Etiology

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP), also known as extrinsic allergic alveolitis, is an immune-mediated inflammatory form of diffuse interstitial pulmonary disease caused by inhalation of various antigens that affect susceptible patients. Occasionally, an HP reaction pattern may be seen in association with drug toxicity. Bacterial, mycobacterial, fungal, animal protein, and chemical compound causative antigens have been identified, with common examples listed in Table 32.1 .

| Disease | Agent | Common Source |

|---|---|---|

| Farmer’s lung | Saccharopolyspora rectivirgula, Thermoactinomyces vulgaris, Absidia corymbifera | Moldy hay, grain, silage |

| Humidifier lung | T. vulgaris | Contaminated forced-air systems; water reservoirs |

| Mushroom worker’s lung | Thermoactinomyces sacchari | Moldy mushroom compost |

| Woodworker’s lung, wood pulp worker’s lung | Alternaria tenuis , wood dust | Oak, cedar, and mahogany dust; pine and spruce pulp |

| Japanese summer-type pneumonitis | Trichosporum cutaneum (T. asahii) | Contaminated old houses (tatami mats) |

| Hot tub lung | Mycobacterium avium complex | Hot tub water |

| Metal-working fluid–associated hypersensitivity pneumonitis | Mycobacterium immunogenum | Metal-working fluids |

| Bird fancier’s lung, pigeon breeder’s disease | Avian proteins | Avian droppings, feathers (parakeets, budgerigars, pigeons, chickens, turkeys) |

| Laboratory worker’s lung | Proteins of rats, gerbils | Urine, serum, pelt proteins |

| Chemical worker’s lung | Isocyanates; trimellitic anhydride | Polyurethane foams, spray paints, finishes, sealants, special glues |

HP occurs most commonly in middle-aged adults and is more common in nonsmokers when compared to demographically matched smokers, which is suspected to be due to the immunosuppressive effects of cigarette smoke on the intrapulmonary immune mediator cells that are implicated in HP. Smokers who do develop HP are more likely to develop chronic disease, however, and have a worse prognosis than nonsmokers. Certain occupations and hobbies that involve materials harboring the causative antigens have been described in the literature and should be queried during the collection of a detailed exposure history.

The development of HP is influenced by the size, immunogenicity, duration of exposure, and number of inhaled organic particles and the immune response of the affected individual. Not all equal exposures lead to the development of HP. Farmer’s lung (one of the most common types of HP), for instance, is estimated to occur in 9% to 12% of exposed farmers, and bird fancier’s lung is estimated to occur in 15% of bird keepers. It is not yet clear which variables determine the initial presentation and clinical course of the disease. Regardless of the type of causative antigen or its environmental setting, only a small percentage of individuals with any given antigenic exposure develop HP.

The pathogenesis of HP is incompletely understood, but it is accepted that HP results from a non–immunoglobulin (Ig)E-mediated hypersensitivity reaction. The antigens associated with the development of HP usually occur in aerosolized particles of less than 3 µm in diameter, which enables their deposition in the distal airspaces, resulting in type 3 (antigen-antibody complex) and type 4 (delayed cell-mediated) hypersensitivity reactions. There is also evidence that alterations in neutrophil chemotaxis are involved in the pathophysiology of HP.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

The prevalence and incidence of HP in the general population are difficult to evaluate, as disease manifestation is influenced by climatic, seasonal, and geographic conditions; differing diagnoses of the disease; methods to establish the diagnosis; intensity of exposure; smoking habits; and genetic risk factors.

Clinical Presentation

Traditionally, HP has been described in terms of acute, subacute, and chronic manifestations. Although this classification has merits, there is significant clinical overlap of these stages, and many patients present with findings not purely conforming to one category.

An alternative classification scheme described in a 2011 publication by Lacasse and coworkers sorted patients into clusters on the basis of clinical presentation, physical examination, laboratory results, chest radiograph findings, computed tomography (CT) findings, and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) results. This cluster system found that HP patients were most effectively grouped into two clusters. Cluster 1 patients had more recurrent systemic symptoms and fewer abnormal chest radiographs than those in cluster 2. Cluster 2 patients also had more severe restrictive lung disease patterns on pulmonary function testing and more pronounced fibrotic changes on CT. Although this classification scheme may best fit the HP patient population, the acute, subacute, and chronic subgroups persist in the literature and will be maintained throughout this chapter.

Acute HP manifests with abrupt onset of symptoms within 2 to 9 hours of antigenic exposure in a previously sensitized patient. Influenza-like symptoms often predominate, including chills, fever, myalgia, headache, and nausea. Respiratory symptoms range from mild cough to severe dyspnea and occasionally may progress to respiratory failure. Symptoms gradually decrease within hours or days of exposure cessation but may recur after reexposure.

Subacute HP can be triggered by continuous exposure to antigen or repeated acute exposure. Symptoms may appear gradually over a period of several days to weeks. Patients usually present with milder symptoms compared with acute HP, often experiencing exertional dyspnea and cough with or without fever. Numerous exacerbations and remissions of subacute HP over an extended time may be seen in patients with subacute HP.

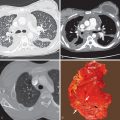

Chronic HP can develop as a progression from acute or subacute HP or may occur without any preceding HP history. Cough and exertional dyspnea are common initial manifestations, and fatigue and weight loss may be quite severe. Bilateral crackles are commonly present on auscultation, and digital clubbing may occur. Chronic HP may progress either to emphysematous or fibrotic end-stage forms, which confer a worse prognosis ( Figs. 32.1 and 32.2 ). Pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, and subcutaneous air are rare manifestations of HP.

Diagnosis

Nonspecific clinical presentation and variable occurrence in exposed individuals require that physicians maintain a high index of suspicion and collect a meticulous history in making the diagnosis of HP. In up to 40% of histologically proven cases of HP, the offending agent is not identified. In most cases, however, the diagnosis of HP can be made based on a combination of history of exposure to a possible allergen, clinical features, lung function tests, and consistent radiologic findings. The 2003 HP Study, a prospective multicenter study, identified factors that had significant predictive power in identifying active HP. These included known exposure to an offending antigen, onset of symptoms within 8 hours after exposure, the presence of precipitating antibodies, and the presence of inspiratory phase crackles on physical examination.

Laboratory Findings

Laboratory testing in HP may include hematologic assessment, pulmonary function testing, testing for serum precipitins (precipitating antigens) to common causative antigens, specific inhalation challenge, BAL, and lung biopsy.

Hematologic evaluation in HP may reveal slight to moderate neutrophilic leukocytosis with lymphopenia, particularly during acute and subacute episodes. Nonspecific markers of inflammation, such as C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, may be elevated. Serum precipitating antibodies against the offending antigens may be present, and although these IgG antibodies are excellent markers of exposure to specific antigens in the environment, they are considered confirmatory evidence rather than pathognomonic for HP, and their absence does not exclude the diagnosis of HP. Numerous studies have documented the presence of serum precipitins in asymptomatic individuals with exposure to certain antigens, and conversely, the absence of serum precipitins in patients with HP has also been documented.

BAL in active HP may show heightened overall cellularity, as well as an elevated proportion of lymphocytes. Notably, during an acute exacerbation, the proportion of neutrophils may be higher than that of lymphocytes. Specific inhalation challenge (SIC) tests involve nebulized antigenic exposure in a controlled clinical setting under medical supervision, with pulmonary function testing performed at multiple time points during the examination. SIC examinations are of questionable clinical utility in confirmation of HP diagnosis and may at best provide confirmatory evidence.

Lung Function

Functional abnormalities in HP include a reduction in the carbon monoxide diffusing capacity, predominantly restrictive lung function with a reduction of total lung capacity and forced vital capacity, and resting hypoxemia that usually worsens during exercise. Although restrictive lung function is the most commonly described long-term outcome in patients who have chronic HP, obstructive pattern findings are identified in some patients.

Pathologic Findings

Classic histologic findings of HP have been described, regardless of the type of inciting antigen. The histologic patterns of HP vary with the stage of disease and may mimic the patterns of other interstitial lung diseases.

Information about the lung biopsy findings of acute HP is limited, as biopsy is rarely performed. Histologic abnormalities described in these patients are nonspecific and include neutrophilic infiltration of the airspace and respiratory bronchioles combined with interstitial pneumonia, acute vasculitis, organizing pneumonia, and a pattern of diffuse alveolar damage.

Subacute HP is characterized by a triad of cellular bronchiolitis; chronic bronchiolocentric cellular interstitial pneumonia composed predominantly of lymphocytes; and scattered, small, poorly formed noncaseating granulomas ( Fig. 32.3 ). Only approximately 60% of patients have all three findings at biopsy, however. In patients with only cellular interstitial pneumonia, the histologic features can be identical to the features of nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP). Other abnormalities that may be seen include areas of organizing pneumonia and constrictive bronchiolitis (or obliterative bronchiolitis) characterized by smooth muscle hypertrophy, peribronchiolar fibrosis, and partial airway obstruction.

Histologically, the chronic stage of HP often shows fibrosis superimposed upon findings of subacute HP. NSIP pattern and usual interstitial pneumonia pattern are histologic features of chronic HP and may be the predominant or the only histologic finding.

Manifestations of the Disease

Radiography

HP may yield a radiograph with no significant abnormalities, and its only utility may be in excluding other differential considerations. For instance, in a study of patients with bird breeder’s lung and abnormal high-resolution CT, 7 (33%) of 21 patients with subacute HP and 1 (4%) of 24 patients with chronic HP had normal chest radiographs. If abnormalities are present, acute HP most commonly manifests with middle or upper lung zone–predominant nodular or reticulonodular opacities ( Fig. 32.4 ).

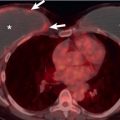

The radiographic features of subacute HP include hazy areas of increased opacity (ground-glass opacities) ( Fig. 32.5 ) and poorly defined nodular opacities ( Fig. 32.6 ). Although an upper lung zone predominance is commonly seen in other forms of HP, subacute HP has a more variable geographic pattern, and a diffuse or even lower lung zone predominance may be seen. Diffuse consolidation is rare in patients with subacute HP, and when present, superimposed infection should be considered ( Fig. 32.7 ). Pneumomediastinum, pneumothorax, and subcutaneous air may be seen in some patients, presumably resulting from overdistention or disruption of alveoli with obliteration of the respiratory bronchioles ( Fig. 32.8 ).

The radiographic manifestations of chronic HP may include reticular opacities, honeycombing, and volume loss ( Fig. 32.9 ). The fibrosis may be diffuse and severe in all lung zones or have an upper or middle lung zone predominance. Hilar and mediastinal lymph node enlargement may be seen and is a nonspecific finding ( Fig. 32.10 ).

Computed Tomography

A multicenter study by Lacasse and coworkers showed that the diagnosis of HP often can be made or rejected with confidence based on clinical history and high-resolution CT findings without the need for bronchoscopy or biopsy. Transbronchial biopsy and surgical biopsy are generally considered for patients in whom bronchoalveolar lavage and high-resolution CT fail to yield a confident diagnosis. High-resolution CT frequently shows characteristic findings in patients with normal or nonspecific chest radiographs ( Fig. 32.11 ).

Acute Phase

Because of the milder clinical manifestations and often rapid resolution of the symptoms, high-resolution CT is uncommonly performed in the assessment of patients with acute HP. CT in acute HP may be completely unremarkable. When abnormalities are present, the most common high-resolution CT findings consist of diffuse ground-glass opacities and consolidation. Centrilobular nodules also may be seen. The diffuse airspace opacification seen in acute HP may be due to diffuse alveolar damage or acute organizing pneumonia.

Subacute Phase

High-resolution CT in subacute HP may show poorly defined small centrilobular nodules ( Fig. 32.12 ), symmetric patchy or diffuse bilateral ground-glass opacities, and lobular areas of decreased attenuation and vascularity on inspiratory images (mosaic attenuation) and air-trapping on expiratory images ( Figs. 32.13 and 32.14 ). a

a References .

Imaging abnormalities in subacute HP may show a diffuse distribution, an upper lung zone predominance, or may even show a middle and lower lung zone predominance with sparing of the bases.