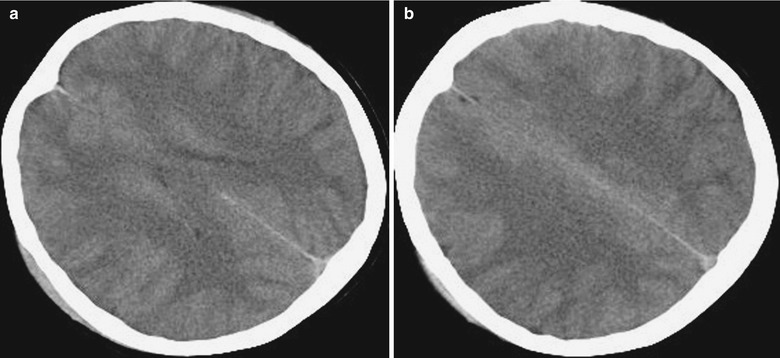

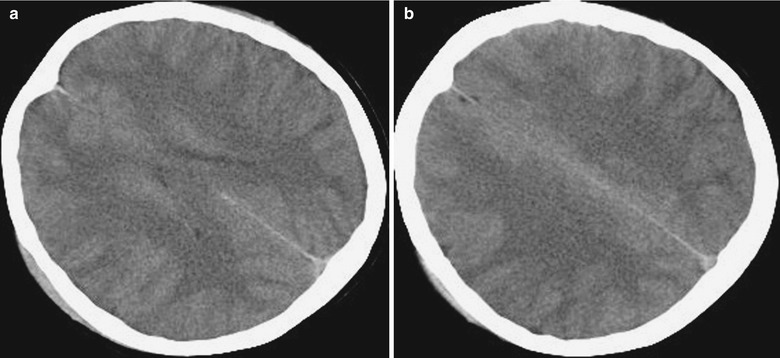

Fig. 22.1

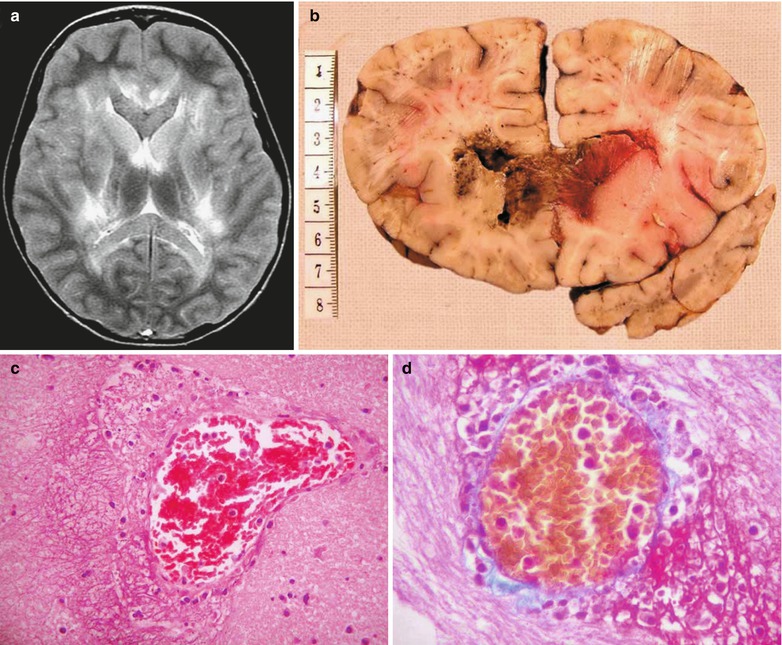

Influenza A (H1N1) complicated by encephalitis. (a, b) CT scanning demonstrated large flakes of low-density foci in the white matter surrounding bilateral cerebral ventricles and in the centrum ovale

Case Study 2

A female patient aged 20 years complained of fever and cough for 4 days as well as headache and conscious disturbance for 1 day. By physical examination, T 40 °C, bpm 128/min, R 25/min, BP 108/58 mmHg, and SPO2 95 %. She was in coma with no response to calling. Her respirations were sobbing-like, with positive cervical resistance and negative meningeal irritation sign. She also had congestive pharynx, occasional moist rales in both lungs, positive bilateral Babinski sign, and positive Chaddock sign. By laboratory tests, she was positive for viral nucleic acid of influenza A (H1N1). By routine blood tests, WBC 39.6 × 109 /L and GR% 92.4 %. By blood biochemistry, UA 676 μmol/L, CK 1482 U/L, CK-MB 347 U/L, and HBDH 1294 U/L. Death occurred due to shock complicated by DIC and multiple organ failure of the brain, lungs, heart, liver, and kidneys as well as critical influenza A (H1N1) complicated by virus meningoencephalitis.

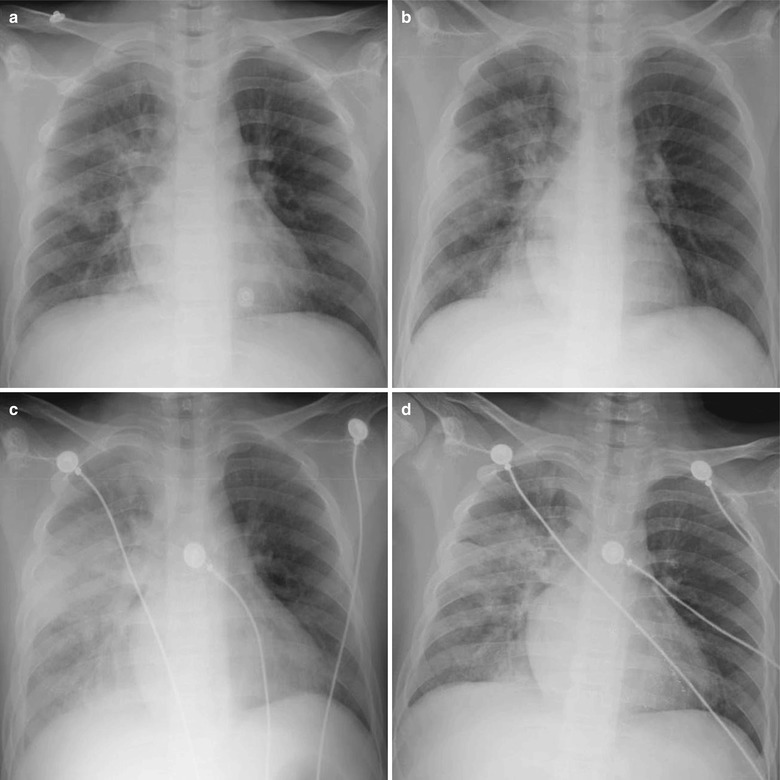

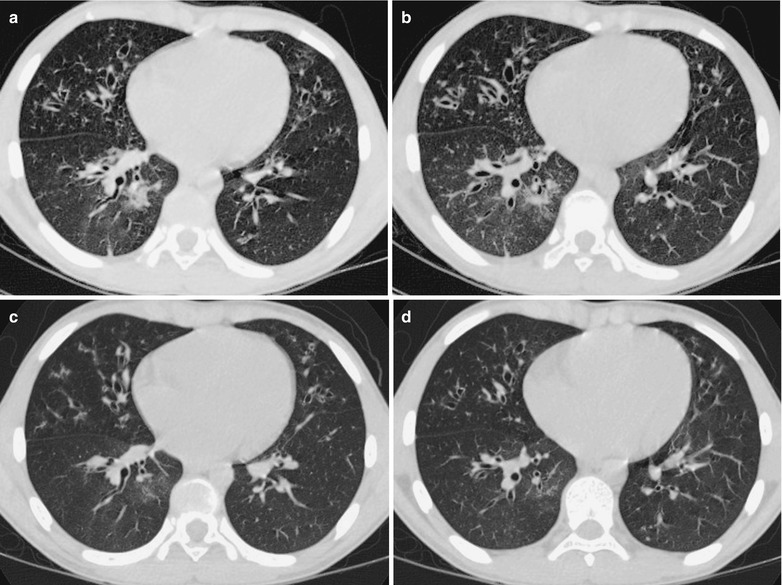

Fig. 22.2

Influenza A (H1N1) complicated by encephalitis. (a, b) CT scanning demonstrates large flakes of low-density foci in the white matter surrounding bilateral cerebral ventricles and in the centrum ovale

22.7.1.2 MR Imaging

MR imaging demonstrates diffuse demyelination in the cerebellar hemisphere, brainstem, and white matter of the cerebrum. Contrast imaging demonstrates patches of enhancement and gyrus enhancement in different sizes in the cerebellar hemisphere, brainstem, and parenchyma of the cerebral hemisphere. Haktanir reported one case of meningoencephalitis, with demonstrations of high signal by T2WI in the bilateral frontoparietal interfaces and thalamus. Contrast T1WI demonstrates obvious enhancement of the right frontoparietal interface and enhancement of meninges in bilateral cerebral hemispheres. Susceptibility weighted imaging of T2FFE demonstrates more obvious high signal in the right frontoparietal interface, with no cerebral edema.

Symmetric cerebral multiple foci are a characteristic manifestation of ANE, which can be well demonstrated by CT scanning and MR imaging. The foci are commonly found in the thalamus, tegmentum of the brainstem, white matter surrounding the lateral ventricles, and cerebellar medulla. CT scanning demonstrates symmetric low density in the bilateral thalamus, posterior limb of internal capsule, brainstem, and white matter of bilateral frontal, parietal, and occipital lobes. There are diffuse cerebral edema, absence of the sulcus and the fourth ventricle, and possible brainstem edema. Bilateral basal ganglia infarction has been also reported. MR imaging demonstrates symmetric long T1 and long T2 signals in the bilateral thalamus, basal ganglia, brainstem, splenium of the corpus callosum, bilateral centrum ovale, and paraventricular white matter, which are also high signals by FLAIR. Contrast imaging demonstrates linear and ring-shaped enhancement of the centrum ovale and thalamus but no abnormal enhancement of meninges. DWI demonstrates high signal in the bilateral thalamus or low central signal, boundary ring-shaped high signal, and high signal of other lesions. ADC image demonstrates slightly higher central signal surrounded by ring-shaped lower signal (low value of ADC). Cerebellar involvement is demonstrated as slightly long T1 and slightly long T2 signal in the bilateral cerebellar medulla and in the right cerebellar middle peduncle, which are in slightly high signal by FLAIR and high signal by DWI. Contrast imaging demonstrates obvious enhancement of cerebellar meninges. Compared to traditional sequences, DWI more favorably demonstrates pathological changes, with complex signal changes. DWI demonstrates low signal at the lesion centers in the bilateral thalamus whose pathological basis is necrosis of nerves and gliocytes and surrounding ring-shaped high signal whose pathological basis is cytotoxic edema and limited movement of water. ADC image demonstrates low signal in the center of the thalamus with surrounding high signal and elevated ACD value due to vasogenic edema (Figs. 22.3, 22.4, and 22.5).

Case Study 3

A girl aged 3 years complained of high fever and severe convulsion 2 days after catching a cold and diarrhea, with the highest body temperature reaching 41.2 °C. Her condition progressed into coma 2–3 days after her hospitalization. By laboratory test, severe liver failure was indicated, AST 16,852 U/L, ALT 10,300 mm3/L, LDH 27,878 U/L, and PLT 54,000/μL. By examination of cerebrospinal fluid, pressure 170 mmH2O and protein 232 mg/L. CT scanning demonstrates no abnormalities.

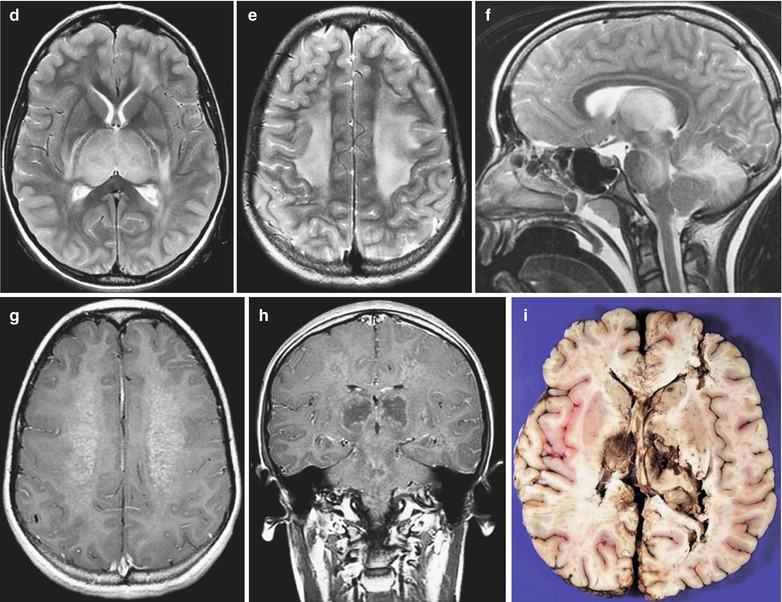

Fig. 22.3

Influenza A (H1N1) complicated by acute necrotizing encephalopathy. (a) In the acute stage, transverse T2WI demonstrates symmetrically increased signal in the bilateral thalamus and white matter surrounding the anterior and posterior horns of lateral ventricles. (b) Sagittal T2WI demonstrates high signals in the cerebellum and brainstem. (c) Sagittal T1WI demonstrates low signal in the brainstem and cerebellar hemisphere. (d) Transverse T2WI and GRE demonstrate low signal at the centers of foci in the thalamus, indicating hemorrhagic necrosis. (e, f) Transverse DWI and ADC image demonstrate limited diffusion of foci in the bilateral thalamus and white matter surrounding the anterior and posterior horns of lateral ventricles. (g) At day 10 after hospitalization, sagittal T1WI demonstrates high signals in the thalamus and cerebellum, in consistency with subacute hemorrhage. (h, i) In the chronic stage, at day 40 after hospitalization, MR imaging demonstrates severe sequelae. Transverse and sagittal T2WI demonstrate atrophy of the bilateral thalamus, with well-defined cavities inside the bilateral thalamus (Note: The case and images are from Ormitti F, et al. AJNR. 2010;31(3):396)

Case Study 4

A girl aged 12 years complained of cough and abdominal upset and, following persistent high fever, frequent diarrhea, asthenia, and general pain. She had no history of vaccination against seasonal influenza and influenza A (H1N1). Fast antigen detection by pharyngeal swab defined the diagnosis of influenza A (H1N1).

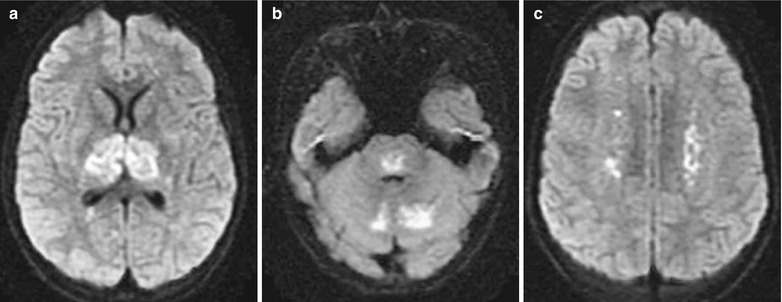

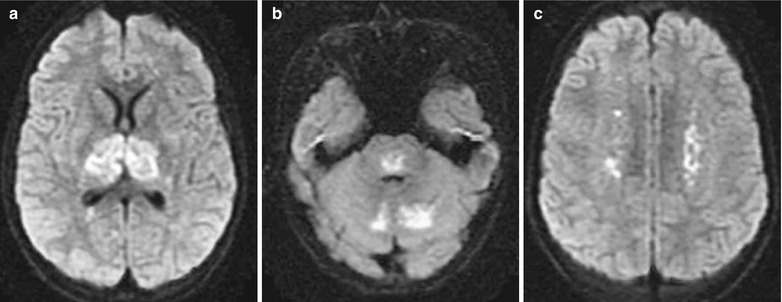

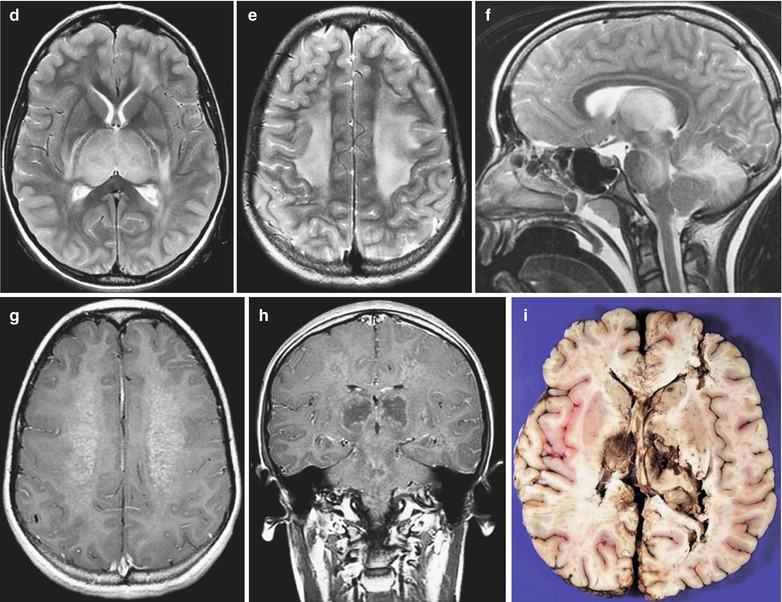

Fig. 22.4

Influenza A (H1N1) complicated by acute necrotizing encephalopathy. (a–c) Transverse DWI demonstrates limited diffusion of the bilateral thalamus, cerebellum, brainstem, and centrum ovale. (d, e) Transverse T2WI demonstrates slightly high or high signal in the thalamus and large flakes of high signals in the bilateral centrum ovale. (f) Sagittal T2WI demonstrates abnormal high signal in the thalamus, mesencephalon, pons, and cerebellum. (g) Contrast transverse T1WI demonstrates slight enhancement of the centrum ovale. (h) Contrast coronal T1WI demonstrates abnormal enhancement of the brainstem and centrum ovale as well as ring-shaped enhancement foci in the bilateral thalamus. (i) Autopsy demonstrates hemorrhagic necrosis of the bilateral thalamus (Note: The case and images are from Lyon JB, et al. Pediatr Radiol. 2010;40(2):200)

Case Study 5

A boy aged 7 years was hospitalized due to mental confusion and incoherent talking. He had experienced upper respiratory tract infection 2 weeks ago and had a past history of bronchial asthma. By laboratory test, ALT 5–25 IU/L and complete blood cell, blood sugar, and liver and lung function levels were normal. By cultures of nasopharyngeal secretion and throat swab, he was positive for influenza A (H1N1) virus antibodies. CT scanning fails to demonstrate any space-occupying lesions and cerebral edema. In 12 h after hospitalization, generalized tonic convulsion occurred which then progressed into decorticate posture. His GCS is 3/15 (E1V1M1) and the pupils are 2.5 mm in orthophoria with sluggish reaction to light. In 34 h after hospitalization, the conditions continued to deteriorate with dilated and fixed pupils. Death occurred at day 4 after hospitalization.

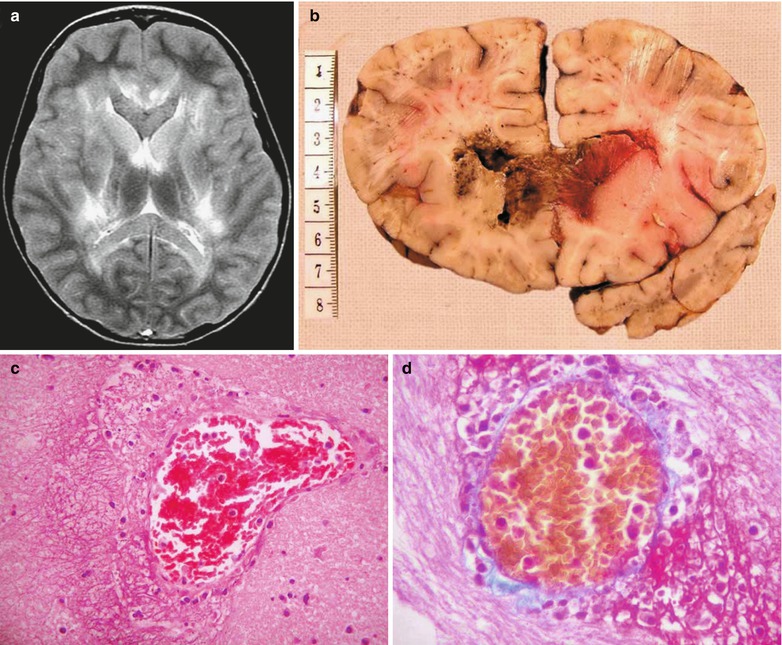

Fig. 22.5

Influenza A (H1N1) complicated by acute necrotizing encephalopathy. (a) MR imaging demonstrates bilateral symmetric abnormalities and abnormal high T2WI signal in the deep white matter of the cerebral hemisphere, caudate nucleus, lenticular nucleus, internal capsule, lateral nucleus of the thalamus and its posterior area, corpus callosum, and tegmentum of the brainstem. (b) By autopsy, the genu of the corpus callosum, mammillary body, and splenium of the corpus callosum are demonstrated from sagittal perspectives. The pathological changes include diffuse cerebral edema, vascular lesions, and necrosis, without obvious perivascular demyelination. In the necrotic area, the necrotic cells are demonstrated with illusive shadows. In the background of rare cells and swollen nerve fiber network, karyopyknosis or fragments of karyolysis and erythrocytic exudation can be found, with no astrocytes and hyperplasic microglia. Ischemic atrophy and pericellular edema are found in many neurons in the cortex of the cerebrum, hippocampus, cerebellum, and brainstem. Thrombosis is found in some minor blood vessels of the brainstem. Diffuse ischemic change of neurons and thrombosis in the brainstem and cerebellar pyramid are pathological changes secondary to cerebral edema. (c) There is a 110 μmm blood vessel in the head of the left caudate nucleus. In addition, exudation of lymphocytes and neutrophils as well as karyolysis with/without accompanying intraluminal thrombosis can be found in the vascular wall with FVL and perivascular space. (d) Martius scarlet blue staining demonstrates fibrin reservoir in the blood vessels (Note: The case and images are from Ng WF, et al. Brain Pathol. 2010;20(1):261)

22.7.2 Influenza A (H1N1)-Related Respiratory Complications

22.7.2.1 Pediatric Influenza A (H1N1) Complicated by Pneumonia

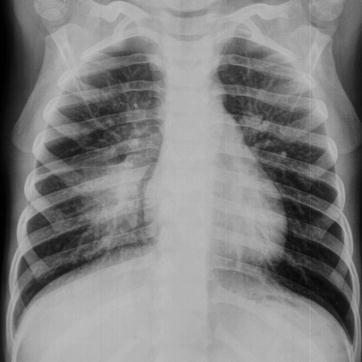

Pediatric influenza A (H1N1) complicated by pneumonia has no characteristic chest radiological demonstrations and dynamic changes in its early stage, with no obvious differences from common lung infections. In the progressing stage, parenchymal lesions are more common, possibly with complications of ARDS and mediastinal emphysema. And in the absorption stage, pulmonary interstitial lesions are more common, with blurry pulmonary markings, poor transparency of bilateral lungs, and heterogeneous lung inflation.

X-Ray

Pulmonary Parenchymal Lesions

Pulmonary parenchymal lesions are characterized by infiltrative shadows of pulmonary parenchyma that are commonly bilateral. Some studies demonstrated more common unilateral involvement than bilateral involvement, with more commonly found involvement of the right lung. The lesions are mainly located in the inner middle zone, with possible involvement of upper, middle, and lower lung fields. The involvement of middle and lower lung fields is more common. However, some scholarly studies demonstrated more commonly found lesions in the basilar part of the lungs. Parenchymal infiltration may be characterized by single or multiple small patches of shadows, which can fuse into large flakes of shadows and/or ground-glass opacity (GGO) (Figs. 22.6, 22.7, 22.8, and 22.9). In children, the lesions are commonly demonstrated as patches of shadows, while in infants and young children, the lesions are commonly demonstrated as cotton-wool opacity.

Pulmonary Interstitial Lesions

Pulmonary interstitial lesions are characterized by increased, thickened, and blurry pulmonary vascular markings, with grids shaped and nodular shadow of different degrees (Fig. 22.10). Some scholars put forward that in the early stage, X-ray of children demonstrates no interstitial changes, which might be related to the limitations of X-ray and the course of illness.

X-Ray of Severe Cases

In the severe cases, there are also demonstrations of increased pulmonary markings and excessive inflation. The causes may be the involved major airway due to perivascular lesions of the bronchi. The following necrosis of the bronchial wall and the infiltration of neutrophils cause obstruction of the small airway, leading to excessive alveolar inflation.

Others

In some cases, there are also demonstrations of involvement of the pleura, pleural effusion, mediastinal lymphadenectasis, and hilar lymphadenectasis.

Case Study 6

A boy aged 3 years complained of fever and wheezing for 6 days. He also suffered from cough, expectoration, and wheezing after physical activities. Shuanghuanglian mixture was given for 1 day, with following exacerbation of the above symptoms and accompanying dyspnea. At day 6 after the onset, pharyngeal swab was positive. It was reported that several children experienced fever in the kindergarten the boy went. By physical examination, T 39 °C, bpm 118/min, and tonsillar enlargement in first degree was found. The respiration sound of both lungs was rough, with fine moist rales in the left lower lung and large quantity wheezing sound in the right lung. Pharyngeal swab by CDC demonstrated positive M gene of influenza A (H1N1) virus, positive NP gene of swine influenza virus, and positive HA gene of influenza A (H1N1) virus. By routine blood test, WBC 9.73 × 109 /L, GR% 30.64 %, and LY% 31.14 %. By blood biochemistry, AST 42 U/L, ALT 21 U/L, and LDH 274 U/L.

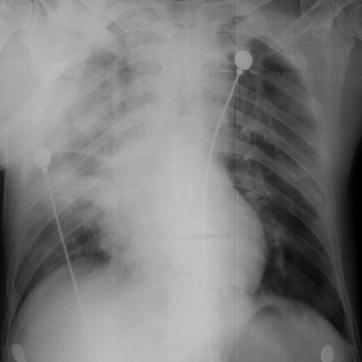

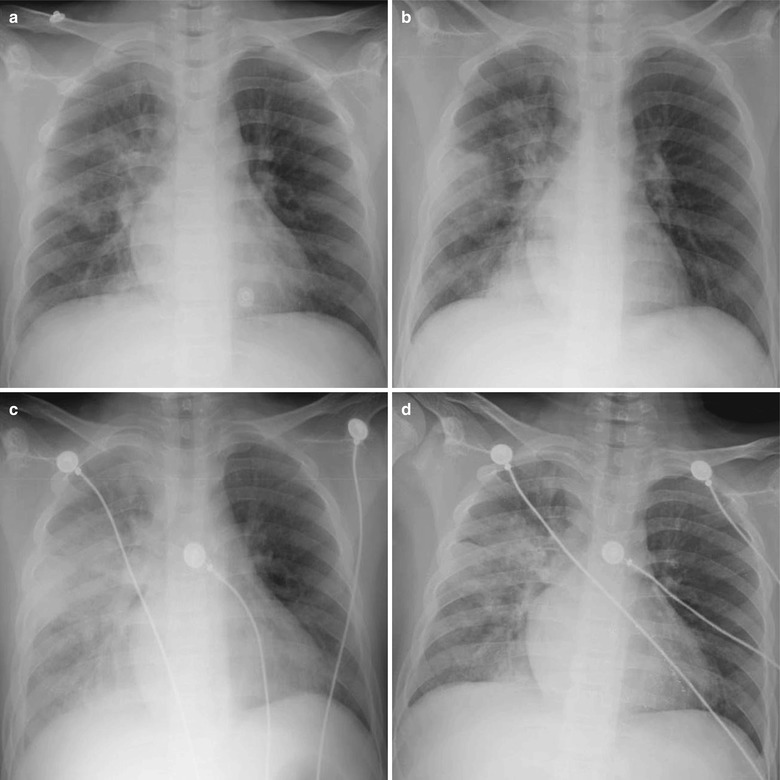

Fig. 22.6

Influenza A (H1N1) complicated by pneumonia. X-ray demonstrates increased and thickened pulmonary markings in both lungs, a large flake of high-density blurry shadow in the right lower lung, as well as enlarged and densely colored hilum

Case Study 7

A foreigner girl aged 12 years complained of fever and cough for 2 days. She also complained of accompanying chills, aversion to cold, and pharyngalgia. She had a history of contact to patients with influenza A (H1N1). By physical examination, T 38.7 °C and tonsillar enlargement in first degree was found. Pharyngeal swab by CDC demonstrated positive M gene of influenza A (H1N1) virus, positive NP gene of swine influenza virus, and positive HA gene of influenza A (H1N1) virus. By routine blood test, WBC 5.7 × 109 /L, GR% 42.1 %, and LY% 40.3 %.

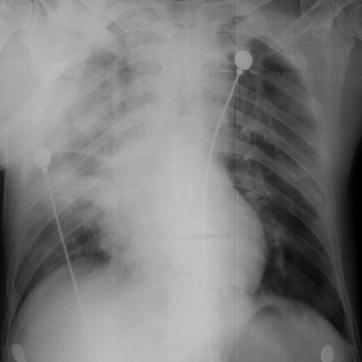

Fig. 22.7

Influenza A (H1N1) complicated by pneumonia. X-ray demonstrates a large flake of high-density blurry shadow in the right upper lung, cloudy shadow in the right middle and upper lung, as well as enlarged and blurry hilum

Case Study 8

A boy aged 10 years complained of fever for 3 days. He also complained of mild cough with no sputum, vomiting, no chills, and no fatigue. By physical examination, T 39 °C, the pharynx was congested, and tonsillar enlargement in first degree was found. He had a history of contact to patients with influenza A (H1N1). Pharyngeal swab demonstrated positive M gene of influenza A (H1N1) virus, positive NP gene of swine influenza virus, and positive HA gene of influenza A (H1N1) virus. By routine blood test, WBC 13.39 × 109 /L and GR% 84.1 %.

Fig. 22.8

Influenza A (H1N1) complicated by pneumonia. (a) X-ray demonstrates diffuse cotton-woollike shadows in both lungs, decreased transparency of lung fields, and blurry structure of both hili. (b) By reexamination after treatment for 1 day, X-ray demonstrates a rapid progress of the conditions, with cloudy high-density shadows in both lung fields. (c) By reexamination after treatment for 5 days, X-ray demonstrates a progress of the conditions, with diffuse small spots of shadows in both lungs and decreased transparency of lung fields. (d) By reexamination after treatment for 7 days, X-ray demonstrates no obvious changes. (e) By reexamination after treatment for 10 days, X-ray demonstrates improved conditions, with lesion absorption, increased pulmonary markings in both lungs, and blurry pulmonary markings in the right lower lung. (f) By reexamination after treatment for 17 days, X-ray demonstrates no obvious abnormalities in the septum between the heart and lung

Case Study 9

A boy aged 12 years complained of cough and expectoration for 2 weeks that progresses with accompanying fever for 3 days. He also complained of fatigue, poor appetite, rhinorrhea, and muscular soreness and pain. By physical examinations, T 39.8 °C, the pharynx was congested, and no tonsillar enlargement was present. He had a history of contact to patients with influenza A (H1N1). Pharyngeal swab by CDC demonstrated positive M gene of influenza A (H1N1) virus, positive NP gene of swine influenza virus, and positive HA gene of influenza A (H1N1) virus. By routine blood test, WBC 3.8 × 109 /L, GR% 23.4 %, and LY% 54.1 %. By blood gas analysis, pH 7.46, PCO2 26 mmHg, and PO2 56.9 mmHg.

Fig. 22.9

Influenza A (H1N1) complicated by pneumonia. (a) By examination at day 1 after hospitalization, X-ray demonstrates multiple flakes of blurry shadows in the right lung as well as enlarged and densely colored hilar shadow. (b) By reexamination at day 2 after hospitalization, X-ray demonstrates a progress of the conditions, with right pulmonary consolidation. (c) By reexamination at day 6 after hospitalization, X-ray demonstrates lesions with increased density and enlarged range in the right lung as well as diffuse cloudy shadows with increased density in the left lung. (d) By reexamination at day 9 after hospitalization, X-ray demonstrates improved conditions, with lesions absorbed and patches of shadows in the right lung

Case Study 10

A girl aged 2 years complained of fever, cough, and rhinorrhea for 1 day and a small quantity of tasteless thin whitish sputum. By physical examination, T 39 °C, with no clearly defined route of infection. Pharyngeal swab by CDC demonstrated positive M gene of influenza A (H1N1) virus, positive NP gene of swine influenza virus, and negative HA gene of influenza A (H1N1) virus. By routine blood test, WBC 11.2 × 109 /L, GR% 23.8 %, and LY% 65.4 %.

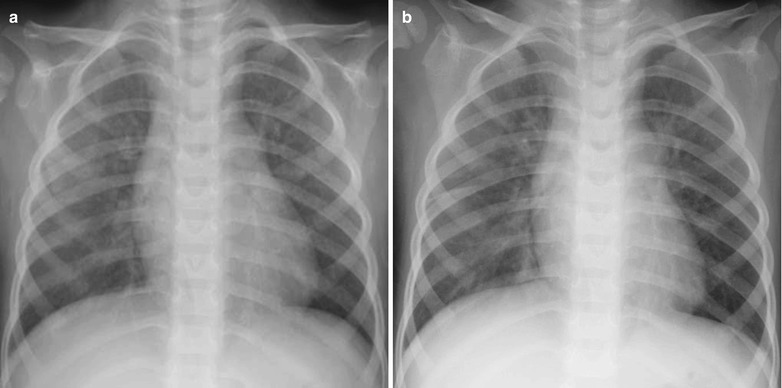

Fig. 22.10

Influenza A (H1N1) complicated by pneumonia. (a) X-ray demonstrates enhanced bilateral pulmonary markings, spots of blurry shadows in bilateral lung fields, as well as enlarged and densely colored hili. (b) By reexamination after treatment for 6 days, X-ray demonstrates clearly defined bilateral pulmonary markings and no abnormal density shadows in both lungs

CT Scanning

Demonstrations of CT scanning are basically the same as those by chest X-ray, including increased, thickened, and blurry pulmonary markings and small flakes of parenchymal shadows distributing along the bronchial tree in the lungs. Sometimes, the small flakes of parenchymal shadows may be large flakes of consolidations, with ground-glass opacity around the lesions. In addition, heterogeneous inflation and spots of interstitial changes can be found (Figs. 22.11, 22.12, and 22.13). In the severe pediatric cases, excessive pulmonary inflation may be found. CT scanning has advantages in clearly defining diseased pulmonary segments and lobes, slight pleural reaction, and small quantities of pleural effusion.

Case Study 11

A boy aged 2.5 years complained of fever and cough for 8 days. He received medications of cephalosporin antibiotics and Shuanghuanglian mixture for 2 days, with no improvement and with poor appetite, exacerbated cough, depression, and perleche. Pharyngeal swab was positive at day 9 after the onset. He had an unclearly defined history of contact to patients with influenza A (H1N1). By physical examinations, T 38.7 °C, bpm 13/min, and perleche and scattering white spots were found in the oral mucosa. He had rough breathing sound in both lungs and a large quantity of moist rales in both lungs. Pharyngeal swab by CDC demonstrated positive M gene of influenza A (H1N1) virus, positive NP gene of swine influenza virus, and positive HA gene of influenza A (H1N1) virus. By routine blood test, WBC 1.5 × 109 /L, GR% 47.34 %, and LY% 41.3 %. By blood biochemistry, ALT 32 U/L, AST 143 U/L, CK 301 U/L, and LDH 629 U/L.

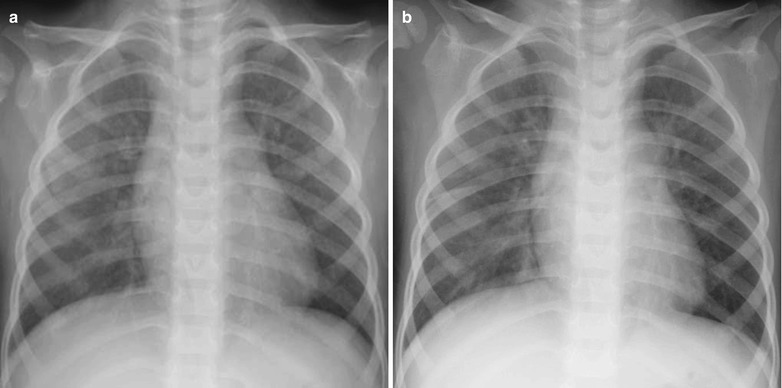

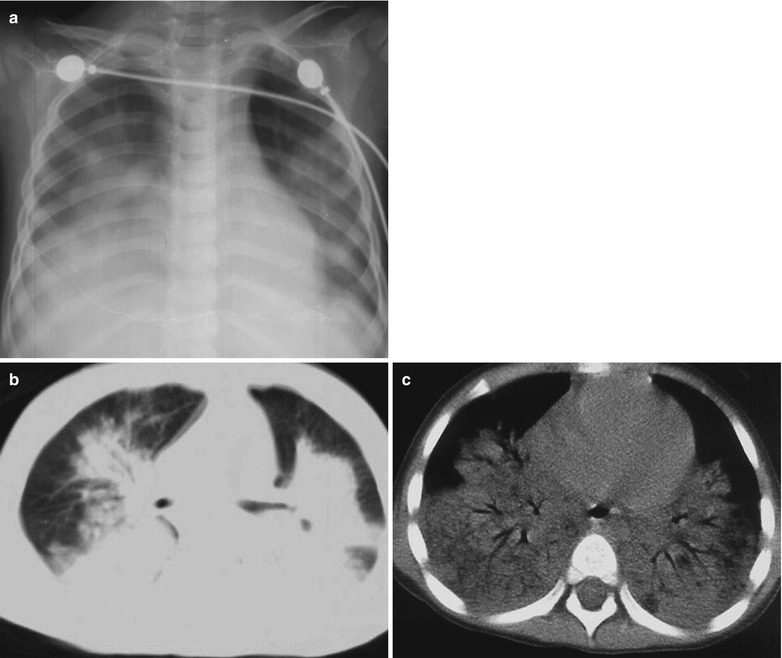

Fig. 22.11

Influenza A (H1N1) complicated by pneumonia. (a) X-ray demonstrates flakes of blurry shadow in both lungs as well as increased and thickened pulmonary markings. (b, c) CT scanning demonstrates large flake of consolidation in both lungs with air bronchus sign

Case Study 12

A boy aged 12 years complained of fever and cough for 5 days with whitish phlegm and a body temperature of 39.7 °C. After anti-infection therapy for 4 days, his conditions failed to improve, with a body temperature above 39 °C. Pharyngeal swab at day 5 after the onset was positive. By physical examination, tonsillar enlargement in first degree was found and rough breathing sound was heard in both lungs. He had a history of close contact to patients with influenza A (H1N1). Pharyngeal swab by CDC demonstrated positive M gene of influenza A (H1N1) virus, positive NP gene of swine influenza virus, and positive HA gene of influenza A (H1N1) virus. By routine blood test, WBC 3.47 × 109/L, GR% 24.72 %, and LY% 63.41 %. By blood biochemistry, ALP 400 U/L.

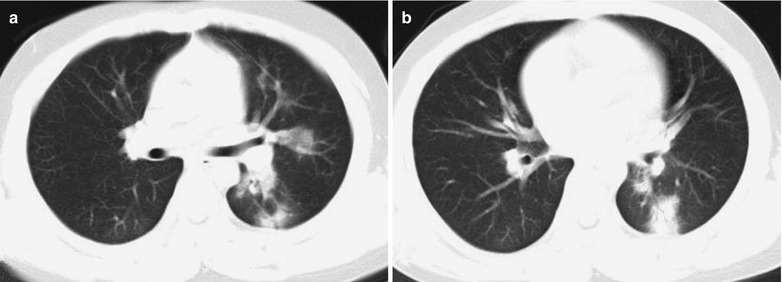

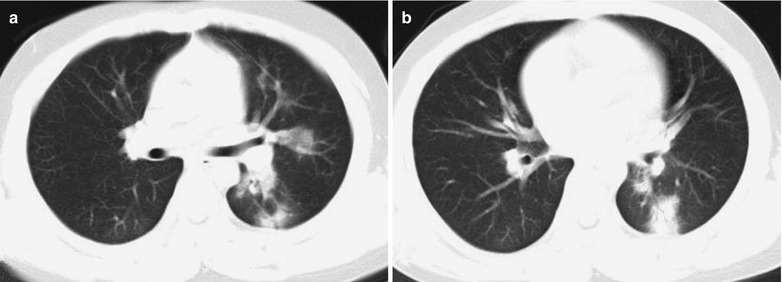

Fig. 22.12

Influenza A (H1N1) complicated by pneumonia. (a, b) CT scanning demonstrates multiple patches of shadows in the superior lingular segment of the left upper lobe and in the dorsal segment of the left lower lobe, with unclearly defined boundaries

Case Study 13

A boy aged 15 years complained of fever for 4 days as well as cough, shortness of breath, and dyspnea for 3 days. He also complained of dizziness, pharyngalgia, nasal obstruction, rhinorrhea, and cough with yellowish thick sputum difficult to expectorate. By physical examination, T 39.3 °C and grayish complexion caused by acute disease with moderate anemia, exhaustion, normal consciousness, tachypnea, pale conjunctiva, and dry lips with no cyanochroia were observed. He also had symptoms of congested pharynx, decreased breath sounds in the right lower lung, and a large quantity of fine moist rales in both middle and lower lungs that are more obvious in the right lung. He had a history of contact to patients with influenza A (H1N1). Pharyngeal swab demonstrated positive M gene of influenza A (H1N1) virus, positive NP gene of swine influenza virus, and positive HA gene of influenza A (H1N1) virus. By routine blood test, WBC 27.33 × 109/L, GR% 80.7 %, and HGB 92 g/L. By blood gas analysis, PCO2 34 mmHg, PO2 48 mmHg, SPO2 85 %, and Na 132.2 mmol/L. By myocardial enzyme analysis, CK 259 U/L, HBDH 283 U/L, LDH 283 U/L, and CK-MB 26 U/L. By blood biochemistry, AST 81 U/L, ALT 27 U/L, TP 67.2 g/L, ALB 40 g/L, TBIL 3.9 μmol/L, BUN 4 mmol/L, Cr 54 μmol/L, UA 222 μmol/L, K 4.54 mmol/L, Na 131.4 mmol/L, Cl 97.5 mmol/L, and ESR 62 mm/h. The clinical diagnosis was (1) influenza A (H1N1) complicated by severe pneumonia, respiratory failure of type I, and infectious shock, (2) moderate anemia, (3) hypoproteinemia, (4) hemoptysis of unknown causes, and (5) mediastinal emphysema.

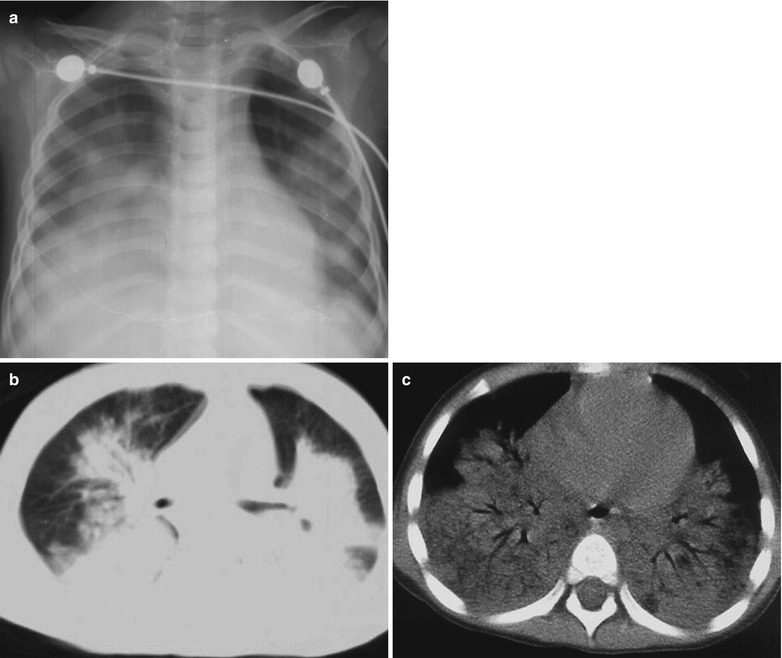

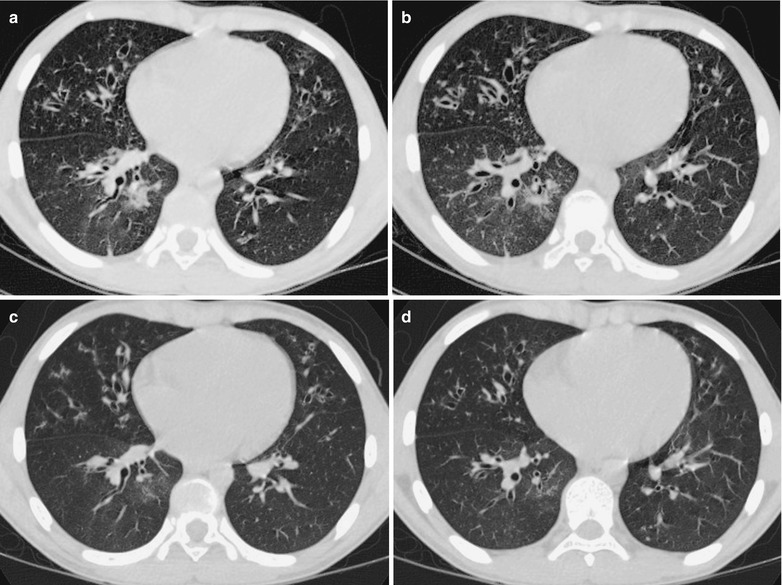

Fig. 22.13

Influenza A (H1N1) complicated by pneumonia and bronchial dilation. (a, b) CT scanning demonstrates small flake of parenchymal shadow and ground-glass opacity in the anterior lower lobe of the right lung and in the inner basal segment of the right lung, widened bronchial canals, and thickened bronchial wall of both lungs, with signet ring sign. (c, d) By reexamination after treatment for 7 days, CT scanning demonstrates the lesions improved and absorbed

22.7.2.2 Adult Influenza A (H1N1) Complicated by Pneumonia

Influenza A (H1N1) complicated by pneumonia can be primary viral pneumonia or secondary bacterial pneumonia. In the initial stage, viral pneumonia occurs, which may develop into viral and bacterial mixed pneumonia or secondary bacterial pneumonia. Mild cases are characterized by interstitial pneumonia including lesions of intrapulmonary ground-glass opacity (GGO) distributing in lobes and segments. HRCT demonstrates thickened interlobular septa in reticular appearance. Severe cases demonstrate intrapulmonary diffusive GGO that is obvious in the middle and lower lung field as well as obvious consolidation of gas cavity. HRCT demonstrations indicate interstitial changes and alveolar consolidation.

Chest X-Ray

In the early stage (the first 3 days after the onset), chest X-ray demonstrates thickened and blurry pulmonary markings and small patches of shadows, with the foci mostly located in the lower lung field and around the hilum. Due to accompanying bronchiolitis, excessive pulmonary inflation occurs. The progressing stage usually begins at day 4 after the onset, which is characterized by GGO and flakes of parenchymal shadows. The multiple scattering foci integrate rapidly and progress into extensive lesions to involve multiple segments and lobes (Figs. 22.14, 22.15, 22.16, 22.17, 22.18, and 22.19). In the convalescence stage, most of the foci are absorbed, possibly with residual cords or grid-shaped shadows and localized pulmonary emphysema. Bao et al. reported the findings of residual pulmonary giant bullae in the convalescence stage, which may be caused by excessive ventilation of local lungs due to involved terminal bronchioles by inflammation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree