HYPOPHARYNX: MALIGNANT TUMORS

KEY POINTS

- Computed tomograhy and magnetic resonance imaging are important tools for establishing the extent of the primary tumor, especially in the postcricoid and esophageal verge areas.

- Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging are important tools for establishing the extent of cervical and retropharyngeal lymph node metastases.

- These factors help to determine optimal treatment strategies.

- Used judiciously, fluorine-18 2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) can further aid this diagnostic process.

- Surveillance imaging can be by a combination of anatomic and/or radionuclide imaging.

The basic staging and medical decision-making procedures for hypopharyngeal cancer include indirect laryngoscopy, direct laryngoscopy with biopsy, contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) or contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance (CEMR) depending on the practice preference, and a chest x-ray. The imaging studies are essential in this clinical-diagnostic evaluation, providing unique and often pivotal information. Imaging provides additional information concerning the deep extent and regional spread of disease. Chest computed tomography (CT) and FDG-PET are necessary in selected cases.

This chapter describes the important role of diagnostic imaging in clinical decision making for hypopharyngeal cancer. Squamous cell carcinoma (SCCA) will be discussed in the first section and the less common malignant tumors in the second section.

ANATOMIC CONSIDERATIONS

Applied Anatomy

A thorough knowledge of the following anatomy and anatomic variations of normal in each of the these areas is required for the evaluation of hypopharyngeal malignant tumors. This anatomy is presented in detail with the introductory material on the larynx, hypopharynx, cervical esophagus, and infrahyoid neck in general:

Primary Site Evaluation

- With regard to the hypopharynx and esophagus, knowledge of the detailed relationship of the hypopharynx to the larynx and pyriform sinus apex region is required. The relationship of the postcricoid region and esophageal verge must be completely understood. As well, the relationship of the postcricoid region and the upper cervical esophagus to the upper trachea and thyroid gland is important adjunctive information (Chapters 201, 209, and 221).

- With regard to the larynx, the relationship of mucosal landmarks and functional structures of the larynx to the hypopharynx is critical knowledge for assessing tumor spread in this region. This fund of knowledge must include the detailed anatomy of the laryngeal skeleton and its normal variations as well as the paraglottic space (PGS) and pre-epiglottic space (PES) relationships to the hypopharynx (Chapters 149, 201, and 221).

- Tongue base region and low oropharyngeal wall (Chapter 190).

Evaluation of Extrapharyngeal Spread

- Visceral compartment of the neck, thyroid gland, trachea, and related fasciae (Chapter 149).

Evaluation of Regional Lymph Node Disease

- Detailed knowledge of normal node and perinodal morphology and the common drainage pathways of laryngeal cancer, which emphasizes nodal levels 2 through 6 (Chapters 149 and 159).

Evaluation of Perivascular and Perineural Spread

- Knowledge of the entire course of the vagus and recurrent laryngeal nerves on both sides and of the superior laryngeal neurovascular bundle (Chapter 201).

IMAGING APPROACH

Techniques and Relevant Aspects

The hypopharynx is studied in essentially the same manner as the larynx for the evaluation of known cancer and masses of uncertain etiology. The principles of using these studies are reviewed in Chapters 201, 206, and 215. Specific problem-driven protocols for CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the hypopharynx and larynx are presented in Appendixes A and B.

There is little or no use for ultrasound in studying hypopharyngeal cancer or masses of uncertain etiology. It is used in some practices to assess the risk of lymph node metastases.

The approach with radionuclide studies depends on the aim of the examination. Most of the current usage is limited to cancer evaluation with FDG-PET. This is discussed in more detail in conjunction with the larynx (Chapter 201).

Pros and Cons

Indications for Study in Potential Hypopharyngeal Cancers

Evaluation of the Primary Site and Regional Disease

Almost all hypopharyngeal carcinomas are studied with imaging. CT is usually the initial examination. The primary tumor and all cervical and retropharyngeal nodes must be studied. MRI is used most efficiently in a supplemental role as directed by CT findings to localized areas of interest, usually the lower extent of the tumor at the pyriform sinus apex, postcricoid region, and esophageal verge (Figs. 219.1–219.4).

All primary tumors must be evaluated for the extent of the hypopharyngeal spread of the primary; cartilage invasion; spread to adjacent structures including the larynx, oropharyngeal walls, trachea, and esophagus; and extrapharyngeal spread to the soft tissues of the neck (Figs. 219.1–219.4). The evaluation must also include a search for regional adenopathy (Fig. 219.5) and spread along neurovascular bundles at risk (Figs. 219.3 and 219.4). Finally, the risk of any acute adverse complication, such as rapidly progressive airway obstruction, should be anticipated.

There are several areas where CT or magnetic resonance (MR) images consistently provide better information than the endoscopic examination. These include sometimes entirely submucosal spread to the postcricoid region upper cervical esophagus (Figs. 219.6 and 219.7) and larynx including the PGS and PES, laryngeal cartilage invasion (Figs. 219.6 and 219.7), and spread to the extrapharyngeal soft tissue of the neck along several pathways including the superior laryngeal neurovascular bundle (Figs. 219.6–219.8). These imaging studies also allow tumor volumes that may reside in these deep spaces to be measured along with the more exophytic component (Fig. 219.8F–H).

MRI strengths related to soft tissue contrast resolution may be exploited to help in making critical management decisions. In the hypopharynx, MR is most often used to study lesions that on CT are suspicious for submucosal spread within the postcricoid region that threaten spread toward or involve the esophageal verge (Figs. 219.7 and 219.9). This information is critical to surgical planning. A significant proportion of MR studies used to more generally evaluate hypopharyngeal cancer will be of poor quality owing to motion artifacts.

Detection of Recurrent Tumor

Diagnostic CT is the examination for detection of recurrence in the neck, study of the neopharynx, or the irradiated larynx and hypopharynx; in selected cases, FDG-PET may be useful. These issues are detailed more completely in the section on posttreatment surveillance that follows later in this chapter.

Evaluation of Hypopharyngeal and Laryngeal Dysfunction and Submucosal Masses

Some patients have SCCAs growing entirely beneath intact mucosa. The can cause vocal cord or swallowing dysfunction. Rarely, these tumors may arise out of sight of the endoscopist in the pyriform sinus apex or postcricoid region (Fig. 219.6) and grow anteriorly into the PGS. Submucosal masses are rarely caused by other submucosal tumors, such as minor salivary and benign mesenchymal tumors, and cannot be distinguished from squamous cell cancers. These may actually present first as a palpable neck mass. A rare paraganglioma might be anticipated when a mass bulging from the medial pyriform sinus wall shows intense vascularity and an enlarged superior laryngeal vascular bundle (Fig. 218.5). About half of all submucosal laryngeal masses will be a laryngocele (Chapter 203) that can mimic a submucosal mass arising along the lateral and or medial wall of the pyriform sinus. The presence of a laryngocele always requires a search for an obstructing primary tumor (Figs. 203.3 and 203.6). Deformity of the laryngeal skeleton due to old trauma or developmental variations may cause hypopharyngeal dysfunction and a mucosal bulge in the parapharyngeal space and pyriform sinus region that is readily recognized on CT or MR images. These conditions are discussed in more detail elsewhere (Chapters 150, 203, 205, and 207).

FIGURE 219.1. Diagram of spread patterns of pyriform sinus cancer.

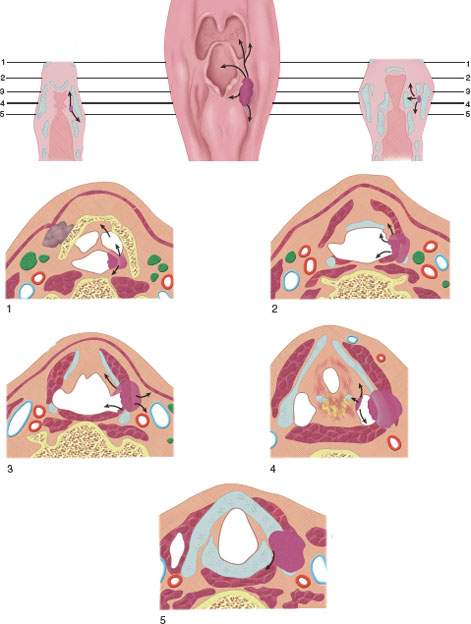

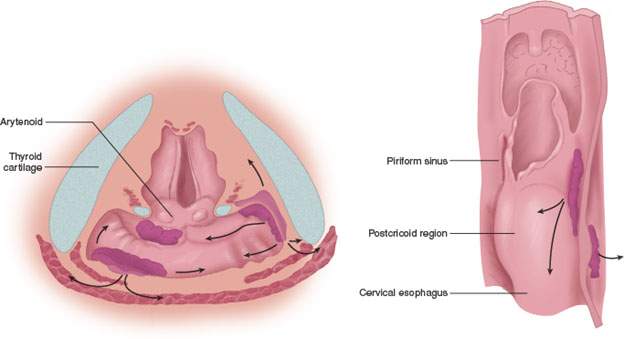

FIGURE 219.2. Diagrams depicting spread patterns of posterior pharyngeal wall and postcricoid cancers, including those that secondarily involve the postcricoid region from the pyriform sinus apex. An important pathway is the potential for tumor spread within and through the muscular wall of the postcricoid region or entirely outside its muscular wall in addition to mucosal spread. The latter can be assessed endoscopically, while the deeper spread patterns must be studied by detailed imaging through the postcricoid and esophageal verge region.

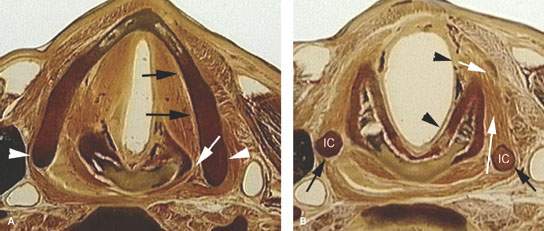

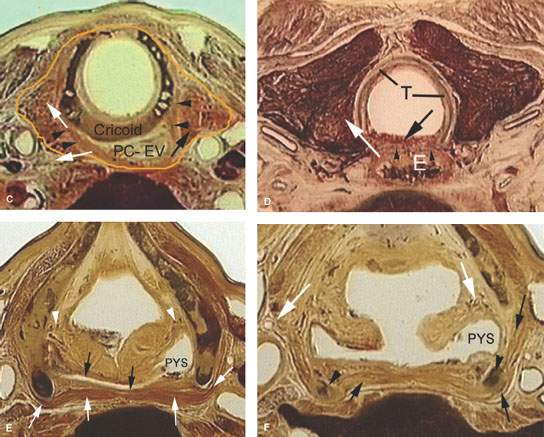

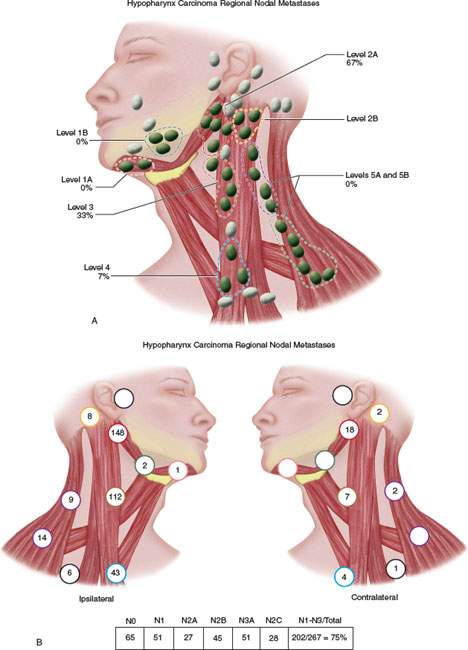

FIGURE 219.3. Anatomic whole organ sections in the axial plane to demonstrate the anatomic basis for some of the spread patterns seen with hypopharyngeal cancer. A: At the true vocal cord level, the pyriform sinus apex lies just lateral to the cricoarytenoid joint (white arrow). Note that the inferior constrictor muscle attaches to the thyroid lamina (arrowheads). This provides a point of possible point cartilage invasion by cancer spreading along the muscular pharyngeal wall; this is a frequent site of invasion. Also, the anterior continuity with the paraglottic space (PGS) (black arrows) shows how tumor can spread in that direction beneath intact mucosa. B: A section taken through the mid postcricoid region showing the attachment of the postcricoid muscular wall (black arrows) to the inferior cornua of the thyroid cartilage (IC). These attachments show how tumor spreading within and through the muscular wall may do so both along the mucosal surface (black arrowheads) and into the deep spaces outside the pharynx (white arrows). Either or both spread patterns may occur. Much of such spread is out of view of the endoscopist. C: At the region of the lower postcricoid hypopharynx and esophageal verge (PC-EV), the pharynx begins to lose its attachment to the laryngeal skeleton. Tumor may spread within those muscular attachments (arrowheads) or outside the muscular wall (white arrows) at this point. This may lead to invasion of the thyroid gland (black arrow). D: At the level of the first tracheal ring (T), the esophagus (E) is now visible, and submucosal spread from the esophageal verge into the esophagus may occur and not be visible endoscopically. Such spread may invade the common membranous wall between the trachea and esophagus (black arrow) or invade the thyroid gland (white arrow). E: A section through the lower supraglottic region showing the relation of the pyriform sinus (PYS) and the membranous wall of the larynx on one side and the thyroid cartilage on the other. The superior laryngeal neurovascular bundle (arrowheads) eventually pierces the thyrohyoid membrane, but at this level is ramifying in the PGS and aryepiglottic fold. Note that the inferior constrictor muscle attaches to the thyroid lamina (white arrows). This provides a point of possible cartilage invasion by cancer spreading along the muscular pharyngeal wall; this is a frequent site of invasion. The white arrows show the mucosa of the arytenoid pad and posterior pharyngeal wall as separate layers, explaining the nuances of imaging patterns seen in cancers that involve these structures. F: At the mid supraglottis, the superior laryngeal neurovascular bundle penetrates the membranous laryngeal wall (white arrow). The muscular pharyngeal wall (black arrows) attaches to the superior cornu of the thyroid lamina and continues around to the muscle’s laminar attachment. These points of attachment are areas where cartilage invasion often begins.

FIGURE 219.4. Coronal whole organ sections to show spread patterns of hypopharyngeal cancer. A: A section showing the upper pyriform sinus apex (arrowheads) relationship to the thyroid cartilage and potential spread patterns from the apex between the thyroid and cricoid (C) cartilages. The attachment of the constrictor muscles laterally shows how these might direct tumor between the laryngeal skeleton and the upper trachea (white arrows). Continuity between the subglottis, the region of the esophageal verge (arrows), and the tracheal wall, as well as mucosal continuity in this region, is shown by the black arrow; the tracheal cartilages are shown by the black arrowheads. B: A section showing the superior laryngeal neurovascular bundle within the larynx (black arrows) as it extends through the thyrohyoid membrane to the neck below the hyoid bone (H). This is an area of weakness that allows tumors to grow outside the larynx. The black arrowhead shows the constrictor muscle of the pharynx as it attaches to the thyroid cartilage (T). On the left side, white arrows show the superior laryngeal nerve within the paraglottic space, which is the part of the neurovascular bundle that allows cancers to grow out of the larynx that are undetectable except by imaging. C: The most posterior section of these three sections showing the relationship of the pharyngeal constrictor muscles (black arrows) to the cricoid cartilage (C) and inferior cornu of the thyroid cartilage (IC). From this, it can be seen how cancers growing in the postcricoid region can gain access to the cervical esophagus (black arrowheads) by growing within or on either side of the pharyngeal muscles and how tumor outside the musculature invades the deep soft tissues of the neck and the thyroid gland (T).

Controversies

Cartilage Invasion

CT and MR vastly improve the clinical detection of subtle cartilage invasion. A thin (,3 mm) slice thickness is preferred for this task so that CT is likely the better choice as the primary examination. Some reports suggest that MR is better than CT for detection of early cartilage invasion. CT and MR are both imperfect in detecting early macroinvasion and, of course by definition, cannot directly show micro invasion. This issue is discussed in detail with regard to laryngeal cancer (Chapter 206).

FDG-PET for Staging and Other Indications

In most hypopharyngeal neoplasms, FDG-PET has a limited primary role, as this technique does not allow one to reliably assess the anatomic extent of the lesion and the possible invasion of the tumor into adjacent structures. Its value in determining or planning a more accurate gross target volume (GTV) for radiotherapy (RT), planning in hypopharyngeal cancer remains unproven with regard to it providing some incremental survival benefit (Chapter 5).

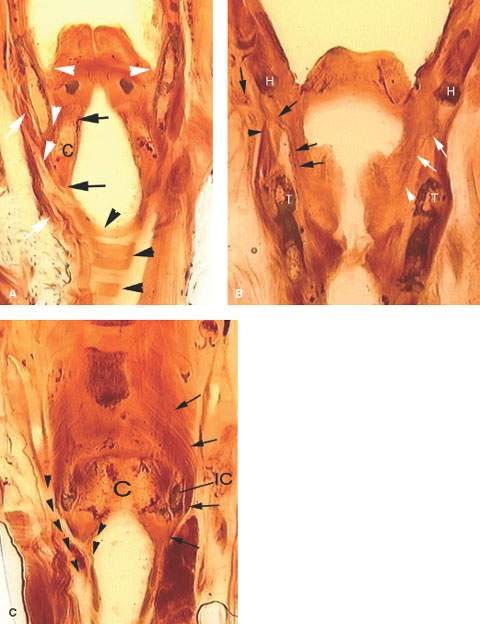

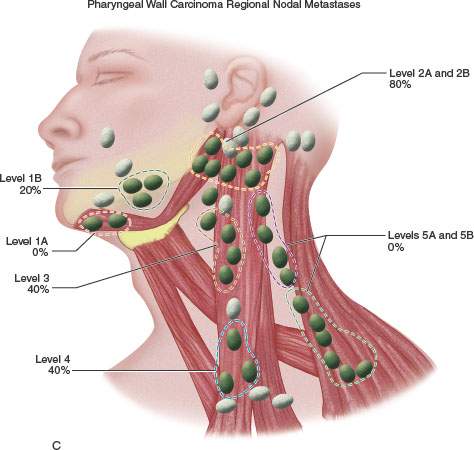

FIGURE 219.5. A–C: Diagrams showing patterns of adenopathy in hypopharyngeal and posterior pharyngeal wall cancers.

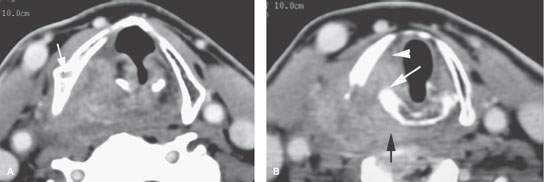

FIGURE 219.6. A patient with an over 1-year history of hoarseness. The patient had multiple endoscopic examinations that showed no tumor. Computed tomography was finally done. A: At the level of the false cord, an infiltrating tumor of the pyriform sinus is present, and there is sclerosis and loss of the marrow space within the right thyroid lamina. B: At the apex of the pyriform sinus, the tumor grows into the postcricoid hypopharynx (black arrow), disrupts the cricoarytenoid joint (white arrow), and grows into the paraglottic space, explaining the patient’s true vocal cord dysfunction. All of the cancer was submucosal. C: Continued growth outside the larynx invading the upper pole of the thyroid gland (arrowheads) and extending well into the postcricoid region. The cricoid is sclerotic, which is consistent with likely invasion. D: Continued postcricoid spread is present on the right, probably both within and outside the muscular wall of the pharynx (arrow), compared to the normal side (arrowhead). E: At the level of the first tracheal ring and upper cervical esophagus, the tumor is still invading the muscular wall of the esophagus and displacing the right thyroid lobe compared to normal side (arrowhead). F: Bone windows to correlate with cartilage changes seen earlier. There is obvious erosion of the thyroid cartilage at the point of attachment of the pharyngeal constrictor muscle (arrow) and chronic erosion along the posterior margin of the cricoid cartilage (arrowhead), which is consistent with the long history. G: The cricoid cartilage is sclerotic—a finding associated with a relatively high risk of invasion.

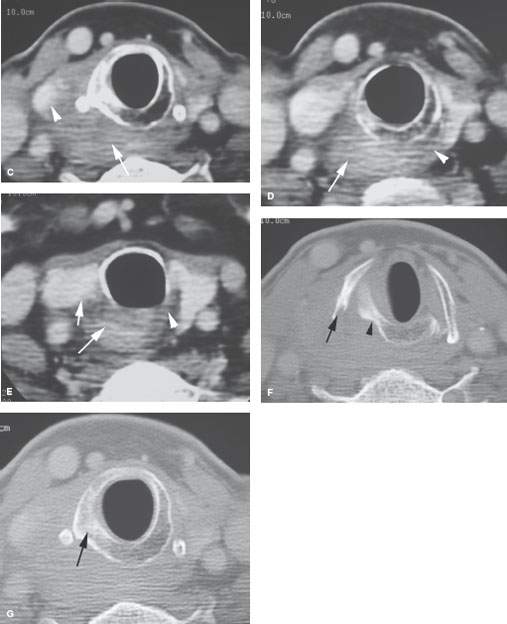

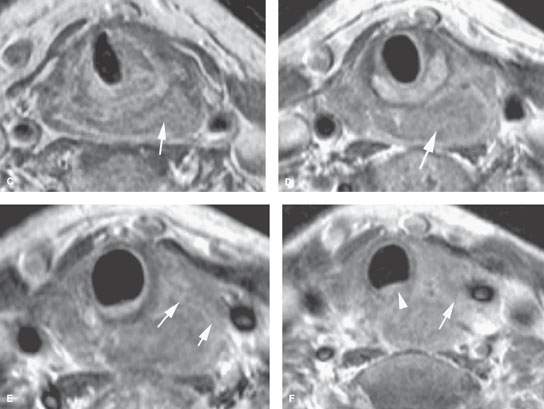

FIGURE 219.7. A patient with squamous cell cancer of the right pyriform sinus. A: On the T2-weighted axial image, the cancer invades the paraglottic space (arrow) and also invades the pharyngeal constrictor muscle (white arrowhead). The tumor extends along the constrictor muscle to the posterolateral margin of the thyroid cartilage (curved arrow). Metastatic lymph nodes are shown in level 3 (black arrowheads). B, C: Plain and gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted axial images at the same level as (A). The primary tumor shows some central necrosis. The lymph nodes in level 3 enhance abnormally due to metastatic disease. D, E: Gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted axial images at the level of the pyriform sinus apex (D) and mid postcricoid region arch (E). The tumor grows into the paraglottic space at the true cord level (arrowheads in D). In (E), the tumor has spread well below the pyriform sinus apex (arrow) to invade the thyroid cartilage inferior cornu as it begins to spread between the cricoid and thyroid cartilages (arrowheads).

FDG-PET can detect neck nodal metastasis with a relatively high accuracy, but both false-positive and false-negative results occur. Although FDG-PET sometimes detects nodal metastasis missed by other imaging techniques, the high cost of this technique does not warrant its routine use for this indication since the nodes on both sides must be included in all treatment plans. Anatomic imaging will aid the initial treatment planning strategy more than FDG-PET data in patients with advanced neck disease.

In patients with advanced hypopharyngeal cancer, FDG-PET is useful to detect distant metastases and to exclude coincident primary tumors outside the head and neck region.

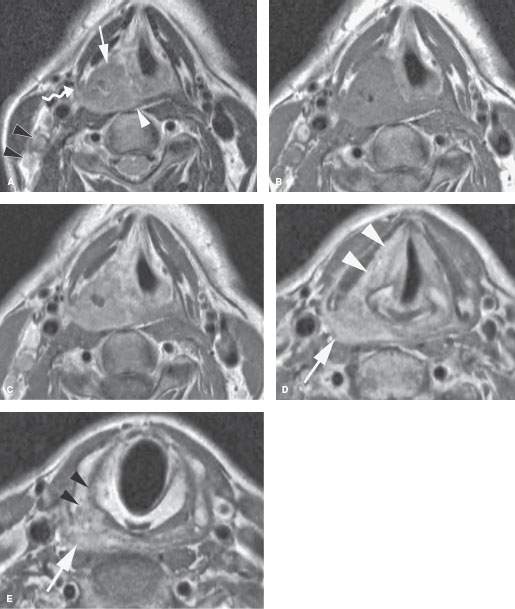

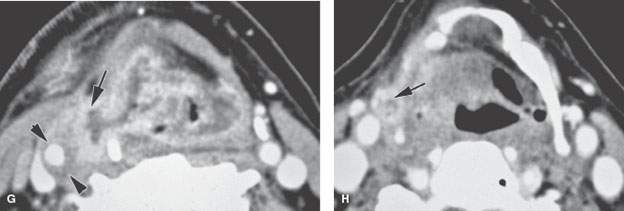

FIGURE 219.8. Three patients demonstrating extralaryngeal spread. Computed tomography studies were done in all patients. The spread outside the pharynx was not detectable in any of the patients on the basis of the clinical examination. A–C: Patient 1. A low-volume but locally aggressive-appearing pyriform sinus carcinoma invading the right superior laryngeal neurovascular bundle (arrows in A) and spreading outside the larynx. In (B), that spread pattern along the superior neurovascular bundle can be seen again (arrows) with an associated metastatic lymph node. In (C), submucosal spread to the junction of the hypopharyngeal and oropharyngeal posterior walls is present (arrow), and there is a positive level 2 lymph node containing multiple peripheral metastatic deposits (arrowheads). D, E: Patient 2. There is an almost entirely exophytic pyriform sinus and aryepiglottic fold cancer (arrow). However, the tumor can be seen spreading along the superior laryngeal neurovascular bundle outside the larynx (arrowhead). There is an associated level 3 metastatic lymph node that is completely replaced by tumor (white arrow). In (E), the tumor, which on its surface appears relatively lobulated and exophytic, shows evidence of probable early thyroid lamina invasion (arrow). F–H: Patient 3. A very aggressive cancer can be seen growing through the thyrohyoid membrane along the superior laryngeal neurovascular bundle (arrows in F and G). The carotid artery is encased by this tumor growth, as seen in (G). Spread along the superior laryngeal neurovascular bundle is sometimes associated with or due to lymph nodes (arrow) along this bundle, as demonstrated in (H).

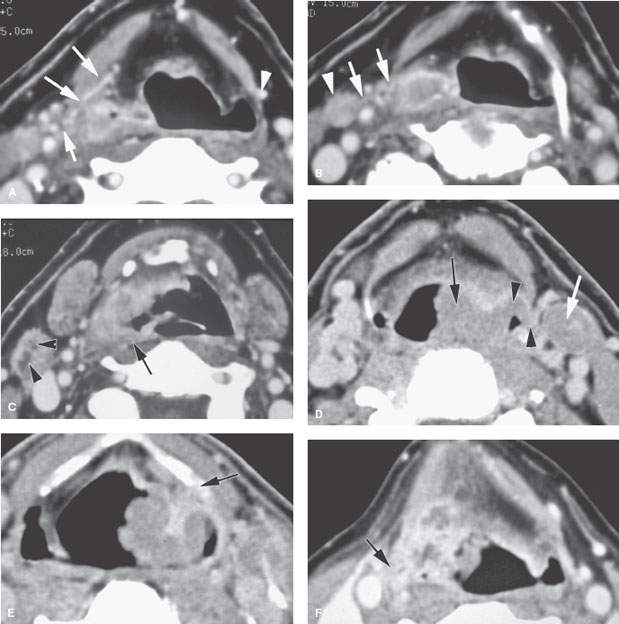

FIGURE 219.9. Two patients showing posterior pharyngeal wall and postcricoid cancers. A: Patient 1. Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted sagittal image in a patient with posterior hypopharyngeal wall cancer (between black arrows). The lesion extends in the postcricoid hypopharynx and reaches the lower margin of the cricoid cartilage (white arrowhead), corresponding to the level of the esophageal inlet or verge. The proximal esophagus (curved arrow) has a normal appearance. Arytenoid cartilage is shown as well (arrowhead). B–F: Patient 2 has a mainly postcricoid carcinoma. A magnetic resonance imaging study was done to determine the lower extent of the lesion relative to the cervical esophagus for planning of pharyngeal and possibly esophageal reconstruction. In (B), a non–contrast-enhanced T1-weighted image shows the lesion to be most bulky in the postcricoid region but to extend grossly from the lower posterior hypopharyngeal wall to the inlet of the cervical esophagus. In (C) through (F), the full extent of the lesion is shown more precisely. In (C), the tumor is seen below the apex of the pyriform sinus in the postcricoid region infiltrating both the anterior and posterior muscular walls of the hypopharynx on the left (arrow) and extending across the midline. In (D), the tumor fills the postcricoid hypopharynx just above the region of the esophageal verge (arrow). In (E), there is gross tumor at the esophageal verge that infiltrates the left thyroid lobe (arrows). In (F), the cancer is shown to be involving the upper cervical esophagus, invading the common wall between the trachea and esophagus; this is clear evidence of tracheal involvement (arrowhead). The left thyroid lobe is invaded (arrow). The lower limit of this tumor was well into the cervical esophagus. The patient was reconstructed using a gastric pull-up.

This technique must be used with discernment rather than applied indiscriminately for diagnosis and staging given its expense and often low potential to truly alter management decisions or have a measurable survival benefit.

Some investigators suggest that high fluorine-18 2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) uptake may be a useful parameter for identifying aggressive tumors. Patients with a high standard uptake value (SUV) appear to be more resistant to the effects of RT with or without chemotherapy.1 A high SUV is also a negative predictive factor in patients primarily treated by surgery and postoperative RT.2 Currently, there is no agreement on how this information should be used in planning patient management. Also, specific SUV levels must be established at each institution. While trends related to SUV may apply across institutions, specific values related to trends are not necessarily transportable from one FDG-PET facility to another.

SPECIFIC DISEASE/CONDITION

Hypopharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Etiology

Cancer of the hypopharynx is clearly linked to cigarette smoking and postcricoid cancer associated with the Plummer-Vinson syndrome; this is rarely seen in the United States and continental Europe but is more commonly encountered in the United Kingdom.3

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Hypopharyngeal cancer is about four times less common than laryngeal cancer. Hypopharyngeal cancer is mostly seen in the age group between 50 and 70 years. About 71% arises in the pyriform sinus, 17% in the postcricoid region, and 12% on the posterior hypopharyngeal wall.4 This cancer is more prevalent in men than in women; only postcricoid cancer is more common in women because of the association with Plummer-Vinson syndrome, which occurs almost exclusively in women.5

Clinical Presentation

Pharyngeal wall and pyriform sinus cancers usually present with sore throat. Unilateral sore throat is a particularly worrisome symptom since sore throat from pharyngitis is almost always bilateral. Dysphagia, sensation of foreign body in the throat, otalgia, bloody saliva, aspiration, and voice change are typically later findings associated with more advanced disease.

Hoarseness is usually not an early presenting symptom in patients with hypopharyngeal cancer. Changes in voice quality do occur. Dysphagia and referred otalgia (from the vagus to Arnold nerve) are common presenting complaints. In hypopharyngeal cancer, a neck mass due to metastatic adenopathy is a common presenting sign.

Physical examination is mainly done by rigid and flexible fiber-optic endoscopes. The physical examination should establish whether the vocal cord is mobile, paretic, or fixed. The exact relationship of tumor to the pyriform sinus, postcricoid region, and esophageal verge may be uncertain even after careful direct endoscopy.

Localized pain or tenderness to palpation over the thyroid lamina suggests gross invasion of the cartilage.

A palpable neck mass may occasionally be direct extension of the primary tumor rather than adenopathy. Imaging is essential for clarification of these issues.

Pathophysiology and Patterns of Disease

Pathology

More than 95% of malignant hypopharyngeal tumors are SCCAs. There is a tendency for cancers in this region to show carcinoma in situ at and frequently as much as 5 to 10 mm below surgical margins and well beyond grossly obvious mucosal margins (Figs. 219.6, 219.9, and 219.10). Skip areas of carcinoma in situ may make it difficult to obtain clear margins.

Minor salivary gland tumors are rare. Adenoid cystic carcinoma is likely the most common of these rare epithelial carcinomas arising in the lower pharynx and tracheal junction region. Sarcomas, metastases, and lymphoma are even rarer.

Patterns of Spread

Generally, tumor growth in the hypopharynx is directed by existing natural anatomic barriers. A tumor margin may be infiltrative or have pushing, well-defined borders (Chapters 21 and 23). There is a tendency for tumor to remain, at least for a time, confined to its area of origin. However, there is no real anatomic barrier that restricts spread from one area to the next.

CT and MR are very useful for evaluating some specific growth patterns of interest in medical decision making. The majority of pyriform sinus carcinomas are advanced at presentation. Even cancers that appear to be relatively limited clinically will frequently have gross involvement of the laryngeal framework and show extralaryngeal spread when imaged (Figs. 219.6–219.10). There is often submucosal spread well beyond visible mucosal margins. Invasion of the laryngeal skeleton and extralaryngeal spread (Figs. 219.6 and 219.7) occurs mainly in pyriform sinus primary tumors.

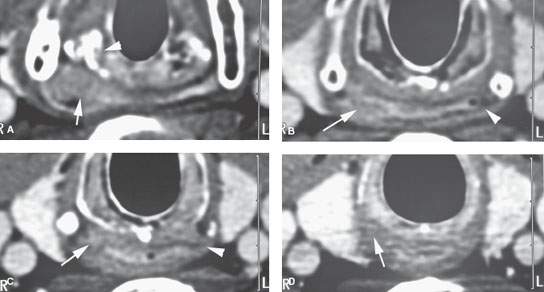

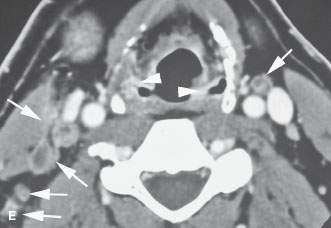

FIGURE 219.10. A patient with a limited tumor of the postcricoid portion of the hypopharynx beginning just below the pyriform sinus apex. A: Contrast-enhanced computed tomography study showing the area of most tumor bulk (arrow) just posterior to the cricoarytenoid joint just at and below the pyriform sinus apex. B: Infiltrating tumor predominately along the posterior wall of the mid postcricoid region (arrow) compared to the normal muscular wall on the opposite side. C: The lower aspect of the tumor is seen on the right side (arrow) compared to the normal side at the esophageal verge. D: The tissue planes have returned to near normal with only a minimal suggestion of tumor at the uppermost portion of the cervical esophagus. (NOTE: The patient required a partial upper esophagectomy to clear the lower limit of the tumor, and the extent of tumor as seen on this study was confirmed.) E: This patient also had multiple metastatic nodes bilaterally in levels 3 and 5B (arrows). This pattern of adenopathy is a very unusual pattern of spread for the postcricoid cancer shown in (A) through (D). There are multiple areas of mucosal enhancement throughout the hypopharynx. This proved to be due to multiple areas of dysplasia and early infiltrating carcinomas. (NOTE: Two issues are raised by the image in [E]. One is the concept of field “cancerization,” where patients with chronic tobacco and alcohol exposure of the pharynx have a risk of multiple tumors. The second concept is that if a pattern of adenopathy is atypical for the assumed primary source, then another second primary site should be considered likely and a search made for that source.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree