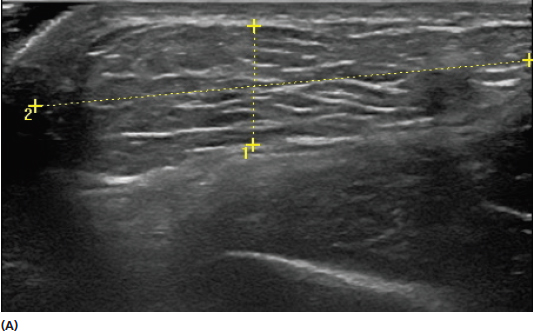

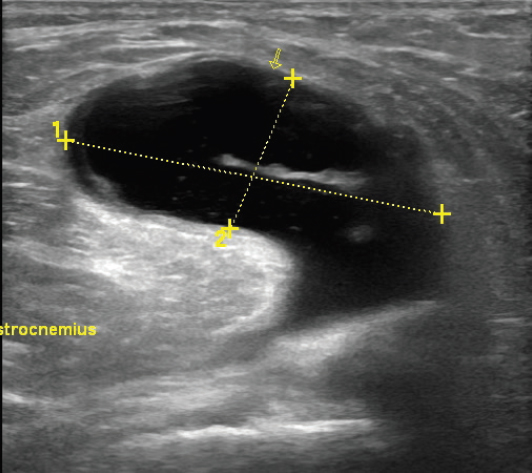

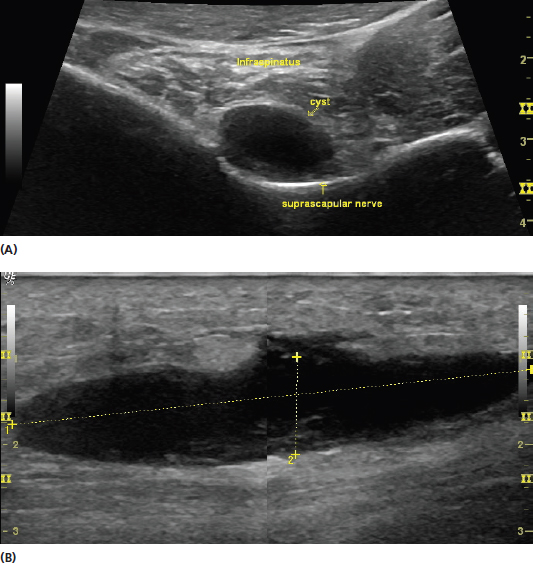

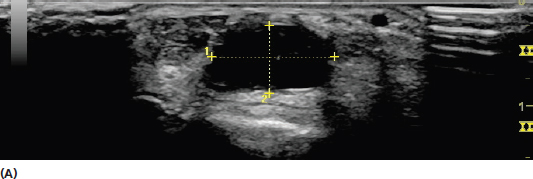

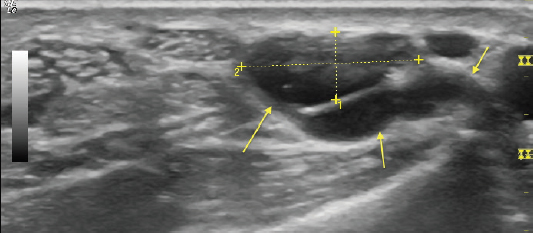

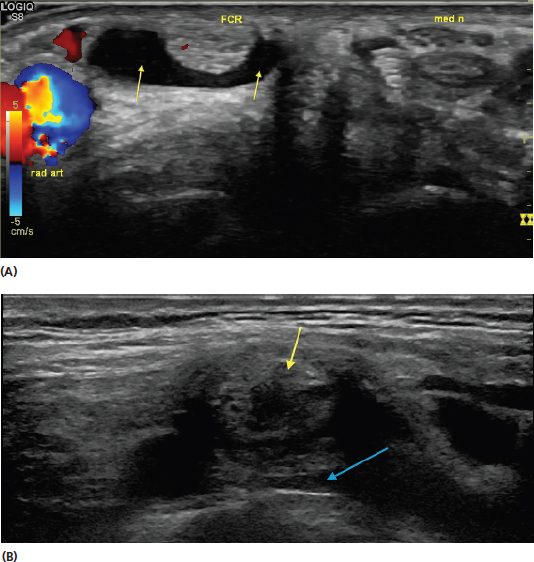

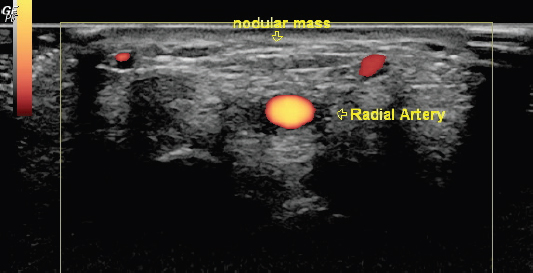

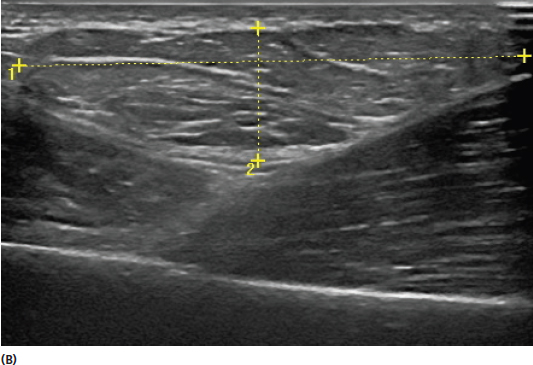

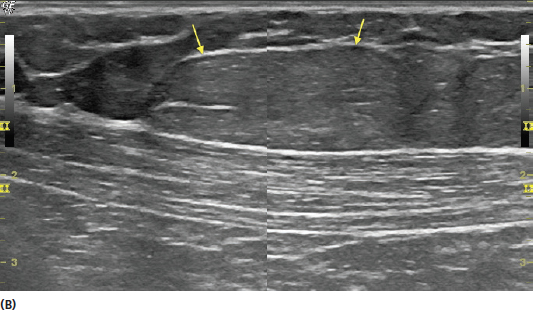

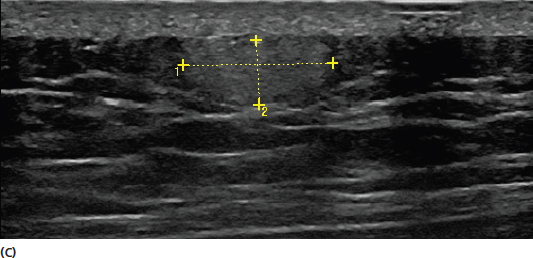

A systematic approach to masses is needed for anyone involved in musculoskeletal ultrasound. They can be encountered incidentally in routine examinations and frequently are the presenting complaint. A tissue diagnosis cannot be reliably determined on every ultrasound examination, but characteristic features can be distinguished that are often helpful for determination of the need for additional evaluation as well as management decisions. Some of these features include the size, nature of the border, echotexture, compressibility, relationship to surrounding tissue, and relative vascularity. Ultrasound is an excellent modality for measuring the size of a mass. Most ultrasound instruments can provide measurements that are accurate within fractions of a millimeter. Masses should be scanned in both short- and long-axis planes. It is typical to report the linear measurement of three orthogonal planes, referred by some as maximum length, width, and height (Figure 11.1). Care should be used to completely scan and identify the entirety of the mass. In cases in which the mass displays an irregular shape or border, and these parameters are difficult to reliably determine, this shape should be described and the relative size should be reported to the extent possible (Figure 11.2). Ultrasound also is an excellent, cost-effective modality for following progression of mass size, shape, and other characteristic changes over time. FIGURE 11.1 Sonograms demonstrating short-axis view (A) and long-axis view (B) of a superficial mass (lipoma) demonstrating use of linear measurement to assess the size. The length and width are obtained using the two views. The depth should be consistent between the two views. Note the difference in echotexture between the mass and both the superficial dermal layer and deeper muscle layer. FIGURE 11.2 Sonogram of an irregularly shaped mass (semimembranosus-medial gastrocnemius [Baker’s] cyst) that limits the precision of size determination with linear measurements. In such cases, the size is reported to the extent possible and the shape and other characteristics are included in the description. The characteristics of the border of masses often provide important clues of their nature and should be reported in the medical record. Masses with irregular borders often have different implications than those with smooth borders with well-defined walls (Figure 11.3). It should be noted when the mass appears contiguous with the surrounding tissue as opposed to having well-defined borders. The overall shape of the mass should also be considered and described. FIGURE 11.3 Sonograms demonstrating examples of different borders of otherwise similar appearing masses. The image in (A) displays a mass (cyst) with well-defined walls. The image in (B) has a similar echogenic appearance as the cyst but does not have a well-defined border over its entire circumference. This image represents a hematoma that lies within a fascial plane. Some of the fluid infiltrates the overlying tissue in an irregular pattern as a clue that it is not cystic. Note that this image is a split-screen approximation used to visualize the length in one picture. Additional consideration should be given to the location of the mass in relation to other tissue. Note that the cyst in image (A) is in proximity to the suprascapular nerve creating neuropathy as a result of mass effect. The nature of the echotexture of the mass should be considered. It should be described in relation to the surrounding tissue but also in reference to its own relative uniformity. The mass should be defined as hypo, hyper, or isoechoic relative to the structures around it (Figure 11.4). The echotexture can help determine if the mass is cystic or solid. The presence of any septations or divisions within the mass should also be noted (Figure 11.5). FIGURE 11.4 Sonograms demonstrating examples of masses with different echotextures. In (A), the mass is hypoechoic relative to the surrounding tissue. This particular mass is a ganglion cyst. In (B), the mass is relatively isoechoic relative to the surrounding subcutaneous tissue. This mass is a lipoma with echotexture similar to the surrounding adipose. Note that the echotexture is distinct from the underlying muscle layer. In (C), the mass is hyperechoic relative to the surrounding tissue. A mass with this echotexture often might require biopsy or excision for a specific tissue diagnosis. FIGURE 11.5 Sonogram demonstrating a mass (ganglion cyst) with multiple septations (yellow arrows). The relative compressibility of a mass can be determined by the amount of pressure exerted by the transducer. There is deformation of most soft tissue with increasing transducer pressure (Figure 5.3) but the extent of change of the mass relative to the surrounding structures can often be helpful. A cyst or vascular structure will typically deform with external pressure to a much greater extent than a solid mass. The location of the mass in relationship to other anatomic structures should be determined and reported as it can be a valuable clue toward determining the nature of the mass as well as its potential complications from occupying space. The proximity to tendons, joint spaces, and neurovascular bundles should be of particular emphasis. Any displacement of surrounding tissue should be identified [Figures 11.3(A) and 11.6]. It should be noted when the mass is infiltrating other tissue, which is more typical in malignant conditions. FIGURE 11.6 Sonograms demonstrating examples of mass effect on surrounding tissue from the mass. The image in (A) shows a short-axis view of a ganglion (yellow arrows) causing compression and discomfort on the distal flexor carpi radialis (FCR) tendon. Note also the location of the radial artery (rad art) and median nerve (med n). The image in (B) shows a view of a solid supraclavicular mass (yellow arrow) causing compression of the subclavian vein (blue arrow). Understanding the relationship of the mass to the surrounding tissue can sometimes provide insight into the patient’s clinical condition. Use of Doppler imaging is helpful for assessing the relative vascularity of a mass (Figure 11.7). Color Doppler is generally more effective for higher flow states and Power Doppler for identifying smaller vessels (see Chapter 6). Efforts should be made to distinguish if any vascularity is within the mass or external to it. Vascularity of a mass is more frequently seen with malignant conditions. This is not always a reliable parameter for distinguishing a benign from a malignant mass. Other imaging modalities and biopsy or referral for excision should be considered when further investigation is warranted. FIGURE 11.7 Sonogram demonstrating the use of Doppler imaging to assess the relative vascularity of a palpable mass. In this image, there are no signs of vascularity intrinsic to the mass but only extrinsic. 1) When assessing a mass, determine whether it is solid or cystic and whether the border is smooth or irregular. 2) Measure the size of the mass using the measurement tools on the ultrasound machine and use three orthogonal planes. 3) Determine if the mass invades surrounding tissue. 4) Use Doppler imaging to assess the vascularity of the mass. 5) Do not attempt to make a tissue diagnosis of the mass, particularly when inexperienced. Refer to other imaging modalities such as MRI and other assessment when appropriate.

Imaging Masses

DETERMINING SIZE

NATURE OF THE BORDER

ECHOTEXTURE

COMPRESSIBILITY

POSITIONAL RELATIONSHIP TO SURROUNDING TISSUE

RELATIVE VASCULARITY

REMEMBER

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree