and A. Orlando Ortiz2

(1)

Department of Pathology, Winthrop-University Hospital, Mineola, NY, USA

(2)

Department of Radiology, Winthrop-University Hospitall, Mineola, NY, USA

Keywords

Bone neoplasms: chondrosarcoma, chordoma, giant cell tumor, lymphoma, metastases HistopathologySpine infectionStains: hematoxylin-eosin, immunohistochemical11.1 Introduction

A biopsy procedure does not necessarily start and end with the performance of the procedure. The objective of a biopsy is to obtain pathologic tissue in a sufficient amount so as to enable a pathologist and/or a microbiologist to make the diagnosis. The assumption that all that is necessary is to provide them with a specimen and that they will make the diagnosis can be equated with the request for an imaging study and the typical poor/vague history that presents itself at the radiologist’s reading station. Neither of these scenarios results in excellent medical care.

11.2 What Does the Operator Expect from the Pathologist?

Prior to an image-guided percutaneous spine or rib biopsy procedure, the operator may be considering a specific pathologic diagnosis based upon the patient’s imaging examinations and clinical presentation. At this time, the operator may want to discuss the case with the pathologist to determine how to proceed with the biopsy procedure. For example, if the operator is concerned about spine infection, then the majority of the specimen may be sent to microbiology. If the operator is suspecting lymphoma, then the specimen may be prepared for flow cytometry. A special stain may be required based upon the suspected pathologic diagnosis. The operator can also review the imaging findings with the pathologist, and this will in turn assist the pathologist in their subsequent analysis of the biopsy specimens. During the procedure, the pathologist’s assistance can be quite valuable. The presence of a pathologist is particularly helpful when assessing FNA samples for specimen adequacy and for cytologic diagnosis. After the procedure, the pathologist owns the major responsibility of trying to make the correct diagnosis. It may be helpful in certain instances for the operator to review the slides and images with the pathologist.

11.3 What Does the Pathologist Expect from the Operator?

A spine or rib biopsy procedure is requested. This presents the operator with significant opportunities to discuss the case not only with the clinician but also with the pathologist and microbiologist. There may be special circumstances when the operator should discuss the case with the pathologist or microbiologist prior to the procedure. It is important for the operator to not only communicate with these clinical associates after the biopsy procedure, not just to get the results, but prior to the procedure in order to optimize the results. The pathologist may want to discuss the case with the operator in order to obtain more clinical information. The operator should inform the pathologist if the patient has undergone any prior biopsies or surgeries and at which institution or facility these were performed. This will improve the pathologist’s chances of establishing the correct diagnosis. Similarly, the microbiologist should be informed whether or not the patient is being treated with antibiotics and, if so, which ones and for how long. Providing adequate clinical and radiologic information is also helpful to the pathologist. It is sometimes beneficial for the pathologist to review the prior imaging studies with the operator in order to assist in optimal biopsy planning. For instance, it is helpful for the pathologist to know if the lesion is lytic, cystic, solid, or enhancing. A radiologic differential diagnosis is quite useful and should be provided to the pathologist. If the operator suspects a specific diagnosis based upon a pathognomonic radiologic presentation, then the pathologist should be informed (Fig. 11.1).

Fig. 11.1

An 18-year-old male with nocturnal low back pain (same patient as in Fig. 12 in Chap. 6). Axial CT image in bone window algorithm (a) shows a small, well-circumscribed hypodense lesion within a sclerotic right lumbar pedicle (arrow); the lesion contains a small central mixed density nidus. Close-up photograph of biopsy specimen (b) shows red-brown bone core (arrow). Photomicrograph with H/E stain (c) shows circumscribed area of disorganized, sclerosed bone with marrow fibrosis. The histologic findings were consistent with an osteoid osteoma

Diagnostic tissue is best obtained from the non-necrotic component of a given lesion (Omura et al. 2011). After all, the goal of an image-guided percutaneous spine or rib biopsy procedure is to obtain specimen. The optimum biopsy procedure should yield as much tissue from the pathologic structure or region as possible. FNA is suitable for rapid answers in lesions that are easily biopsied using needle aspiration (Fig. 11.2) (Gupta et al. 2002). Cohesive or fibrous lesions may not be easily aspirated (e.g., schwannoma or fibrosarcoma). The small amount of tissue from FNA may not be sufficient for special studies including immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry, or molecular studies. The size of the needle that is used or additional FNA passes in order to obtain more tissue can alleviate this concern (Kreula 1990). Fine-needle aspirates are submitted in 50% alcohol. FNAs can be also performed during some bone biopsy procedures (Schweitzer et al. 1996). For FNA procedures, small cell clusters from the tissue that is sampled are desirable. The objective is to avoid contamination of the FNA sample with the patient’s blood. It is difficult to detect an abnormal cell in a virtual “sea” of blood. For this reason, it is important to perform the FNA procedure prior to the core biopsy procedure, as the latter can of cause an intra-lesional hemorrhage of sufficient quantity so as to contaminate a subsequent FNA pass. Soft tissue cores generate a much larger sample of the lesion than FNA which enables the performance of special studies with fewer needle passes (Yang and Damron 2004). A soft tissue cutting needle can be useful for lytic lesions. Small lesions require a short needle “throw” or excursion, while larger lesions can accommodate a longer needle “throw.” The pathologist is looking for as much tissue as possible from the soft tissue components of a given lesion. That being said, at least 2 mm in each dimension is preferred. Large bone cores by increasing the volume and area of sampling are desirable (Ortiz et al. 2010). However, the larger needle size and diagnostic benefit of larger specimens must be balanced against the increased risk of procedure-related hemorrhage. Tissue cores are submitted in 10% formalin. When performing bone biopsies, the operator must try to not only obtain as many bone cores as possible but also to handle the specimens as carefully as possible. This applies to transferring the specimen from the bone biopsy cannula into the transport media. Crush artifact may be created when obtaining core specimens, and this can cause diagnostic dilemmas. The likelihood of crush artifact can be reduced by trying not to impact the bone biopsy needle with one single specimen. Some lytic osseous lesions are very soft, and an FNA or soft tissue core biopsy may need to be performed in order to obtain a specimen. In certain situations, the only specimen that can be obtained is an aspirate of bloody material. This specimen should not be discarded and should be analyzed for the presence of neoplastic cells.

Fig. 11.2

Photograph (a) of a dual-viewer microscope that is located within the procedure area. This enables the cytotechnologist and pathologist to immediately confirm the absence or presence of a diagnostic FNA specimen. Photograph (b) of rapid staining agents that allow the cytotechnologist or pathologist to quickly process an FNA specimen and air-dry the slides. The slides can be prepared and reviewed within a few minutes. This technology contributes to the efficiency and safety of the biopsy procedure. A specimen cup (arrow) is kept on standby for any core biopsy material. Furthermore, the operator can directly convey additional information to the pathology department at the time of the biopsy

Always try to perform the FNA procedure prior to the core biopsy procedure.

11.4 Special Situations

Specimens for flow cytometry to diagnose lymphoma are submitted fresh on ice as quickly as possible to the lab, preferably early in the day to allow for specimen handling. FNA specimens that cannot be immediately assessed by the pathologist can be placed in an alcohol-based transport medium. If there is a concern for an inflammatory process such as gout, the specimen can be placed on a small piece of non-adherent dressing that is soaked in normal saline (Fig. 11.3). Infection is best verified by Gram stain and culture (Howard et al. 1994). Bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial cultures should be submitted directly to the microbiology department separately from the specimen submitted for tissue processing. An operator ought to consider sending specimens to both microbiology and pathology for analysis for lesions that involve multiple spinal levels and/or when the clinical and laboratory parameters (white blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein) are abnormal. Another clinical scenario in which both types of analyses should be performed is in patients who are immunocompromised.

Fig. 11.3

Photograph (a) of non-adherent dressing (arrow) and 10 mL normal saline. The scissors are used to cut a small piece from the pad and place the small piece of the pad within the sealable container. The normal saline is used to soak the non-adherent dressing. Photograph (b) of saline-soaked non-adherent dressing (arrow) within a sealed container. A specimen core (curved arrow) has been placed on top of the non-adherent dressing; this was submitted to assess for urate crystals

11.5 Optimizing Specimen Volume and Transport Media

One of the most deflating reports to receive, after a spine or rib biopsy procedure, often reads as one of the following:

It must be understood that this biopsy result can occur with any biopsy procedure (Hwang et al. 2011). Hence, pre-procedure disclosure to the patient about the possibility of a nondiagnostic biopsy should always be discussed. This will prevent the patient from becoming frustrated or disappointed if the result of the procedure is less than what was expected. The patient will also be aware that they may require another biopsy procedure. The biopsy procedure represents sampling of a small portion of a spine or rib lesion. If there is scant tissue within the sampled volume, then the likelihood of achieving a pathologic diagnosis is reduced. If the lesion is not completely sampled or not sampled at all, then the possibility of a confirmatory diagnosis is reduced (Figs. 11.4 and 11.5). Even more frustrating is the improper handling of specimens from the time of their acquisition (e.g., placing the specimen in the wrong transport medium) to the time of transport and delivery (the specimen is lost).

“Non-diagnostic specimen. Blood only in smears. Cell block shows minute fragments of benign cartilage and benign cortical bone. No marrow elements are present in the smears or cell block.”

Or

“QNS: quantity not sufficient for diagnosis.”

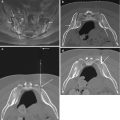

Fig. 11.4

A 58-year-old male with T12 bone lesion. Fat-suppressed contrast-enhanced T1-weighted axial image (a) shows large enhancing lesion (arrow) that contains several large necrotic or cystic foci (curved arrows). Axial CT image (b) with skin grid in place shows a subtle lesion (arrows). CT-guided coaxial biopsy (c, d) using costovertebral approach shows biopsy needle at the margin of lesion (arrows). An FNA (e) was then performed (arrow). The procedure yielded three bone cores and one FNA specimen. The FNA specimen (f) was nondiagnostic with only blood present on the smears. That the latter showed only blood is no surprise as the FNA was performed after the bone biopsy. Moreover, if the needle tip is within the vertebral marrow, blood will be aspirated (think of the vertebral body as a large trabeculated venous structure with marrow elements). The cell block (g), which was obtained from the bone cores, showed only minute fragments of calcified tissue (arrow), most likely representing the bone. In this case, the peripheral location of the biopsy needle relative to the center or “meat” of the lesion may account for this nondiagnostic biopsy. A steeper approach to the lesion would have yielded access to the epicenter of the lesion with the possibility of a diagnostic biopsy

Fig. 11.5

An 86-year-old male with prior history of asbestos exposure presents with focal left pleural thickening and a rib lesion. Axial CT image (a) shows FNA (arrow) of extraosseous soft tissue component. The results of this biopsy were negative for malignant cells and consisted of a relatively hypocellular specimen. The patient returned 7 months later for a repeat biopsy. Axial CT image (b) shows a marked increase in the size of the rib lesion (arrow) and its extraosseous extension (small arrows). A guide needle (curved arrow) is in place for FNA. The repeat biopsy consisted of two FNA touch preps which showed the presence of sheets of atypical plasma cells (c) with numerous Dutcher bodies (arrows). Immunoperoxidase stains that were performed on the cell block, from the soft tissue biopsy cores, included a positive kappa stain (d). The immunoprofile excluded malignant mesothelioma and was consistent with a plasmacytoma with kappa restriction

The goals then are to maximize the amount of pathologic tissue that can be reasonably acquired during the biopsy procedure, to place the harvested material in the appropriate labeled specimen containers, and to expeditiously transport these containers to the appropriate destinations for processing and analysis. Limited specimen volume due to small gauge sampling devices may be an issue. At times the operator may not have a choice in this matter due to factors such as small lesion size or a suspected hypervascular lesion. Small lesions may limit the number and size of specimen samples. Whenever possible, the use of larger-gauge needles enables the operator to harvest more specimens (Fig. 11.6). This translates into better statistical sampling of the lesion with a higher likelihood of obtaining diagnostic tissue. The most useful pathology information is obtained from biopsy samples that include at least one core of bone or soft tissue. In order to optimize pathologic evaluation and diagnosis, it is best to submit as many cores as possible (Wu et al. 2008). At least three bone cores, if possible, should be obtained and placed in 10% formalin for submission to pathology. Of note, bone biopsy specimens must undergo a 48-h period of decalcification in 7% formic acid prior to sectioning and staining. Thus, it is important to obtain enough tissue such that an adequate amount remains after decalcification for histological analysis. Never discard marrow aspirates as these may harbor representative tissue from the lesion in question (Hewes et al. 1983). For soft tissue or lytic lesion soft tissue biopsies, at least four soft tissue cores, if possible, should be obtained; these also can be submitted in 10% formalin. The type of imaging guidance (i.e., CT vs. fluoroscopy) does not appear to be a factor in obtaining core samples and arriving at a pathologic diagnosis.