Introduction to Abdomen Radiography

As an initial imaging procedure, plain film radiography of the abdomen can be useful in evaluating serious and even life-threatening conditions. Even though it may not reveal abnormalities shown by diagnostic ultrasonography and computed tomography (CT), this imaging modality can be a cost-effective method for use in diagnosing and managing abdominal pathosis. The recognition of key diagnostic features (seen incidentally on spine radiographs or noted on abdomen views used in the initial investigation of abdominal complaints) on plain film can be critical to patient management.

Limitations

A caveat to keep in mind is that the diagnostic yield of plain film of the abdomen is low in the absence of signs and symptoms; therefore, an abdomen radiograph usually is not recommended as a survey tool. Box 28-1 lists many conditions for which plain film radiographs are not indicated because roentgenographic findings rarely occur.

Indications

Common conditions for which abdominal plain films may be of value, especially if the patient presents with moderate to severe pain or if significant abdominal tenderness is present, are listed in Box 28-2. Other indications for plain film radiography of the abdomen include trauma, abdominal distension or pain, vomiting, diarrhea, and constipation (Box 28-3).

Technical Considerations

When clinically indicated, obtaining a single radiograph showing a recumbent anteroposterior (AP) view of the abdomen is the first step. Upright or decubitus views may add valuable information about gas and fluid patterns, free air, abnormal calcifications, masses, and abnormal organs. Oblique views may aid in further localizing abnormal findings. The entire abdomen should be visualized from the hemidiaphragms to the pubic symphysis. An upright, posteroanterior (PA) view of the chest may reveal valuable information about the presence of infiltrates in the lung bases, pleural fluid, or free peritoneal air that could explain the abdominal symptoms. Without the aid of contrast, abdominal contents generally are seen only if they contain gas or are surrounded by fat.

Before selecting the kilovolt peak (kVp), the patient’s size and clinical problem should be considered. Although a high peak kilovoltage is correlated with a low x-ray dose, the higher the peak kilovoltage, the less is the contrast. Often a peak kilovoltage of 80 to 90 kV is optimal, depending on what type of x-ray generator is being used (e.g., single phase, three-phase, high frequency). To minimize motion artifact, lower the exposure time and use a higher milliamperage (mA) setting.

Other Diagnostic Procedures

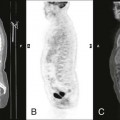

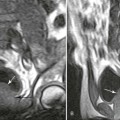

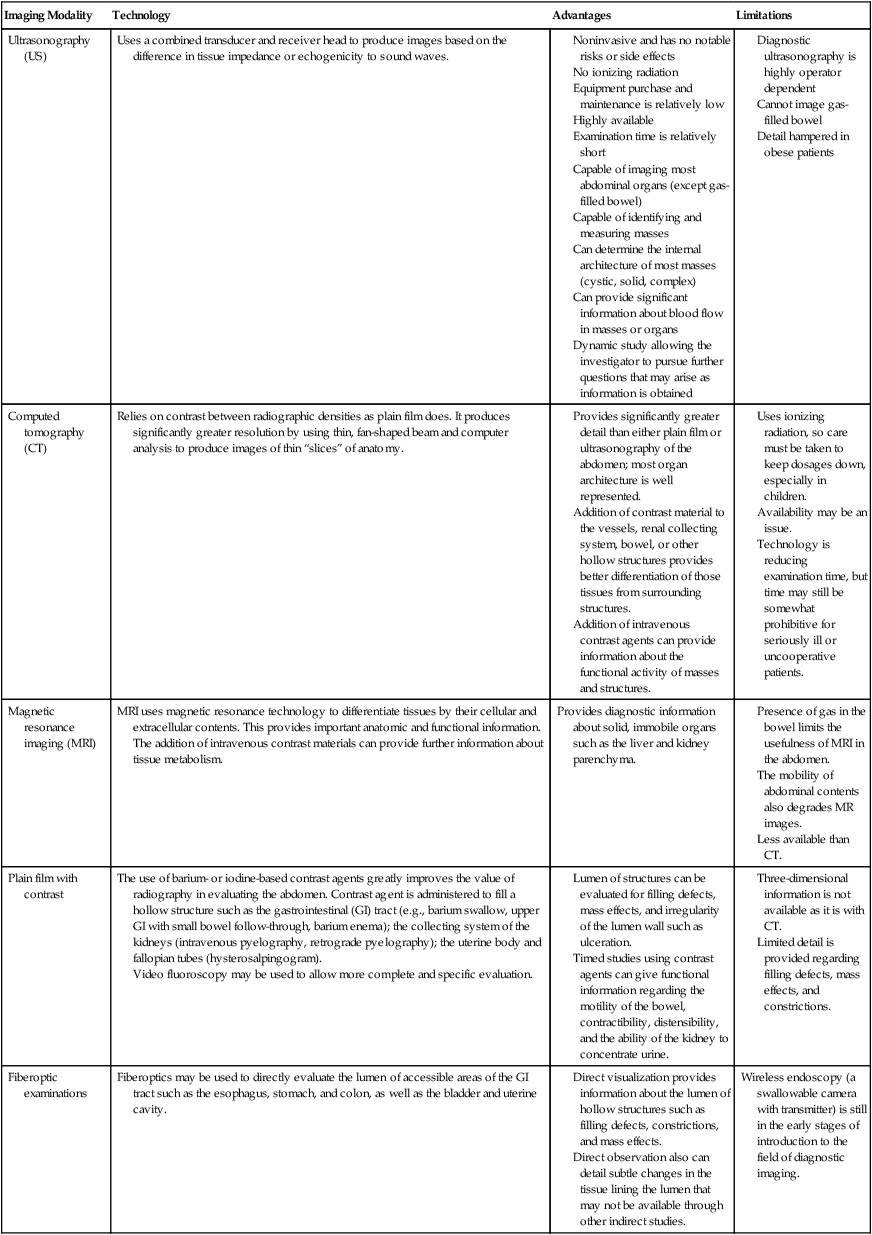

Complete evaluation of abdominal pathosis usually requires additional imaging, which may include barium-filled bowel or intravenous contrast studies, ultrasonography, CT, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), angiography, and nuclear medicine (Table 28-1). Some portions of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract can be visualized directly via fiberoptic scoping. Because the uterus is within the primary beam for abdominal imaging, pregnancy should be ruled out before conducting any imaging study that uses x-rays or radioactive material. Alternative imaging such as ultrasonography should be considered if a patient is pregnant.

TABLE 28-1

DIAGNOSTIC PROCEDURES USED FOR ABDOMINAL IMAGING

Computed tomography (CT)Relies on contrast between radiographic densities as plain film does. It produces significantly greater resolution by using thin, fan-shaped beam and computer analysis to produce images of thin “slices” of anatomy.

Provides significantly greater detail than either plain film or ultrasonography of the abdomen; most organ architecture is well represented.

Addition of contrast material to the vessels, renal collecting system, bowel, or other hollow structures provides better differentiation of those tissues from surrounding structures.

Addition of intravenous contrast agents can provide information about the functional activity of masses and structures.

Uses ionizing radiation, so care must be taken to keep dosages down, especially in children.

Technology is reducing examination time, but time may still be somewhat prohibitive for seriously ill or uncooperative patients.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)MRI uses magnetic resonance technology to differentiate tissues by their cellular and extracellular contents. This provides important anatomic and functional information. The addition of intravenous contrast materials can provide further information about tissue metabolism.Provides diagnostic information about solid, immobile organs such as the liver and kidney parenchyma.

Presence of gas in the bowel limits the usefulness of MRI in the abdomen.

Plain film with contrastThe use of barium- or iodine-based contrast agents greatly improves the value of radiography in evaluating the abdomen. Contrast agent is administered to fill a hollow structure such as the gastrointestinal (GI) tract (e.g., barium swallow, upper GI with small bowel follow-through, barium enema); the collecting system of the kidneys (intravenous pyelography, retrograde pyelography); the uterine body and fallopian tubes (hysterosalpingogram).

Video fluoroscopy may be used to allow more complete and specific evaluation.

Lumen of structures can be evaluated for filling defects, mass effects, and irregularity of the lumen wall such as ulceration.

Timed studies using contrast agents can give functional information regarding the motility of the bowel, contractibility, distensibility, and the ability of the kidney to concentrate urine.

Three-dimensional information is not available as it is with CT.

Limited detail is provided regarding filling defects, mass effects, and constrictions.

Fiberoptic examinationsFiberoptics may be used to directly evaluate the lumen of accessible areas of the GI tract such as the esophagus, stomach, and colon, as well as the bladder and uterine cavity.

Direct visualization provides information about the lumen of hollow structures such as filling defects, constrictions, and mass effects.

Direct observation also can detail subtle changes in the tissue lining the lumen that may not be available through other indirect studies.

Wireless endoscopy (a swallowable camera with transmitter) is still in the early stages of introduction to the field of diagnostic imaging.

Other Clinical Considerations

When evaluating patients with musculoskeletal pain, it is imperative that the clinician be aware that many organ diseases refer pain. The more common sites of pain referral are listed in Table 28-2.

TABLE 28-2

MUSCULOSKELETAL PAIN REFERRAL SITES ASSOCIATED WITH ORGAN DISEASE

| Diseased Organ or Disease Process | Site of Pain Referral |

| Aorta | Lumbar spine |

| Colon | Midlumbar spine |

| Gallbladder | Inferior scapula, interscapular, right shoulder |

| Gynecologic disorders | Lumbar spine; rarely above L4, pelvis |

| Kidneys, ureters | Groin, flank |

| Pancreas | Lower thoracic spine |

| Peptic ulcer | Midthoracic spine, heart area |

| Rectum | Sacral region Left lumbar paraspinal region |

| Sigmoid colon | Sacral region |

Plain Film Anatomy

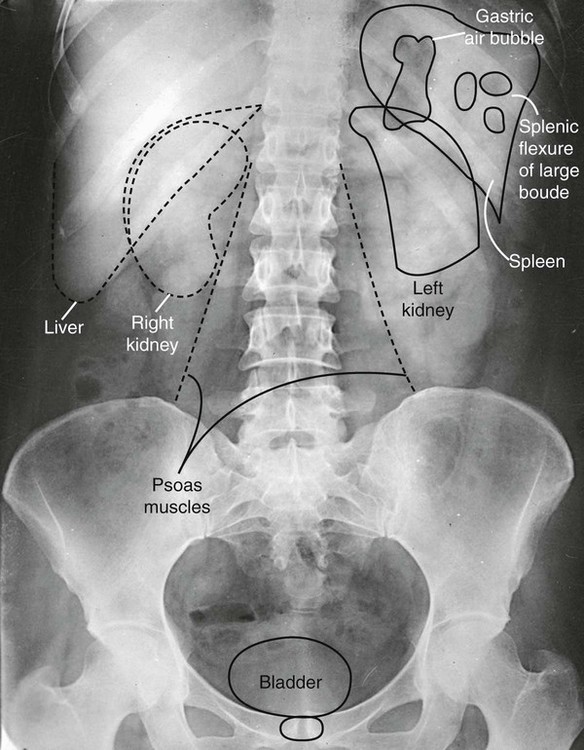

General

Interpretation of abdominal radiographs is aided by knowledge of basic anatomic relationships. The location and relative mobility of abdominal organs are important factors in the evaluation of radiographic signs (Fig. 28-1). Whether a viscus is solid or hollow also can be important. Gas in the stomach, portions of the small bowel, and most of the colon and rectum usually makes identification of these structures possible. Fat surrounding the renal capsules, along the psoas muscle edges, and abutting the inferior aspect of the liver aids in their visualization.

Retroperitoneal structures are relatively fixed in position, which increases their potential for traumatic injury, among other factors. Consistently retroperitoneal structures include the kidneys and adrenal glands, third portion of the duodenum, ascending and descending portions of the colon, psoas muscles, pancreas, and abdominal aorta. Fascial planes provide channels for the spread of fluids, cells, and pathogens. Processes affecting the psoas muscle may follow the fascial sheath as far as the lesser trochanter of the femur.

Intraperitoneal structures can be categorized by their location within conceptual quadrants of the abdomen. The liver location is fixed in the right upper quadrant (RUQ). The liver shadow generally is well outlined inferiorly by intraperitoneal fat. Basic guidelines indicate that the liver should have a homogenous density and should not extend below the level of the iliac crest (although some normal anatomic variants do this) or past the midline. The lower liver margin may be delineated by gas in the adjacent small and large bowel. Although the gallbladder almost always is in the RUQ, closely opposed to the anteroinferior aspect of the liver, it is mobile in some patients and may be found in any quadrant. Much of the ascending colon is found in the RUQ. The transverse colon is mobile, and its position may vary greatly, from running crosswise in the upper abdomen to dipping well into the pelvic area.

Interpretation

Essential to interpretation of diagnostic images is a thorough search pattern administered by skilled physicians. Imperative to detection of abnormalities, a logical, systematic manner in interpretation is needed. Whether evaluating abdominal radiographs or lumbar spinal radiographs, being cognizant of the normal appearance of key abdominal structures is vital. The ABCDs method of interpretation is a helpful systematic approach to aid clinicians in remembering which abdominal key structures to evaluate. Table 28-3 further describes the ABCDs acronym and this helpful systematic approach in evaluation the AP view of the abdomen.

TABLE 28-3

ABCDS APPROACH TO INTERPRETATION OF ABDOMINAL RADIOGRAPHS

| Acronym ABCDs | Structures to Evaluate | Comments |

| A = Abdominal layer | On abdominal radiographs, the innermost fat layer, the properitoneal fat, should be discernible. The abdominal wall’s muscles (external oblique, internal oblique, and transverse) with interspersed low-density fat may occasionally be discernible. | The properitoneal fat outlines the peritoneum in the flanks. Obliteration of the flank shadow, for example, may be caused by peritonitis or wall edema. Appendiceal abscess, for example, can alter the appearance of the adjacent properitoneal fat. |

| B = Bowel gas pattern (normal and abnormal) B = Bony structures |

Bowel gas pattern: The pattern of air-filled bowel, the bowel caliber and the most distal point of gas, typically the rectum, should be evaluated. Typically the small bowel caliber is <3 cm, and the large bowel caliber is <5 cm. Bony structures: The ribs, spine, pelvic, and hips should be evaluated, especially in the presence of trauma. |

Normally, there is no gas or a small amount of small bowel gas seen with the exception of elderly patients, patients in pain, patients with labored respiration, and children. The large intestine often has a speckled appearance because of a mixture of gas and fecal material. If the transverse colon measures >6 cm or the cecum measures >9 cm, there is an increased risk of perforation. |

| C = Calcification (normal and abnormal) | It is not uncommon to see rib calcification, which should not be confused with calcification of the gallbladder, kidneys, pancreas, adrenal glands, or other significant calcification. Evaluating vascular calcification and possible aneurysm, especially of the abdominal aorta, common iliac, and splenic arteries, is critical. |

Abdominal aortic aneurysms typically are detected as incidental findings on imaging studies performed for other purposes. Review Chapter 32 discussing pathologic processes in the abdomen that may cause soft-tissue calcifications. |

| D = Diaphragm | Note the position of the diaphragm and look for possible free air under one hemidiaphragm or the other. | Free air within the abdomen, pneumoperitoneum, can be secondary to recent laparoscopic surgery. The most common pathologic cause is perforation of gastric or duodenal ulcer. |

| S = Soft tissues of pelvis S = Sulcus of lung S = Sizes and locations of key abdominal organs |

Soft tissues of the pelvis: Look for the bladder shadow. In women, the uterus, which lies immediately above the bladder, can deform the bladder shadow. Sulcus of the lung: Evaluate the visible lung tissue for infiltrate or lung nodules that may be better demonstrated on abdominal films that include the diaphragm. Sizes and locations of key abdominal organs: Direct signs of abdominal masses are visualizing the actual mass or an alteration in the size, contour, or density of an abdominal or pelvic organ or identifying gas, fat, or calcium in the mass. The indirect signs are displacement of normal structures and obliteration of normal fat lines of the organ. Evaluate for displacement of mobile structures (stomach, transverse colon and sigmoid colon, small bowel, urinary) that can be pushed by an enlarging mass. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree