Fig. 20.1

Categorization of SARS coronavirus

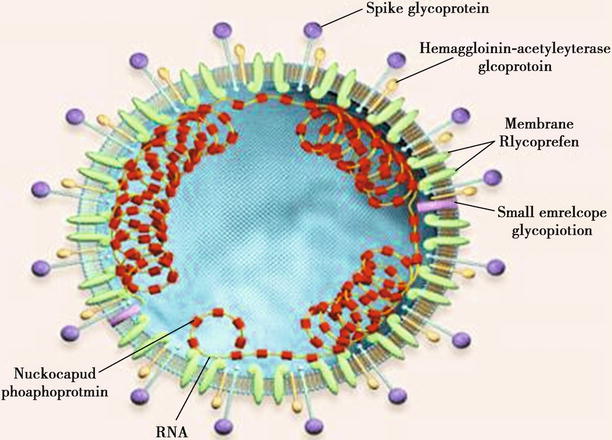

Fig. 20.2

Structural pattern of coronavirus particle

The resistance and stability of SARS-CoV in the external environment are stronger than other human coronaviruses. It can survive for 4 days on the dry plastic surface, at least 1 day in urine, over 4 days in stool of patients with diarrhea, and 15 days in the blood. On the surfaces of plastic, glass, mosaic, metal, cloth, and photocopy paper, it can survive for 2–3 days. SARS-CoV is sensitive to temperature, with weaker resistance at higher temperature. It can be inactivated at a temperature of 56 °C for 90 min and 75 °C for 30 min. SARS-CoV can be killed by diethyl ether at 4 °C for 24 h. And it can be inactivated by 75 % ethanol for 5 min or by disinfectants containing chlorine for 5 min. In addition, the virus is sensitive to ultraviolet radiation.

20.2 Epidemiology

20.2.1 Source of Infection

The patients are the major source of infection. At the acute stage, the patients carry a large quantity of viruses with serious respiratory symptoms, and the viruses are likely to be excreted from the respiratory tract. The patients with respiratory failure, especially those receiving tracheal cannulation or mechanical ventilation, have more secretions at the respiratory tract, with strong infectivity. The patients at the incubation period show low or no infectivity. The patients at the convalescent stage have not been reported to infect others. Epidemiological data have demonstrated that SARS-CoV mainly induces asymptomatic infection. Subclinical infection has not been sufficiently proved, and chronic patients carrying the virus have not been found.

Studies have demonstrated that the gene sequence of coronavirus isolated from civet cats and other animals is highly homologous with SARS-CoV, indicating that these animals may be the reservoir hosts of SARS-CoV and source of its infection. Therefore, SARS is likely to be an animal-borne infectious disease.

20.2.2 Route of Transmission

Spread by air droplets within a short distance is the major route of its transmission. In the throat swab and sputum specimen from patients at the acute stage, SARS-CoV can be detected. Spread along with aerosol is another route of its transmission. The susceptible individuals can be infected after inhalation of SARS-CoV containing aerosol suspended in the air. Spread via touches is also an important route of its transmission. For instance, the hands of susceptible individuals directly or indirectly touch secretions and excreta from the patients or utensils contaminated by the virus. Then the virus infects the human body via the mouth, nose, and ocular mucosa. Moreover, it can also be transmitted via virus-containing aerosol in the laboratory with inappropriately preserved SARS-CoV strains. In April 2004, a typical accident was reported that inappropriately preserved SARS-CoV strains in a laboratory in Beijing, China, caused five cases of infection with one case of death. During the epidemic period, nosocomial infection is more likely to occur. The main routes include: (1) Medical staff is infected by direct contact to the patients during treatment and attendance. The direct contacts are more likely to occur during oral cavity examination and tracheal cannulation with the medical staff inappropriately protected. (2) The visitors and those responsible for attending the patients are likely to be infected. (3) The patients with other diseases can be infected due to sharing the ward with a patient with SARS. Nosocomial infection is closely related to facilities of the ward, severity of the symptoms, stage the conditions are in, immunity of individuals with contact history, and personal protective measure of medical staff and visitor.

20.2.3 Susceptible Population

People are generally susceptible to SARS, with higher incidence in young adults and teenagers. But children and the elderly are also vulnerable to infection. The high-risk groups include family members of the patients, medical staff, nursing workers, and visitors. Based on data from You’an Hospital, Beijing, in 108 cases with clinically defined diagnosis of SARS, 31 cases are medical staff, accounting for 28.7 %; 32 cases are family members, 29.6 %. Cases of SARS complicated by diabetes, heart diseases, or other chronic diseases have higher mortality rate. After infection, the individuals can acquire certain immunity but its duration still needs further studies.

20.2.4 Epidemiological Features

20.2.4.1 Prevailing Seasons

SARS is a serious infectious disease with its earliest occurrence in the twenty-first century. It prevails in winters and springs, with occurrence of obvious familial and hospital agglomeration. Its occurrence in the community is mainly sporadic, with occasional occurrence of spot outbreak.

20.2.4.2 Chronological Distribution

In Nov. 2002, occurrence of SARS within members of one family was firstly reported in Foshan, Guangdong, China. In the following months, its occurrence rapidly spreads to more than 30 countries and regions including Guangzhou, Beijing, Hong Kong, Vietnam, and California. According to a report by the WHO, by June 20, 2003, prevalence of SARS had involved 28 countries and 32 regions across the world. A total of 8,461 cases had been reported, with 7,218 cases discharged from the hospital after treatment and 916 cases of death. The world average mortality rate of SARS is 9.5 %. In China, a total of 5,327 cases had been reported, with 4,959 cases cured and 349 cases of death.

20.2.4.3 Regional Distribution

Southeast Asia is the main affected area, especially mainland China, Hong Kong of China, Taiwan of China, Singapore, and Hanoi of Vietnam, followed by Thailand and the Philippines. Concerning Europe and America, the seriously affected area is Toronto in Canada, followed by the United States of America.

20.2.4.4 Age Distribution

Any age group may be affected, but mainly young and middle-aged adults (patients aged 20–49 years account for about 80 %). Its incidence rate has no gender difference. In cases of death, the elderly accounted for a larger proportion (about 40 % above the age of 60 years). And the mortality rate is higher in patients with SARS complicated by diabetes, heart diseases, or other chronic diseases.

20.3 Pathogenesis and Pathological Change

SARS-CoV is pantropic to human tissues, but its pathogenesis still remains elusive. It gains its access into the human body via the respiratory tract and replicates at the epithelium of respiratory mucosa. Then they are released into blood flow to cause viremia, with following invasion into various organs and tissues. And the virus mainly invades the lungs and immune system, with type I alveolar epithelial cells and lymphocytes possibly as its target cells.

By immunological assays, the specific antibody against SARS-CoV is detected in the serum, while SARS-CoV expresses M protein, N protein, S protein, and E protein to play its important pathogenic role. Clinically, SARS is characterized by acute lung inflammation and acute lung injury, with 5–10 % of cases complicated by ARDS and MODS. And the conditions of 90 % of such patients are self-limited. Lung inflammation caused by T lymphocytes is clinically parallel to its prognosis. By autopsy, pulmonary interstitial exudation, transudative inflammation, and alveolar injury are found. The germinal center of a lymph node is absent, and the count of lymphocytes decreases. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) involves the alveolar epithelial cells and pulmonary vascular endothelial cells to cause inflammatory congestion, further inducing large quantities of exudates of serous fluid and fibrinogen. The exudated fibrinogen agglutinates into cellulose, together with necrotic alveolar epithelial debris, to form hyaline membrane. The activated macrophages and lymphocytes can release cytokines and free radicals, which further increase the permeability of alveolar capillaries and induce the proliferation of fibroblasts. During the interaction of viruses with immune cells that infiltrate into the lung tissues, the host immune cells (including macrophages, neutrophils, etc.) overproduce free radical molecules, such as oxygen radicals (O− 2), nitric oxide radicals (NO), and its derivatives (ROS). Thus the infected cells and tissues are damaged.

The prominent pathological changes in cases of SARS occur at the lungs. Early pathological changes are characterized by pulmonary edema and formation of hyaline membrane. The advanced pathological changes include alveolar injuries, cellular and fibrous exudates, and interstitial infiltration of inflammatory cells with insufficient lymphocytes. By microscopic observation, the lungs are subject to diffuse exudative and acute hemorrhagic inflammation. There are also diffuse lesions of alveolar epithelial cells, highly dilated and congested alveolar capillaries, and apparent proliferation of alveolar wall due to edema and infiltration of lymphocytes and monocytes. Within most alveolar cavities, cellulose, erythrocytes, macrophages, and epithelial cells are observed, sometimes with formation of hyaline membrane. At the advanced stage, interstitial fibrosis and occlusion of alveolar fiber can be observed, with absent germinal center of a lymph node and decreased lymphocytes. Other organs, including the heart, liver, spleen, kidney, pancreas, and adrenal gland, are subject to different degrees of cellular hydropic degeneration, fatty degeneration, proliferation of interstitial cells, and other nonspecific pathological changes.

By autopsy of the death cases from SARS, it is demonstrated that SARS mainly involves the lungs and immune organs, such as the spleen and lymph node. Other organs, such as the heart, liver, kidney, adrenal glands, and brain, may also be involved with different degrees of lesions.

20.3.1 Lung

Generally, the lung in patients with SARS is apparently swollen, with increased weight. Except for cases with secondary infection, the pleura is quite smooth with a dark reddish or grayish brown color and with/without small quantity pleural effusion. On a section of lung tissue, homogeneous consolidation is commonly observed in a reddish brown or dark purplish color, which may involve any lung lobe resembling the hepatization stage of lobar pneumonia. In cases with secondary infection, abscesses in different sizes may be observed. The pulmonary vascular vessels are subject to thrombus and sometimes local pulmonary infarction (Fig. 20.3). In some cases, hilar lymphadenectasis can also be observed.

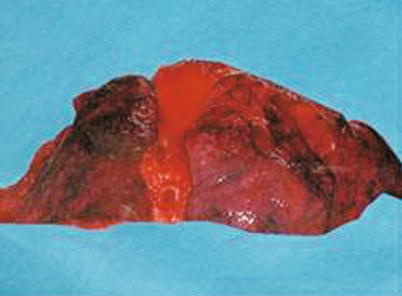

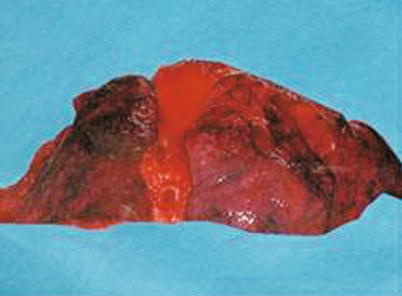

Fig. 20.3

Lung of SARS. By naked eyes observation, the lung is swollen with a dark reddish color and with hemorrhage lesions

Under a light microscope, the pathological changes at the lungs are usually diffuse and almost involve all lung lobes. The changes are characterized by diffuse alveolar injury, with manifestations at different stages. At around day 10 of the illness course, the pathological changes include pulmonary edema, cellulose exudation, formation of hyaline membrane, desquamative pneumonia induced by accumulation of macrophages and shedding of type II alveolar epithelial cells in alveolar cavity, and focal pulmonary hemorrhage. These pathological changes can be observed on autopsy specimen and biopsy specimen collected by bronchofiberscopy. Some proliferated alveolar epithelium fuses into each other to form zygote-like multinucleated giant cells. In the proliferated alveolar epithelium and the cytoplasm of exudated monocyte, viral inclusion bodies can be observed (Fig. 20.4). Along with progress of the condition, in cases with an illness course exceeding 3 weeks, organization of intra-alveolar exudates and hyaline membrane as well as hyperplasia of fibroblasts in alveolar septum can be observed. Both of them constantly integrate to cause alveolar occlusion and atrophy, with consequent lung consolidation. Only in some cases, apparent fiber hyperplasia occurs to induce pulmonary fibrosis or even sclerosis. In intrapulmonary small blood vessels, fibroid microthrombus can often be found. For the above pathological changes, great individual difference can be found. Even in the lungs of one patient, pathological changes of different stages can be found. In some cases, especially those who have received long-term treatment, sporadic lobular pneumonia or even large-area fungal infection can be commonly found, and the most commonly found fungal infection is aspergillus infection. The secondary infections can involve the pleura to cause pleural effusion, pleural adhesion, or even occlusion of pleural cavity.

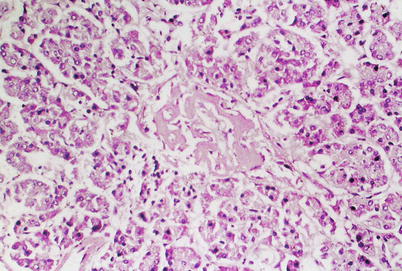

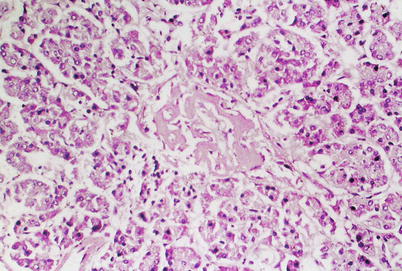

Fig. 20.4

Pulmonary pathological changes of SARS. (a) Evenly light-stained acidophilic exudates at the margin of alveolar cavity and formation of hyaline membrane (H&E, ×200). (b) Degeneration and necrosis of epithelial cells at the alveolar wall; shedding type II alveolar epithelial cells in the alveolar cavity; infiltration of small quantity lymphocytes and monocytes in alveolar septum (H&E, ×200). (c) Multinucleated giant cells in the alveolar cavity (H&E, ×400). (d) Obvious widening and edema of alveolar septum; dilation and congestion of interstitial blood vessels (H&E, ×400). (e) Hyperplasia of collagen fibers in alveolar septum, with a rose-red color and irregular shape (PTAH, ×200). (f) Hyperplasia of reticular fiber at alveolar capillary wall and the consequent irregular thickening of the capillary wall (reticular fiber, ×200). (g) Eosinophilic structure similar to virus inclusion body in alveolar epithelial cells, spherical in shape and surrounded with transparent halo sign (H&E, ×400). (h) Positively expressed N protein of SARS-CoV in cytoplasm of type II alveolar epithelial cells in the alveolar cavity, with red staining by AEC (immunohistochemistry, ×200). (i) Strong expression of NF-KB in cytoplasm of shed alveolar epithelial cells (immunohistochemistry, ×200). (j) In situ PCR demonstrates alveolar tissue with expressed nucleic acid of SARS-CoV in cytoplasm of alveolar epithelial cells, in blue-violet color (in situ PCR, ×400). (k) Positive expression of some c-kit in proliferated alveolar epithelial cells, with red staining by AEC (arrow) (immunohistochemistry, ×200). (l) Strong expression of TGF-β, in brownish-yellow color (immunohistochemistry, ×200). (m) Immunohistochemistry double-label staining demonstrates double positive, CD68 (blue) and NF-KB (red), of the shed cells in the alveolar cavity (immunohistochemistry, ×200). (n) Congestion and necrosis of hilar lymph nodes, decreased quantity of proper lymphocytes, and atrophy and absence of lymphatic nodules (H&E, ×400)

By electron microscopy, the alveolar epithelium is swollen, with apparent vacuolar degeneration of the mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum. The alveolar epithelial cells are subject to proliferation, especially type II epithelial cells. For proliferated type II epithelial cells, the laminated body in the cytoplasm is decreased, with massive proliferation and expansion of both rough and smooth endoplasmic reticula. In the expanded endoplasmic reticulum cistern, protein secretions with increased electronic density are observed. In some expanded endoplasmic reticulum, clustering virus particles in uniform size can be observed, with tiny corolla-shaped particles at their surface whose size is 60–120 nm. The interstitial vascular endothelial cells are subject to swelling and vacuolar degeneration.

20.3.2 Immune Organs

20.3.2.1 Spleen

In some patients with SARS, the spleen is subject to swelling but some shrinkage. On the spleen section of some cases, spleen mud can be observed. By microscopy, the spleen is subject to poorly defined splenic corpuscle, atrophy of white pulp, sparse lymphocytes with decreased quantity, congestion of red marrow, obvious bleeding and necrosis (Fig. 20.5), and increased histiocytes.

Fig. 20.5

Splenic pathological changes of SARS. (a) Focal hemorrhage and necrosis in the spleen and atrophy of the white pulp (H&E, ×200). (b) S-100-positive lymphocytes in the spleen (immunohistochemistry, ×200)

20.3.2.2 Lymph Node (Abdominal Lymph Nodes and Hilar Lymph Nodes)

In some cases, swelling of the lymph nodes can be observed. Microscopy has demonstrated that almost all lymph nodes are subject to atrophy and absence of lymph follicles but with different degrees. The lymphocytes are sparsely distributed, with decreased quantity. The vascular vessels and lymph sinus are subject to obvious dilation and congestion, with obvious proliferation of sinus histiocytes and even bleeding and necrosis in some cases.

20.3.3 Pathological Changes of Other Organs

20.3.3.1 Liver

In most cases, the hepatocytes are subject to slight hydropic degeneration, focal fatty degeneration, and cord dissociation. In the liver lobule, the Kupffer cells are obviously increased, with infiltration of small quantity lymphocytes at the portal area (Fig. 20.6). In some cases, obvious hepatocytic necrosis can be found around the central vein.

Fig. 20.6

Hepatic pathological changes of SARS. (a) Swollen hepatocytes, proliferation of intralobular Kupffer cells, slightly enlarged portal area, and infiltration of small quantity monocytes (H&E, ×400). (b) Flakes and strips of necrosis of hepatocytes at lobular area III (H&E, ×400)

20.3.3.2 Heart

In patients with SARS, cardiac hypertrophy is common, generally characterized by uniform thickening of the left and right heart. Interstitial edema of the myocardium is obvious, with interstitial infiltration of sporadic lymphocytes and monocytes. In some cases, the myocardial cells are subject to vacuolar degeneration, focal myocarditis, and small focal necrosis. Severe secondary infection, such as fungal infection, can also involve the heart (Fig. 20.7).

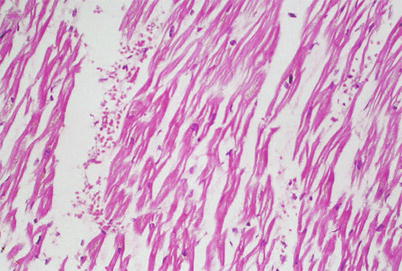

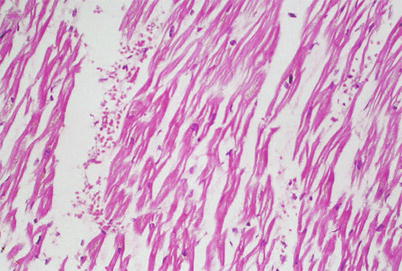

Fig. 20.7

Cardiac pathological changes of SARS. Atrophy of myocardial cells, congestion and edema between cells, and infiltration of small quantity monocytes (H&E, ×200)

20.3.3.3 Kidney

In most patients with SARS, obvious glomerular congestion and degeneration of epithelial cells at the renal tubules can be found. In some cases, extensive fibrinous thrombus in glomerular capillaries can be found. In some cases, there are intramedullary small focal necrosis and infiltration of lymphocytes and monocytes. Dilation and congestion of renal interstitial vascular vessels are also found. In some cases, small pyogenic lesions can be found due to secondary infection, with occasional occurrence of vasculitis.

20.3.3.4 Adrenal Glands

In some cases, focal hemorrhage can be found at the cortex and medulla, with necrosis, infiltration of lymphocytes, vacuolar degeneration of cortical fascicular cells, and/or decreased content of adipoid tissue.

20.3.3.5 Brain

The brain tissue is subject to varying degrees of edema and sometimes sporadic neuronal ischemic changes. In severe cases, the brain tissue is even subject to necrosis. Some nerve fibers are subject to demyelization.

20.3.3.6 Bone Marrow

In most patients, the counts of neutrophils and the megakaryocytic system in hemopoietic tissue are subject to relative decrease. In some cases, erythroid cells are characterized by small focalized proliferation.

20.3.3.7 Gastrointestinal Tract

The submucosal lymphatic tissue is decreased at each segment of the stomach, small intestine, and colon, with sparse lymphocytes and interstitial edema. In some cases, superficial erosion or ulceration can be found at the stomach.

20.3.3.8 Pancreas

Interstitial vascular congestion is found. In some cases, slight interstitial fibrous proliferation and infiltration of lymphocytes can be found. There are also acinar atrophy at exocrine glands, decreased zymogen granules, and degeneration of some islet cells (Fig. 20.8).

Fig. 20.8

Pancreatic pathological changes of SARS. Atrophy of pancreatic acinus, infiltration of a small quantity of monocytes in interstitial tissue, and hyaline degeneration of islet (H&E, ×200)

The gallbladder is demonstrated with no obvious pathological changes.

20.3.3.9 Reproductive System

The testis is sometimes subject to degeneration of spermatogenic cells, with reduced spermatogenesis. Interstitial vascular dilation and hemorrhage can be observed.

The prostate, uterus, ovaries, and fallopian tubes are demonstrated with no obvious pathological changes.

In addition, polyangiitis based on venules can be found at the lungs, heart, liver, kidney, brain, adrenal glands, and striated muscle of some cases. Polyangiitis is characterized by edema of vascular wall and perivascular tissue, swelling and apoptosis of vascular endothelial cells, fibrinoid necrosis of vascular wall, and infiltration of monocytes and lymphocytes at vascular wall and perivascular tissue.

20.4 Clinical Symptoms and Signs

The incubation period lasts generally for 1–16 days, averagely 3–5 days. In extremely rare cases, it may last for as long as 20 days.

20.4.1 Main Symptoms

20.4.1.1 Fever

Fever is the initial symptom at onset, mostly high fever that is remittent or irregular and occasional accompanying chills.

20.4.1.2 Systemic Toxic Symptoms

The patients experience systemic toxic symptoms, such as headache, joint soreness, general soreness, fatigue, chest pain, and diarrhea.

20.4.1.3 Respiratory Symptoms

Cough possibly occurs that is mostly dry cough at the early stage, with rare sputum and chest distress. The patients experience no upper respiratory catarrhal symptoms. Along with progress of the conditions, the symptoms aggravate, with shortness of breath and frequent irritated cough with whitish thick or bloody sputum. In cases complicated by bacterial or fungal infection, sputum may be yellowish or foamy. In severe cases, the patients also experience asthmatic suffocation and dyspnea, which may further develop into acute respiratory distress syndrome.

20.4.1.4 Pulmonary Signs

The pulmonary signs are commonly not obvious. Some patients may show dry and/or moist rales at the lungs or lung consolidation sign. Occasionally, signs of small quantity pleural effusion may be found, with local dull sound by percussion and decreased breathing sound.

20.4.2 Clinical Staging

According to the clinical guideline for SARS stipulated by the Chinese Medical Association and Chinese Traditional Medicine Society on Sept. 30, 2003, SARS is clinically staged into the early stage, the progressive stage, and the convalescent stage.

20.4.2.1 The Early Stage

Generally, the early stage refers to the initial 1–7 days after the onset. The disease had an acute onset with fever as its initial symptom. The body temperature is commonly above 38 °C, and more than half of patients experience headache, joint and muscle soreness, fatigue, and other symptoms. Some patients may also experience dry cough, chest pain, and diarrhea but rarely experience upper respiratory catarrhal symptoms, mostly with no obvious lung signs. In some patients, rare moist rales can be heard at the lungs. X-rays demonstrate the appearance of lung shadows at day 2 after the onset, averagely 4 days. Over 95 % of the patients are demonstrated with positive lesions at day 7 after the onset.

20.4.2.2 The Progressive Stage

The progressive stage refers to days 8–14 after the onset, but even longer for individual cases. During this stage, fever and toxic symptoms persist, with progress of lung lesions. Clinically, it is characterized by chest distress, shortness of breath, dyspnea, and tachycardia, which are especially obvious after physical activities. X-rays demonstrate rapid progress of lung shadows, which commonly involve multiple lung lobes. Rare patients (about 10–15 %) develop life-threatening ARDS.

20.4.2.3 The Convalescent Stage

After the progressive stage, the body temperature begins to decrease gradually, with alleviated clinical symptoms and absorbed lung lesions. Most patients are healed within about 2 weeks and can be discharged from the hospital. The absorption of lung lesions needs more time. In rare severe cases, restrictive ventilation disturbance and diffusion dysfunction of lungs may remain for a longer period of time, mostly returning to normal within 2–3 months after discharge.

20.5 SARS-Related Complications

Typical SARS undergoes three main stages: virus replication, abnormally active immune system, and organ damage. During the development of SARS and the therapeutic intervention, the possible complications are listed as the following:

20.5.1 Secondary Infection

Critical and severe cases of SARS sustain serious organ damages; in addition to compromised immunity, tracheal cannulation, and various invasive procedures, the patients commonly experience secondary bacterial and fungal infections. The elderly, patients with underlying chronic disease, patients with long-term management in the ICU, and those using immunosuppressive agents are especially vulnerable to these complications. Experts in Beijing have analyzed clinical data of 190 death cases from SARS, and they found that 46.3 % of cases underwent secondary infection of varying degrees, with 34 cases (36.8 %) of secondary bacterial infection, 32 cases (36.4 %) of secondary fungal infection, 2 cases of tuberculosis, and 20 cases (22.7 %) of secondary mixed infection. Accordingly, when rescuing patients with SARS, especially during use of large doses of hormones, the practitioners should be highly alert to the occurrence of secondary infections, with early precautions and active treatments.

20.5.2 ARDS and MODS

Most patients with SARS are basically healed after comprehensive treatment for 2–3 weeks. But some of the patients experience progressive aggravation of the conditions and develop acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Some patients even develop multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) and failure, with final occurrence of clinical death.

20.5.2.1 ARDS

The typical symptom of ARDS is respiratory distress, including varying degrees of cough, asthmatic suffocation, shortness of breath, and progressive dyspnea. The primary respiratory symptoms of SARS aggravate, and the patients develop typical bloody sputum at the advanced stage, with consciousness disturbances. By auscultation, bronchial breathing sounds, dry rales, crackles, or even bubbling sound can be heard at the lungs. Chest X-ray demonstrates infiltrative shadows at both lungs. The cases with a gas pressure at pulmonary capillary not higher than 18 mmHg or with clinically excluded cardiac pulmonary edema can be diagnosed as ARDS.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree