Cancer staging is how clinicians describe the state of the disease, predict prognosis, help determine best treatment, and interpret outcomes. Although several staging systems are available, the most widely used is the tumor node metastasis (TNM) system developed by the American Joint Committee on Cancer. Knowledge of normal anatomy and the myriad appearances of variations in anatomy is the basis of accurate tumor staging. Cross-sectional imaging is complementary to the clinical examination for accurate staging.

Key points

- •

Cancer staging is how clinicians describe the state of the disease, predict prognosis, help determine best treatment, and interpret outcomes.

- •

Although several staging systems are available, the most widely used is the tumor node metastasis (TNM) system developed by the American Joint Committee on Cancer.

- •

Knowledge of normal anatomy and the myriad appearances of variations in anatomy is the basis of accurate tumor staging.

- •

Cross-sectional imaging is complementary to the clinical examination for accurate staging.

The tumor node metastasis staging system

Cancer staging is the common language by which clinicians describe the state of the disease, predict prognosis, help determine best treatment, and interpret outcomes. Although there are several staging systems available, the most widely used is the tumor node metastasis (TNM) system developed by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) in collaboration with the International Union for Cancer Control (UICC). The first AJCC staging manual was published in 1977, and because the manual is revised every 6 to 8 years, the AJCC seventh edition published in 2010 (AJCC7) is the current version. The manual is available as a 650-page book, a small handbook, and on CD-ROM. The AJCC manual is organized by body part, and head and neck is the first anatomic area covered.

The TNM system categorizes each patient’s disease based on location, size, and extent of the primary tumor (T), location, number and extent of nodal metastases (N), and presence of distant metastases (M). Thus, the basis is anatomic. Factors that affect prognosis such as human papillomavirus (HPV) 16 status, the smoking or drinking history, or comorbidities are important, but have not yet been incorporated into the staging system.

Tumors can be staged at various points through the treatment cycle. Specifically, clinical stage is at presentation before treatment, pathologic stage is after surgery, and posttherapy stage is after first course of nonoperative therapy, whether radiation, systemic, or both. The initial clinical stage remains the most significant factor to determine prognosis and additional therapy, and is the stage used in reporting survival statistics. The initial clinical stage often appears in every clinical and follow-up report. Thus, even years later and even if a patient is free of disease, clinical notes list the patient as a TNM stage.

Despite the nearly universal use of the TNM staging system and the widespread availability of AJCC manuals in both written and electronic versions, in our experience, diagnostic radiologists rarely include the anatomic stage of the primary tumor in the formal written imaging interpretation. That listing the stage in the dictation is the exception rather than the rule is puzzling. Because the AJCC staging system is anatomic, with the exception of mucosal or skin lesions, the best opportunity to accurately stage the patient is by interpretation of the modern imaging. Even endoscopic biopsies are limited in determining deep extent of head and neck cancer. Why, then, do even subspecialty-trained radiologists hesitate to commit to an anatomic stage in each of their dictations?

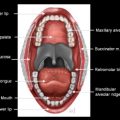

The answer, as with any significant medical question, is multifactorial, and likely is related to lack of knowledge regarding normal anatomy, patterns of tumor appearance and spread, and important locations of tumor extension that would change clinical staging. Normal head and neck anatomy is complicated, with small structures present in compact regions. The presence of some structures, such as cranial nerves, can be appreciated only by knowing normal anatomy, because they are so small as to evade visualization with current imaging equipment. Tumor resection and subsequent reconstruction to restore normal function and obtain adequate cosmetic result make follow-up imaging even more difficult.

In the past, the radiologist has had to rely on a frequently illegible blurb of a history on an imaging request form. With the advent of the electronic medical record, the radiologist has access to the clinical signs and symptoms to help their review of the imaging. For example, a history of pain along cranial nerve V2 distribution prompts a second look at that relevant anatomy.

Knowledge of normal anatomy and the myriad appearances of variations in anatomy is the basis of accurate tumor staging. Comprehensive review of head and neck anatomy is not the goal of this issue of Clinics . Instead, our goal is to show how the AJCC manual can be a guide to interpreting computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance (MR) imaging of the patient with head and neck cancer. Only with a thoughtful interpretation and dictation, clearly delineating the local extent of a primary head and neck tumor, can the radiologist offer a precise description of a tumor following guidelines of AJCC, giving value to the referring clinician, tumor board members, and the patient.

Consider the patient presenting with a mass in the tonsil. The referring clinician is likely aware of the mass, so a final dictation just confirming the mass is of little value. Frequently in our head and neck tumor board (HNTB), we see outside dictations that say “Impression: Large tonsillar mass, correlate clinically, tumor cannot be excluded.” Questions that remain include size (“large” is vague and of little use when following the patient), whether there is extension to the base of tongue, soft palate, or pterygoids (all of which may affect whether the patient goes for surgery or the target volumes for the radiation oncologist) and does tumor approach, invade, or surround the internal carotid artery (a finding of tremendous prognostic significance that has direct bearing on the operability of the lesion, particularly in the era of transoral resections)? The interpretation offers little guidance for staging, and therefore no direction for treatment plan or prognosis for the patient. Is the patient a surgical candidate? Are radiation and chemotherapy more appropriate for treatment? Is the tumor curable? What is the prognosis? These pertinent questions arise in the HNTB, and the imaging interpretation is critical to answering the questions that the clinicians should be asking. In turn, a multidisciplinary HNTB significantly affects patient care, and the opportunity to actively participate in the HNTB should not be missed.

Table 1 is current staging for cancer of the oropharynx from AJCC7. Because the tonsil is a subsite of the oropharynx, Table 1 should be used by the radiologist to offer a clinical stage based on imaging. Instead of reporting a large tumor, notice that gradations of size that affect tonsillar cancer stage are 2 cm or smaller ( Fig. 1 ), more than 2 to less than 4 cm ( Fig. 2 ), or greater than 4 cm. Report the actual tumor size as opposed to only the T stage.

| Primary Tumor (T) | |

|---|---|

| TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed |

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumor |

| Tis | Carcinoma in situ |

| T1 | Tumor ≤2 cm in greatest dimension |

| T2 | Tumor >2 cm but not >4 cm in greatest dimension |

| T3 | Tumor >4 cm in greatest dimension or extension to the lingual surface of epiglottis |

| T4a | Moderately advanced local disease Tumor invades the larynx, extrinsic muscle of tongue, medial pterygoid, hard palate, or mandible a |

| T4b | Very advanced local disease. Tumor invades lateral pterygoid muscle, pterygoid plates, lateral nasopharynx, or skull base or encases carotid artery |

a Mucosal extension to lingual surface of epiglottis from primary tumors of the base of the tongue and vallecula does not constitute invasion of larynx.

Note that T1 and T2 are based exclusively on size. For T3 stage, size is important, greater than 4 cm, but presence of tumor on the epiglottis is important. More precisely, extension to the mucosal surface facing the oropharynx (the lingual surface) is another critical observation ( Fig. 3 ). Therefore, both size and extension to the lingual epiglottic surface should be mentioned.

For all head and neck subsites, the T4 staging is now divided into “moderately advanced,” or “very advanced” local disease. T4 tumors by definition have extended out of the boundaries of that subsite and involve surrounding sites. For staging a T4a oropharyngeal tumor, the radiologist must be able to identify the supraglottic larynx, extrinsic tongue muscles (the hyoglossus, styloglossus, genioglossus, and mylohyoid muscles), medial pterygoid muscle, hard palate, and mandible, because extension to 1 or more of those sites infers the T4a stage ( Fig. 4 ). T4b or “very advanced local disease” means that an oropharyngeal tumor has invaded the lateral pterygoid muscle or pterygoid plates, the lateral nasopharynx, skull base, or is circumferential around the internal carotid artery.

Because of its detail, the AJCC staging manual is a wonderful guide for cross-sectional image interpretation, and facilitates generating a useful, value-added CT or MR dictation for a patient with cancer of the tonsil. Overall, using the AJCC manual guides the radiologist in making the most useful interpretations of the imaging.

The tumor node metastasis staging system

Cancer staging is the common language by which clinicians describe the state of the disease, predict prognosis, help determine best treatment, and interpret outcomes. Although there are several staging systems available, the most widely used is the tumor node metastasis (TNM) system developed by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) in collaboration with the International Union for Cancer Control (UICC). The first AJCC staging manual was published in 1977, and because the manual is revised every 6 to 8 years, the AJCC seventh edition published in 2010 (AJCC7) is the current version. The manual is available as a 650-page book, a small handbook, and on CD-ROM. The AJCC manual is organized by body part, and head and neck is the first anatomic area covered.

The TNM system categorizes each patient’s disease based on location, size, and extent of the primary tumor (T), location, number and extent of nodal metastases (N), and presence of distant metastases (M). Thus, the basis is anatomic. Factors that affect prognosis such as human papillomavirus (HPV) 16 status, the smoking or drinking history, or comorbidities are important, but have not yet been incorporated into the staging system.

Tumors can be staged at various points through the treatment cycle. Specifically, clinical stage is at presentation before treatment, pathologic stage is after surgery, and posttherapy stage is after first course of nonoperative therapy, whether radiation, systemic, or both. The initial clinical stage remains the most significant factor to determine prognosis and additional therapy, and is the stage used in reporting survival statistics. The initial clinical stage often appears in every clinical and follow-up report. Thus, even years later and even if a patient is free of disease, clinical notes list the patient as a TNM stage.

Despite the nearly universal use of the TNM staging system and the widespread availability of AJCC manuals in both written and electronic versions, in our experience, diagnostic radiologists rarely include the anatomic stage of the primary tumor in the formal written imaging interpretation. That listing the stage in the dictation is the exception rather than the rule is puzzling. Because the AJCC staging system is anatomic, with the exception of mucosal or skin lesions, the best opportunity to accurately stage the patient is by interpretation of the modern imaging. Even endoscopic biopsies are limited in determining deep extent of head and neck cancer. Why, then, do even subspecialty-trained radiologists hesitate to commit to an anatomic stage in each of their dictations?

The answer, as with any significant medical question, is multifactorial, and likely is related to lack of knowledge regarding normal anatomy, patterns of tumor appearance and spread, and important locations of tumor extension that would change clinical staging. Normal head and neck anatomy is complicated, with small structures present in compact regions. The presence of some structures, such as cranial nerves, can be appreciated only by knowing normal anatomy, because they are so small as to evade visualization with current imaging equipment. Tumor resection and subsequent reconstruction to restore normal function and obtain adequate cosmetic result make follow-up imaging even more difficult.

In the past, the radiologist has had to rely on a frequently illegible blurb of a history on an imaging request form. With the advent of the electronic medical record, the radiologist has access to the clinical signs and symptoms to help their review of the imaging. For example, a history of pain along cranial nerve V2 distribution prompts a second look at that relevant anatomy.

Knowledge of normal anatomy and the myriad appearances of variations in anatomy is the basis of accurate tumor staging. Comprehensive review of head and neck anatomy is not the goal of this issue of Clinics . Instead, our goal is to show how the AJCC manual can be a guide to interpreting computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance (MR) imaging of the patient with head and neck cancer. Only with a thoughtful interpretation and dictation, clearly delineating the local extent of a primary head and neck tumor, can the radiologist offer a precise description of a tumor following guidelines of AJCC, giving value to the referring clinician, tumor board members, and the patient.

Consider the patient presenting with a mass in the tonsil. The referring clinician is likely aware of the mass, so a final dictation just confirming the mass is of little value. Frequently in our head and neck tumor board (HNTB), we see outside dictations that say “Impression: Large tonsillar mass, correlate clinically, tumor cannot be excluded.” Questions that remain include size (“large” is vague and of little use when following the patient), whether there is extension to the base of tongue, soft palate, or pterygoids (all of which may affect whether the patient goes for surgery or the target volumes for the radiation oncologist) and does tumor approach, invade, or surround the internal carotid artery (a finding of tremendous prognostic significance that has direct bearing on the operability of the lesion, particularly in the era of transoral resections)? The interpretation offers little guidance for staging, and therefore no direction for treatment plan or prognosis for the patient. Is the patient a surgical candidate? Are radiation and chemotherapy more appropriate for treatment? Is the tumor curable? What is the prognosis? These pertinent questions arise in the HNTB, and the imaging interpretation is critical to answering the questions that the clinicians should be asking. In turn, a multidisciplinary HNTB significantly affects patient care, and the opportunity to actively participate in the HNTB should not be missed.

Table 1 is current staging for cancer of the oropharynx from AJCC7. Because the tonsil is a subsite of the oropharynx, Table 1 should be used by the radiologist to offer a clinical stage based on imaging. Instead of reporting a large tumor, notice that gradations of size that affect tonsillar cancer stage are 2 cm or smaller ( Fig. 1 ), more than 2 to less than 4 cm ( Fig. 2 ), or greater than 4 cm. Report the actual tumor size as opposed to only the T stage.