Etiology

Since the recognition of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection as the cause of acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) in the 1980s, many changes have occurred in the demographics, complications, and treatment of this disease. AIDS is the most advanced stage of HIV infection, where patients have a CD4 count of less than 200 cells/mm 3 or an AIDS-defining condition, such as recurrent bacterial pneumonia, Kaposi sarcoma (KS), or Pneumocystis jirovecii . Pneumonia. The introduction of antiretroviral therapy (ART) has been associated with a dramatic reduction in HIV-associated morbidity and mortality. Despite such progress, pulmonary disorders, including respiratory infections, malignancies, and inflammatory conditions, remain a source of significant morbidity and mortality among HIV-infected individuals throughout the world. Compounding this fact is that access to ART and treatment for specific conditions, especially among resource-poor individuals in the developed and underdeveloped world, remains a problem.

The most common modes of infection with HIV-1 (the most common phenotype) and HIV-2 are sexual transmission at the genital or colorectal mucosa, exposure to infected blood or blood products, transmission from mother to infant, and, occasionally, accidental occupational exposure. Infection is initiated by the binding of the virion gp120Env protein to the CD4 molecule found on some T cells, macrophages, and microglial cells. Reverse transcription occurs, yielding a strand of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) from the viral ribonucleic acid (RNA). Double-stranded DNA forms and integrates into the genome of the cell, enabling virus production. Genes on the newly formed DNA direct production of protease, reverse transcriptase, and other proteins that are variably targeted by ARTs.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

According to the United Nations AIDS fact sheet, the number of people living with HIV or AIDS worldwide was estimated to be 36.7 million in 2016, with about 1.8 million people becoming newly infected. New HIV infections among children and adults have decreased worldwide by 47% and 11%, respectively, since 2010 and have declined in most regions except Eastern Europe and Central Asia. Around half of all people living with HIV have access to treatment. AIDS-related deaths have decreased by 48% around the globe since 2005 with improved therapies. There are significant differences in the epidemiology of HIV infection around the world. In eastern and southern Africa, women and girls account for 59% of those living with HIV infection. This region also accounts for 43% of new worldwide HIV infections. Western and central African women also account for more than half of the HIV-infected population, whereas in other regions of the world, men are more commonly affected. In the United States the majority of newly diagnosed HIV infections were attributed to men having sex with men and intravenous (IV) drug use.

Overall, the majority of HIV-infected patients progress to AIDS within the first decade of diagnosis. The majority of the patients who do not receive ART die within 2 years of the onset of AIDS, whereas those who receive ART survive more than 10 years.

Clinical Presentation

Infection with HIV may result in varied clinical manifestations, ranging from asymptomatic carriage, to various organ system manifestations, to severe opportunistic disease. HIV most severely cripples an individual’s cell-mediated immunity, leading to a wide range of infections with typical transmissible infectious agents and opportunistic pathogens and certain malignancies that rarely cause illness in immunocompetent individuals. HIV infection causes a progressive reduction in the number of functioning CD4 helper T-cell lymphocytes; in addition, it causes deficiencies in other humoral, cell-mediated, and phagocytic functions. The incidence of specific opportunistic infections varies greatly with local factors (i.e., the prevalence of certain diseases in certain geographic regions).

The World Health Organization (WHO) specifies four clinical stages of HIV infection, which range from asymptomatic individuals (stage 1) to individuals who have experienced at least one opportunistic infection or malignancy (stage 4). The CD4 count is the most widely used indicator of the degree of immunosuppression and relates directly to the complications that occur. An important threshold is a CD4 count less than 200 cells/mm 3 , which is considered an AIDS-defining event for an HIV-infected individual, even in the absence of an AIDS-defining illness, and places the patient at risk for opportunistic infections and certain malignancies. Patients with a CD4 count greater than 200 cells/mm 3 may develop bacterial pneumonia, tuberculosis (TB), and lung cancer, but most of the classic complications of AIDS (e.g., Pneumocystis pneumonia, disseminated fungemia, KS, and AIDS-related lymphoma) occur with CD4 counts less than 200 cells/mm 3 and usually less than 100 cells/mm 3 . There are few generalities regarding clinical presentation to indicate the etiology of complications in HIV patients. In contrast to most malignancies, except lymphoma, pulmonary infections typically manifest with fever. Among various infections, bacterial pneumonia often is associated with an acute onset of fever, pleuritic chest pain, productive cough, and purulent sputum. In contrast, Pneumocystis pneumonia typically has a more insidious onset, with symptoms present for more than 1 week before the individual presents to medical attention with symptoms of dyspnea and dry cough. In contrast to bacterial pneumonia, pleuritic chest pain is usually absent in patients with Pneumocystis pneumonia, unless it has been complicated by a pneumothorax.

Manifestations of the Disease

Infection

Bacterial Respiratory Infection

General.

Bacterial respiratory infections, including infectious airways disease and pneumonia, are currently the most common respiratory diseases in HIV-infected individuals in developed countries. HIV infection is associated with a 10-fold to 25-fold increased incidence of bacterial pneumonia over that in the general community. The significance of bacterial pneumonia in HIV infection is underscored by the inclusion of severe bacterial pneumonia as a stage 3 disease by the WHO and recurrent bacterial pneumonia as an AIDS-defining illness for an HIV-infected individual, regardless of the CD4 cell count.

Although HIV infection is most closely associated with alterations in cell-mediated immunity, humoral immunity is also impaired, particularly in advanced stages. Altered B-cell function and defects in neutrophil function, which are especially prevalent among HIV-infected children, place HIV-infected individuals at high risk for frequent infections with encapsulated bacteria. A specific causative agent can be identified in approximately 40% to 75% of HIV-infected adults with bacterial pneumonia. Streptococcus pneumoniae is the most common bacterial cause of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) among HIV-infected adults, causing approximately 20% of all bacterial pneumonias. Other common infectious agents include Haemophilus influenzae, Staphylococcus aureus, Legionella pneumophila, and Klebsiella pneumoniae . HIV-infected patients are at increased risk for developing infectious airways disease, such as bacterial tracheobronchitis and bronchiolitis. The most common bacterial organisms responsible for infectious airways disease in AIDS are the same ones that cause frank pneumonia, and the clinical presentation is similar.

AIDS patients with advanced immunosuppression also are vulnerable to unusual pulmonary infections, including Nocardia asteroides, Rhodococcus equi, Bartonella henselae, and Bartonella quintana. The lung is the most commonly involved organ in HIV-related nocardiosis. Patients with nocardial pulmonary infection are typically in an advanced stage of immunosuppression, with CD4 counts usually less than 100 cells/mm 3 . A severely immunosuppressed patient may succumb to, or with, Nocardia infection. R. equi, an endemic infection in horses, manifests in AIDS patients with an indolent course of cough, fever, and dyspnea. Bacillary angiomatosis, an infection caused by B. henselae and B. quintana, is characterized by a neovascular proliferation involving multiple sites in the body, including skin, liver, spleen, lymph nodes, and lung. Exposure to cats, cat fleas, and lice is the main risk factor for this infection. Affected patients typically present with angiomatous skin lesions that mimic KS. Clinical symptoms include fever, night sweats, cough, and occasional hemoptysis.

Although bacterial pneumonia often occurs earlier in the course of HIV than do other opportunistic infections, the most consistent risk factor for bacterial pneumonia is the stage of HIV disease. HIV-infected individuals with CD4 counts less than 200 cells/mm 3 have a fivefold increase in prevalence of bacterial pneumonia, compared with HIV-infected individuals with CD4 counts greater than 500 cells/mm 3 . HIV-infected IV drug users and individuals who smoke illicit drugs (e.g., cocaine, crack, marijuana) have an increased risk of bacterial pneumonia.

HIV-infected individuals with bacterial pneumonia usually have the same signs and symptoms as HIV-free patients. Typically, such patients present with a relatively rapid onset of clinical symptoms, such as productive cough, fever, chills, pleuritic chest pain, and dyspnea. Symptoms are usually present for less than 1 week before a patient seeks medical attention. In contrast, HIV patients with most other pulmonary infections, including Pneumocystis pneumonia and tuberculosis, typically present after having symptoms for more than 1 week to a month or longer. Laboratory evaluation of HIV patients with bacterial pneumonia usually shows leukocytosis, but leukopenia can occur. Serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels are typically normal or only mildly elevated. The treatment of HIV/AIDS patients with bacterial pneumonia has the same spectrum of antibiotics used in non-HIV populations. HIV-infected individuals with uncomplicated bacterial pneumonia caused by typical pathogens usually have a clinical and radiographic response to antibiotic therapy, with a time course similar to that of normal hosts undergoing treatment for CAP. Lower CD4 cell counts have been associated with increased mortality and rate of intubation.

Radiography.

Chest radiographs in HIV patients with bacterial pneumonia commonly show focal consolidation, in either a segmental or a lobar distribution, similar to non–HIV-infected patients. HIV patients have a distinctly higher propensity, however, for multilobar and bilateral disease than immunocompetent patients ( Fig. 15.1 ). In almost half of cases of bacterial pneumonia, a radiographic pattern other than focal consolidation is observed. Bacterial infections also may manifest as solitary ( Fig. 15.2 ) or multiple lung nodules or masses. A study on the etiology of pulmonary nodules in HIV-infected patients found bacterial pneumonia to be the most common etiology, followed by tuberculosis. Cavitation is common in HIV-related bacterial lung infection. In most patients with cavitation, more than one pathogen was identified. S. aureus is frequently associated with septic emboli among IV drug abusers and usually manifests as multiple cavitary nodules. S. aureus CAP in non-IV drug users can also manifest as cavitary nodules or consolidation ( Fig. 15.3 ). Parapneumonic pleural effusions are seen in a significant minority of cases of bacterial pneumonia and are usually small in size. Intrathoracic lymph node enlargement is not usually evident on chest radiographs.

Chest radiographs of patients with acute bacterial bronchitis are usually normal but may show bronchial wall thickening. Extensive bronchiolitis may create reticulonodular opacities, which represent impacted bronchioles. This pattern may be symmetrically distributed, with lower lobe predominance, resembling Pneumocystis pneumonia. Radiographic manifestations of Nocardia include nodules and consolidation, which may be mass-like ( Fig. 15.4 ). There is a tendency toward upper lobe predominance. Cavitation, lymphadenopathy, and pleural effusions also may be present.

Computed Tomography.

Computed tomography (CT) may be useful in some patients with suspected bacterial pneumonia, especially when the chest radiographic findings are atypical, and when culture or serology has failed to identify an organism. CT can identify the presence of mild or subtle disease suggesting bacterial or other etiologies; characterize the distribution of that disease for further testing or therapy, such as bronchoscopy or drainage; and identify lymphadenopathy, cavitation, pleural fluid or empyema, and other differential features that may be occult on the chest radiograph. Mildly enlarged mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes are frequently seen on CT scans of patients with bacterial pneumonia, but they rarely achieve sizes of greater than 2 cm. Nodular disease may be subtle on chest radiographs and better seen by CT. CT is more sensitive and specific than radiographs in detecting bronchitis and bronchiolitis. In a patient with suspicious symptoms but a normal chest radiograph, CT may show findings of small airways disease despite the absence of radiographic findings. The characteristic findings of infectious bronchiolitis on CT consist of centrilobular and tree-in-bud opacities. Pyogenic airway infections lead to inflammatory changes involving the walls of the bronchi and bronchioles, resulting in airway wall thickening and dilation. These changes may be irreversible if not treated early with antimicrobial agents. R. equi pneumonia usually manifests with one or more foci of cavitary consolidation, often with an upper lobe predominance; additional features may include empyema and lymphadenopathy. Bacillary angiomatosis manifests as endobronchial lesions, pulmonary nodules, pleural effusions, and densely enhancing lymphadenopathy and chest wall masses.

Pneumocystis Pneumonia

General.

Pneumocystis is an opportunistic fungal pulmonary pathogen; the pathogenic form in humans is named Pneumocystis jirovecii. Since the first descriptions of profound immunodeficiency occurring in previously healthy homosexual men in 1981, the histories of AIDS and Pneumocystis pneumonia have been closely associated. It is considered an AIDS-defining condition and a WHO clinical stage 4 disease. The introduction of ART and widespread Pneumocystis pneumonia prophylaxis in industrialized nations has brought about dramatic declines in the incidence of Pneumocystis pneumonia. Despite such progress, Pneumocystis pneumonia remains one of the most common AIDS-defining opportunistic infections in the United States and Western Europe. Twenty-five percent to 33% of cases of Pneumocystis pneumonia occur in patients unaware of their HIV infection. Patients who develop Pneumocystis pneumonia almost always have CD4 counts less than 200 cells/mm 3 and often less than 100 cells/mm 3 .

Affected patients present with an insidious onset of fever, dry cough, and dyspnea. On average, symptoms are present for about 1 month before patients seek medical attention. Physical findings include tachypnea, tachycardia, and cyanosis, but lung auscultation reveals few abnormalities. Reduced arterial oxygen pressure, increased alveolar-arterial oxygen gradient, and respiratory alkalosis are evident. Decreased diffusing capacity of carbon dioxide is generally present as well. An elevated serum LDH level is highly sensitive for Pneumocystis pneumonia but is not highly specific. Serum β- d -glucan, a component of the fungal cell wall, is elevated in many patients with Pneumocystis pneumonia, in addition to other fungal processes. Because P. jirovecii cannot be grown in culture, a diagnosis is made by morphologic identification of the organism through histopathologic staining. Currently, direct fluorescent antibody stain, which detects both the cystic and trophic forms, is frequently used. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing of respiratory samples for P. jirovecii is also used where a negative result has high specificity for excluding the diagnosis. Specimens usually are obtained from induced sputum or fiberoptic bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage.

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, which acts by inhibiting folic acid synthesis, is the drug of choice for Pneumocystis pneumonia infection and prophylaxis. Pentamidine, associated with more severe toxicities, is less frequently used. Additional medications include atovaquone and dapsone. In those with moderate to severe disease, corticosteroids are given to prevent respiratory deterioration resulting from inflammatory response. Mortality ranges from 4% to 10% in recent years.

Radiography.

The classic appearance of Pneumocystis pneumonia on chest radiography is bilateral perihilar or diffuse symmetric opacities, which may be finely granular, reticular, or ground-glass in appearance ( Fig. 15.5 ). If left untreated, the parenchymal opacities may progress to airspace consolidation. Radiographic improvement usually lags at least a few days behind clinical improvement; frequent chest radiographs may be unnecessary during treatment for patients who show clinical signs of response to therapy. Advances in the prevention and treatment of Pneumocystis pneumonia have been associated with an increased frequency of unusual manifestations and a trend toward more subtle radiographic manifestations. Pneumocystis pneumonia is extremely dyspnogenic, with patients often profoundly hypoxic or symptomatic despite minimal radiographic abnormalities. A normal chest radiograph has been reported in up to 39% of cases at the time of presentation, especially in patients with severe impairment in immune status. The true frequency of normal chest radiographs in Pneumocystis pneumonia is probably closer to 10%, however.

Computed Tomography.

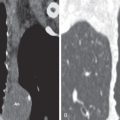

CT is more sensitive than chest radiographs for detecting Pneumocystis pneumonia and may be helpful in evaluating symptomatic patients with normal or equivocal radiographic findings. The classic CT finding in Pneumocystis pneumonia is extensive ground-glass opacity, which corresponds to the presence of intraalveolar exudate, consisting of surfactant, fibrin, cellular debris, and organisms (see Fig. 15.5 ). It is often distributed in a patchy or geographic fashion, with a predilection for the central, perihilar, and upper lungs. Pleural effusions and thoracic lymphadenopathy are rare on CT. When a tree-in-bud appearance is present on CT, Pneumocystis pneumonia infection is unlikely.

Cystic lesions are found in approximately 50% of patients ( Fig. 15.6 ). Some cysts have been shown to be secondary to tissue invasion by P. jirovecii, followed by necrosis. The presence of cysts may lead to spontaneous pneumothorax ( Fig. 15.7 ). The presence of cysts is not required, however, for pneumothorax to occur. Cysts associated with Pneumocystis pneumonia are more common in HIV-infected patients than in patients with other causes of immunosuppression. Occasionally, the cysts may resolve with therapy.

Residual interstitial fibrosis after Pneumocystis pneumonia also is common. Interstitial fibrosis also has been reported as the primary radiographic finding in a subset of patients with Pneumocystis pneumonia who experienced relatively stable symptoms over months to years. The disease of this subset has been referred to as chronic Pneumocystis pneumonia.

Fungal Infections Other Than Pneumocystis Pneumonia

General.

With the exception of Pneumocystis pneumonia, fungal organisms are relatively uncommon causes of pulmonary infection in HIV-infected patients. Nevertheless, thoracic infection from endemic and opportunistic fungi can occur. Although the most common fungal organism identified in the aerodigestive tract of AIDS patients is Candida, its presence is almost always caused by colonization, oral thrush, or esophagitis; true pulmonary infection is rare.

Most thoracic fungal infections occur in the setting of disseminated disease when the degree of immunosuppression is severe (CD4 count < 100 cells/mm 3 ). This is particularly true of the endemic fungi, including histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, and coccidioidomycosis. Of opportunistic fungi, Cryptococcus neoformans, ubiquitous in the environment, is the most common fungal pathogen to involve the lungs. More than half of patients are fungemic, and most patients have concomitant central nervous system (CNS) infection. Disseminated disease can also involve the skin, bone, and eyes in addition to the lungs. Perhaps because of relatively preserved neutrophil and granulocyte functions in AIDS, the incidence of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in patients with HIV infection was found to be only 0.1%. Drug-induced neutropenia in HIV-positive individuals, usually acquired from drugs such as zidovudine, ganciclovir, or steroids, increases the risk of disease from Aspergillus, however.

Radiography.

Fungal pulmonary infections may have varied appearances. Disseminated histoplasmosis and coccidioidomycosis commonly appear as diffuse miliary pulmonary nodules ( Fig. 15.8 ). The endemic fungal diseases also may manifest as cavities or reticulonodular opacities with or without lymphadenopathy. Cryptococcal imaging findings are often nodular or multinodular with areas of conglomeration. Foci of consolidation and reticular or reticulonodular opacities may occur. Parenchymal abnormalities may be accompanied by lymph node enlargement and pleural effusion. Patients with angioinvasive aspergillosis may show cavitary disease with an upper lobe predominance or multifocal areas of consolidation or nodules. The chest radiograph may be normal in AIDS patients with disseminated fungal infection.

Computed Tomography.

CT allows detection or better characterization of small pulmonary nodules and intrathoracic lymphadenopathy of disseminated fungal diseases (see Fig. 15.8 ). The halo sign suggestive of invasive Aspergillus infection also requires CT to be detected. Airway invasive aspergillosis manifests as tracheobronchitis, and bronchiolitis usually results in airway wall thickening and tree-in-bud opacities on CT. CT findings of various fungal infections in HIV-infected patients are similar to findings in uninfected patients, and additional details can be found in Chapter 12 .

Tuberculosis

General.

Worldwide, TB remains the leading cause of death among HIV-infected individuals, accounting for approximately one in three AIDS-related deaths. Of TB cases, 1.2 million (11% of all) occur in patients with HIV infection. TB-related deaths have decreased since 2005, but nearly 60% of TB cases among HIV-infected patients remained undiagnosed or untreated. TB remains the main pulmonary infection of HIV-infected patients in sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia. One in four HIV-infected individuals is estimated to have latent TB infection, and the development of active TB is 26-fold more likely among HIV-infected, compared to non–HIV-infected, patients. Multidrug-resistant strains of tuberculosis (MDR-TB), which originate only sporadically in the developed world, are of persistent concern in resource-poor environments. Ease of international travel is a potential mechanism by which such strains may disseminate.

TB can occur at any stage of HIV infection. Pulmonary TB is considered a WHO stage 3 disease, whereas extrapulmonary TB is classified as stage 4 disease. Reactivation (postprimary) pattern TB is often one of the initial manifestations of HIV infection. HIV-infected individuals at particularly high risk for tuberculosis include IV drug abusers and patients from areas where TB is endemic. Classic symptoms include cough, fever, night sweats, and weight loss. Symptoms are often present for more than 7 days before patients seek medical attention. The median CD4 count in HIV patients coinfected with TB is approximately 350 cells/mm 3 . In early HIV disease, skin tests are positive, and the infection is confined to the lungs. As the degree of immunosuppression becomes more severe, false-negative skin test results become more prevalent. Interferon gamma release assay blood tests, including T-Spot (Oxford Immunotec, Marlborough, MA) appear to retain sensitivity at lower CD4 counts. Because highly immunosuppressed patients may be infected with a lower colony count of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, diagnosis may be more difficult than in immunocompetent patients. The frequency of sputum smear-negative, culture-positive pulmonary TB is higher in patients with advanced immunosuppression, who often also have minimal findings on chest radiography. The WHO recommends the use of the rapid PCR test known as the Xpert MTB/RIF (resistance to rifampicin) assay (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA) as an initial diagnostic test in patients suspected to have HIV-associated TB or MDR-TB. The test is reported to be highly specific and can give a diagnosis of TB in less than 2 hours and determine rifampicin resistance. Diagnosis sometimes requires more invasive procedures, such as bronchoscopy, thoracentesis, lymph node aspiration, or pleural biopsy. In patients with miliary disease, blood cultures can be positive.

When TB is diagnosed, treatment with multiple drugs administered under direct observation is started as soon as possible. Regimens usually last longer than 6 months. The initiation of ART in the course of TB treatment is complicated by issues such as drug toxicities and interactions, treatment adherence, and immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS). Patients with low CD4 counts of less than 50 to 100 cells/µL should start ART within 2 weeks of anti-TB therapy unless there is concomitant TB meningitis, whereas those with higher CD4 counts could defer ART for 8 to 12 weeks.

Radiography.

Early in HIV infection, when the CD4 count is greater than 200 cells/mm 3 , the imaging features are typically those associated with postprimary pattern TB and include parenchymal opacities, occasionally cavitary, often located within the apical, posterior, and superior segments of the lungs ( Fig. 15.9 ). In patients with decreased CD4 counts (<200 cells/mm 3 ), findings are more typically those of primary pattern TB (regardless of the actual mechanism of infection), including middle and lower lung zone consolidation, pleural effusion, and lymph node enlargement ( Fig. 15.10 ). Progressive primary infection is common in AIDS, with diffuse lung disease, multiple pulmonary nodules, mediastinal lymphadenopathy, or miliary spread, and a lower likelihood of cavitary disease. At advanced levels of immunosuppression, 20% of HIV-positive patients with TB have normal chest radiographs. A negative chest radiograph may predict poorer outcome in AIDS patients with TB. The use of ART, with subsequent partial immune restoration, may shift the overall radiographic appearance back toward a postprimary pattern.

Computed Tomography.

On CT enlarged lymph nodes secondary to TB are easily identified, are often hypodense, and may show rim enhancement ( Fig. 15.11 ). CT in patients with TB who have a normal or near-normal chest radiograph usually reveals abnormalities, including lymph node enlargement and small or miliary nodules ( Fig. 15.12 ). Bronchitis and bronchiolitis frequently occur in HIV-positive and AIDS patients, even in patients without cavitary disease. Endobronchial spread caused by either M. tuberculosis or Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) may have identical CT appearances, typically resulting in a tree-in-bud pattern. Extrapulmonary findings, such as pleural effusion, lymphadenopathy, and pericardial effusion and thickening, are more common in HIV-infected than non–HIV-infected patients.

Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Infections

General.

In addition to TB, a wide range of mycobacterial species have been documented to infect patients with HIV/AIDS. Nontuberculous mycobacterial infections in AIDS patients are usually secondary to MAC, but identification of MAC in sputum usually signifies colonization and not true infection. Other mycobacteria that may lead to pulmonary and extrathoracic disease in AIDS include Mycobacterium kansasii, Mycobacterium fortuitum, and Mycobacterium xenopi, among others. Because MAC and other nontuberculous mycobacteria are less virulent than M. tuberculosis, they are usually encountered in the setting of more advanced immunosuppression (CD4 < 50 cells/mm 3 ). The incidence has decreased significantly after introduction of ART. In many patients the nontuberculous mycobacterial infection was disseminated, with respiratory tract involvement. However, isolated pulmonary involvement can occur, particularly with M. kansasii . Clinical characteristics are similar among AIDS patients with nontuberculous infections, including fever, cough, and weight loss occurring over weeks or months.

Prophylactic treatment with weekly azithromycin is recommended for HIV-positive patients with CD4 counts less than 50 cells/mm 3 . Therapy of nontuberculous mycobacterial infections involves prolonged multidrug regimens.

Radiography.

Imaging findings in the lungs vary if present and may include patchy consolidation ( Fig. 15.13 ), ill-defined nodules, cavities, and lymphadenopathy ( Fig. 15.14 ). Lymphadenopathy is frequently present and similar in occurrence and appearance to lymphadenopathy in AIDS patients with tuberculosis. A normal chest radiograph may be observed in 20% to 25% of patients with pulmonary infection from MAC or M. kansasii.

Computed Tomography.

As is the situation with tuberculosis, CT findings in nontuberculous mycobacterial infections may include lymphadenopathy ( Fig. 15.15 ), cavitation, and bronchiolar (tree-in-bud) opacities that are invisible on the chest radiograph.

Viral Infections

General.

Defects in cellular immunity permit many different viruses to cause pneumonia in HIV-infected patients, including respiratory syncytial virus, varicella, influenza, and human cytomegalovirus (CMV). Of these, CMV, a member of the Herpesviridae family, is the most common viral pulmonary pathogen in AIDS patients. Although it is frequently recovered from the respiratory system in vivo and at autopsies, CMV is more often an extrathoracic pathogen than a cause of clinical pneumonia. ART has substantially reduced all manifestations of CMV in AIDS patients. When present, CMV pneumonitis affects patients with advanced levels of immunosuppression (CD4 counts < 100 cells/mm 3 ). CMV infection occurs most frequently in patients infected with HIV by heterosexual or homosexual contact. CMV pneumonitis is characterized by a mixed neutrophilic and inflammatory cell infiltrate in alveolar septa and airspaces. Typical nuclear and cytoplasmic inclusions are found in cells within the inflamed tissue, the presence of which is required to confirm true infection as opposed to colonization. AIDS patients with CMV pneumonia usually present with nonspecific symptoms, such as fever, shortness of breath, and hypoxia on room air. Auscultation reveals diffuse rales, and blood tests show an elevated LDH level. Anti-CMV therapy with ganciclovir or valganciclovir is considered the treatment of choice. Ganciclovir also is used in maintenance doses to prevent future infection.

Radiography.

Chest radiography in patients with pulmonary CMV usually reveals diffuse bilateral opacities. Opacities may be of ground-glass, reticular, or alveolar pattern. These patterns are also seen in other viral pneumonias ( Fig. 15.16 ). Nodules are frequently identified; occasionally, nodules may be mass-like. Additional imaging findings include bronchiectasis and bronchial wall thickening.