INFECTIOUS AND NONINFECTIOUS INFLAMMATORY DISEASES: AUTOIMMUNE DISEASES AND AMYLOIDOSIS

KEY POINTS

- Autoimmune diseases, while systemic, often present with head and neck manifestations, and clues to the systemic nature of the disease rely on recognizing the general head and neck pattern of organ changes and bilateral involvement.

- Autoimmune diseases can mimic other systemic diseases such as sarcoidosis, Wegener granulomatosis, and lymphoma in their head and neck presentations and pathoanatomic patterns.

- Autoimmune diseases can sometime mimic localized diseases of the head and neck as diverse as necrotizing otitis externa, infectious sialoadenitis, and orbital pseudotumor, among others.

- The pathoanatomic pattern of any particular head and neck organ involvement is usually diffuse but can be focal.

- Autoimmune diseases may have significant intracranial as well as extracranial involvement.

- Intracranial disease may be expressed as manifestations of central nervous system vasculitis.

- Extracranial manifestations are often “multifocal” in the head and neck region.

Autoimmune diseases may affect various structures and organs in the head and neck. These head and neck manifestations can sometimes be the presenting complaint of an otherwise systemic disease or can be autoimmune disease localized to one or more anatomic head and neck sites. Autoimmune diseases affecting the brain are well known to neuroradiologists, as they are expressed as vasculitis with or without cerebral infarction and usually are due to complications and/or hypercoagulable states. These include, among others, antiphospholipid syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), periarteritis nodosa, and primary central nervous system (CNS) vasculitis. Other diseases such as neuromyelitis optica and multiple sclerosis are presumed by some to be autoimmune. Others such as autoimmune inner ear disease are known to be autoimmune but do not commonly express themselves on imaging studies. Most of these are well beyond the scope of this work but may be mentioned in conjunction with specific anatomic regions in the context of differential diagnosis.

The most common autoimmune diseases of the head and neck outside the CNS are manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and Sjögren disease or syndrome, Graves disease, and autoimmune or Hashimoto thyroiditis.1 These will be discussed in general here and more specifically in association with their particular sites of involvement.

Amyloidosis is discussed here since it may be due to an ongoing appropriate not but autoimmune response to a chronic inflammatory disease. Sometimes, the cause of amyloidosis is unknown.

SJÖGREN SYNDROME

Classically, a disease named keratoconjunctivitis sicca and xerostomia is a perfect description of this disease that affects about 3% of the population, as it causes dry eyes and a dry mouth.2

When seen in conjunction with other autoimmune diseases, it is called Sjögren disease. Those diseases include RA, SLE, scleroderma, and polymyositis, among others.

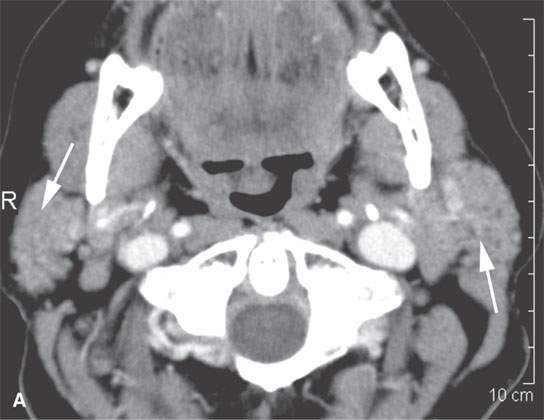

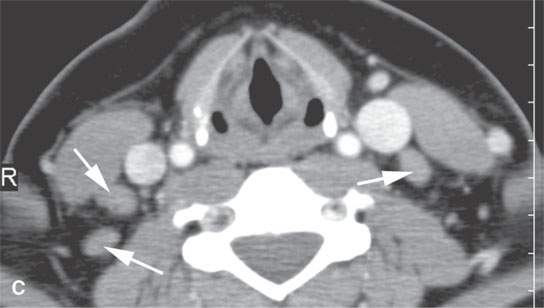

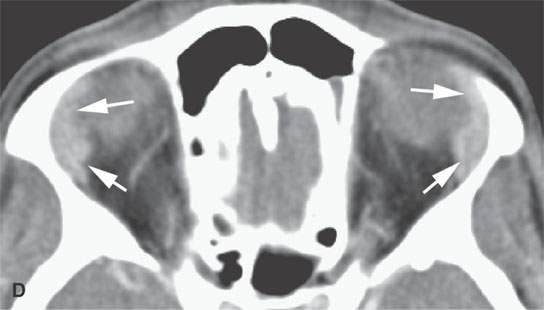

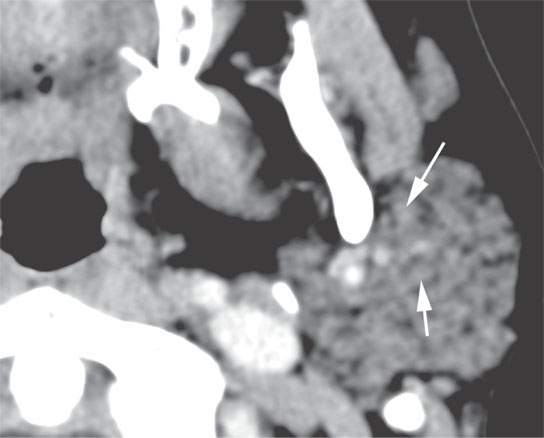

Its active state may cause swelling of all major salivary glands and the lacrimal glands (Figs. 20.1–20.4).3 This may be diffuse or multinodular. There may be ductal dilation, parenchymal cysts, and sialoliths present. Sjögren changes may also be encountered on head and neck imaging as an atrophic “end-stage” appearance of any or all of these structures as they shrink and become fat replaced, with their remaining parenchyma often appearing diffusely linear and nodular, especially the parotid glands (Figs. 20.5 and 20.6). In the involuting stage or active stage, the distribution and morphology of the disease can mimic sarcoidosis on imaging studies, but this easily is sorted out clinically.

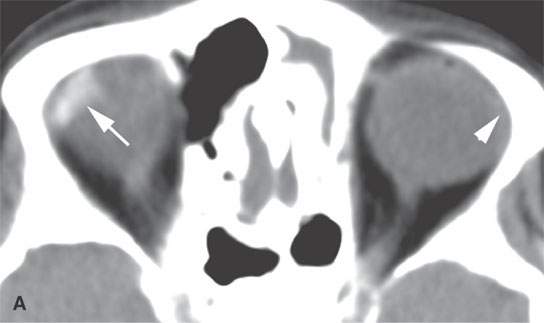

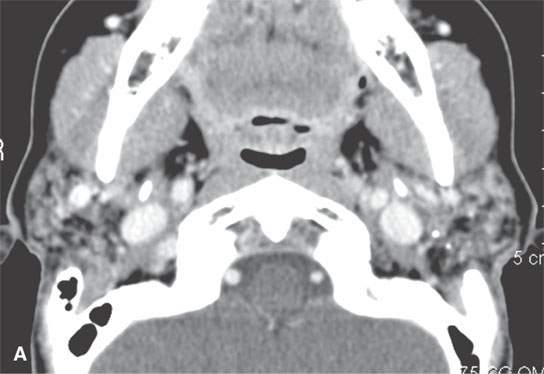

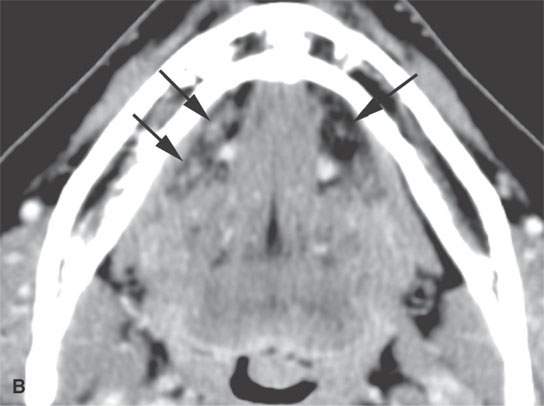

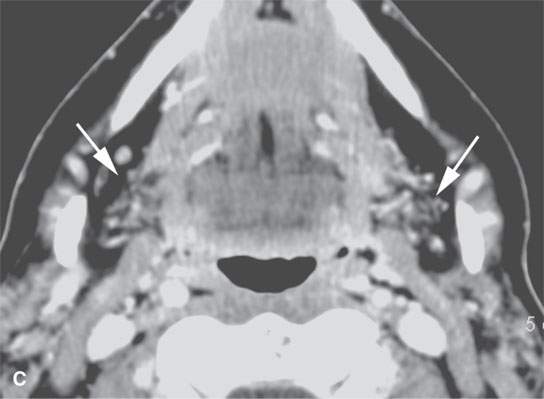

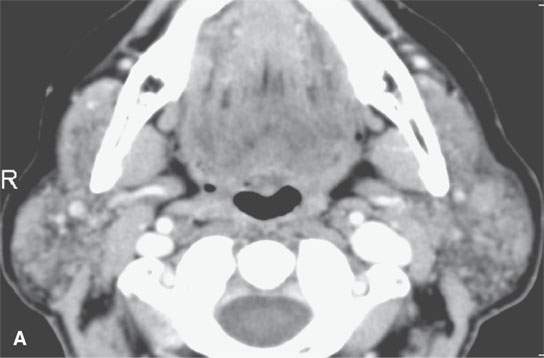

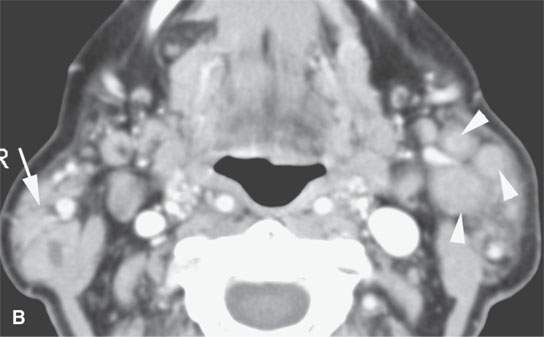

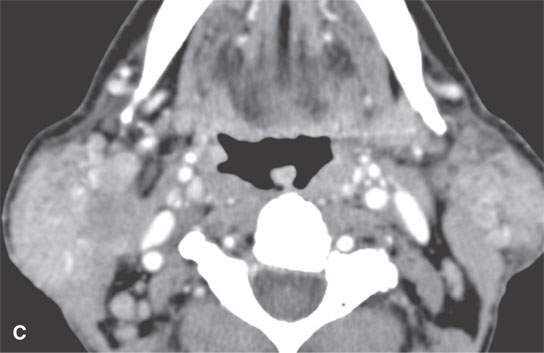

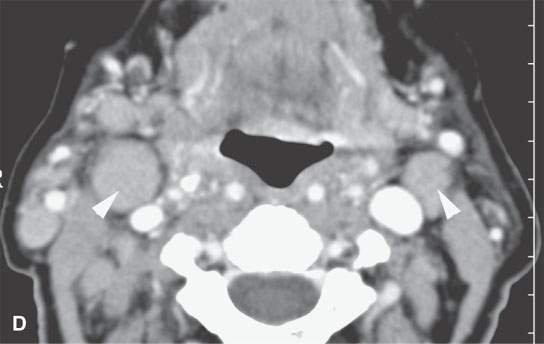

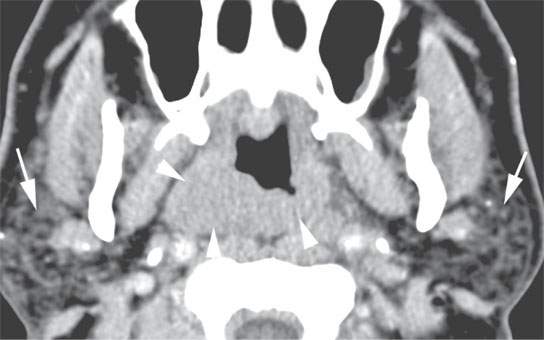

FIGURE 20.1. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography in a patient with chronic clinically active Sjögren disease shows enhancement and swelling of the parotid glands (arrows in A), atrophy of the submandibular glands (arrows in B), adenopathy (arrows in C), and slight enlargement and abnormal enhancement of the lacrimal glands (arrows in D).

FIGURE 20.2. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography shows nonenhancing nodularity in the parotid gland that can be seen in autoimmune disease, such as in this patient with Sjögren syndrome. The pattern is nonspecific and can be seen in sarcoidosis and chronic recurrent infectious parotitis. This degree of nodularity usually is not a normal variation.

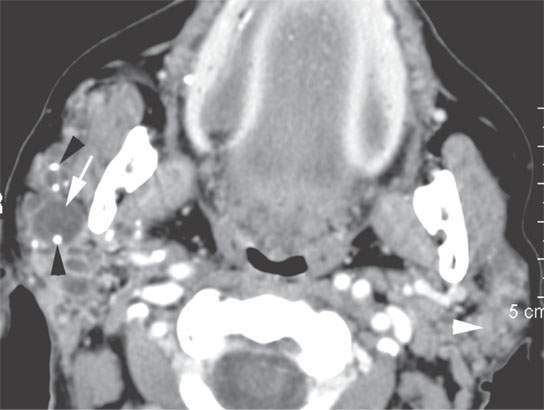

FIGURE 20.3. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography shows enhancing nodularity in the left parotid gland (white arrowhead) in this patient with Sjögren syndrome. The pattern is nonspecific and can be seen in sarcoidosis and chronic recurrent infectious parotitis. This degree of nodularity usually is not a normal variation. The right parotid shows more florid changes of chronic punctate sialoadenitis manifest by parenchymal nodularity, cysts (white arrow in A) and sialolithiasis (black arrowheads), in this case due to autoimmune disease. Such changes also can be seen in chronic infectious sialoadenitis.

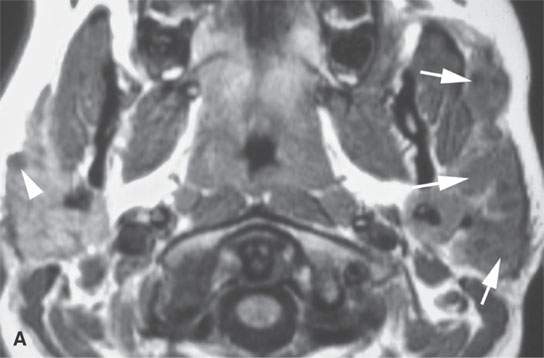

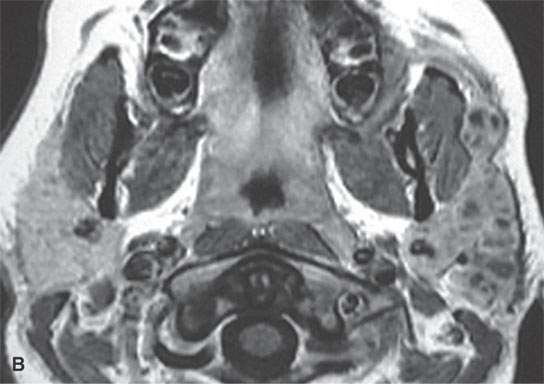

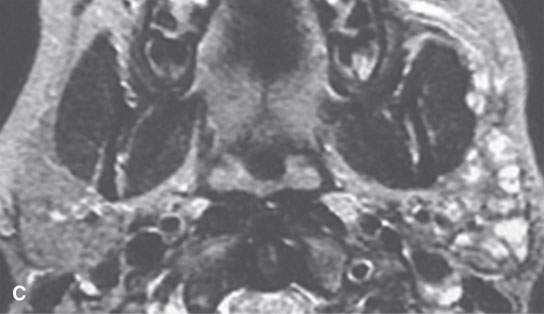

FIGURE 20.4. Magnetic resonance imaging shows enhancing nodularity (compare the non–contrast-enhanced T1-weighted image in A with the contrast-enhanced T1-weighted image in B) and cysts throughout the left parotid gland (arrows) in this patient with Sjögren syndrome. A few cysts were present on the right (white arrowhead in A). The pattern is nonspecific and can be seen in chronic recurrent infectious parotitis. The T2-weighted image in (C) confirms the nature of the cysts.

FIGURE 20.5. Non–contrast-enhanced computed tomography of a patient with “burned-out” Sjögren disease of the lacrimal glands. Both glands are atrophic(arrowheads), and the right shows dystrophic calcification (arrows).

FIGURE 20.6. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of a patient with “burned-out” Sjögren syndrome shows nonenhancing nodularity in the parotid gland mixed with fatty atrophic changes and sialoliths (A). In (B), the sublingual glands are shown to be atrophic (arrows). In (C), the submandibular glands (arrows) are atrophic.

Sjögren syndrome is a predisposing factor for lymphoma that perhaps is potentiated by some of the medications used to treat the chronic inflammatory disease; once glandular changes become solid or larger aggregate masses or nodes become progressively larger (Figs. 20.7–20.9), this complication must be considered likely. Adjunctive imaging findings may be sought to confirm the suspicion (Fig. 20.8), and biopsy of the gland or nodes should be strongly advised.

FIGURE 20.7. Baseline parotid and nodal disease in a patient with chronic active Sjögren syndrome shown (A, B). Parotid tail nodes (arrowheads) were enlarged on the left, and there was a solid parotid tail mass on the right (arrow). The patient subsequently developed infiltrating parotid masses, (C) and the nodes more than doubled in size (arrowheads in D). Lymphoma was suspected based on the imaging and was confirmed by biopsy.

FIGURE 20.8. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography in another patient with chronic active Sjögren syndrome manifest in the parotid glands (arrows) who had an infiltrating nasopharyngeal mass as evidence of lymphoma noted on a scan done to evaluate a possible parotid mass (arrowheads). Lymphoma was confirmed.

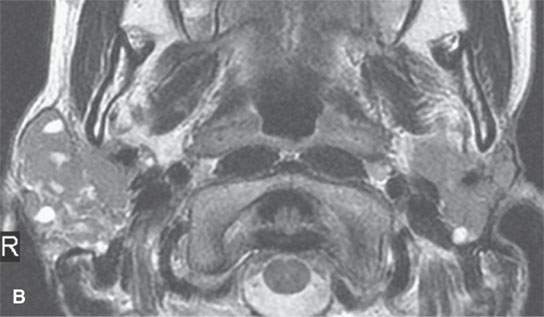

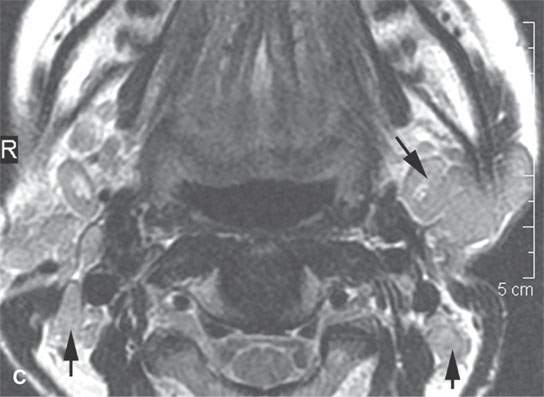

FIGURE 20.9. Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance in a patient with chronic active Sjögren syndrome. The patient subsequently developed infiltrating, enhancing (A) parotid masses, and the level 2 nodes were enlarged (arrows in C). T2-weighted image in (B) shows a signal intensity fairly typical of lymphoma, although it is not that specific in itself. Lymphoma was suspected based on the imaging and was confirmed by biopsy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree