Functions

• General somatic efferent (GSE). Somatic motor to all the intrinsic muscles of the tongue (longitudinal, transverse, and vertical muscle bundles) and all of the extrinsic muscles of the tongue (hyoglossus, genioglossus, styloglossus) except palatoglossus (innervated by cranial nerve [CN] X).

Anatomy

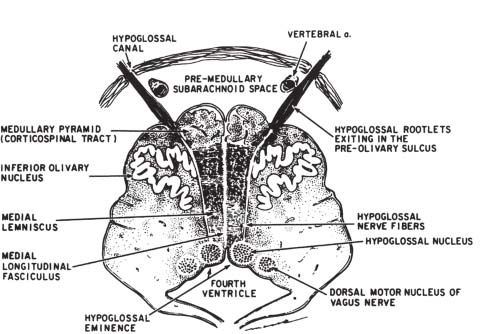

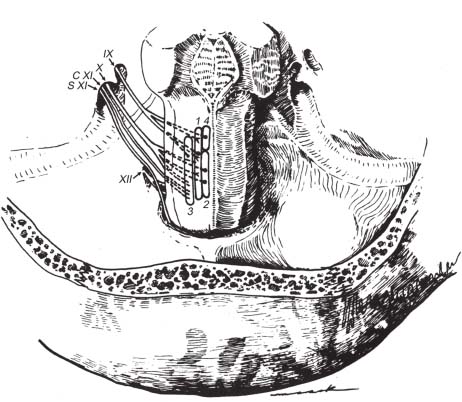

• Fibers arise from the hypoglossal nucleus in the posterior paramedian medulla beneath the hypoglossal eminence of the floor of the fourth ventricle. The hypoglossal nucleus extends nearly the entire craniocaudal extent of the medulla (Figs. 12.1, 12.2). Hypoglossal rootlets travel ventrolaterally within the medullary reticular formation, lateral to the medial longitudinal fasciculus and medial lemniscus, and emerge from the medulla at the preolivary (anterior lateral) sulcus between the inferior olive and the pyramid. In the premedullary cistern, the 10 to 15 small hypoglossal rootlets lie in close proximity to the intracranial vertebral artery, converge into two nerve bundles, and penetrate the dura to enter the bony hypoglossal canal (Fig. 12.3) inferior and medial to the jugular foramen.

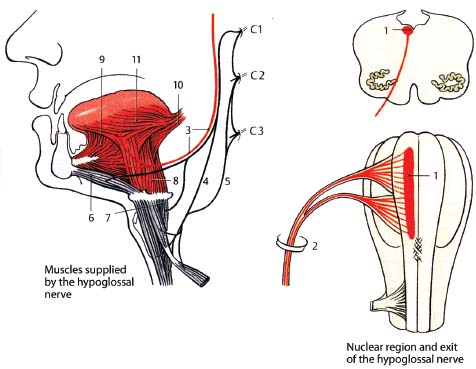

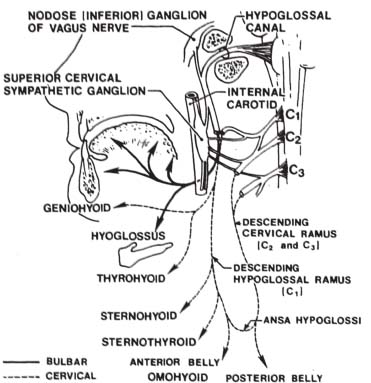

• After passing through the hypoglossal canal, the hypoglossal nerve turns sharply inferiorly. It then enters and runs for several centimeters in the carotid sheath medial to CNs IX/X/XI, which have exited the jugular foramen and entered the carotid space. The hypoglossal nerve descends between the internal carotid artery (ICA) and the internal jugular vein (IJV) in the nasopharyngeal carotid space to the level of the transverse process of the atlas, where it turns forward along the lateral surface of the ICA and the external carotid artery (ECA) , entering the digastric triangle of the neck above the level of the hyoid bone and deep to the posterior belly of the digastric muscle. Here it ramifies into muscular branches that supply most of the extrinsic muscles of the tongue (styloglossus, hyoglossus, and genioglossus) before supplying all of the intrinsic muscles of the tongue (longitudinal, transverse, and vertical muscles) (Fig. 12.4).

• In its course, the hypoglossal nerve travels with fibers from the nodose ganglion of the vagus nerve, postganglionic sympathetic fibers from the superior cervical ganglion, and fibers from C1 (Fig. 12.4). As CN XII crosses the ICA, most of the fibers from C1 separate from CN XII and course inferiorly as the descending hypoglossal ramus (descendens hypoglossi) (superior root of the ansa hypoglossi); this unites with the descending cervical ramus (inferior root of the ansa hypoglossi), which consists of fibers from C2 and C3 (Fig. 12.4). The ansa hypoglossi provides motor innervation to three infrahyoid strap muscles (sternohyoid, sternothyroid, and omohyoid). The other strap muscle (thyrohyoid) and the geniohyoid muscle are innervated by C1 fibers that initially travel with the main trunk of CN XII and are not part of the ansa (Fig. 12.4).

• Summary of submandibular region/strap muscle innervation (Table 12.1).

• Supranuclear control of CN XII is via corticobulbar fibers from the lower precentral gyrus. There is bilateral supranuclear innervation of all CN XII-innervated muscles except for the genioglossus, which is crossed and unilateral.

Fig. 12.1 Cross-sectional diagram of the lower medulla. The hypoglossal nucleus lies in the floor of the fourth ventricle. The slight bulge into the fourth ventricle is termed the hypoglossal eminence. Hypoglossal rootlets project ventrally through the medulla to emerge in the preolivary sulcus. Note the proximity of the cisternal portion of the hypoglossal nerve to the vertebral artery. (From Smoker WRK. The hypoglossal nerve. Neuroimaging Clin North Am 1993;3:193–206. Reprinted with permission.)

Fig. 12.2 Hypoglossal nerve. (1, nucleus of the hypoglossal nerve; 2, hypoglossal canal; 3, hypoglossal nerve; 4, descending hypoglossal ramus of cervical plexus; 5, descending cervical ramus of cervical plexus; 6, geniohyoid muscle; 7, thyrohyoid muscle; 8, hyoglossus; 9, genioglossus; 10, styloglossus; 11, intrinsic muscles of the tongue.)

Fig. 12.3 Nuclear origins and cisternal courses of glossopharyngeal, vagus, and spinal accessory nerves. Note that the glossopharyngeal nerve traverses the more anterior part of the jugular foramen (pars nervosa), whereas the vagus and spinal accessory nerves pass through the posterior part (pars vascularis). The hypoglossal nerve is shown exiting through the more inferiorly located hypoglossal canal. (1, nucleus solitarius; 2, dorsal motor nucleus of CN X; 3, nucleus ambiguus; 4, superior salivatory nucleus; C XI, cranial root of CN XI; S XI, spinal root of CN XI.) (From Harnsberger HR. Handbook of Head and Neck Imaging (2nd ed.) St. Louis, MO: Mosby, 1995. Reprinted with permission.)

Fig. 12.4 Peripheral connections of the hypoglossal nerve. Note the communication of the hypoglossal nerve with fibers from C1, the nodose ganglion of the vagus nerve, and the superior cervical (sympathetic) ganglion. Structures supplied by the hypoglossal nerve are indicated by solid lines, whereas those supplied by fibers of cervical origin are indicated by dashed lines. The hypoglossal nerve provides motor innervation to the extrinsic (hyoglossus, styloglossus, and genioglossus) and intrinsic muscles of the tongue. Note the ansa hypoglossi, formed by the descending hypoglossal and cervical rami. See text for details. (From Smoker WRK. The hypoglossal nerve. Neuroimaging Clin North Am 1993;3:193-206. Reprinted with permission.)

| Muscle | Innervation | |

|---|---|---|

| Mylohyoid | V3 | |

| Digastric, anterior belly | V3 | |

| Digastric, posterior belly | VII | |

| Stylohyoid | VII | |

| Palatoglossus | X (via pharyngeal plexus) | |

| Styloglossus | XII | |

| Hyoglossus | XII | |

| Genioglossus | XII | |

| Intrinsic tongue muscles | XII | |

| Geniohyoid | C1 (not via ansa hypoglossi) | |

| Thyrohyoid | C1 (not via ansa hypoglossi) | |

| Sternohyoid | Ansa hypoglossi (C1–C3) | |

| Sternothyroid | Ansa hypoglossi (C1–C3) | |

| Omohyoid | Ansa hypoglossi (C1–C3) |

Hypoglossal Nerve: Normal Images (Figs. 12.5, 12.6, 12.7, 12.8, 12.9)

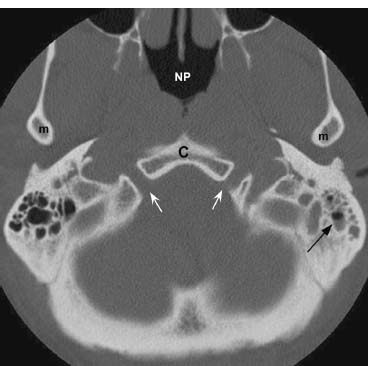

Fig. 12.5 Axial CT image in bone window at the level of the hypoglossal canals (white arrows). Also shown are clivus (C), nasopharyngeal airway (NP), and inferior aspect of the mandibular condyles (m). A small amount of fluid is incidentally noted in the left mastoid air cells (black arrow).

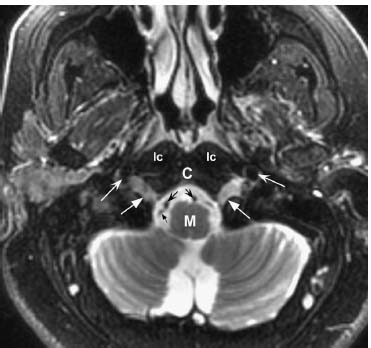

Fig. 12.6 Axial fast spin echo T2-weighted image with fat saturation at a similar level as in Fig. 12.5. Normal somewhat high signal is noted within the hypoglossal canals bilaterally (straight white arrows). Normal flow voids adjacent to the medulla (M) represent the vertebral arteries (concave black arrows). A smaller flow void (straight black arrow) posterolateral to the right vertebral artery represents the posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA) arising from the adjacent vertebral artery. Anterolateral to the hypoglossal canal are flow voids within the internal carotid arteries (concave white arrows). (C, clivus; lc, longus colli muscles.)

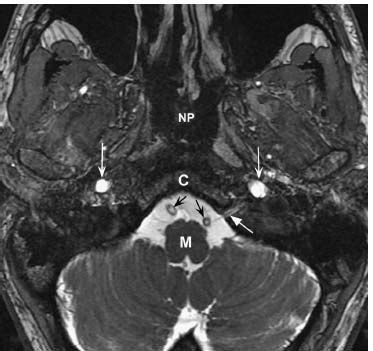

Fig. 12.7 An axial high-resolution fast imaging employing steadystate acquisition (FIESTA) image at the level of the medulla (M) demonstrates the left hypoglossal nerve as it enters the hypoglossal canal (straight white arrow). Normal vertebral arteries (black arrows) are present within the premedullary cistern. Normal T2 hyperintensity is seen within the internal carotid arteries bilaterally (concave white arrows). (C, clivus; NP, nasopharynx.)

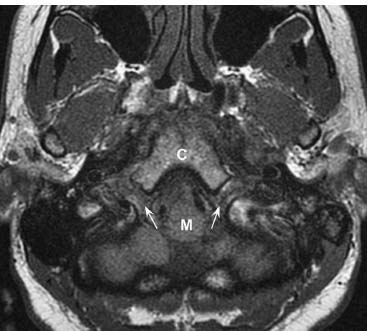

Fig. 12.8 Axial T1-weighted image at the level of the medulla (M) demonstrates normal intermediate signal within the hypoglossal canals (arrows). (C, clivus.)

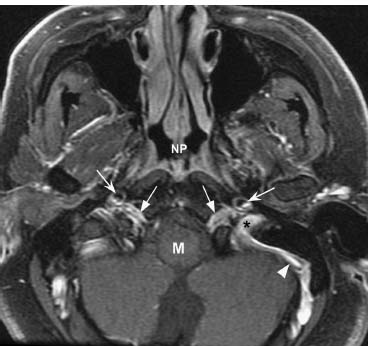

Fig. 12.9 An axial post-gadolinium T1-weighted image with fat saturation at a similar level shows normal symmetric enhancement within the hypoglossal canals (straight arrows), predominantly due to enhancement of normal venous structures such as the anterior condylar veins. Normal enhancement is noted within the left sigmoid sinus (arrowhead) extending into the internal jugular vein. The left jugular foramen (*) is shown, located posterior and lateral to the hypoglossal canal. The internal carotid arteries are seen as flow voids (concave arrows) anterolateral to the hypoglossal canals. (M, medulla; NP, nasopharynx.)

Hypoglossal Nerve Lesions

Evaluation

• Observation of the tongue at rest and with protrusion and movement is necessary. Examination of tongue movement to the left and right against resistance may also be performed.

• The key to understanding which way the tongue will deviate with lesions is to understand the normal action of the genioglossus muscle, which is to draw the root of the tongue forward and cause it to protrude. Therefore, a unilaterally weak genioglossus muscle will lead to imbalance and deviation of the tongue toward the weak side on protrusion.

• Supranuclear upper motor neuron (UMN) pathology affecting hypoglossal function results in paresis of the contralateral genioglossus muscle, with resulting deviation of the tongue away from the side of the lesion (toward the side of the paretic genioglossus muscle).

• Nuclear (brainstem) and unilateral lower motor nerve (LMN) lesions result in ipsilateral hemitongue paresis, atrophy, fibrillations, and fasciculations. There is deviation of the tongue toward the side of the lesion (again, toward the side of the paretic genioglossus muscle).

• Dysarthria is impaired speech due to abnormal neuromuscular control, manifest as abnormalities of articulation, prosody, resonance, and phonation. Particular difficulty with lingual consonants (D, T, L) is seen with hypoglossal pathology.

• Unilateral hypoglossal palsy leads to paresis, atrophy, fibrillations, and fasciculations in the affected half of the tongue and mild dysarthria. Bilateral lesions result in bilateral tongue atrophy, weakness, and fibrillations, and severe dysarthria and dysphagia. Oropharyngeal airway compromise may occur due to tongue flaccidity.

Types

Supranuclear Lesions

• Occur from the level of the precentral gyrus to the hypoglossal nucleus (e.g., ischemic infarction).

• UMN hypoglossal deficit (described above) is typically associated with other neurologic findings (most commonly hemiparesis/hemiplegia).

• Not usually associated with atrophy/fasciculations/fibrillations.

• Spastic dysarthria may result from poor supranuclear control of the tongue.

• Bilateral supranuclear lesions (e.g., pseudobulbar palsy from repeated infarctions) may lead to bilateral tongue paralysis and severe dysarthria.

Nuclear Lesions

• Rare to cause CN XII palsy in isolation.

• Unilateral lesions result in a unilateral LMN syndrome (described above).

• Causes of nuclear injury include the following:

Vascular. Medial medullary syndrome (Dejerine anterior bulbar syndrome), due to occlusion of vertebral or anterior spinal artery. This involves the ipsilateral pyramid, medial lemniscus, and hypoglossal nucleus, and results in ipsilateral LMN palsy of CN XII as well as contralateral hemiplegia and loss of position/vibratory sensation (with facial sparing). See Appendix A.

Vascular. Medial medullary syndrome (Dejerine anterior bulbar syndrome), due to occlusion of vertebral or anterior spinal artery. This involves the ipsilateral pyramid, medial lemniscus, and hypoglossal nucleus, and results in ipsilateral LMN palsy of CN XII as well as contralateral hemiplegia and loss of position/vibratory sensation (with facial sparing). See Appendix A.

Infectious/inflammatory (e.g., infectious mononucleosis, bulbar poliomyelitis).

Infectious/inflammatory (e.g., infectious mononucleosis, bulbar poliomyelitis).

Neoplasm (e.g., brainstem glioma).

Neoplasm (e.g., brainstem glioma).

Demyelinating disease (e.g., multiple sclerosis [MS]).

Demyelinating disease (e.g., multiple sclerosis [MS]).

Neurodegenerative disease (e.g., progressive bulbar palsy).

Neurodegenerative disease (e.g., progressive bulbar palsy).

Syringobulbia.

Syringobulbia.

Premedullary Subarachnoid Space and Hypoglossal Canal Lesions

• Result in unilateral LMN syndrome.

• Often involve adjacent CNs (IX, X, XI) (e.g., Collet-Sicard syndrome: IX–XII palsies).

• Causes of injury include the following:

Neoplasms (e.g., hypoglossal schwannoma, meningioma, skull base metastasis, extension of jugular foramen lesions such as paraganglioma. Also, nasopharyngeal carcinoma and other head and neck malignancies may extend posteriorly to the lower clivus and hypoglossal canal.).

Neoplasms (e.g., hypoglossal schwannoma, meningioma, skull base metastasis, extension of jugular foramen lesions such as paraganglioma. Also, nasopharyngeal carcinoma and other head and neck malignancies may extend posteriorly to the lower clivus and hypoglossal canal.).

Trauma (e.g., occipital condyle fracture or basal skull fracture through the hypoglossal canal).

Trauma (e.g., occipital condyle fracture or basal skull fracture through the hypoglossal canal).

Infection (e.g., skull base osteomyelitis may affect CN XII, often in association with other CN palsies).

Infection (e.g., skull base osteomyelitis may affect CN XII, often in association with other CN palsies).

Vascular (e.g., vertebral dissection or dolichoectasia).

Vascular (e.g., vertebral dissection or dolichoectasia).

Extracranial Lesions

• Proximal extracranial lesions may involve vessels (ICA and IJV) and other lower CNs (IX, X, XI) as they travel together in the upper carotid space.

• Lesions within the carotid space:

Vascular (e.g., ICA aneurysm or dissection)

Vascular (e.g., ICA aneurysm or dissection)

Infectious/inflammatory (e.g., neck abscess, tuberculosis, rheumatoid arthritis)

Infectious/inflammatory (e.g., neck abscess, tuberculosis, rheumatoid arthritis)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree