INFECTIOUS AND NONINFECTIOUS INFLAMMATORY DISORDERS: VASCULITIS INCLUDING ARTERITIS, THROMBOPHLEBITIS, AND VASCULAR THROMBOSIS

KEY POINTS

- Venous and arterial disease is an important conduit of inflammatory disease spread in the head and neck.

- Venous and arterial structures are frequently secondarily involved in head and neck pathology, and their involvement may be the most crucial feature of the disease.

- Some of the most disastrous functional outcomes can be the result of vascular complications, especially with regard to the eye and brain.

- Computed tomographic angiography, and to a lesser extent magnetic resonance imaging, magnetic resonance angiography, diffusion-weighted imaging, and susceptibility-weighted imaging, have replaced catheter angiography for initial screening for possible vascular abnormalities related to inflammation.

- While an excellent tool for vascular pathology, ultrasound has only a very limited role to play in these diseases, as it does not show the full extent and nature of disease and/or related findings.

VENOUS INFLAMMATION, INFECTIONS, AND OCCLUSION

Pathophysiology

Venous thrombosis or thrombophlebitis may complicate or be the source of an inflammatory process in the head and neck region.1 In general, the involved vessel or sinus contains clot and varying degrees of perivascular inflammation induced by causative pathology that somehow irritates the endothelium and starts the clotting cascade.

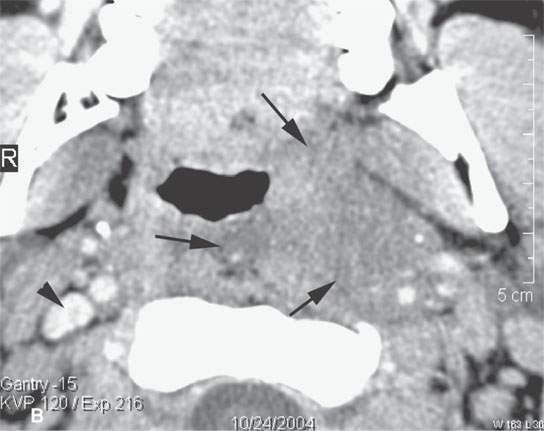

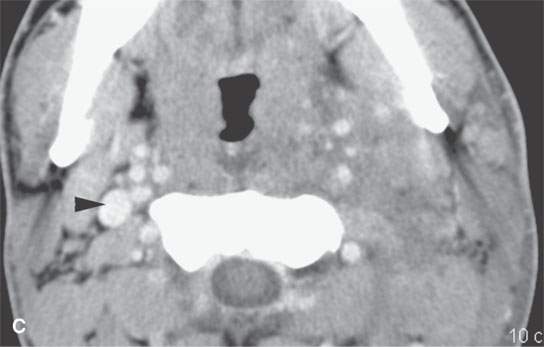

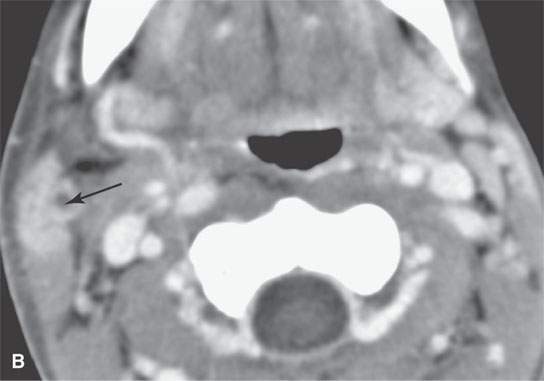

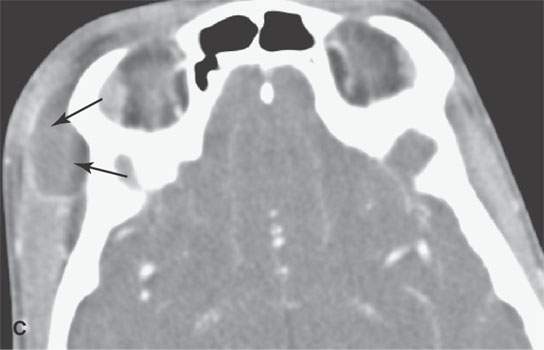

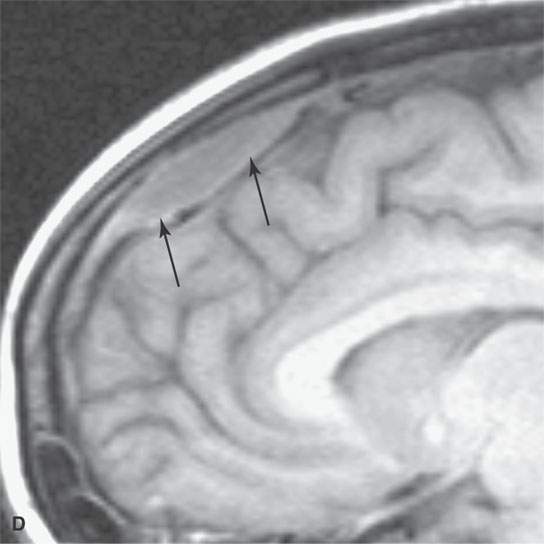

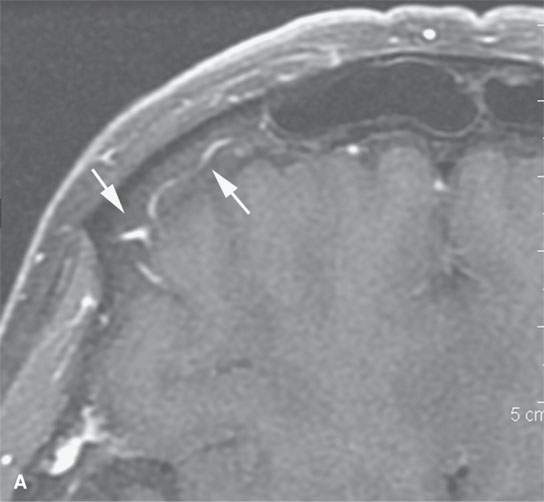

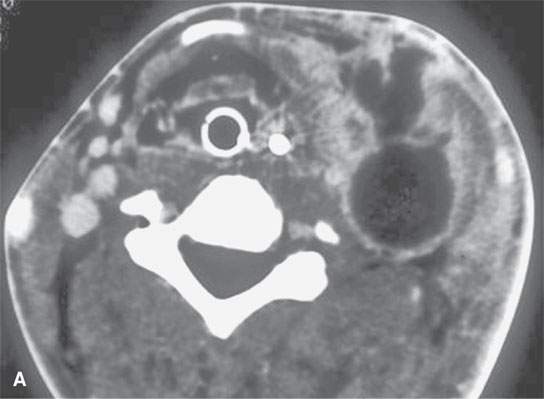

Causative pathology initiating venous disease is most frequently in the sinuses and mastoid. Two common examples are sigmoid sinus thrombosis secondary to mastoiditis and jugular vein thrombophlebitis related to indwelling catheters. Other sources include the pharynx, such as Lemierre tonsillogenic venous thrombosis (Fig. 15.1), sinus infections, and occasionally the skin (Fig. 15.2).

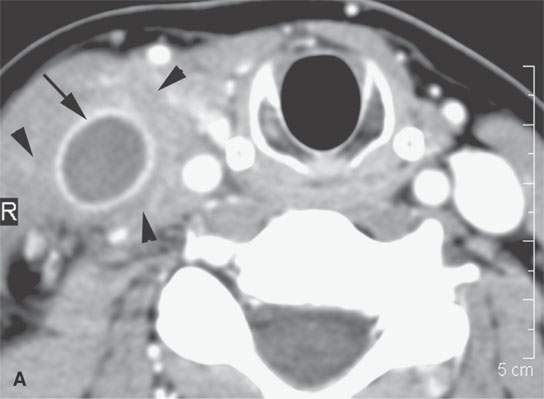

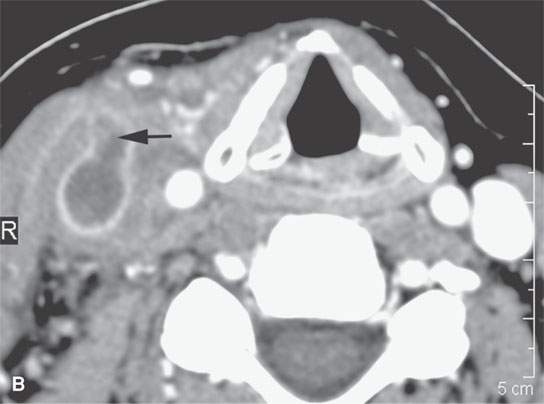

FIGURE 15.1. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography in a patient with severe bacterial tonsillitis studied to exclude an abscess. The image in (A) shows a suppurative retropharyngeal lymph node (arrow) and extensive cellulitis. The jugular vein is occluded (arrowhead). In (B) and (C), the cellulitis is shown to be very extensive, and the jugular vein is occluded compared to the patent normal right vein.

FIGURE 15.2. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography and magnetic resonance (MR) imaging of a patient with a skin infection that traveled via the external jugular vein (arrows in A and B) to create an extracranial abscess in the deep scalp (arrows in C) and via transdiploic vessels to create an epidural abscess as seen (arrows) on the sagittal MR image in (D).

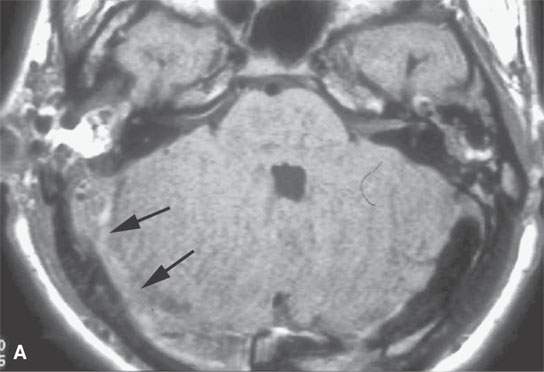

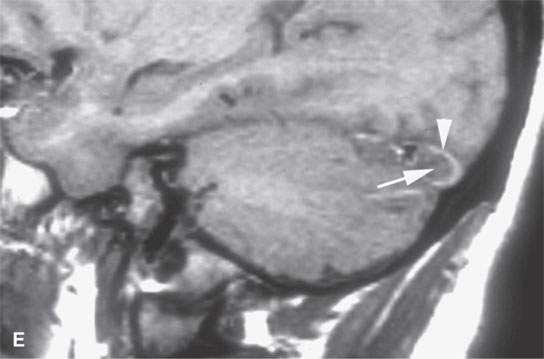

Septic thrombophlebitis is an important route of spread of infectious disease from the extracranial head and neck structures to the intracranial compartment.2,3 Such spread may be via transdiploic vessels to the skull, epidural space, subdural space, subarachnoid space, and brain (Fig. 15.3). Either bland or septic involvement of the cavernous sinus, other major dural sinuses, and cortical veins is possible. Any or all of these vascular structures may be simultaneously involved (Fig. 15.4). Intracranial involvement due to such vascular spread is often close to the inciting infection but can be fairly remote (Fig. 15.2).4

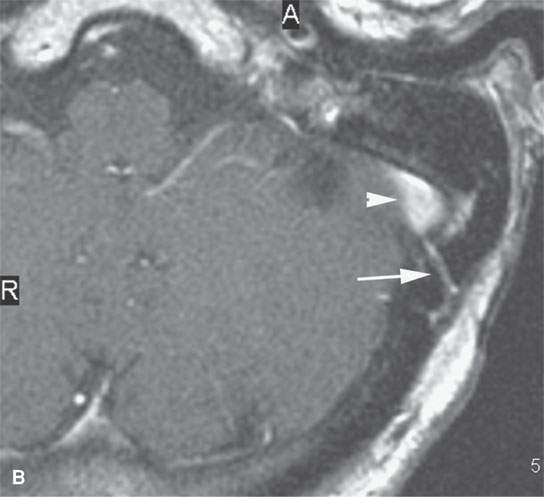

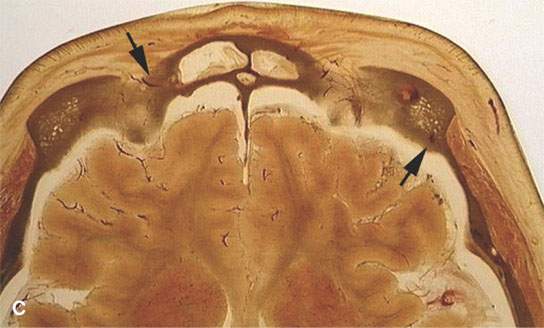

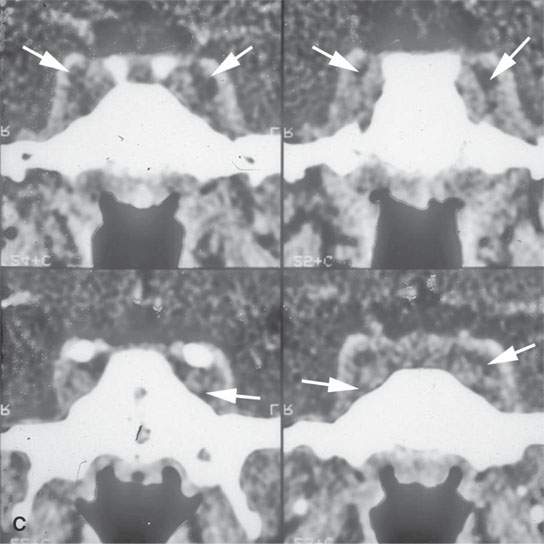

FIGURE 15.3. Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance images showing frontal (arrows in A) transdiploic vessels that are a potential route of spread of sinus disease intracranially and in (B) a transdiploic vein (arrow) in the temporal bone communicating with the sigmoid sinus (arrowhead). The latter pathway could account for an epidural abscess or a thrombosed sigmoid sinus due to mastoid infection. (C) Anatomic section showing transdiploic vessels (arrows).

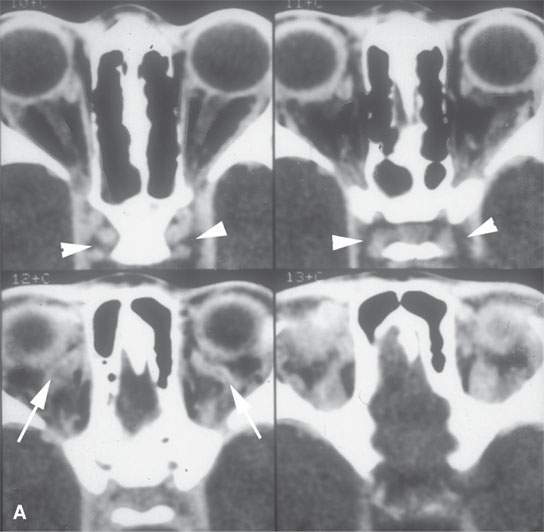

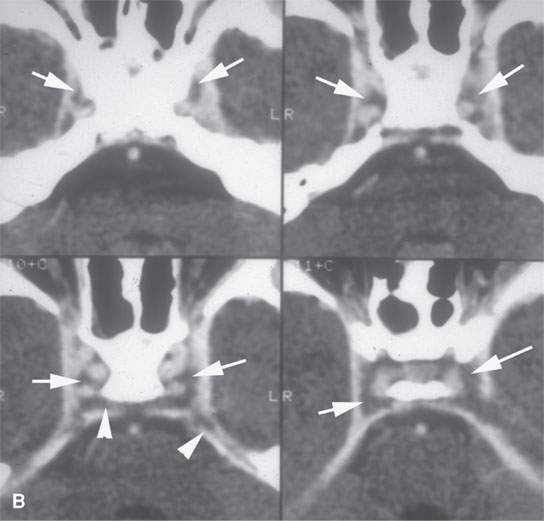

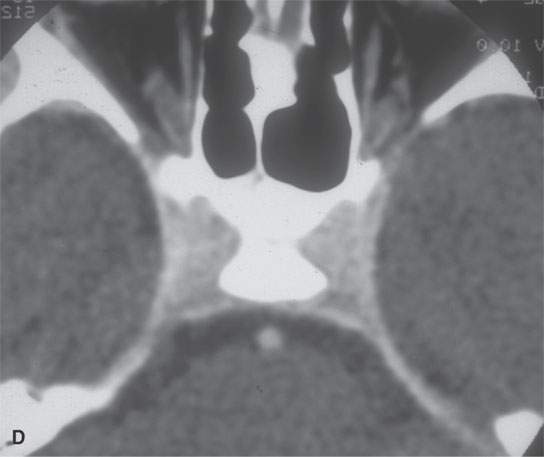

FIGURE 15.4. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of a patient with bilateral cavernous sinus thrombosis. A: The secondarily occluded ophthalmic veins are dilated (arrows), and the venous sinusoids of the cavernous sinus do not fill (arrowheads). B: The sinusoids do not fill (arrows), and clot extends into the clival plexus and superior petrosal sinuses (arrowheads). C: The coronal series confirms the lack of sinusoid filling, even on these images that were delayed. D: The follow-up study shows all findings to be resolved.

The rate of clot lysis and restoration of flow depends on the causative condition and the treatment of the original inciting condition.

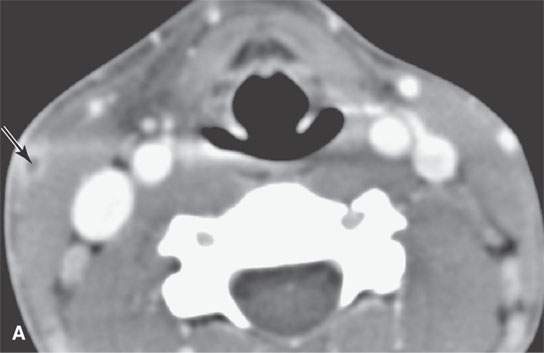

Imaging Manifestations

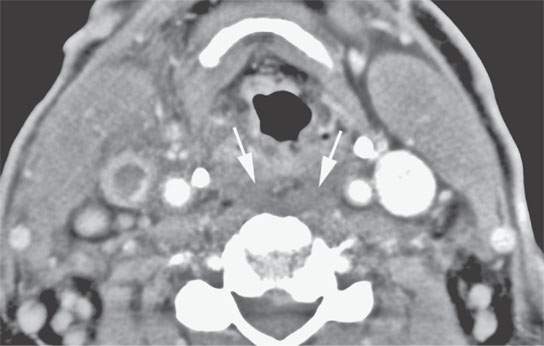

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) will show the clotted vessel or sinus to be obviously occluded compared to normally patent enhancing vessels with flowing blood (Figs. 15.1, 1.15, and 2.15).3,5,6 Typically, the occluded vessel or venous sinus lumen appears to be homogeneously fluid density, and its wall often enhances (Fig. 15.5). There may be varying degrees of surrounding edema/inflammation. Rarely, morphology similar to that of an abscess will be present and strongly suggest suppurative thrombophlebitis (Fig. 15.6). In the neck, retropharyngeal and peripharyngeal edema is frequently present (Fig. 15.7).

FIGURE 15.5. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of internal jugular vein thrombophlebitis, with the thrombosed lumen seen in both (A) and (B) and clot propagating into a branch vessel (arrow) in (B). Surrounding soft tissue swelling (arrowheads) and vessel wall enhancement (arrow) in (A).

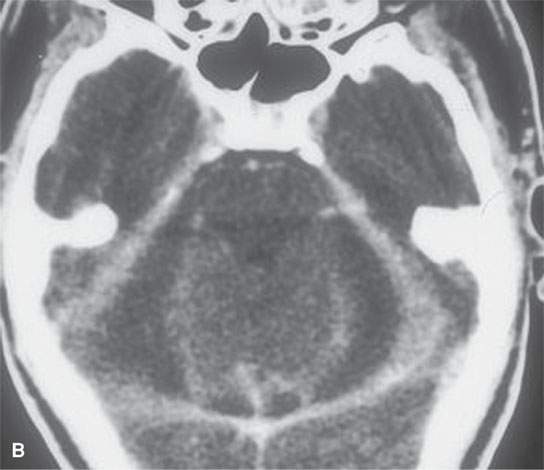

FIGURE 15.6. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of a patient with advanced septic thrombophlebitis that eventually formed a deep neck abscess as seen in (A) as a complication of a mastoid infection. The secondary subdural posterior fossa empyemas are shown in (B).

FIGURE 15.7. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of a patient with jugular thrombophlebitis. The retropharyngeal edema (arrows) present occurs very frequently in this condition and should not be mistaken for an inciting retropharyngeal abscess. It is simply reactive edema or on occasion cellulitis.

On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the normal flow void as seen on spin echo (SE) images or loss of flow-related enhancement as seen on gradient echo (GE) images will be absent, and the vessel lumen will be filled with material that is of variable intensity on T1-weighted (T1W) images and T2-weighted (T2W) images depending on the age of the clot (Fig. 15.8).6,7 Flow-related enhancement may be mistaken for clot, and a combination of flow-sensitive GE and standard T1W and T2W images in at least two different planes may be necessary to differentiate flow-related artifact from clot. Magnetic resonance (MR) venography is an excellent adjunctive method to confirm the diagnosis that is usually strongly suspected on the anatomic, non–flow-related images. Susceptibility-weighted techniques can be used to improve on time-of-flight MR venography and produce extraordinary images of the manifestations of relatively small vessel venous disease in the brain. Diffusion-weighted images are used in conjunction with the anatomic and flow-related imaging to determine the effects of vascular occlusion on the brain and may help determine whether intervention is likely to improve the situation (Fig. 15.9)

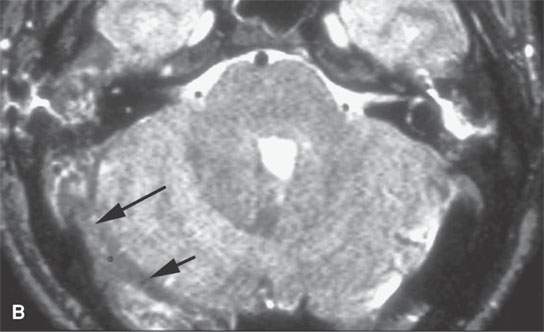

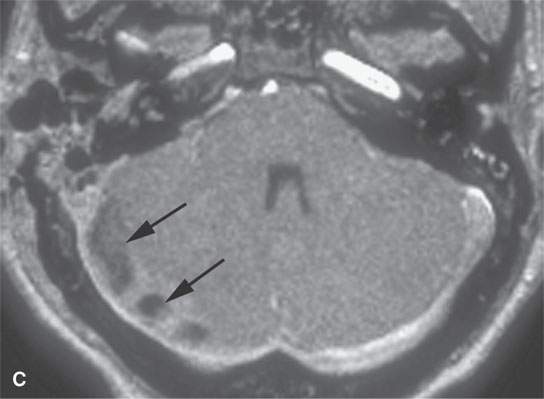

FIGURE 15.8. Magnetic resonance (MR) images of a patient with mastoiditis and secondary sigmoid and transverse sinus thrombosis. T1-weighted (A), T2-weighted (B), gradient echo (C), and MR venography (D) all show the variable appearance of the clotted sinus on these pulse sequences (arrows). In (E), the clotted sinus is seen in cross section on a non–contrast-enhanced T1-weighted image with the periphery of the clot (arrowhead) higher in signal intensity than the more central portion (arrow).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree