IMAGING GUIDED BIOPSY

KEY POINTS

- Imaging-guided biopsies can markedly influence medical decision making and can obviate much more complicated and potentially morbid open surgical methods.

- Proper planning is essential for the highest diagnostic yields.

- Such sampling is only marginally helpful in inflammatory conditions except to mainly to exclude tumor.

INDICATIONS

Clinical Perspective

The vast majority of biopsies in the ear, nose, and throat (ENT) region are done by clinicians under direct or endoscopic visualization with standard surgical instruments. Since the 1970s, head and neck surgeons and radiologists have continuously improved the skills necessary to perform percutaneous fine needle aspiration (FNA) and cutting needle (core) biopsies. Most of these procedures are done in the clinic or physician’s office on palpable and/or visible masses. Accurate cytologic and histologic evaluation of these samples is now routinely available at the time of the biopsy and is a requirement to determine the adequacy of the sample.1

Circumstances that require imaging guidance for needle biopsies include: (a) a mass apparent only on imaging studies that is not accessible to standard biopsy techniques, and the biopsy results would significantly alter patient management (Fig. 6.1); (b) the mass involves the deep spaces of the face near the skull base, and surgical approach for biopsy would be needlessly morbid and expensive (Fig. 6.2); (c) there is a significant risk that biopsy not guided by imaging would injure a major vessel or nerve; and (d) the patient is a poor candidate for general anesthesia and an operative approach for tissue sampling.

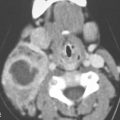

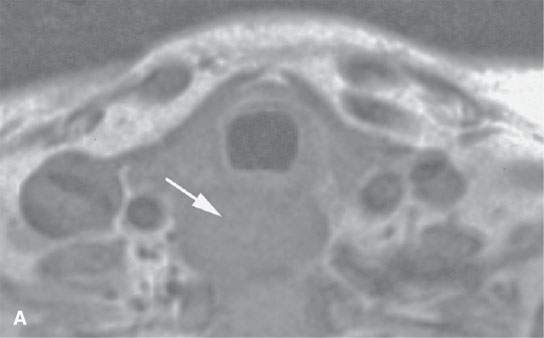

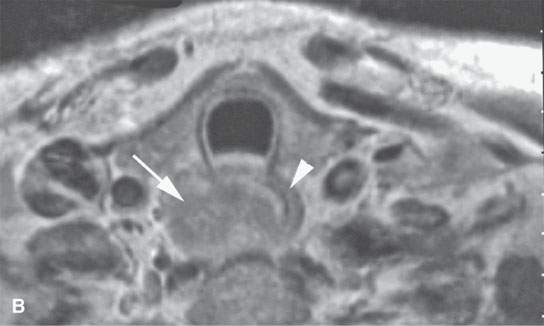

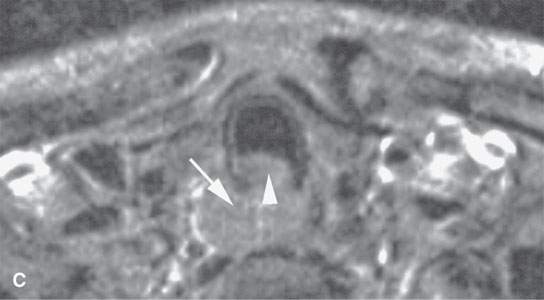

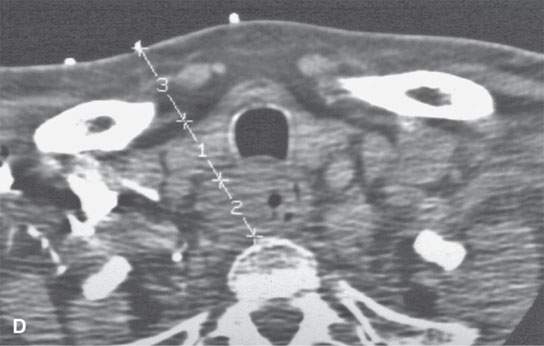

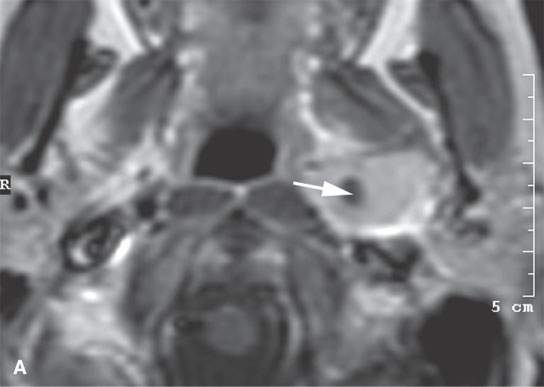

FIGURE 6.1. A patient presenting with dysphagia. This magnetic resonance imaging study was obtained. A: T1-weighted non–contrast-enhanced image showing enlargement of the esophagus, especially on the right side (arrow). B: T1-weighted image following contrast injection showing an infiltrating mass clearly involving the right side of the cervical esophagus (compared to the more normal muscular wall on the left (arrowhead). C: T2-weighted image confirming the mass of lesser than muscle intensity involving the cervical esophagus (arrows) and the common wall between the trachea and esophagus (arrowhead). D, E: Target planning and needle placement images of a computed tomography (CT)-directed biopsy. Needle biopsy returned squamous cell carcinoma (SCCA). (NOTE: This patient had two complete endoscopic procedures including definitive esophagoscopy by very experienced endoscopists. Neither showed a mucosal lesion. The second included biopsies of the cervical esophagus directed by the magnetic resonance findings; those biopsies were negative. Percutaneous CT was necessary to confirm the presence of an entirely submucosal esophageal SCCA.)

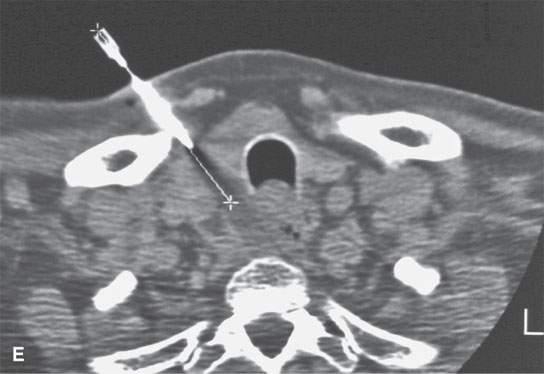

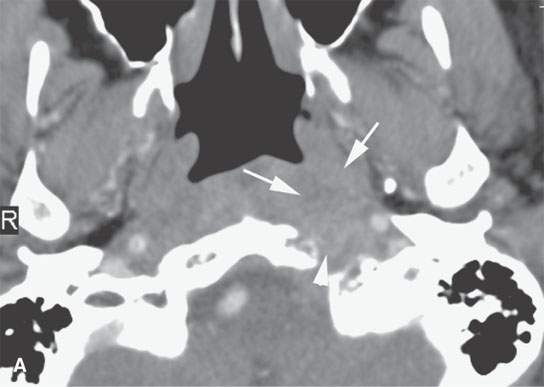

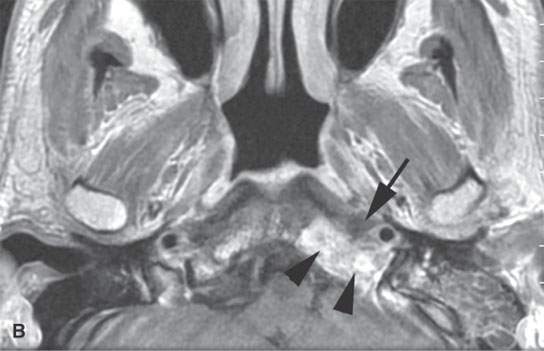

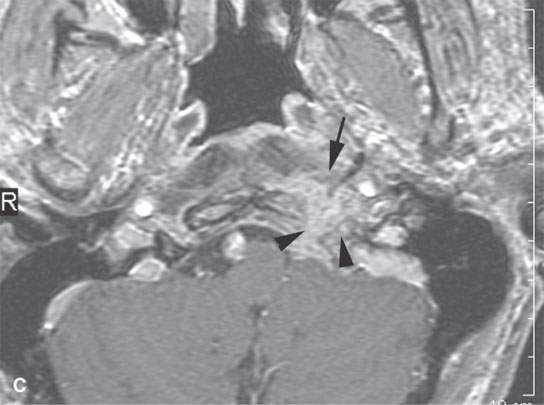

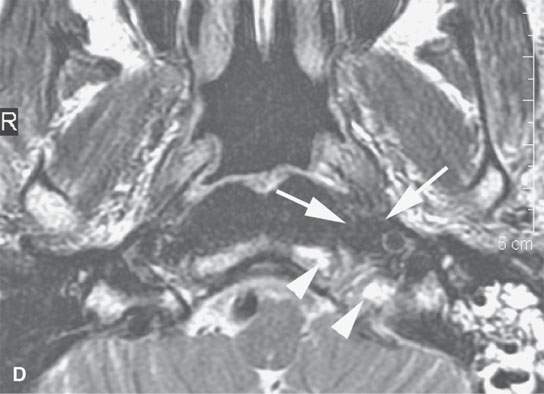

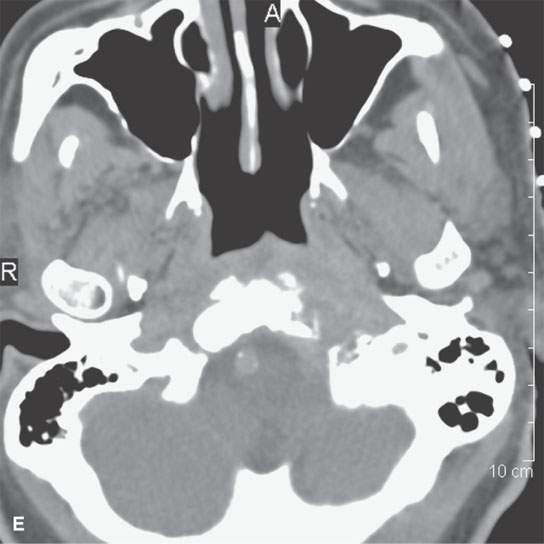

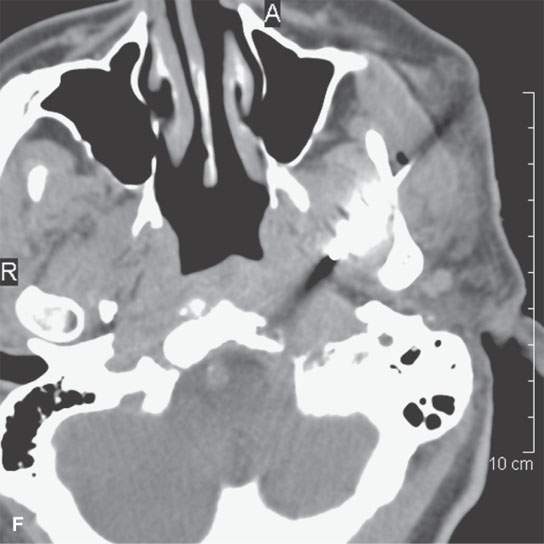

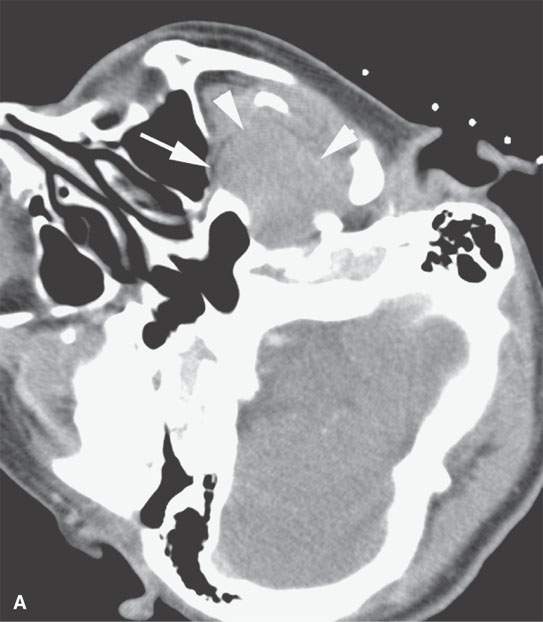

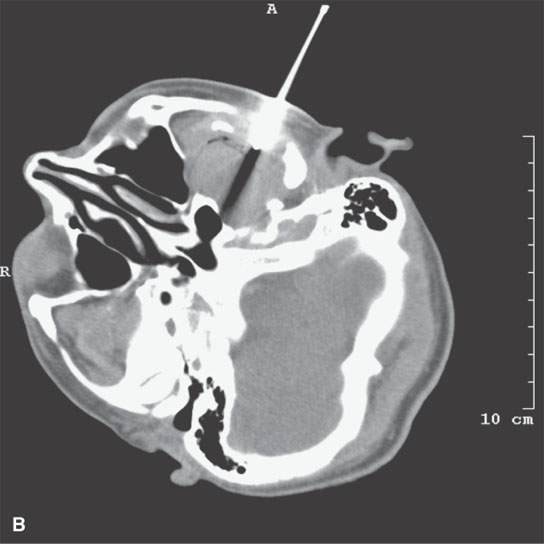

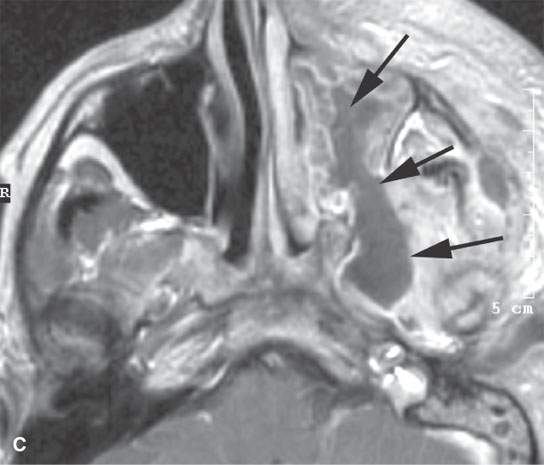

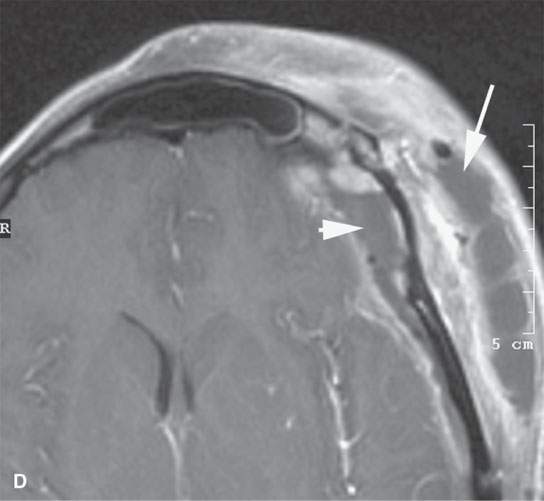

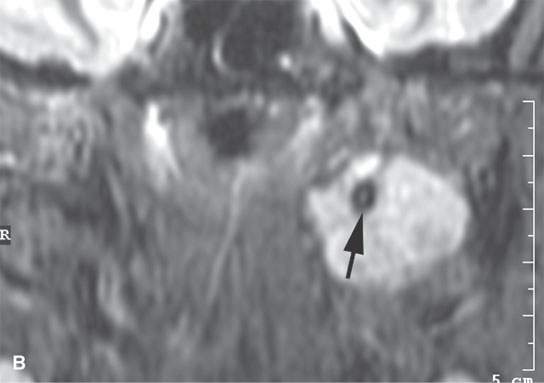

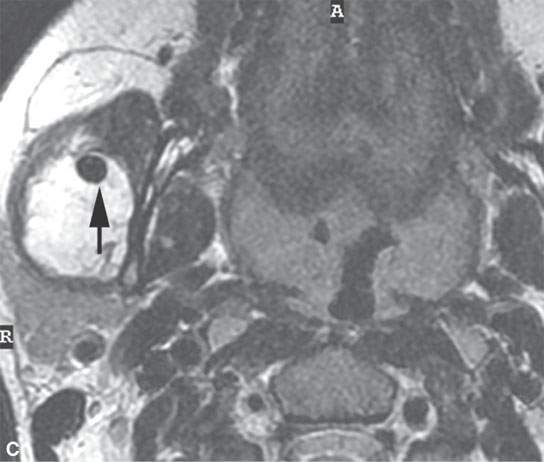

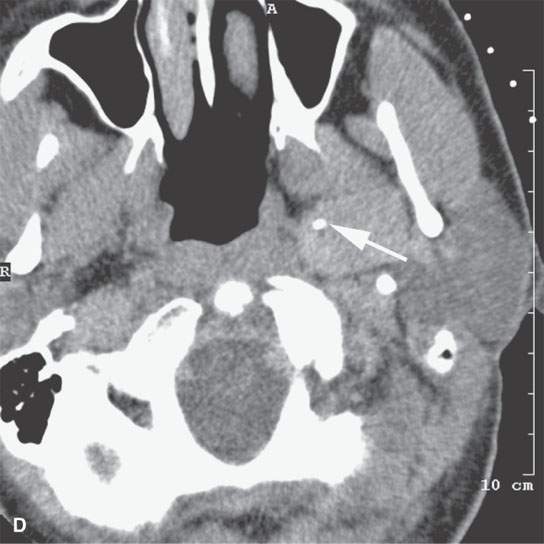

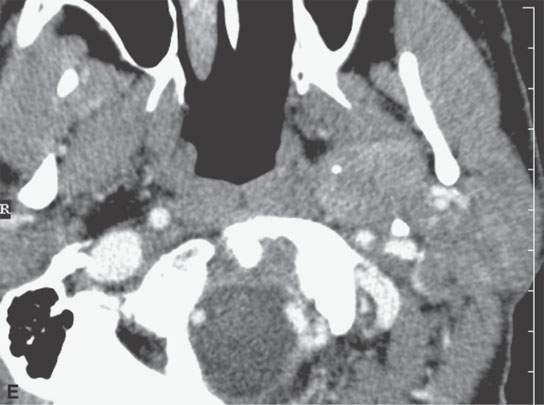

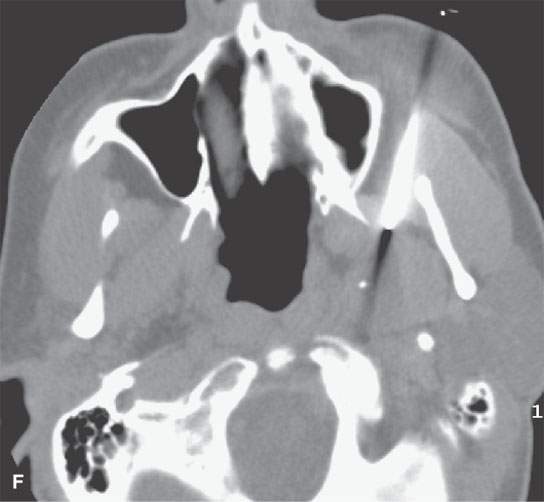

FIGURE 6.2. A patient presenting with otalgia and cranial nerve X deficit on the left. Diagnostic computed tomography (CT) showed a causative mass. Endoscopy with biopsy was negative. Further surgical approach to the area of suspicion involving the skull base and nasopharynx would have been prohibitively extensive. A decision was made to do a CT-guided biopsy. A: Diagnostic contrast-enhanced CT shows an infiltrating mass (arrows), possibly of nasopharyngeal origin but also possibly arising from the skull base where there is fairly extensive skull base erosion (arrowhead). B: Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was done to evaluate the full extent of the lesion and to plan the most appropriate target. T1-weighted images following contrast enhancement in (B) and (C) showed an infiltrating mass that appeared to be more centered in the skull base (arrowheads) with overlying reactive nonenhancing tissue (arrow). C: T2-weighted image again showed that tissue within the skull base (arrowheads) was much more likely to yield a positive biopsy than the overlying tissue lower in signal intensity (arrows) equivalent to muscle. (NOTE: The low-intensity tissue was felt to represent reactive changes to tumor rather than tissue that would likely yield a definitive diagnosis. In this manner, MRI was used to choose the most appropriate target; CT was nonspecific in this regard.) D: Planning CT examination shows markers in place on the skin. E: Image shows that the approach was subzygomatic via the mandibular notch. Biopsy returned squamous cell carcinoma that was felt to be primary in the nasopharynx.

The majority of imaging-guided head and neck biopsies other than those of the thyroid are requested by the attending head and neck surgeons. Some requests are initiated by the radiology department for the most logical means of definitive diagnosis based on the original interpretation of diagnostic studies. Any imaging practice with a heavy ENT referral pattern will be asked to perform a relatively high number of computed tomography (CT)-guided biopsies of deep face processes. An even larger number of imaging-guided biopsy requests are likely if there is an active referral base of ultrasound thyroid nodule evaluation. The head and neck guided biopsy procedures are, relative to other body regions, infrequent. Potential risks such as carotid injury seem considerable, but in fact it is far safer to do these biopsies than those of the lung or liver. The key to safety and success is careful planning.

Head and neck abscesses are still mainly drained by open operative procedures. These can be managed by percutaneous imaging-guided techniques if desired; however, this is not a commonly offered procedure in radiology departments, and a very close relationship between radiologists and the referring clinical service is required.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

There are few, if any, absolute contraindications to these techniques. Biopsy with large-bore needles in patients who are at risk for hemorrhage, on the basis of a noncorrectable medical condition, should be avoided as a relative contraindication. In this situation, the relative risk of bleeding from a 23- to 25-gauge needle attempt at aspiration would need to be weighed. If the smaller-needle sampling were not successful, then the needle size could be increased, again weighing the risk by assessing the effects of the thinner-needle approach with respect to the amount of procedural bleeding encountered.

The usual precautions with regard to contrast and medication sensitivities must be taken into account in procedure planning, but these will rarely obviate an attempted procedure.

If the biopsy would potentially put the airway at risk, a person capable of managing the airway needs to be immediately available to manage such a complication. This circumstance arises mainly in conjunction with laryngeal biopsies (Fig. 6.3) but must be considered in all cases, especially those where there is initial airway compromise by the lesion being biopsied.

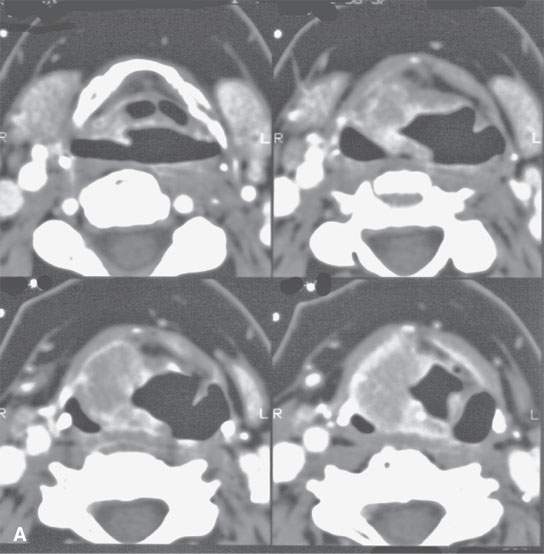

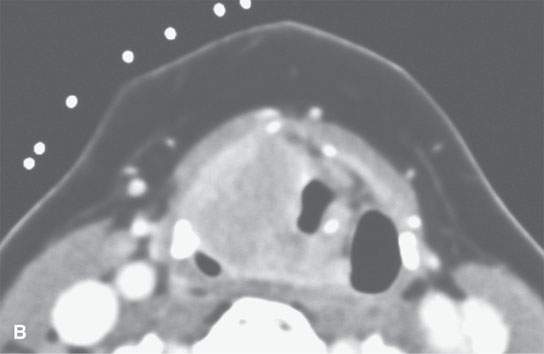

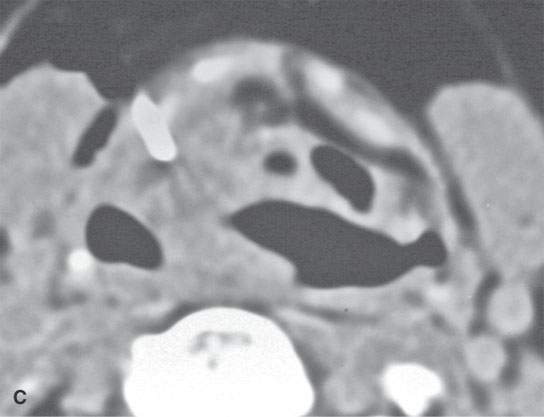

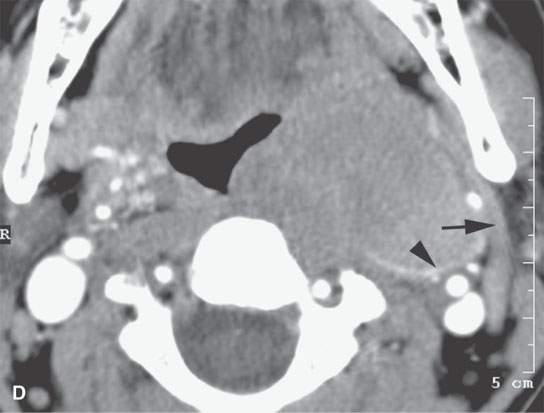

FIGURE 6.3. A patient with hoarseness and several endoscopic exams that show no laryngeal mucosal lesion. The patient’s history had been going on for approximately 2 years. A: Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) study showing an entirely submucosal enhancing mass in the right paraglottic space. B: CECT study with markers in place to plan approach. The submucosal mass narrows the airway considerably. The otolaryngology service was on site to manage an airway complication should one have occurred. C: Biopsy needle in place. The biopsy returned squamous cell carcinoma. D: A second patient presenting with airway compromise due to mass in the parapharyngeal space. CECT study showed the mass to be localized to the retrostyloid parapharyngeal space based on the displacement of the styloid musculature (arrow) and its mass effect on the carotid sheath (arrowhead). Because of the localization, a lesion such as a neurogenic tumor or sarcoma was considered likely. In this instance, it is preferred to use core needle sampling to increase definitive diagnostic yield. Because of the pre-existing symptomatic airway compromise and the plan to use core biopsy sampling, the otolaryngology service placed a tracheostomy before the procedure.

EQUIPMENT (OPTIMAL AND INCLUDING CONTRASTS)

Hawkins blunt needles should be available for initial approach and engagement of some lesions. Otherwise, standard biopsy needles used for both core and aspiration sampling as preferred by the individual operator are appropriate. For core biopsies, either an attachable spring-loaded biopsy gun or a self-contained spring-loaded system for sampling is preferable to manual systems. With core biopsy systems, it is useful to have multiple gauges, lengths, and throw distances available.

Special ultrasound transducers adapted for biopsy can be used, but in reality most ultrasound-directed biopsies are done freehanded. Stereotactic frames and mechanical arms are generally not used. These may prove useful in the future, as smaller and deeper lesions become targets for imaging-assisted ablation.

TECHNIQUE APPROACHES

Planning

All imaging-guided biopsies should follow a standard protocol. The following suggested planning steps (1 through 5) are best done as a consultation service before the patient is scheduled.

(1) Direct verbal consultation with the referring physician to:

- Obtain an accurate pertinent history, physical findings, and potential impact of the biopsy on management;

- Determine if more reasonable or potentially higher-yield surgical alternatives to imaging-directed biopsy are available; and

- Help decide whether cytology (Figs. 6.1, 1.6, and 2.6) will be adequate for disposition or whether core samples (Fig. 6.4) or samples suitable for flow cytometry (Fig. 6.4) are likely to be necessary.

FIGURE 6.4. This study illustrates how percutaneous guided biopsies as opposed to open surgical approaches might help avoid operative complications. This patient presented with left facial pain. Imaging showed a transcranial mass with a significant component in the infratemporal fossa on the left. A: The mass bulged into the posterior superior aspect of the maxillary sinus (arrow) and filled the masticator space (arrowheads). B: An immediately subzygomatic approach was taken to this mass. The mass was aspirated, not cored. Needle aspiration biopsy was not definitive. (NOTE: Masticator space masses are likely to be a sarcoma, meningioma, or neurogenic tumors, all likely to only be definitively diagnosed from core samples.) Since that aspiration biopsy was not successful, the patient was biopsied by an open procedure through the posterior wall of the maxillary sinus, and a diagnosis of aggressive meningioma was made. The patient went on to definitive surgical resection but came back about 2 weeks after surgery with fever and extensive facial pain and swelling. C, D: There is an infected maxillary sinus with a track from the sinus likely along the original biopsy path into the infratemporal fossa (arrows). This collection of purulent material was in continuity with a very extensive deep scalp abscess (arrow) and epidural abscess (arrowhead). (NOTE: Had an appropriate choice to use core technique rather than aspiration for cytologic evaluation been made, the postoperative infection might have been avoided. It is possible that the tract created by the biopsy was the path for the postoperative infection. That biopsy might not have been necessary if adequate core samples produced an appropriate histologic diagnosis from the percutaneous computed tomography–guided procedure.)

(2) Review all imaging studies available to help plan the target and approach and determine if additional prebiopsy studies are necessary (Fig. 6.5).

FIGURE 6.5. Careful analysis of imaging studies prior to approach is essential. This patient had an incidentally discovered parapharyngeal mass. It was found on a magnetic resonance (MR) study done for headaches. A: T1-weighted, contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) shows an enhancing mass with a focal round signal void (arrow) that was felt to possibly represent a phlebolith, as might be seen in a slow flow vascular malformation. B: T2-weighted image confirmed the round signal void (arrow) within a homogeneously bright lesion. Statistically, this should just be calcification in a benign mixed tumor. However, core needle techniques might have been desirable in this case. –C: Comparison masticator space venolymphatic malformation in a different patient to demonstrate the concern that the lesion seen in the parapharyngeal space might represent a venolymphatic malformation, in which case the use of a cutting needle would not be advisable. D, E: CECT studies done during an arterial and delayed type of data sampling. The calcification suspected on the MR, which looked somewhat like a phlebolith, was confirmed (arrow). The flow dynamics of the lesion did not strongly suggest that this was a venolymphatic malformation. F: The lesion was approached across the buccal space with a cutting needle. A benign mixed tumor was confirmed.

(3) Determine whether ultrasound, CT, or magnetic resonance (MR) will be used for guidance (Fig. 6.6).

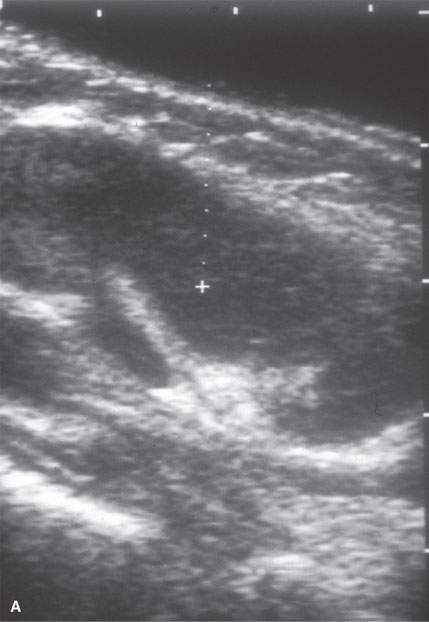

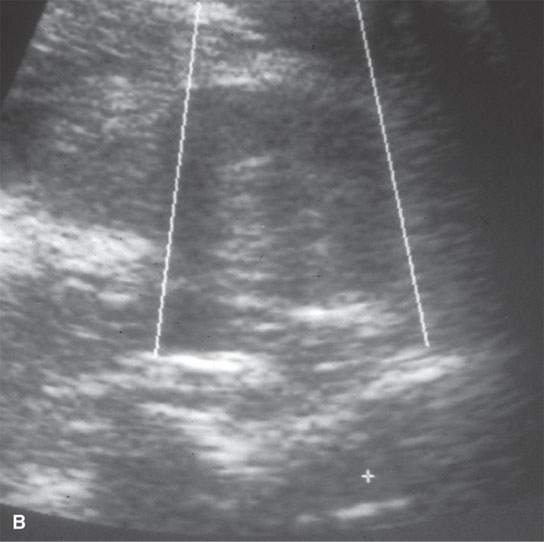

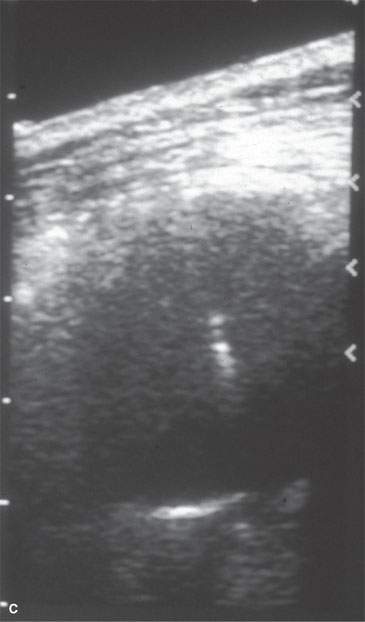

FIGURE 6.6. Many biopsies, especially of neck lesions, may be very simply and quickly done using ultrasound control. A: Ultrasound showing an enlarged neck node. The morphology is consistent with a reactive node or lymphoma. B: Axial image of a biopsy in progress, which in (C) confirms the needle placement within the node. Lymphoma was confirmed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree