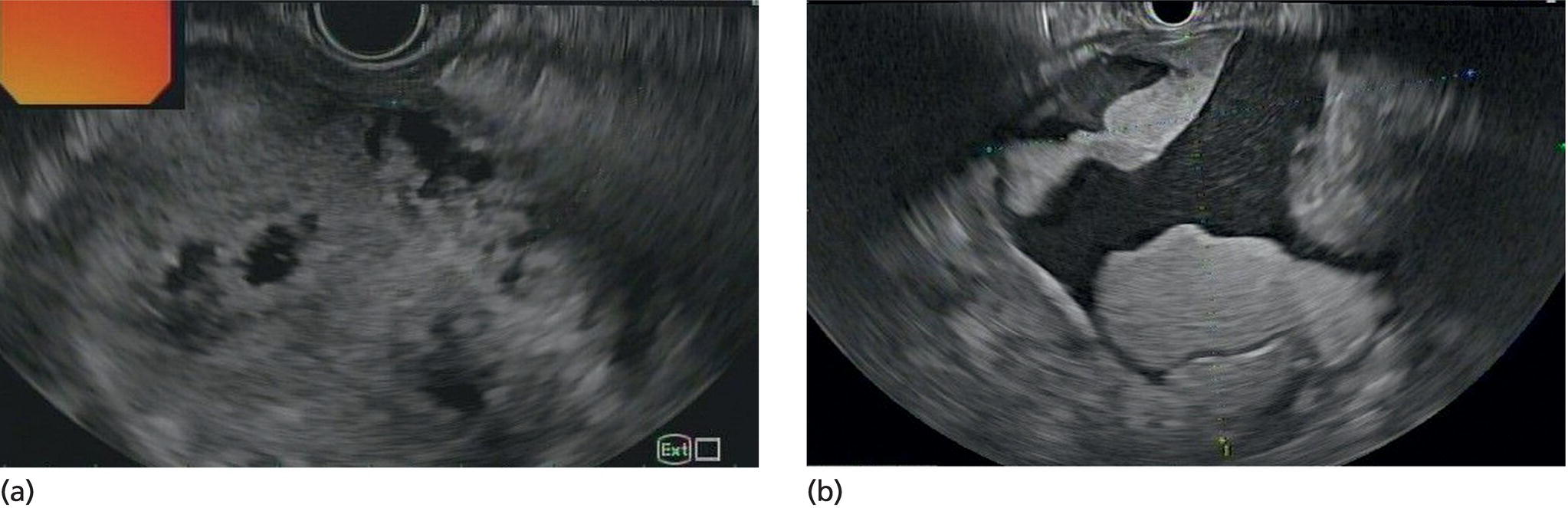

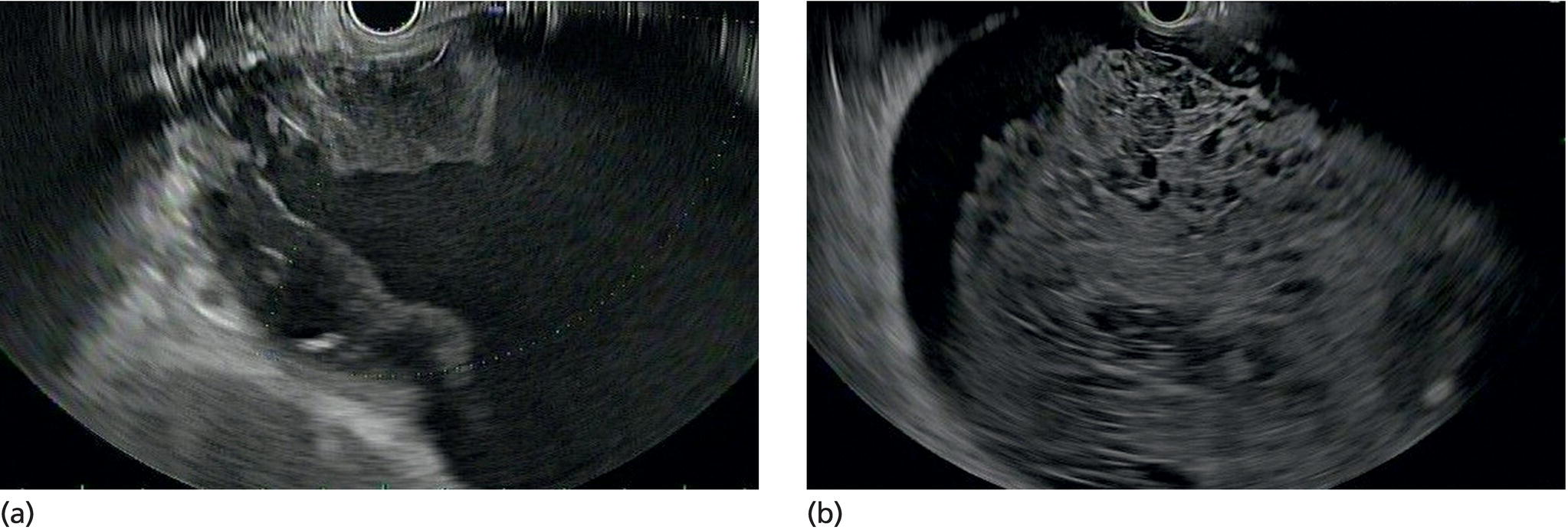

Wilson T. Kwong University of California San Diego Health Sciences, La Jolla, CA, USA Endoscopic management of necrotizing pancreatitis is now first‐line management in centers with the appropriate expertise. Minimally invasive approaches to treating necrotizing pancreatitis including percutaneous and endoscopic drainage have a lower mortality compared to open surgical necrosectomy [1,2]. Randomized controlled trials have recently demonstrated similar outcomes between surgical step‐up therapy with percutaneous drainage and endoscopic drainage followed by endoscopic necrosectomy, with fewer adverse effects including lower rates of fistula with the endoscopic approach [3]. Published series report success rates for endoscopic necrosectomy of 84–91% in resolving walled‐off pancreatic necrosis [4–6]. Endoscopic necrosectomy requires the creation of a cystgastrostomy or cystenterostomy to access a walled‐off pancreatic collection. A gastroscope is then inserted directly into the walled‐off necrosis and necrotic debris is subsequently debrided and removed from the necrotic collection. Endoscopic necrosectomy is indicated when patients have persistent sepsis despite cystgastrostomy/cystenterostomy or percutaneous drainage and antibiotics. Patient who have failure to thrive, weight loss, or persistent abdominal pain despite drainage may also benefit from endoscopic necrosectomy. However, in patients improving after endoscopic or percutaneous drainage, endoscopic necrosectomy is not mandatory and may not be necessary. Based on prospective trials, necrosectomy will be necessary in about two‐thirds of patients after initial drainage [3]. Prior to endoscopic drainage and subsequent necrosectomy, a thorough preoperative assessment should be performed. Checking for coagulopathy with international normalized ratio (INR) should be performed and corrected with vitamin K and fresh frozen plasma as appropriate. Anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents with the exception of aspirin should be ideally held as endoscopic drainage and necrosectomy are high risk for bleeding. Contrast‐enhanced computed tomography (CT) with arterial and venous phases should be performed to evaluate for pseudoaneurysms and varices which can form secondary to portal and splenic vein thromboses. Pseudoaneurysms should be embolized prior to necrosectomy. Perigastric and abdominal varices are not an absolute contraindication to necrosectomy but great care should be taken to avoid these vessels and the operator should have sufficient experience to recognize these vessels during the procedure (Figure 53.1). The CT scan should be reviewed by the endoscopist to assess the optimal site for drainage, assess if multiple sites of drainage should be performed for walled‐off collections that may not communicate, and ensure the collections are sufficiently close enough for drainage, ideally 10 mm or less from the chosen site of drainage in the upper gastrointestinal tract. Figure 53.1 There is a perigastric varix present within the wall of a necrotic collection (top left of image). Evaluation of walled‐off pancreatic necrosis is preferably imaged with a linear echoendoscope as this is the scope that will be used to perform endoscopic drainage. Collections in the lesser sac will be visible from the stomach while necrotic collections in the right lower quadrant may be visualized from the first, second, or third portions of the duodenum. Walled‐off necroses are generally heterogeneous collections consisting of anechoic fluid portions mixed with hyperechoic or isoechoic irregular solid debris of varying sizes (Figure 53.2). Collections with a large amount of solid debris may have extensive shadowing that may prevent ultrasound visualization of deeper portions of the necrotic collection beyond the debris. Blood products and clot within the collection can have a similar appearance to necrosis and cannot be reliably distinguished from necrosis alone based on endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) appearance (Figure 53.3). If clinical suspicion is high for hemorrhage into the collection, EUS aspiration of the collection immediately prior to drainage can be performed to assess for blood. Doppler ultrasound should also be performed around the collection to assess for any vessels within the gastric or duodenal wall and also varices or vessels surrounding the collection. If there are varices or large vessels around the collection, one should try to select a site of drainage further away from these vessels if possible and proceed with necrosectomy with greater caution. Figure 53.2 (a, b) Hyperechoic and isoechoic solid necrosis within necrotic collections. Figure 53.3 (a, b) Clots and blood products within a peripancreatic collection which can have similar appearance to solid necrosis.

53

How to do Endoscopic Necrosectomy

Introduction

Preprocedure assessment

EUS evaluation of walled‐off pancreatic necrosis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree